Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP)

Top Contributors - Sydney Cudmore, Megan Grubb, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Caitlyn Zavitz, Amanda Ager, Tania Bhogal and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

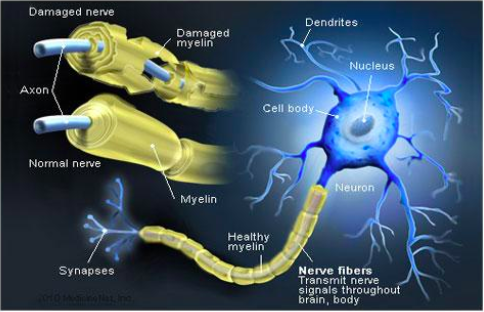

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is a progressive autoimmune disease that destroys the myelin sheaths of peripheral nerves[1][2]. Individuals with this nervous system disorder tend to present physically with symmetrical weakness, balance problems, impaired sensation and diminished reflexes in addition to problems at a neurological level[1][2]. The long term nature of this condition leads to abnormalities in gait and impairments in both psychological and social functioning[1] .

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

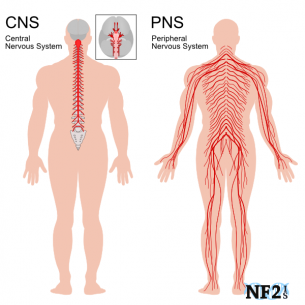

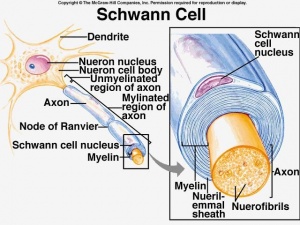

The human nervous system can be divided into 2 parts. The central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system, which contains all nerves that supply the rest of the body. Surrounding the peripheral nerves is a white, fatty layer of myelin that is made up of glial cells, termed Scwhann cells. The myelin coating generated by the Schwann cells assists the axons in transmitting faster neural impulses to receptor sites, such as organs and muscles. In CIDP this myelin is destroyed resulting in nerve conduction changes and impairments, such as limb weakness and sensory loss[6].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

CIDP can be distinguished into two categories; typical and atypical cases. Symmetric motor/sensory impairments with proximal and distal weakness and areflexia, slowed conduction rate, temporal dispersion, and/or a conduction block occurs in typical cases of CIDP. Atypical cases can present in a number of different ways. Most commonly atypical cases are purely sensory or predominantly sensory, multifocal with persistent conduction block, and cases that present with similar and bilateral distal symptoms[8]. Pathological changes have been seen to be more pronounced in the spinal nerve roots, major plexuses, and proximal nerve trunks. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies following patients for an extended period of time have concluded that nerve hypertrophy and/or *gadolinium enhancement are more prominent in these areas[9].

*Gadolinium: Is commonly used in MRI studies as the primary contrast media[10].

Immunopathology[edit | edit source]

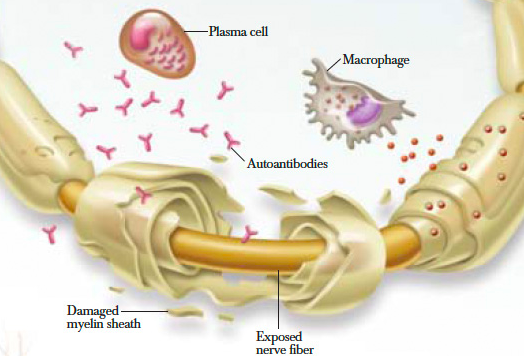

When looking at the immunopathology of CIDP the two important cells to analyze are T and B lymphocytes. They both play a primary role along with macrophage cells in myelin phagocytosis as seen within nerve lesions of CIDP. Additionally, T cells play an important role in the increased permeability of the blood nerve barrier as seen on MRI studies of inflammatory neuropathies. A high percentage of patients with CIDP have been shown to have positive outcomes to plasma exchange therapy. This suggests that the antibody or other soluble factors are pathogenic in this disease[9].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Incidence: CIDP is suspected to be vastly underestimated, in part due to underreporting, uncertainty in making the diagnosis and diagnostic criteria inconsistencies [2]. Many research studies report different distributions of cases with diagnostic numbers as low as 0.5 per 100,000 children and 1 to 2 per 100,000 adults[12] to as high as 7.7 per 100,000[2].

