Chronic Low Back Pain

Original Editors - Bryan Jacobson, Tori Westcott, Ashley Bohanan, Alisha Lopez

Lead Authors -

Description/Description[edit | edit source]

Low back pain (LBP) is the fifth most common reason for physician visits, which affects nearly 60-80% of people throughout their lifetime. Low back pain that has been present for longer than three months is considered chronic, although there is still no consensus about the definition of CLBP. Specific causes of LBP are uncommon, and in approximately 90% of patients a specific generator cannot be identified with certainty.[1] More than 80% of all health care costs can be attributed to chronic LBP. Nearly a third of people seeking treatment for low back pain will have persistent moderate pain for one year after an acute episode. It is estimated that seven million adults in the United States have activity limitations as a result of chronic low back pain[2]

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) has been associated with neurochemical, structural, and functional cortical changes[3] of several brain regions including the somatosensory cortex.[4] Complex processes of peripheral and central sensitisation may influence the evolution of acute to chronic pain.[5]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The lumbar region is situated under the thoracic region of the spine. The lower back consists of five vertebrae (L1- L5). It has a slight inward curve known as lordosis. The fifth lumbar vertebrae is connected with the top of the sacrum. The vertebrae of the lumbar spine are connected in the back by facet joints, which allow for forward and backward extension, as well as twisting movements.The two lowest segments in the lumbar spine, L5-S1 and L4-L5, carry the most weight and have the most movement, this makes the area prone to injury. In between vertebrae are spinal discs, they provide support. Discs in the lumbar region of the spine are most likely to herniate or degenerate, which can cause pain in the lower back, or radiating pain to the legs and feet. The spinal cord travels from the base of the skull to the joint at T12-L1, where the thoracic spine meets the lumbar spine. At this segment, nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord, forming the cauda equina. Some lower back conditions may compress these nerve roots, resulting in pain that radiates to the lower extremities, known as radiculopathy. The lower back region also contains large muscles that support the back and allow for movement in the trunk of the body. These muscles can spasm or become strained, which is a common cause of lower back pain. (Prometheus)

Epidemiology /Aetiology[edit | edit source]

5-10% of all low back pain patients will develop CLBP. CLBP prevalence rates are lower in individuals aged 20-30 years, increasing from the third decade of life, and reaching the highest prevalence between 50-60 years. However the prevalence rates stabilise in the seventh decade of life. There’s no difference in CLBP prevalence at different periods of the year or in different places.[6]

There is higher CLBP prevalence in females, people of lower economic status, people with less schooling and smokers. There’s indication that prevalence has doubled over time. This may be due to important changes in lifestyle (obesity) and in the work industry. Factors as a family history of disabling back pain, radiating pain, advice to rest upon back pain consultation, occupational LBP or LBP caused by traffic injury are all associated with chronic disabling back pain over lifetime.[7] Job satisfaction and psychosocial factors also play a role in the development of CLBP.[8]

Musculoskeletal disorders are a comorbid condition strongly linked to CLBP. A moderate association was found when considering the whole musculoskeletal chapter, a stronger association was found when considering the somatoform symptoms related to the musculoskeletal cluster.[9]

In patients with low back pain (LBP), alterations in fiber typing in Multifidus and erector spinae are assumed to be possible factors in the etiology and/or recurrence of pain symptoms as it negatively affects muscle strength and endurance. In case of the latter, type I fibers have been argued to be more affected by pain and immobilization than type II fibers.[10]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Most patients that suffer from CLBP experience pain in the lower area of the back (lumbar and sacroiliac regions) and mobility impairment. Pain can also radiate in the lower extremities, or generalized pain can be present. Patients with CLBP can also experience movement and coordination impairments. This could affect the control of voluntary movements of the patient.

It can be challenging for the patient to maintain the neutral position, malalignment of the body can occur. It can also be found difficult to maintain a standing, sitting or a lying position, especially in case of radiating pain to the lower extremities. Carrying things in the arms, or bending can also provoke complaints. Daily activities, such as cleaning, sports and other recreational occupations can become a big task for people with CLBP.

When pain is generalized, sensory experiences of the patient can also become altered; fear-avoidance beliefs, pain catastrophizing and depressive thoughts can appear.[11] If symptoms like these occur, Central sensitisation can be present. It is important to monitor these Yellow Flags, as well as it is important to monitor blue flags and black flags.

The complaints are recurring and occur longer than three months. It is possible that CLBP passes in episodes. Some episodes are more severe than others, but overall the patient is affected by the impairments. Eventually, social contact and work environment will suffer from this great impact on the patient's health and wellbeing.

