Cervical Osteoarthritis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

== Medical Management == | == Medical Management == | ||

The following medical management strategies are only indicating when all other conservative treatment has failed. | |||

==== < | === Intra-articular Injections === | ||

Intra-articular corticosteroids are recommended for hip and knee osteoarthritis. The effects of corticosteroids on cervical osteoarthritis need to be researched <ref name="cibulka" /> <ref name="mqic" /> <ref name="peter" /> <ref name="loew" />. | |||

=== Surgical treatment === | |||

There are indications that excision and fusion of the anterior cervical intervertebral disc (Cloward operation) together with the removal of associated arthritic bone spurs pressing on the nerves and spinal cord can give relief of pain and muscle weakness in patients who have cervical osteoarthritis with neurologic pain <ref name="robert">Robert W. Rand and Paul H. Crandall, Surgical treatment of cervical osteoarthritis, Calif Med. 1959 Oct; 91(4): 185–188.</ref>. | There are indications that excision and fusion of the anterior cervical intervertebral disc (Cloward operation) together with the removal of associated arthritic bone spurs pressing on the nerves and spinal cord can give relief of pain and muscle weakness in patients who have cervical osteoarthritis with neurologic pain <ref name="robert">Robert W. Rand and Paul H. Crandall, Surgical treatment of cervical osteoarthritis, Calif Med. 1959 Oct; 91(4): 185–188.</ref>. | ||

=== | === Transarticular screw fixation === | ||

Patients with atlantoaxial (C1-C2) facet joint osteoarthritis have a positive reaction on pain after the fusion of these two facet joints. This treatment has a relative low rate of serious complications <ref name="grob" />.<u></u> | Patients with atlantoaxial (C1-C2) facet joint osteoarthritis have a positive reaction on pain after the fusion of these two facet joints. This treatment has a relative low rate of serious complications <ref name="grob" />.<u></u> | ||

=== | === Laminoplasty === | ||

Laminoplasty is used to decompress the cervical spinal cord. A risk of this surgical treatment is a reduced strength and shear stiffness (SS) of motion segments. As a result of this, the patient can suffer from instability. Also a great part of the patients had neck pain after the surgical the method of Kuang-Ting Yeh choses laminoplasty instead of laminectomy as a decompression method in posterior instrumented fusion for degenerative cervical kyphosis with stenosis <ref name="arno" />. In short-terms there are some benefits from chondroitin (alone or in combination with glucosamine). Benefits are small to moderate but clinically meaningful <ref name="singh" />. | |||

== Physical Therapy Management == | == Physical Therapy Management == | ||

Revision as of 11:05, 21 August 2017

Original Editors - Bram Sorel

Top Contributors - Lisa Pernet, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Nina Myburg, Rachael Lowe, Kenneth de Becker, Kim Jackson, Scott Cornish, Admin, Jason Coldwell, Bram Sorel, Evan Thomas, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Nicolas Casier, WikiSysop and Rucha Gadgil

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

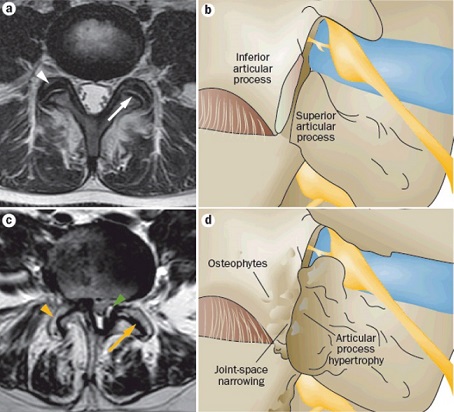

The cervical spine consists of seven cervical vertebrae which are situated between the skull and the thoracic region. Osteoarthritis of the cervical spine may be defined as a degenerative disorder at those levels, complicated by inflammatory reactions. It is a very complex disease with multiple causes[1] which affects the intervertebral discs, vertebral bodies, intervertebral ligaments,[2] the hyaline cartilage, the underlying bone, joint capsule, zygophyseal joints and/or can lead to the formation of osteophytes [3] [4] or subchondral cysts and/or can cause hypertrophy of the articular process.[5] Although cervical osteoarthritis is often referred to as cervical spondylosis [4], it is not clear whether these two concepts may be considered synonyms.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

For a overview of the components which form the cervical spine see http://www.physiopedia.com/Category:Cervical_Anatomy

These are the cervical spine components that are affected by osteoarthritis;

- Articular cartilage [1] [6] Initially fibrillation and shallow pitting occur, which affect the surface of the cartilage focally at first. At a more progressed stage, this can evolve to deeper fibrillation and fissuring, peeling off and pitting until the subchondral bone is affected. [5]

- Synovium[1]