Gender: Although research is limited, there is a slight predilection for men[8][13]

Age: Individuals diagnosed with CIDP are generally aged 40-60, although children and elderly people may be affected[13]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Individuals often report difficulty with walking, climbing stairs, balance and manual dexterity, which is attributed to the progressive, symmetric limb weakness and sensory loss. It is commonly seen to affect proximal muscles in the early stages and then progressively move to the distal limbs. Numbing, buzzing and tingling may be characteristic of sensory loss reported by patients and neuropathic pain is less often reported[13].

On the contrary, some individuals may not present with these symptoms, which makes diagnosis much more difficult and can take many years, leaving patients with no answers and increased frustration[14].

After complete subjective and objective history in addition to further medical investigations, which may take multiple months after symptom onset, the following aspects have been recognized as major cardinal features of CIDP[15]:

- Progression over at least 2 months

- Predominant motor symptoms

- Symmetric involvement of arms and legs

- Proximal muscles involved along with distal muscles

- Deep tendon reflexes reduction or absence

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein elevation without pleocytosis

- Nerve conduction evidence of a primary demyelinating neuropathy

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnoses include:[8][12]

- Multifocal motor neuropathy

- Diabetic polyneuropathy

- Fibromyalgia

- Multiple sclerosis

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

- Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS)

- Neuropathy associated with: nutritional deficiencies, critical illness, toxins, systemic inflammatory diseases

Global muscle weakness of the upper and lower extremities, the reduction of deep tendon reflexes and aggressive course of the disease are distinguishing factors between CIDP and chronic length-dependent peripheral neuropathies[8].

The demyelinating form of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), which is a form of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), and CIDP are quite similar in nature and are differentiated by their time of progression[8]. GBS often occurs after an identifiable infectious illness, vaccination or surgery, 3-4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms. In comparison, CIDP often does not have an easily identifiable antecedent event and progresses for 8 weeks or more[8].[13].

As stated previously, CIDP is suspected to be vastly underestimated[2]. On the contrary, there is research suggesting that a misdiagnosis of CIDP commonly occurs in other neurologic conditions[16]. This misdiagnosis is attributed to the lack of implementation of specific clinically relevant criteria and electrodiagnostic criteria. One study even determined that a whopping, “Forty-seven per cent of patients referred with a diagnosis of CIDP failed to meet minimal CIDP diagnostic requirements” [16]. The amount of underreporting and misdiagnoses demonstrates the importance of implementing the most current and valid diagnostic criteria.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

It is not uncommon for CIDP to go undiagnosed for months to years depending on a patient's symptoms. This could be due to symptoms not being prominent enough to affect an individual's day to day routine and cause concern to visit their physician. In addition, the presence of non debilitating symptoms makes it difficult to give a definitive diagnosis of CIDP in the early stages, even after follow up with their physician[14]. Diagnosing CIDP depends upon the appearance of the demyelination process found during electrophysiological testing. According to a study performed by Mathey & Pollard a possible criterion method has been developed in order to determine whether an individual has CIDP by looking at the demyelination process. This process is defined by the presentation of any of the following in at least two nerves[9]:

- Prolongation of distal latency

- Reduction in motor conduction velocity

- Prolongation of F waves

- Partial conduction block

- Abnormal temporal dispersion

- Prolonged distal compound muscle action potential (CMAP) duration and one other demyelinating parameter in one other nerve

Since the pathological changes in polyradiculoneuropathies such as CIDP or GBS involve proximal regions mainly, these regions need to be examined electrophysiolgoically by testing F waves. The purpose is to look for a proximal conduction block or for recording evoked potentials, however, routine studies may sometimes be normal[9].

