Cervical Spondylosis

Original Editors - Gertjan Peeters

Top Contributors - Bruno Luca, Rachael Lowe, Jolien Wauters, Scott Cornish, Gertjan Peeters, Deborah Huart, Garima Gedamkar, Kim Jackson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Tony Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Aline Tréfois, Rucha Gadgil, Jess Bell and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

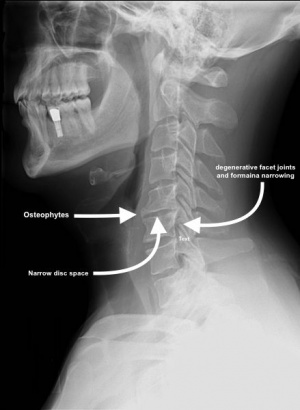

The term spondylosis is used to define a generalised natural ageing process that involves a sequence of degenerative changes in spinal structure.[1][2] In the cervical spine this chronic degenerative process affects the intervertebral discs and facet joints, and may progress to disk herniation, osteophyte formation, vertebral body degeneration, compression of the spinal cord, or cervical spondylotic myelopathy[3]. It has been defined as vertebral osteophytosis secondary to degenerative disc disease due to the osteophytic formations that occur with progressive spinal segment degeneration[1]. The term is often used synonymously with Cervical Osteoarthritis.

Although ageing is the primary cause[1], the location and rate of degeneration as well as degree of symptoms and functional disturbance varies and is unique to the individual.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The cervical spine is made up of seven segments and is highly mobile. [4] It performs 3 important functions; it forms the structural support for the head, protects the cervical spine cord and the exiting nerve roots enclosed within it. [5] There is an important distinction between the high and mid cervical regions and the lower cervical region. The first two vertebrae, the atlas and axis, are anatomically and functionally different segments. The atlas is a uniquely shaped ring without a vertebral body, it articulates with the skull at the atlanto-occipital joint and allows for approximately 33% of the flexion and extension movements of the neck[6]. It pivots on the odontoid process of the axis, which arises from the superior surface of the latter’s body. The atlanto-axial joint is responsible for approximately 60% of the rotational movement in the neck[7]. There is no intervertebral disc between C0-C1 and C1-C2. The lower five cervical vertebrae are roughly cylindrical in shape with bony projections [8]. The intervertebral discs act as shock absorbers, stabilisers and allow the spine to be flexible.

The sides of the vertebrae are linked by small facet joints. Strong ligaments attach to adjacent vertebrae to give extra support and strength. The cervical spine can be split into three columns; anterior, middle and posterior: [8]

- Anterior: consists of the longitudinal anterior ligament , the annulus of the disc and the anterior part of the corpus vertebrae

- Middle: consists of the longitudinal posteriorligament , the posterior part of the annulus and the corpus vertebrae.

- Posterior: All the structures that are posteriorly positioned compared to the longitudinal posterior ligament.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Kelly et al[9] summarised epidemiology studies:

"Evidence of spondylotic change is frequently found in many asymptomatic adults, with 25% of adults under the age of 40, 50% of adults over the age of 40, and 85% of adults over the age of 60 showing some evidence of disc degeneration. Another study of asymptomatic adults showed significant degenerative changes at 1 or more levels in 70% of women and 95% of men at age 65 and 60. The most common evidence of degeneration is found at C5-6 followed by C6-7 and C4-5".

Age, gender and occupation are the risk factors for having cervical spondylosis[10]. The prevalence of cervical spondylosis is similar for both sexes, although the degree of severity is greater for males[11][12][9]. Although ageing is the major risk factor that contributes to the onset of cervical spondylosis[1], repeated occupational trauma may contribute to the development of cervical spondylosis[2]. An increased incidence has been noted in patients who carried heavy loads on their heads or shoulders, dancers, gymnasts, and in patients with spasmodic torticollis, although this cause is not widely accepted. In about 10% of patients, cervical spondylosis is due to congenital bony anomalies, blocked vertebrae, malformed laminae that place undue stress on adjacent intervertebral discs.[13]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Ferrara[1] describes the process of cervical spondylosis as follows:

"Early spondylosis is associated with degenerative changes within the intervertebral disc where desiccation of the disc occurs, thus causing overall disc height loss and a reduction in the ability of the disc to maintain or bear additional axial loads along the cervical spine..... Once the disc starts to degenerate and a loss in disc height occurs, the soft tissue (ligamentous and disc) becomes lax, resulting in ventral and/or dorsal margin disc bulge and buckling of the ligaments surrounding the spinal segment, accompanied by a reduction in the structural and mechanical integrity of the supportive soft tissues across a cervical segment. As the ventral column becomes compromised, there is greater transfer of the axial loads to the uncovertebral joints and also along the dorsal column, resulting in greater loads borne by the facet joints. As axial loads are redistributed to a greater extent along the dorsal column of the cervical spine, the facet joints are excessively loaded resulting in hypertrophic facets with possible long-term ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. When the load balance of the cervical spine is altered and disrupted, as is the situation with cervical degeneration, the remaining functional and supportive structures along the cervical spinal column will absorb the added stress that is transferred to the surrounding structures and adjacent levels along the spine. Eventually these structures will also be excessively loaded, resulting in a cascade of events of further degeneration and tissue adaptation. Overloading the soft tissues and bone eventually causes osteophytes to form in response to excessive loading in order to compensate for greater stresses to the surrounding bone and soft tissue"

Possible degenerative characteristics include:

- Degenerative Disc Disease

- Formation of osteophytes

- Facet and uncovertebral joint degeneration

- Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament

- Hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum causing posterior compression of the cord especially as it buckles in extension

- Spinal stenosis

- Degenerative subluxation of cervical vertebra

- Dislocated fragment of annular cartilage compressing the spinal cord or nerve root [14]

- Neural and vascular compression[1]

In some cases this degeneration also leads to a posterior protrusion of the annulus fibres of the intervertebral disc, causing compression of the nerve roots, pain, motor disturbances such as muscle weakness, and sensory disturbances. As the spondylosis progresses there may even be interference with the blood supply to the spinal cord where the vertebral canal is at its most narrow.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Cervical spondylosis presents in three symptomatic forms as[9]:

- Non-specific neck pain - pain localised to the spinal column.

- Cervical radiculopathy - complaints in a dermatomal or myotomal distribution often occurring in the arms. May be numbness, pain or loss of function.

- Cervical myelopathy - a cluster of complaints and findings due to intrinsic damage to the spinal cord itself. Numbness, coordination and gait issues, grip weakness and bowel and bladder complaints with associated physical findings may be reported.

Symptoms can depend on the stage of the pathological process and the site of neural compression. Diagnostic imaging may show spondylosis, but the patient may be asymptomatic[15] and vice versa. Many people over 30 show similar abnormalities on plain radiographs of the cervical spine, so the boundary between normal ageing and disease is difficult to define[16].

Pain is the most commonly reported symptom. McCormack et al [13] reported that intermittent neck and shoulder pain is the most common syndrome seen in clinical practice. With cervical radiculopathy the pain most often occurs in the cervical region, the upper limb, shoulder, and/or interscapular region [17]. In some cases the pain may be atypical and manifest as chest or breast pain, although it is most frequently present in the upper limbs and the neck. Chronic suboccipital headache could also be a clinical syndrome in patients with cervical spondylosis [18] , which may radiate to the base of the neck and the vertex of the skull.

Paraesthesia or muscle weakness, or a combination of these are often reported and indicate radiculopathy.

Central cord syndrome may also be seen in relation to cervical spondylosis and in some cases dysphagia or airway dysfunction have been reported. [19][20]

Differential Diagnosis[16][edit | edit source]

- Other non-specific neck pain lesions - acute neck strain, postural neck ache or Whiplash

- Fibromyalgia and psychogenic neck pain

- Mechanical lesions - disc prolapse or diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Inflammatory disease - Rheumatoid arthritis, Ankylosing spondylitis or Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Metabolic diseases - Paget's disease, osteoporosis, gout or pseudo-gout, Infections - osteomyelitis or tuberculosis

- Malignancy - primary tumours, secondary deposits or myeloma

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Cervical spondylosis is often diagnosed on clinical signs and symptoms alone[16].

Signs:

- Poorly localised tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Minor neurological changes (unless complicated by myelopathy or radiculopathy)

Symptoms:

- Cervical pain aggravated by movement

- Referred pain (occiput, between the shoulder blades, upper limbs)

- Retro-orbital or temporal pain

- Cervical stiffness

- Vague numbness, tingling or weakness in upper limbs

- Dizzyness or vertigo

- Poor balance

- Rarely, syncope, triggers migraine[21]

Most patients do not need further investigation and the diagnosis is made on clinical grounds alone however, diagnostic imaging such as X-ray, CT, MRI, and EMG can be used to confirm a diagnosis[22].

Plain radiographs of the cervical spine may show a loss of normal cervical lordosis, suggesting muscle spasm, but most other features of degenerative disease are found in asymptomatic people and correlate poorly with clinical symptoms[16]. It is important to realise that radiological changes with age only represent structural changes in the vertebrae, but such changes do not necessarily cause symptoms. It is believed that this mismatch between radiographic appearance and clinical symptoms is not only because of age, but also because of gender, race, ethnic group, height and occupation[10].