- Uncovertebral joints: Osteophytes are formed on the articular surfaces of the uncinate process. These osteophytes can impinge anatomical structures like the cervical spinal cord, spinal nerve root, radicular artery, vertebral artery and cervical sympathetic trunk.[7]

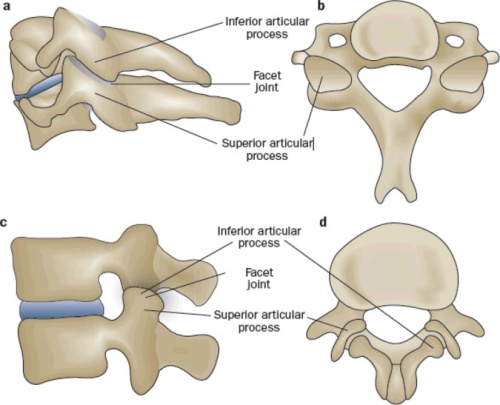

- Facet joints (Figure 2): which are inclined 45° from the horizontal. The joint surfaces are generally planar, but not flat.[5]

- Intervertebral discs: between C0–C1 and C1-C2 there is no intervertebral discs. Major factors in the development and progression of osteoarthritis of the facet joints are Joint alignment and load distribution.[5]

- Cervical plexus: Osteophyte formation or progressive cartilage thinning may narrow the intervetebral foramin through which the cervical nerve roots emerge.[5] [8]

- Intervertebral ligaments.[2]

There is a 'three joint complex' at every spinal level except C1–C2. This motion segment, is formed by the three articulations between adjacent vertebrae. These three articulations consist of one disc and two facet joints. The superior articular processes of the lower vertebra is positioned upwards and will articulate with the smaller inferior articular processes of the vertebra above it. The cervical facet articular surface area is about two-thirds the size of the area of the vertebral end plate. The facet joint exhibits features typical of synovial joints: articular cartilage covers the opposed surfaces of each of the facets, resting on a thickened layer of subchondral bone, and a synovial membrane bridges the margins of the cartilaginous portions of the joint. A superior and inferior capsular pouch, filled with fat, is formed at the poles of the joint, and a baggy fibrous joint capsule covers the joint like a hood. A fibro adipose menisci projects into the superior and inferior aspect of the joint and consists of a fold of synovium that encloses fat, collagen, and blood vessels. These menisci’s serve to increase the contact surface area when the facets are brought into contact with one another during motion, and slide during flexion of the joint to cover articular surfaces exposed by this movement. [9]

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Cervical osteoarthritis may be generalised, sometimes involving the entire cervical region, but it is usually more localised between the 5th and 6th and the 6th and 7th cervical vertebrae.

Anyone can develop cervical osteoarthritis, but it is rare in people younger than 40-50 years, the incidence increasing with age, [10] [6]women having a higher risk for cervical OA than men.[10] [3] It is common in people above the age of 50 and especially if those people had had jobs that included remaining in a single static position for long periods, i.e. reading, writing and other desk based careers.

Incidence of cervical OA can have many causes. i.e. mechanically over-stressing of a joint (e.g. working with tools which generate intense vibration), previous bone fractures or other injuries to the neck, overload at young age, postural asymmetry or asymmetric loading of a joint. Hartz et al suggest that there is a relationship between the severity of cervical osteoarthritis and a higher body weight of the patient.[4]

Facet joint osteoarthritis (FJ OA) is intimately linked to the distinct but functionally related condition of degenerative disc disease, which affects structures in the anterior aspect of the vertebral column. FJ OA and degenerative disc disease are both thought to be common causes of back and neck pain, which in turn have an enormous impact on the health-care systems and economies of developed countries. [9]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

OA is characterised by pain, stiffness, crepitus, limited range of movement and sometimes joint instability and mild synovitis [11] [12] [13] The pain is usually localised around the affected joint, but referred pain may occur. Pain associated with FJ OA can arise from nociceptors within and surrounding the joints, including nociceptors in the bone itself, as the facet joints and their capsules are well innervated [14]. Pain can radiate to the occiput, the medial border of the scapula and the upper limbs [15]. Pain often becomes worse with joint movement and can be more severe at the end of the day. Morning stiffness can be a common feature, but usually dissipates quickly [16]. Restricted movement can occur due to pain, capsular thickening and the presence of osteophytes [16].

Pressure symptoms in the cervical spine are caused by osteoarthritis of the uncovertebral joints. Osteophytes can form around the intevertbral joints and cause neurological symptoms due to compression of the spinal nerves [17]. Narrowing of the spinal canal can also cause circulation problems. Performing an MRI can be useful to confirm the presence of any compression of the spinal cord.