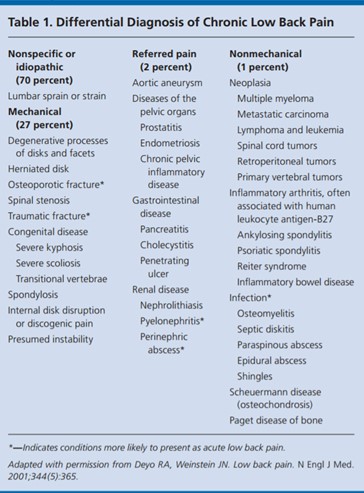

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Lower back pain is a frequent condition for patients seeking care from physical therapists in outpatient settings. The challenge for clinicians is to recognize patients in whom lower back pain may be related to underlying pathological conditions.

Table 1 gives a list of differential diagnosis.[12]

For back pain associated with specific spinal cause, such as radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT (computed tomography) may establish diagnosis.[12]

In some differential diagnosis, immediate intervention is required.

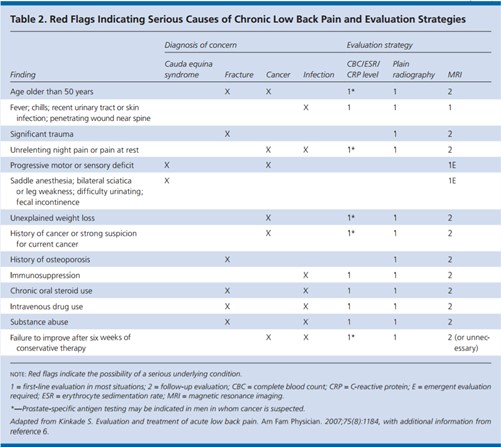

Table 2 shows a list of “red flags”: Red flags in spinal conditions, specific for lower back pain. These are signs or indicators of possible (severe) underlying pathology.[12] When these signs are present, further screening is required and patients should be referred on as indicated. NICE clinical guidelines issued in 2016 and the KCE report 2017 suggest that red flags relating to thoracic pain, night pain and being aged over 50, that are used to screen for cancer, have limited diagnostic accuracy and they recommend using clusters of red flags and clinical expertise to guide decision making and referral to a specialist[13][14]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Chronic lower back pain is difficult to diagnose on one hand, but on the other hand the definition is very simple. In fact, if the back pain continues to be present for 3 months or more, we can consider it “chronic lower back pain”. Generally, patients are diagnosed based on their history. The specific diagnosis is then formulated based on the examination and clinical outcomes. Questionnaires can be used such as the STarT Back, Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire or the PICKUP[15], as well as a body pain diagram, on which the patient locates his pain and pain distribution.[16]

In case of specific lower back pain, other diagnostic procedures are required to confirm diagnosis. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT-scan) may put these diseases forward (radiculopathy, discopathy …). Nevertheless, patients are frequently misdiagnosed. Normal age-related degenerative changes in the spine can be misinterpreted as an initiator of pain, although we can see the same changes in people with no complaints. For this reason, radiological pictures differ according to age, even in patients with no chronic low back pain[17][18][19].

It is also important to check for any presence of red flags.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Validated self-report questionnaires, such as the Oswestry Disability Index and the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire should be used at baseline and throughout the course of treatment to monitor a change in a patient’s status.[11] The Modified Somatic Perceptions Questionnaire (MSPQ) is used to assess pain intensity, disability and somatic pain perception respectively.The MSPQ is relevant and appropriate for use in a CLBP study as it was devised and evaluated specifically for CLBP and an MSPQ score > 13 is one of the clinical predictors of lumbar facet syndrome.[12]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Research has shown that the patient history and biopsychosocial evaluation are crucial to establish chronic LBP. Patient history and self-report forms help rule out serious pathologies such as cauda equina, Ankylosing Spondylitis, nerve compromise and cancer. The Fear‐Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ) self-report form has been shown to predict chronicity and psychosocial factors influencing patient prognosis[20] The focus of the physical examination is to confirm the hypothesis of chronic LBP by eliminating other pathologies or mechanisms[21]

There are also clinical tests that could be used to sort patients with a higher risk for CLBP from patients with (sub)acute low back pain. The best predictor is the lumbar spine flexion test. Other differences might be seen in functional tests, sensation in the feet, and in the different pain provocation tests.[22]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Identifying risk factors allows development of healthcare strategies (and prevention) to reduce the burden of chronic pain. Some risk factors cannot be changed, but others can be modified. Risk factors include socio-demographic, clinical, psychological and biological factors. For example anxiety, depression and catastrophizing beliefs (yellow flags) are associated with chronic pain and with a poor prognosis.[23]