Features that support a diagnosis include the following[9]:

- Elevated CSF protein without an increased leukocyte count

- MRI evidence of gadolinum enhancement or nerve root plexus hypertrophy

- Nerve biopsy finding of primary demyelination

- Improvement following immunotherapy

It has also been noted that motor fibres tend to be more affected compared to sensory nerves and this is taken into consideration during the diagnosis stage[8]. Another diagnosing feature of CIDP is that it tends to affect more of the proximal muscles first, typically causing torso weakness in early stages [8].

According to the American Academy of Neurology in order to have a definitive diagnosis both a cerebrospinal fluid sample must be taken, as well as a nerve biopsy[12]. However, there is a current controversy regarding the need for the biopsy to be performed in order to be included in the diagnosis (Lewis, 2007). Other possible ways to confirm or reject a diagnose include: lab studies based on serum glucose, glycated hemoglobin, thyroid function studies, hepatitis profiles, HIV testing and serum immunofixation electrophoresis[8].

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

Most therapies used to treat CIDP aim to block immune processes in order to stop inflammation and demyelination, in addition to preventing secondary axonal degeneration. Patients who respond to treatment must continue until their condition is stabilized or maximum improvement occurs. Improvements are measured with comparable signs such as improvement in sensation, strength and the performance of activities of daily living (ADL’s). Further treatment/maintenance therapy is provided to assist the individual with the intention to reduce the frequency of relapses and slow disease progression. Patients should be aware that infections, systemic conditions and neurotoxic drugs can negatively influence the symptoms of CIDP[12]. Additionally, treatments also aim to reduce patient symptoms, such as weakness and pain, and improve overall functional status[13].

Occupational therapists can prescribe gait aids, specialized tools and ankle-foot orthotics, if necessary, to assist individuals with functional tools for ADL’s and ambulation. Psychologists may also be an important part of the interprofessional team as they can address symptoms that often accompany a diagnosis of a chronic disease and change in functional status, such as depression, anxiety or frustration[13].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Corticosteroids

- Plasma exchange

- Immunosuppressive therapy

Research by Koller et al.,2005[12] it suggests that 60 to 80 percent of patients that are treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, corticosteroids or plasma exchange have improvements in their condition, but the long-term prognosis varies according to when the therapy is initiated and the degree of associated axonal loss.

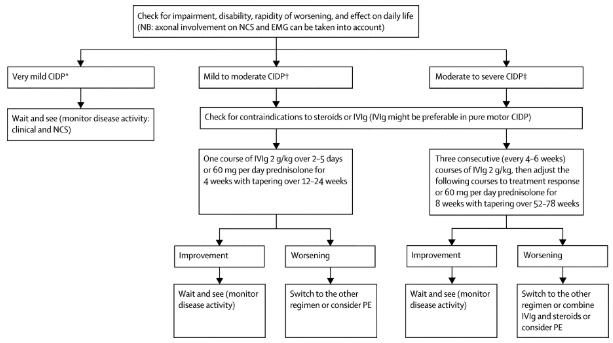

The following describes the process of choosing medical management as suggested by Vallat[18]:

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

A physiotherapist's role in the treatment of CIDP needs to be very specialized to each individual. Physiotherapists prescribe gait aids that may assist with balance and ambulation during ADL’s. Manual therapy may also be provided when indicated to prevent joint contractures and maintain available ROM. Since many individuals with CIDP have difficulty with balance and walking, gait retraining and exercise programs prove to be beneficial at increasing efficiency and endurance[13].

Exercises that promote muscle strengthening and aerobic conditioning are important once patients have received clearance from a physician for an exercise program[21]. Exercise parameters for CIDP patients also need to be individually tailored as it is important that individuals don’t over-exert themselves. As a result of the demyelination of axons the body is unable to recruit as many muscle fibres to complete a task, which may cause the muscle fibres that are engaged to be overworked. Some delayed onset muscle soreness is expected to occur, but pain that persists longer than 12-48 hours, with or without a loss of strength, is an indication that the F.I.T.T. parameters need to be adjusted because the patient was overexerted[21]. It also crucial to assess that CIDP patients can complete motion against gravity before applying external resistance to the movement, as it is important to have baseline muscle control before progressing exercises[21].