Prolonged peripheral inflammation in and around facet joints can lead to central sensitisation, neuronal plasticity, and the development of chronic spinal pain [18]. There are potential red flags which may indicate a more serious issue [19]:

- Malignancy, infection, or inflammation

- Fever, night sweats

- Unexpected weight loss

- History of inflammatory arthritis, infection, tuberculosis, HIV infection, drug dependency, or immunosuppression

- Excruciating pain

- Intractable night pain

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

- Exquisite tenderness over a vertebral body

- Myelopathy

- Gait disturbance or clumsy hands, or both

- Objective neurological deficit

- Sudden onset in a young patient suggests disc prolapse

- History of severe osteoporosis

- Drop attacks, especially when moving the neck, suggest vascular disease

- Intractable or increasing pain

http://www.spine-health.com/video/cervical-facet-osteoarthritis-video

Differential Diagnosis [20] [21][edit | edit source]

- Other non-specific neck pain lesions: acute neck strain, postural neck ache, or whiplash

- Fibromyalgia and psychogenic neck pain

- Mechanical lesions: disc prolapse

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Inflammatory disease: rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriatric arthritis, septic arthritis, reactive arthritis

- Metabolic diseases: Paget’s disease, osteoporosis, gout, or pseudo-gout

- Osteomyelitis or tuberculosis

- Malignancy: primary tumors, secondary deposits, or myeloma

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

A diagnosis is usually based on the clinical presentation [22] [1]

• Pain on range of motion

• Limitation of range of motion

• Lower extremity sensory loss, reflex loss, motor weakness caused by nerve root impingement

• Pseudoclaudication caused by spinal stenosis

Radiology can also be used to determine OA, but some people with radiological signs can remain asymptomatic [1]. Kellgren and Lawrence developed a grading system for the radiological appearance of a joint with osteoarthritis [2].

| Radiological appearance of osteoarthritis | Grade |

|---|---|

| normal (no signs of osteoarthritis) | 0 |

| doubtful change (uncertain) | 1 |

| definite, minimal to mild | 2 |

| definite, moderate | 3 |

| definite, severe | 4 |

If more than one joint in a group is assessed, then the most severe grade is reported.

Parameters:

- osteophytes at the joint margins and periarticular ossicles

- narrowing of the joint space

- cystic areas with sclerotic walls in subchondral bone

- deformity of bone (altered shape)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Functional status and disability measure (evaluation of the activities of daily living) can be assessed by the “Neck Pain and Disability Scale” (NPAD) and the “Neck disability index (NDI)”.[23]

- The Neck pain and disability scale (NPAD) is a composite index including 20 items, which measure the intensity of neck pain, its interference with vocational, recreational, social, and functional aspects of living and also the presence and extent of associated emotional factors.

- The Neck disability index (NDI) is a patient completed and condition specific functional status questionnaire. This questionnaire consists of 10 items, including pain, personal care, lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleeping and recreation. This questionnaire has been designed to give information as to how neck pain has affected the patient’s ability to manage in daily life.

The NPAD and NDI are both seen as valid measures of self-reported neck pain related disabilities.[23]

Examination[edit | edit source]

As osteoarthritis is primarily a clinical diagnosis, patient history and the physical examination is usually sufficient to make a confident diagnosis. Joint pain and limited range of motion are usual symptoms in patients with cervical osteoarthritis. The pain tends to worsen with activity, especially following a period of rest (gelling phenomenon). [24]

Electromyographic analysis shows a higher fatigue of the anterior and posterior neck muscles compared with healthy subjects.[25]

Physical examination includes:[5]

- Inspection: posture, edema, erythema, evidence of trauma, muscle atrophy, skin abnormalities and joint deformity.

- Palpation of facet joints, examining of anatomic abnormality, temperature and tenderness.

- Range of motion of the cervical region and shoulder region.

- Stress of the facet joints: pain increases with hyperextension, extension-rotation of the neck. Pain decreases while doing flexion of the neck.

- Motor- and sensory evaluation: L’hermitte sign: sense of feeling electrical shocks in both arms or legs while performing neck flexion.

- Muscle testing: searching myofascial triggerpoints in the m. sternocleidomastoideus, cervical paraspinal muscles, m. levator scapulae, the upper trapezius and suboccipital musculature.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The following medical management strategies are only indicating when all other conservative treatment has failed.

Intra-articular Injections[edit | edit source]

Intra-articular corticosteroids are recommended for hip and knee osteoarthritis. The effects of corticosteroids on cervical osteoarthritis need to be researched [14] [15] [16] [17].

Surgical treatment[edit | edit source]

There are indications that excision and fusion of the anterior cervical intervertebral disc (Cloward operation) together with the removal of associated arthritic bone spurs pressing on the nerves and spinal cord can give relief of pain and muscle weakness in patients who have cervical osteoarthritis with neurologic pain [26].