Operant treatment approaches can be integrated into standard pain management for acute/subacute low back pain. Graded activity and behavioural education are promising treatment approaches for the prevention of CLBP and explaining the physiology of pain can also work preventive.[24][11]

Medical management[edit | edit source]

Pharmacology: Recent clinical guidelines on the management of chronic low back pain from United Kingdom[13], Belgium[14] and United States[25] have recommended changes to the use of pharmacotherapy when treating chronic low back pain. Where non-pharmacological interventions have not been successful medication should only be prescribed at the lowest doses for the shortest amount of time.[15] However it’s important to advise patients of the known potential harms and benefits. Pharmacotherapy should only be used as a tool to stay active and to engage in treatment, rather than as a solution itself.

- Acetaminophen: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is an antipyretic and analgesic medication without anti-inflammatory properties. Risk of hepatotoxicity is the main complication.[2] All three recent guidelines[13][14][25] recommend that acetaminophen should no longer be used for acute (high quality evidence) or chronic episodes (low quality evidence) of LBP. A Cochrane systematic review found that acetaminophen was no more effective than a placebo when treating acute LBP and its efficacy on chronic LBP is uncertain[26].

Recent research states that there are a lot of uncertainties about the effect of paracetamol so there is a need for further research. There is only low-quality evidence for no effect on immediate pain reduction.[26] - NSAIDS: Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory drugs are pain relieving and anti-inflammatory medications that block the cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 enzyme. Side-effects include gastrointestinal and renal complications, such as bleeding ulcers and perforation. NSAIDS are slightly effective for the improvement of disability.[2][27] The use of NSAIDs are recommended by three of the recent guidelines but in low doses and where the risk of developing side effects are low.[13][14][25].

- Opioids: Opioids in the past were used for patients who experienced moderate or severe pain. There has been a change in their recommended use and all recent guidelines advise that opioids should be used with caution because of the risk for potential harm of addiction and accidental overdose. However, the recommendations for their use and how they are prescribed differ between the guidelines. Research has found opioids moderately effective for pain relief, although effects on functional outcomes were small and should only be prescribed where the benefits outweigh the risks[26]. Slow-release opioids are recommended when compared to immediate-release opioids to prevent adverse effects, and should be given regularly rather than as needed. Due to the addictive nature of opioids, long-term use should be carefully monitored for misuse.[2][28]

- NICE, the UK guidelines,[13] no longer recommends opioids for chronic low back pain

- KCE, the Belgian guidelines, [14] recommends opioids for chronic low back pain but advises against regular use

- American College of Physician's guidelines, recommends opioids as a last resort for treating chronic low back pain for people who have not responsded to non-pharmacological interventions and where other pharmacological options have failed.

- Antidepressants: Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) are commonly used to treat numerous chronic pain syndromes. However, there is conflicting evidence on whether there are significant changes in pain relief or disability with CLBP. A recent systematic review found that there is evidence of moderate quality indicating that there is no difference in pain relief between antidepressants and placebo for patients with chronic LBP.[29] The NICE clinical guidelines[13] do not suggest ricyclic antidepressants and non-selective serotonin-norepinephrin reuptake inhibitors . Whereas the KCE guidelines found both to have a potential benefit for chronic pain with central sensitisation (eg. increased activity of the central nervous system). Depression is common in patients with chronic low back pain and should be treated appropriately[21]

- Other medications: Skeletal muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, and antiepileptic medications are not recommended because of the insufficient evidence towards their effectiveness for chronic low back pain.[2]

Multidisciplinary approach

When treating patients with chronic LBP it has been shown that having been treated by a multidisciplinary team yields improvements. The multidisciplinary approach includes treating the physical, psychological, emotional, and socio professional aspects of the disorder[30]"Fear of pain in turn is supposed to initiate worrying about the consequences of pain and hence increases avoidance behavior, leading in the long term to increased pain, functional disability, and depression."[31]

In patients who have already failed a course of conservative treatment, multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes result in better outcomes with respect to long term pain and disability compared with usual care or physical treatments. Patients in these programmes also have increased odds of being at work compared with patients receiving physical treatment.[32]