MRI of the cervical spine is the investigation of choice if more serious pathology is suspected, as it gives detailed information about the spinal cord, bones, discs, and soft tissue structures. However, normal people can show important pathological abnormalities on imaging so scans need to be interpreted with care[16].

Outcomes Measures[edit | edit source]

The following outcome measures can be used to evaluate neck pain [23]:

- Visual analogue scale (VAS)

- Short Form 36 (SF-36)

- Neck Disability Index (NDI)

Spondylotic changes may result in direct compression and ischemic dysfunction of the spinal cord.[24] Several clinical measures of disease severity have been developed such as the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Cervical Myelopathy Evaluation Questionnaire (JOACMEQ)[25] and the Nurick Classification scoring systems[26]. These popular scales have been developed to quantify the extent and progression of this disease[27].

Pain provocation tests such as Spurling’s test (A) and Bakody’s test (shoulder abduction release test B) can be used to differentiate between shoulder disorders and cervical spondylosis[28].

Examination[edit | edit source]

Muscle atrophy is assessed on the affected side in the upper limb, shoulders and scapular regions and compared with the unaffected side. Muscle strength is tested in 4 muscles representing the myotomes C5-C8. Anterior, middle, and posterior parts of the deltoid muscle are tested by resisting flexion, abduction, and extension of the humerus. Strength of biceps brachii is assessed by resisted elbow flexion when the forearm is supinated. Triceps brachii muscle strength is tested by resisted elbow extension from 90 degrees of elbow flexion. The dorsal interosseus muscles are tested by resisting the separation of the 2nd through 5th fingers. Sensitivity to light touch and to pain are also tested for the relevant cervical dermatomes[29].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Cervical spondylosis is more often seen as a non-progressive chronic condition and most of the related conditions follow a benign course and may be treated with supportive, symptomatic care. Initial management should be nonoperative,[30] only in rare cases is surgery required.

Pharmacology[edit | edit source]

There are various medications used to manage symptoms of cervical spondylosis[31]:

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAID’s) - although there is an absence of clinical trials for the use of NSAIDs in the treatment of cervical spondylosis, but in theory they will reduce inflammation around the nerve, decreasing its sensitivity to compression.

- Opioid analgesics - the use of opoid analgesics has been limited/reduced because of the ineffectiveness in neuropathic pain, in addition to the fear of their addictive nature.

- Muscle relaxants - the use of muscle relaxants is effective for any associated spasm of the trapezius muscle, but the treatment duration is relative short, lasting for a maximum of two weeks.

- Corticosteroids - there is limited evidence to support the use of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy.

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Poor prognostic indicators and absolute indications for surgery are:

- Progression of signs and symptoms that don't respond to conservative management

- Presence of myelopathy for six months or longer

- Compression ratio approaching 0.4 or transverse area of the spinal cord of 40mm squared or less[32].

The goals of surgical treatment of cervical spondylosis are:

- Improvement or preservation of neurological function

- Prevention or correction of spinal deformity[33]

- Maintenance of spinal stability[32]

The mainstay of surgical treatment for degenerative cervical disorders involves decompression of the neural elements often combined this arthrodesis[33]. Decompression may be achieved using an anterior, a posterior, or a combined approach. Recommended decompression is anterior when there is anterior compression at one or two levels and no significant developmental narrowing of the canal. [32]

Anterior decompression, the different surgical options:[34]

- Anterior cervical foraminotomy

- Anterior cervical discectomy without fusion

- Anterior cervical discectomy with fusion

- Cervical arthroplasty

For compression at more than two levels, developmental narrowing of the canal, posterior compression, and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, posterior decompression is recommended: Posterior laminoforaminotomy/foraminotomy and/or discectomy[34]

There continues to be a concern for development of adjacent level disease which has led to the development of total disc arthroplasty.[33]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

- There is little evidence for using exercise alone or mobilisation and/or manipulations alone.

- Mobilisation and/or manipulations in combination with exercises are effective for pain reduction and improvement in daily functioning in sub-acute or chronic mechanical neck pain with or without headache.