Recent studies on the effects of exercise programs for patients with CIDP have provided good insight and direction for future physiotherapy treatments. Janssen et al, (2018)[1] completed an intervention that was designed around the Otago Home Exercise programme. This protocol targeted falls prevention, lower limb and core strength exercises with dynamic balance retraining. Their goal was to maximize walking and functional movements required for maintenance and recovery. Patients were prescribed an individualized exercise plan to do three times as well as 30 minute walks twice weekly for a total of 6 weeks. The physiotherapist was able to check in with participants during the 6 weeks. The results demonstrated that a tailored exercise program had a positive effect on a participant’s walking speed and balance in patients with CIDP. More studies will be needed to be able to completely determine the long term impact, however, these are very positive results and should be taken into account when treating a patient with CIDP[1].

Markvandsen et al, (2017)[23] examined the effects of a 12 week aerobic or resistance exercise training programs. The aerobic exercise program involved patients on an ergometer bicycle at home or at a local fitness center for 20-30 minutes 3 times a week. The resistance program, which trained the knee and elbow flexors/extensors on the patient’s weaker side, was completed 3 times a week under the supervision of the authors and each exercise was done repeated 12 times in sets of 3.

During the aerobic training period, VO2 max, 6MWT scores and muscle strength increased. Resistance training also resulted in an increase in muscle strength on the trained, initially weaker, side. The results from this study demonstrate that physical exercise training in patients with CIDP is feasible and effective. Their research determined there was no change in disability, quality of life fatigue severity. The authors hypothesised the lack of change in quality of life was due to the difficulty of 3 times a week exercise and exhaustion following exercise[23]. This must be considered when designing an exercise program for someone with CIDP.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis for CIDP is highly dependent on age at onset, clinical form of the disease, and initial response to treatment[18]. Although not yet validated, it is suggested that increased time between the onset of symptoms and beginning of treatment will result in poor prognosis[18]. For two thirds of people diagnosed, their disease is progressive while the remaining one third have relapsing episodes[13]. The prognosis is good for patients with monophasic or relapsing course of CIDP, and younger patients with rapid onset or a monophasic course are more likely to respond to treatment[18]. Long term remissions after treatment is less frequent in the elderly population compared to juvenile patients or adults aged younger than 64 years[18].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The following outcome measures have been validated for use in individuals with CIDP[1][23][24]:

- Inflammatory neuropathy cause and treatment (INCAT) disability scale and sensory subscore→ measures upper and lower limb dysfunction

- Overall disability sum score (ODSS) → measures the function of the upper and lower limbs

- Overall neuropathy limitations scale (ONLS) → Modified ODSS; ODSS item “Does the patient have difficulty walking?” was changed to “Does the patient have difficulty walking, running or climbing stairs?” The remaining scoring criteria are not different from the ODSS.

- The Rasch-built overall disability scale (RODS) → measures upper and lower limb disability

- GAITrite → measures gait parameters: Velocity, cadence, swing phase, double support time, stance phase

- Timed up and go test (TUG) → Time taken to stand up from a chair, walk a short distance, turn around, return, and sit down again

- 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) → walking speed

- Dynamometer or vigorimeter → measures grip strength

- Manual muscle strength testing and isokinetic strength testing → muscle strength testing

- Fatigue severity scale (FSS) → measures fatigue

- SF-36 → quality of life measure; Physical functioning, role functioning social functioning, body pain,mental health, vitality, general health perception, and change in health

- Chronic Acquired Polyneuropathy Patient reported Index (CAP-PRI) → quality of life measure; physical function, social function, pain, emotional well-being

Some research has utilized other measures, although not validated for the CIDP population[1][23]:

- BERG balance scale → measures balance during the performance of functional tasks

- Visual analogue scale (VAS)

- EQ-5D-5L → Measures self rated health; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression

- VO2 max → measurement of the maximum amount of oxygen that an individual can use during intense exercise

- Combined isokinetic muscle strength → knee and elbow resistance changes

- 6 Minute walk test (6MWT) → walking speed

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Janssen J, Bunce M, Nixon J, Dunbar M, Jones S, Benstead J et al. A clinical case series investigating the effectiveness of an exercise intervention in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Physiotherapy Practice and Research. 2018;39(1):37-44

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Latov N. Diagnosis of CIDP. Neurology. 2002;59(6):S2-S6.