For more information: Behavioral pain management of chronic low back pain

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

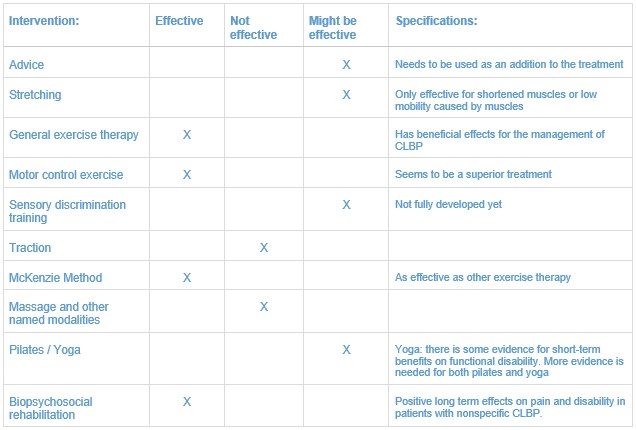

Interventions:

- Advice: For nonspecific low back pain the general advice on self-management is to remain active. This is also the case in CLBP.[11][21] (resource - guideline based on level 1a and level 1b evidence)

It is frequently assumed that a firm mattress has beneficial effects on low back pain. In fact, for patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain (with no referred pain), a medium-firm mattress is found to be superior. Patients experience less pain and disability during the day and overnight.[33]

Giving advice only will probably not suffice. It is important to combine multiple treatment means to avoid recurrency.[11] - Stretching and flexibility exercises: are used to improve hamstring, quadriceps, piriformis, and hip joint capsule range of motion.[34] The aim is to reduce pain, improve movement, and improve functional limitations of movement.

Exercise therapy[edit | edit source]

Exercise therapy has been shown to have beneficial effects for the management of chronic low back pain and is recommended in all three recently published clinical guidelines[13][14][25].[35] Utilization of trunk coordination, strengthening, and endurance exercises reduces low back pain and disability in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain with movement coordination impairments.[11] Moderate- to high-intensity exercise will be considered for patients with CLBP without generalized pain. For patients with CLBP with generalized pain incorporating progressive, low-intensity, submaximal fitness and endurance activities into the pain management and health promotion strategies will be considered.[11]

- Core strengthening exercises: are used to restore the coordination and control of the trunk muscles to improve control of the lumbar spine and pelvis. These exercises aim to restore the strength and endurance of the trunk muscles to meet the demands of control. Core exercise may be more effective than general exercise in relieving pain and improving back-specific function for patients with CLBP in the short term. No significant differences were found in the long term.[36]

- Motor control exercise: motor control exercise protocols have been shown to be an effective treatment of chronic low back pain. Common targeted muscles include transversus abdominis, multifidus, the diaphragm and pelvic floor muscles.The focus of motor control exercises is to improve neuromuscular control of trunk segments involved in movement of the spine.[37][38][39][40] Motor control exercises seem to be superior to several other treatments, such as general exercise (with regard to disability in the short-, intermediate, and long-term and pain in the short- and intermediate term), spinal manual therapy (with regard to disability during all time periods) and minimal intervention (during all time periods with regard to pain and disability)[41]

Instructions: An independent contraction of the deep stabilizing muscles, such as the transversus abdominis and multifidus, facilitated by pelvic floor contraction, which leads to their co-contraction, whilst instructing to control breathing by maintaining resting tidal volumes throughout deep trunk activation maneuvers. Progression is achieved when mastery of contraction in static tasks is achieved. Then move on to implementation of deep muscle contraction during dynamic tasks. Daily practice at home for 30 minutes is instructed.[35]

- Sensory discrimination training: cortical reorganization presents a barrier to successful recovery; however the plasticity that underpins cortical reorganization also suggests that it might be responsive to targeted treatments, such as sensory discrimination training (SDT). SDT comprises tactile discrimination and sensorimotor retraining approaches, which involve the recognition of the location and the type of the stimuli by the patient (localization training). However, these approaches are not fully developed from a pathoanatomical perspective, since the processes involved in cortical reorganization in CLBP are not fully understood .[42]

- Traction: Summary evidence concludes that mechanical lumbar traction is not effective for treating acute or chronic nonspecific low back pain (LBP) Few trials evaluated the effectiveness of treatments for radicular low back pain, but the available evidence showed traction and spinal manipulation were not effective or were associated with small effects.[43]

- Mckenzie Method: Has been shown to be as effective as other exercise therapy. Compared to motor control exercises there is no significant difference in pain and function scores. However patients reported greater improvement in sense of recovery in the short term compared to patients who received motor control exercises. This obviously might differ across different groups of patients.[35]