- There is moderate evidence that various exercise regimens, like proprioceptive, strengthening, endurance, or coordination exercises are more effective than usual pharmaceutical care[35][36][37].[3a;4;5]

Treatment should individualised, but generally includes rehabilitation exercises, proprioceptive re-education, manual therapy and postural education[38][39]:[1b;1b]

Manual therapy is defined as high-velocity; low-amplitude thrust manipulation or non-thrust manipulation. Manual therapy of the thoracic spine can be used for reduction of pain, improving function, to increase the range of motion and to address the thoracic hypomobility[40][3b]

Thrust manipulation of the thoracic spine could include techniques in a prone, supine, or sitting position based on therapist preference. Also cervical traction can be used as physical therapy to enlarge the neural foramen and reduce the neck stress [34] [2a]

Non-thrust manipulation included posterior-anterior (PA) glides in the prone position. The cervical spine techniques could include retractions, rotations, lateral glides in the ULTT1 position, and PA glides. The techniques are chosen based on patient response and centralisation or reduction of symptoms.[39][1b]

Postural education includes the alignment of the spine during sitting and standing activities.[39][1b]

Thermal therapy provides symptomatic relief only and ultrasound appears to be ineffective[41].[1b]

Soft tissue mobilisation was performed on the muscles of the upper quarter with the involved upper extremity positioned in abduction and external rotation to pre-load the neural structures of the upper limb.[41][1b]

Home Exercices include cervical retraction, cervical extension, deep cervical flexor strengthening, scapular strengthening, stretching of the chest muscles via isometric contraction of flexor of extensor muscles to encourage the mobility of the neural structures of the upper extremity.[40] [41] [3b;1b]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Cervical Spondylosis is a normal degenerative disorder of the cervical spine. Whether spondylosis should be considered a degenerative change or an age related change is simply a matter of semantics, but the development of osteophytes and related changes can be viewed as a reactive and adaptive change that seeks to compensate for biomechanical aberrations. Approximately 95% of people by age 65 have cervical spondylosis to some degree, it’s the most common spine dysfunction in elderly people. The symptoms can depend on the stage of the pathologic process and the site of neural compression. In many cases, on imaging spondylosis can seen to be present, but the patient may not have any symptoms. Cervical spondylosis is mostly diagnosed on clinical signs and symptoms alone. Treatment should be tailored to the individual patient and include supervised isometric exercises, proprioceptive reeducation, manual therapy and posture education.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Ferrara LA. The biomechanics of cervical spondylosis. Advances in orthopedics. 2012 Feb 1;2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Moon MS, Yoon MG, Park BK, Park MS. Age-Related Incidence of Cervical Spondylosis in Residents of Jeju Island. Asian spine journal. 2016 Oct 1;10(5):857-68.

- ↑ Xiong W, Li F, Guan H. Tetraplegia after thyroidectomy in a patient with cervical spondylosis: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(6):e524.

- ↑ Boek R. Putz, R. Pabst. Sobotta, Atlas of Human Anatomy Volume 1: Head, Neck, Upper Limb.2006.Elsevier.

- ↑ Ippei Takagi, Cervical Spondylosis: An Update on Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestation, and Management Strategies. DM, October 2011

- ↑ Amiri M, Jull G, Bullock-Saxton J. Measurement of upper cervical flexion and extension with the 3-space fastrak measurement system: a repeatability study. J Man Manip Ther 2003;11(4): 198–203.

- ↑ Salem W, Lenders C, Mathieu J, et al. In vivo three-dimensional kinematics of the cervical spine during maximal axial rotation. Man Ther 2013;18:339–44.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 McCormack B M, Weinstein P R, Cervical Spondylosis. An update. Western Journal of Medicine, Jul-Aug 1996

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kelly JC, Groarke PJ, Butler JS, Poynton AR, O'Byrne JM. The natural history and clinical syndromes of degenerative cervical spondylosis. Advances in orthopedics. 2011 Nov 28;2012.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Singh S, Kumar D, Kumar S. Risk factors in cervical spondylosis. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2014 Dec 31;5(4):221-6.

- ↑ D.H. Irvine, J.B. Foster, Prevalence of cervical spondylosis in a general practice, The Lancet, May 22 1965

- ↑ Sandeep S Rana, MD, Diagnosis and Management of Cervical Spondylosis. Medscape, 2015

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 McCormack BM, Weinstein PR. Cervical spondylosis. An update. West J Med. Jul-Aug 1996;165(1-2):43-51.

- ↑ Torrens M, Cervical Spondylosis Part 1: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management Options

- ↑ Takagi I, Cervical Spondylosis: An Update on Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestation, and Management Strategies. DM, October 2011

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2007 Mar 10;334(7592):527.