- ↑ IT GBS. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP) 101 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 4 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oDSWrMkvnn0

- ↑ CNS and PNS Explanation. (2018). [image] Available at: https://www.nf2is.org/peripheral_nerve_damage.php [Accessed 7 May 2018].

- ↑ Purpose of Schwann Cells. (2018). [image] Available at: https://socratic.org/questions/in-human-anatomy-what-is-the-purpose-of-the-schwann-cells [Accessed 7 May 2018].

- ↑ Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through clinical cases. 2nd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 2010

- ↑ Center M. CIDP and Cannabis [Internet]. Midwestcompassion.org. 2018 [cited 7 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.midwestcompassion.org/2015/05/18/treating-chronic-inflammatory-demyelinating-polyneuropathy-with-cannabis/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Lewis R. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(1):71-87. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2006.11.003.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Mathey EK, Pollard JD. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2013;333(1-2):37–42

- ↑ Rogosnitzky M, Branch S. Gadolinium-based contrast agent toxicity: a review of known and proposed mechanisms. BioMetals. 2016Jun;29(3):365–76

- ↑ Center M. CIDP and Cannabis [Internet]. Midwestcompassion.org. 2018 [cited 7 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.midwestcompassion.org/2015/05/18/treating-chronic-inflammatory-demyelinating-polyneuropathy-with-cannabis/

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Koller H, Kieseier B, Jander S, Hartung H. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:1343-1356

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Gorson K. An update on the management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 2012;5(6):359-373

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Wolfe, G. and Greer, M. (2015). Diagnosing and Treating CIDP - GBS/CIDP Foundation International. [online] GBS/CIDP Foundation International. Available at: https://www.gbs-cidp.org/ecomm/diagnosing-and-treating-cidp/ [Accessed 7 May 2018].

- ↑ Lewis R. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2017;30(5):508-512

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Allen J, Lewis R. CIDP diagnostic pitfalls and perception of treatment benefit. Neurology. 2015;85(6):498-504

- ↑ Orthosis O. Orthotronix Swedish Trimmable AFO Ankle Foot Orthosis [Internet]. Orthotronix, LLC. 2018 [cited 7 May 2018]. Available from: http://www.orthotronix.com/Orthotronix-Swedish-Trimmable-AFO-Ankle-Foot-Orthosis_p_12.html

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Vallat J-M, Sommer C, Magy L. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for a treatable condition. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(4):402–12

- ↑ Vallat J-M, Sommer C, Magy L. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for a treatable condition. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(4):402–12

- ↑ Manual Therapy – Foul Bay Physio [Internet]. Foulbayphysio.com. 2018 [cited 7 May 2018]. Available from: http://www.foulbayphysio.com/service/manual-therapy/

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Hansen M. Exercise for CIDP. 2010

- ↑ SCIFIT Upper Body Ergometer - Rent Fitness Equipment [Internet]. Rent Fitness Equipment. 2018 [cited 7 May 2018]. Available from: https://rentfitnessequipment.com/catalogue/scifit-upper-body-ergometer/

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Markvardsen L, Overgaard K, Heje K, Sindrup S, Christiansen I, Vissing J et al. Resistance training and aerobic training improve muscle strength and aerobic capacity in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Muscle & Nerve. 2017;57(1):70-76

- ↑ Allan J, Gelinas D, Lewis R, Nowak R, Wolfe G. Optimizing the Use of Outcome Measures in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. US Neurology. 2018;13(1):26-34

![[22]](/images/thumb/a/aa/3-3-2.jpg/200px-3-3-2.jpg)