- Massage is now recommended in both the acute and chronic stages of back pain[15] but modalities such as electrical nerve stimulation, low-level laser therapy, shortwave diathermy and ultrasonography have not been shown to be effective interventions.[15][21] Exercise focusing on general improvement of strength and cardiovascular endurance is not suggested for optimal outcomes in patients with chronic low back pain.[39]

- Acupunture is no longer support by the UK and Belgian guidelines but is still supported by the American guidelines but they state that the improvement in pain symptoms may be small.[25]

Pilates:[edit | edit source]

There is inconsistent evidence that pilates is effective in reducing pain and disability in people with CLBP, with a lack of long term follow up information.[44] A randomised control trial from 2015 investigated pilates to improve pain (VAS), function and quality of life (SF-36) for people with chronic lower back pain.[45] 60 patients were split into either the experimental group (EG) who continued their medication while completing pilates or the control group (CG) which only continued their medication. Other outcome measures included function (Roland Morris questionnaire), satisfaction (Likert scale), flexibility (sit and reach) and NSAID intake which were assessed at baseline and after 45, 90 and 180 days. Results concluded that groups at baseline were homogenous. There was statistical difference in favour of the EG with reduction of pain (P < 0.001), function (P < 0.001) and the quality of life domains of function capacity (P < 0.046). Statistical difference was also found between groups regarding the use of pain medication at 45, 90 and 180 days (P < 0.010), with the EG taking fewer NSAIDs than the CG.

Following this a 2015 Cochrane review was completed investigating pilates for LBP. It included research up until March 2014 with 10 studies and 510 patients with CLBP[46]. Duration of treatment ranged from 10 to 90 days, follow up ranged from 4 weeks to 6 weeks and sample size ranged from 17 to 87 participants. It concluded that pilates is probably more effective than minimal intervention in the short and intermediate term for pain and disability and more effective than minimal intervention for improvement in function and global impression of recovery in the short term. However, pilates is probably not more effective than other exercises for pain and disability at short and intermediate term. For function, other exercises were more effective at intermediate term but not at short term follow up. Therefore there couldn’t be a conclusion for pilates on LBP.

Also, in 2015 a systematic review was completed investigating the effect of pilates exercise programs in patients with CLBP [47]. There were 29 eligible articles up until July 2014 used. Six articles investigated pilates versus other exercise, nine investigated pilates versus no treatment or minimal intervention for short term pain, five investigated the therapeutic effect of pilates in randomised cohort and nine analysed reviews. The systematic review concluded that there were a lack of studies demonstrating the efficacy of pilates over other treatments for chronic pain. However, pilates is more effective then minimal physical exercise interventions in reducing pain.

PRESCRIPTION OF PILATES: In 2018 a randomised control trial investigated different doses of pilates in 296 patients with non-specific CLBP [48]. Patients were allocated into four groups; booklet group (BG), pilates once per week (PG1), pilates twice per week (PG2), pilates three times per week (PG3). Outcome measures included pain and disability at six week follow ups. Results concluded that PG1 had significant improvements compared to BG and that the PG2 had significant improvements compared to PG1.

These studies from the last five years conclude that pilates is beneficial to people with CLBP. The evidence found an improvement in outcomes when comparing pilates to minimal intervention, but no significant improvement compared to other exercise. When doses are increased from once a week to twice a week pain and disability are reduced, especially in the short term with no adverse effects noted in the literature. Therefore, pilates should be considered as a safe adjunct alongside other exercises for patients with CLBP. NHS Choices suggests that regular pilates practice can help improve posture, muscle tone, balance and joint mobility, as well as relieve stress and tension. They have endorsed an instructive pilates video for patients with CLBP. It explains warm ups, safely getting on and off the floor and progressions to each move with reps and sets explained. Information can be found at: https://www.nhs.uk/video/Pages/pilates-for-chronic-back-pain.aspx

Yoga:[edit | edit source]

Evidence in recent years has suggested yoga to be an efficacious adjunctive treatment for chronic low back pain [49]. A systematic review showed there to be moderate certainty evidence that yoga is superior to non-exercise interventions (Education booklets) at improving back function at 6 months; low evidence that this continued onto 12 months. The study also investigated back focused exercise versus yoga and those interventions combined versus back focused exercise alone. Evidence was of low certainty and showed little to no difference between the interventions for both the outcome of back function and pain [50].

A further systematic review published in 2017 reported lower pain scores (P<0.001) and improved function (P<0.01) at 24 weeks following a programme of lyengar yoga compared with a control group receiving usual care[51]. When compared with exercise, similar results were reported however effect sizes were small and differences were not always statistically significant. Lower short-term pain intensity was also associated with yoga when compared to education (0.45; CI 0.63 to 0.26), however the effects were smaller and not statistically significant at long term follow-up.