- ↑ Ellenberg MR, Honet JC, Treanor WJ. Cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Mar 1994;75(3):342-52

- ↑ Heller JG. The syndromes of degenerative cervical disease. Orthop Clin North Am. Jul 1992;23(3):381-94. (Level: A1)

- ↑ Kaye JJ, Dunn AW. Cervical spondylotic dysphagia. South Med J. May 1977;70(5):613-4. (Level: A1)

- ↑ Kanbay M, Selcuk H, Yilmaz U. Dysphagia caused by cervical osteophytes: a rare case. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jul 2006;54(7):1147-8. (Level: C)

- ↑ Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain: clinical review. BMJ 2007:334:527-31

- ↑ Zhijun Hu et al., A 12-Words-for-Life-Nurturing Exercise Program as an Alternative Therapy for Cervical Spondylosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial, 20 March 2014

- ↑ J. Lafuente, A.T.H. Casey, A. Petzold, S. Brew, The Bryan cervical disc prosthesis as an alternative to arthrodesis in the treatment of cervical spondylosis, The Bone and Joint Journal, 2005.

- ↑ M. Pumberger, D. Froemel, Clinical predictors of surgical outcome in cervical spondylotic myelopathy, The Bone and Joint Journal, 2013

- ↑ Fukui M, Chiba K, Kawakami M, Kikuchi SI, Konno SI, Miyamoto M, Seichi A, Shimamura T, Shirado O, Taguchi T, Takahashi K. Japanese orthopaedic association cervical myelopathy evaluation questionnaire (JOACMEQ): Part 2. Endorsement of the alternative item. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2007 May 1;12(3):241.

- ↑ Revanappa KK, Rajshekhar V. Comparison of Nurick grading system and modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scoring system in evaluation of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. European Spine Journal. 2011 Sep 1;20(9):1545-51.

- ↑ D.R. Lebl, A. Hughes, P.F. O’Leary, Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment, the Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery, Jul 2011.

- ↑ Hyun-Jin Jo et al., Unrecognized Shoulder Disorders in Treatment of Cervical Spondylosis Presenting Neck and Shoulder Pain, The Korean Spinal Neurosurgery Society, 9(3):223-226, 2012

- ↑ EIRA Viikari-Juntura, Interexaminer Reliability of Observations in Physical Examinations of the Neck, Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association

- ↑ Kieran Michael Hirpara, Joseph S. Butler, Roisin T. Dolan, John M. O'Byrne, and Ashley R. Poynton , Nonoperative Modalities to Treat Symptomatic Cervical Spondylosis, Advances in Orthopedics, 2011

- ↑ Hirpara KM, Butler JS, Dolan RT, O'Byrne JM, Poynton AR. Nonoperative modalities to treat symptomatic cervical spondylosis. Advances in orthopedics. 2011 Aug 1;2012.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Melvin D. Law, Jr., M.D.a, Mark Bemhardt, M.D.b, and Augustus A. White, III, M.D., Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: A Review of Surgical Indications and Decision Making, Yale journal of biology and medicine,1993

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Todd AG. Cervical spine: degenerative conditions. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2011 Dec 1;4(4):168.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Kyoung-Tae Kim and Young-Baeg Kim, Cervical Radiculopathy due to Cervical Degenerative Diseases : Anatomy, Diagnosis and Treatment, The Korean Neurosurgical Society, 2010 (Level: 2a)

- ↑ Rahim KA, Stambough JL. Radiographic evaluation of the degenerative cervical spine. Orthop Clin North Am. Jul 1992;23(3):395-403. (Level: 3a)

- ↑ Heller JG. The syndromes of degenerative cervical disease. Orthop Clin North Am. Jul 1992;23(3):381-94. (Level: 4)

- ↑ Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain: clinical review. BMJ 2007:334:527-31 (Level: 5)

- ↑ Kieran Michael Hirpara, Joseph S. Butler, Roisin T. Dolan, John M. O'Byrne, and Ashley R. Poynton , Nonoperative Modalities to Treat Symptomatic Cervical Spondylosis, Advances in Orthopedics, 2011 (Level: 1b)

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 . Ian A. Young, Lori A. Michener, Joshua A. Cleland, Arnold J. Aguilera, Alison R. Snyde, Manual Therapy, Exercise, andTraction for Patients With Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial, 2009 (Level: 1b)

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Michale Costello, Treatment of a Patient with Cervical Radiculopathy Using Thoracic Spine Thrust Manipulation, Soft Tissue Mobilization, and Exercise, the Journal of Manual and manipulative therapy (Level: 3b)

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Ibrahim M. Moustafa and Aliaa A. Diab, Multimodal Treatment Program Comparing 2 Different Traction Approaches for Patients With Discogenic Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Journal of Chiropractic Medicine (2014) 13, 157–167 (Level: 1b)