A randomised noninferiority trial from 2017 compared yoga and physiotherapy against each-other in addition to a comparison of each against education.[52] A 12-week yoga programme was shown to produce equivalent results to the physiotherapy intervention (1.7 reduction in Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) v 2.3 reduction). The difference fell within the pre-set inferiority margin of 1.5 points. The results of the study differed from previous literature when considering short term outcomes of yoga versus education, where it was shown to be inferior to education for both pain reduction and function. However, following a maintenance phase (either booster yoga sessions or home exercise programme), functional outcomes such as a reduction in pain medication were superior for the yoga group compared to education.

PRESCRIPTION OF YOGA: Specific details regarding the prescription of yoga are poorly reported in the literature [53]. With regards to the length of the class, 75 minutes was referred to in several studies [54],[52]). The breakdown of this time varies between studies with the time dedicated to warm up and yoga postures ranging from 40 minutes[54] through to 55 minutes [52]. Saper et al. (2013), compared once versus twice-weekly yoga classes for CLBP, suggesting there was no statistically significant difference for pain reduction or back-related function between the increase in frequency of classes.

Details of specific yoga postures and warm up exercises were given in both studies [52][54]with some examples shown in the below figures. Supplementary material was also published alongside the 2017 study including a participant booklet [55]and a yoga instructors manual.[56]

To conclude yoga has had a positive impact on pain and function outcomes in patients with CLBP. It has been found to have a statistically significant difference compared to minimal intervention however results comparing to exercise and usual physiotherapy are inconsistent. Yoga should be considered as an adjunct to usual physiotherapy until further higher quality studies have been produced.

Biopsychosocial rehabilitation (cognitive behavioural therapy)[edit | edit source]

For patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain, more specifically patients who have already had full conservative treatment, a biopsychosocial rehabilitation program might result in positive long term effects on pain and disability. [32] For more information see: CBT approach to Chronic Low Back Pain

Also pain education and graded exercise therapy could play an important role. There has not been found a significant difference between the effect of motor control exercises and graded exercise therapy, but subgroups of patients might respond better to one of these interventions.[37]

Resources[edit | edit source]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBh4_7YtLaA

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

A multidisciplinary approach in treating chronic low back pain is advised. Especially in patients who have already failed a course of conservative treatment, multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes result in better outcomes with respect to long term pain and disability compared with usual care or physical treatments. Physical therapy should consist of exercise therapy (and no manual therapy). The exercise therapy might be general exercise therapy, the Mckenzie method, or motor control exercises. Pilates and yoga could be used if the patient has interest in this. Biopsychosocial rehabilitation is advised in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain, education and graded exercise could also play an important role for these patients. Above all, it’s important to choose a therapy that fits the individual patient.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ I. Khan, R. Hargunani et al. “The lumbar high-intensity zone: 20 years on.” Clinical Radiology, 6 June 2014, 551-558

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Chou R. Pharmacological Management of Low Back Pain. Drugs [online]. 2010;70 (4):387-402. (level of evidence 2c)

- ↑ Aure OF, Nilsen JH, Vasseljen O. Manual Therapy and Exercise Therapy in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized, Controlled Trial With 1-Year Follow-Up. Spine. 2003;28(6):525-532.

- ↑ S. Kälin, A.K Rausch-Osthoff et al. “What is the effect of sensory discrimination training on chronic low back pain? A systematic review.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2016. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ R. Izzo et al. “Spinal pain.” European Journal of Radiology, 2015, 746-756

- ↑ Meucci, Rodrigo Dalke, Anaclaudia Gastal Fassa, and Neice Muller Xavier Faria. "Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review." Revista de saude publica 49 (2015).

- ↑ Fujii, Tomoko, and Ko Matsudaira. "Prevalence of low back pain and factors associated with chronic disabling back pain in Japan." European Spine Journal 22.2 (2013): 432-438.

- ↑ Patrick, Nathan, Eric Emanski, and Mark A. Knaub. "Acute and chronic low back pain." Medical Clinics of North America 100.1 (2016): 169-181.

- ↑ Ramond-Roquin, Aline, et al. "Psychosocial, musculoskeletal and somatoform comorbidity in patients with chronic low back pain: original results from the Dutch Transition Project." Family practice (2015): cmv027.

- ↑ R. Izzo et al. “Spinal pain.” European Journal of Radiology, 2015, 746-756

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Anthony Delitto. et al., “Low Back Pain Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):A1-A57. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.0301 (resource - guideline based on level 1a and level 1b evidence)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Last, Allen R., and Karen Hulbert. "Chronic low back pain: evaluation and management." American family physician 79.12 (2009): 1067-74.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG59]. London: NICE, 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Van Wambeke P, Desomer A, Ailliet L, et al. Summary: Low back pain and radicular pain: assessment and management. KCE report 287Cs. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2017. https://kce. fgov.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/KCE_287C_Low_ back_pain_Summary.pdf

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Almeda Matheus, Saragiotto B, Richards B, Maher C. Primary care management of non-specific low back pain: key messages from recent clinical guidelines. MJA 2018. 208:6 272-275

- ↑ Southerst, D., et al., “The reliability of body pain diagrams in the quantitative measurement of pain distribution and location in patients with musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review”, Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 2013, Volume 36, Number 7, p. 450-459.

- ↑ P. Barelli et al. “The dark side of facet joint.” Medical Suisse. 2016.

- ↑ .S. Kälin, A.K Rausch-Osthoff et al. “What is the effect of sensory discrimination training on chronic low back pain? A systematic review.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2016. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Panta O.B., et al., “Morphological Changes in Degenerative Disc Disease on Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Comparison Between Young and Elderly.” Nepal health Resource council, 2015, (31): 209 - 13.

- ↑ George S, Fritz J, Bialosky J, et al. The effect of a Fear-Avoidance-Based Physical Therapy Intervention for Patients With Acute Low Back Pain: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trail. Spine. [online]. 2003; 28(23): 2551-2560.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross TJ, Shekelle P, Owens DK. Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478-491. (resource – guideline based on level 1a and level 1b evidence)

- ↑ Paatelma, M., Karvonen, E., Heiskanen, J., “Clinical perspective: how do clinical test results differentiate chronic and subacute low back pain patients from “non-patients”?”, The Journal of Manual and Manipulative therapy, volume 17, number 1, 11-19.

- ↑ Van Hecke, O., Torrance, N., Smith, B.H., “Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance”, British Journal of Anaesthesia, 2013, 111 (1), 13-18.

- ↑ Brunner, E., et al., “Can cognitive behavioural therapy based strategies be integrated into physiotherapy for the prevention of chronic low back pain? A systematic review”, Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation, 2013, volume 35, issue 1, 1-10.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166: 514-530.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, et al. Paracetamol for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (6): CD012230

- ↑ Enthoven, Wendy, et al. "Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain." The Cochrane Library (2016). (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Deshpande A, Furlan AD, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk D. Opioids for chronic low back pain. The Cochrane Collaboration. [online]. 2010;3:1-34. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Kuijpers T, Middelkoop M, Rubinstein S, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for chronic non-specific low-back pain. European Spine Journal [online]. 2011;20:40-50 (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Demoulin C, Grosdent S, Vanderthommen M, et al. Effectiveness of a semi-intensive multidisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation program in chronic low back pain. Joint Bone Spine [serial online]. 2010; 77 (1): 58-63. (level of evidence 2b)

- ↑ Samwell H, Kraaimaat F, Crul B, van Dongen R, Evers A. Multidisciplinary allocation of pain treatment: long term outcome and correlates of cognitive-behavioral processes. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain [serial online]. March 2009; 17(1): 26-36. (level of evidence 4)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Kamper, S.J. et al., “Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis”, BMJ, 2015; 350:h444 (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Kovacs, Francisco M., et al. "Effect of firmness of mattress on chronic non-specific low-back pain: randomised, double-blind, controlled, multicentre trial." The Lancet 362.9396 (2003): 1599-1604. (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Gianni F. et al., “Comparison of 2 Multimodal Interventions With and Without Whole Body Vibration Therapy Plus Traction on Pain and Disability in Patients With Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain.” Journal of chiropractic Medicine, 2016, 243 - 251. (level of evidence 2b)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Mark H. Halliday et al., “A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the McKenzie Method to Motor Control Exercises in People With Chronic Low Back Pain and a Directional Preference.” J. Orthopedic Sports Physical Therapy, 2016;46(7):514-522. (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Wang, X., et al., “A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain”, PLoS One, 2012;7(12):e52082 (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Macedo LG, Maher CG, Latimer J, McAuley JH. Motor Control Exercise for Persistent, Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Physical Therapy. 2009;89:9-25. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Waterloo's Dr. Spine, Stuart McGill . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=033ogPH6NNE [last accessed 09/12/16] (resource)

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Latimer J, Herbert RD, Hodges PW, Jennings MD, Maher CG, Refshuage KM. Comparison of General Exercise, Motor Control Exercise and Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial. Pain. 2007;131:31-37. (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Costa LOP, Majer CG, Latimer J, Hodges PW, Herbert RD, Refshauge KM, McAuley JH, Jennings MD. Motor Control Exercise for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Physical Therapy. (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Byström, M.G., Rasmussen-Barr, E., Grooten, W.J.A., “Motor control exercises reduces pain and disability in chronic and recurrent low back pain: a meta-analysis”, Spine, 2013, Volume 38, Issue 6, p.350-358. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ S. Kälin, A.K Rausch-Osthoff et al. “What is the effect of sensory discrimination training on chronic low back pain? A systematic review.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2016. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Voloshin, A., and Josef Wosk. "An in vivo study of low back pain and shock absorption in the human locomotor system." Journal of biomechanics 15.1 (1982): 21-27. (level of evidence 2b)

- ↑ Wells, C., et al., “Effectiveness of pilates exercise in treating people with chronic low back pain: a systematic review of systematic reviews”, BMC medical research methodology, 2013, 13:7. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Natour, J., Cazotti, L.D.A., Ribeiro, L.H., Baptista, A.S. and Jones, A., 2015. Pilates improves pain, function and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation, 29(1), pp.59-68.

- ↑ Yamato, T.P., Maher, C.G., Saragiotto, B.T., Hancock, M.J., Ostelo, R.W., Cabral, C.M., Costa, L.C.M. and Costa, L.O., 2016. Pilates for low back pain: complete republication of a cochrane review. Spine, 41(12), pp.1013-1021.

- ↑ Patti, A., Bianco, A., Paoli, A., Messina, G., Montalto, M.A., Bellafiore, M., Battaglia, G., Iovane, A. and Palma, A., 2015. Effects of Pilates exercise programs in people with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Medicine, 94(4).

- ↑ Miyamoto, G.C., Franco, K.F.M., van Dongen, J.M., dos Santos Franco, Y.R., de Oliveira, N.T.B., Amaral, D.D.V., Branco, A.N.C., da Silva, M.L., van Tulder, M.W. and Cabral, C.M.N., 2018. Different doses of Pilates-based exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial with economic evaluation. Br J Sports Med, pp.bjsports-2017.

- ↑ Susan Holtzman and R Thomas Beggs, “Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Pain Research and Management, 2013, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 267-272. (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Wieland, L.S., Skoetz, N., Pilkington, K., Vempati, R., D'Adamo, C.R. and Berman, B.M., 2017. Yoga treatment for chronic non‐specific low back pain. The Cochrane Library.

- ↑ Chou, R., Deyo, R., Friedly, J., Skelly, A., Hashimoto, R., Weimer, M., Fu, R., Dana, T., Kraegel, P., Griffin, J. and Grusing, S., 2017. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Annals of internal medicine, 166(7), pp.493-505.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Saper, R.B., Lemaster, C., Delitto, A., Sherman, K.J., Herman, P.M., Sadikova, E., Stevans, J., Keosaian, J.E., Cerrada, C.J., Femia, A.L. and Roseen, E.J., 2017. Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: a randomized noninferiority trial. Annals of internal medicine, 167(2), pp.85-94.

- ↑ Sherman, K.J., 2012. Guidelines for developing yoga interventions for randomized trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Saper, R.B., Boah, A.R., Keosaian, J., Cerrada, C., Weinberg, J. and Sherman, K.J., 2013. Comparing once-versus twice-weekly yoga classes for chronic low back pain in predominantly low income minorities: a randomized dosing trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013

- ↑ Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Delitto A, Herman PM, Stevans J, Paris R, et al. Yoga Participant Manual. Supplement to: Yoga vs. physical therapy vs. education for chronic low back pain in predominantly minority populations: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014; 15:67. [PMID: 24568299] doi:10.1186/1745-621515-67 Accessed at https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art% 3A10.1186%2F1745-6215-15-67/Media Objects/13063_2013_1959 _MOESM1_ESM.pdf

- ↑ Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Delitto A, Herman PM, Stevans J, Paris R, et al. Yoga Teacher Training Manual. Supplement to: Yoga vs. Physical therapy vs. Education for chronic low back pain in predominantly minority populations: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014; 15:67. [PMID: 24568299] doi:10.1186/1745-621515-67 Accessed at https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art% 3A10.1186%2F1745-6215-15-67/Media Objects/13063_2013_1959 _MOESM2_ESM.pdf