Transarticular screw fixation[edit | edit source]

Patients with atlantoaxial (C1-C2) facet joint osteoarthritis have a positive reaction on pain after the fusion of these two facet joints. This treatment has a relative low rate of serious complications [11].

Laminoplasty[edit | edit source]

Laminoplasty is used to decompress the cervical spinal cord. A risk of this surgical treatment is a reduced strength and shear stiffness (SS) of motion segments. As a result of this, the patient can suffer from instability. Also a great part of the patients had neck pain after the surgical the method of Kuang-Ting Yeh choses laminoplasty instead of laminectomy as a decompression method in posterior instrumented fusion for degenerative cervical kyphosis with stenosis [12]. In short-terms there are some benefits from chondroitin (alone or in combination with glucosamine). Benefits are small to moderate but clinically meaningful [13].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The main goals of management for cervical OA are: [10]

- reducing pain and stiffness

- improving joint mobility

- inhibiting further progression of joint damage

Treatment for cervical osteoarthritis is usually conservative and it can be treated using a variety of therapy possibilities with exercise therapy being a key element. Exercise includes mobilisation exercises, strengthening local muscles around the affected joint and improving overall aerobic fitness. [10] [23] [2]

There is considerable evidence that suggests that physical activity can help in in the management of chronic pain and should play a key role in overall treatment. This will improve the disability over time and has other multiple health benefits.

Therapy options are:

Heat and cold modalities [edit | edit source]

Even though there is a lack of evidence for the application of local heat or cold, it is often used by patients with OA to decrease pain.

Manual therapy[edit | edit source]

Manual therapy, such as massage, mobilisation, and manipulation, may provide further relief for patients with cervical osteoarthritis. Mobilisation is characterised by the application of gentle pressure within or at the limits of normal motion to improve ROM. It is important not to go into pain.

Manipulation may be considered, but there are numerous contraindications, such as myelopathy, severe degenerative changes, fracture or dislocation, infection, malignancy, ligamentous instability and vertebrobasilar insufficiency which have to be taken into consideration. [27]

Pulsed electric stimulation[edit | edit source]

This treatment causes the stimulation of cartilage growth at the cellular level, yet there is a need for further large scale studies of pulsed electric stimulation to confirm these finding.[18] It is thought that magnetic therapy represents an alternative therapy for patients suffering from cervical OA. Electromagnetic fields can be applied to treat cervical OA and are thought to have a pain-relief effect, but further studies are needed. [2] [28] [18]

Hydrotherapy[edit | edit source]

Underwater traction of the cervical spine during weightbath therapy demonstarated positive outcomes; it mitigated the pain, increased the range of motion and improved quality of life. The patient hangs in a steel construction with their head supported by a collar which creates the traction and their body weight supported by the water. [29] [30]

Acupuncture[edit | edit source]

- Studies have shown minimal significant benefits of acupuncture for osteoarthritis which do not meet the defined thresholds for clinical relevance. Most of the benefits are suggested to be placebo.[19]

- Nakijima et al suggested that the depth of the needle has significant relevance for long-term benefit. The results showed that a deeper needle insertion (15-20mm) was more effective than a superficial one (5mm) in patients with neck and shoulder pain.[31]

Postural awareness[edit | edit source]

Advice and education regarding good neck posture is a key part of treatment as as the condition progresses, neck posture can negatively alter. Side lying is the preferred position when sleeping as lying supine. A single pillow only under the head for head support is suggested, although a butterfly pillow offers the best support, as it is flattened in the middle and the elevated sides support the head. [32]

Ultrasound[edit | edit source]

Ultrasound may be beneficial, but there is only low quality evidence for its effectiveness on osteoarthritis. Most studies however have investigated its effectiveness on hip and knee osteoarthritis. The magnitude of the effects on pain relief and function is still unclear and any positive results may wholly be due to placebo.[20]

TENS[edit | edit source]

TENS can also provide symptomatic relief. [10] [23] [2]

Neck support[edit | edit source]

Immobilisation of the neck can be achieved with both soft or more rigid collars, but they should be used in combination with exercises and their limited to avoid dependence.[33]

Low power Laser Therapy[edit | edit source]

Several studies have shown the effectiveness of low power laser therapy. They demonstrated a reduction in pain and an improvement in neck function. Chow et al compared low laser therapy with a placebo treatment. The treatment group showed significant improvement on several parameters: pain, paravertebral muscle spasm, lordosis angle and range of motion of the neck.[34] [35] [36]

Neck exercises[edit | edit source]

Resistance Band Exercises[edit | edit source]

Thera-band: 6 color-coded levels of resistance (red, green, blue, black, silver and gold)

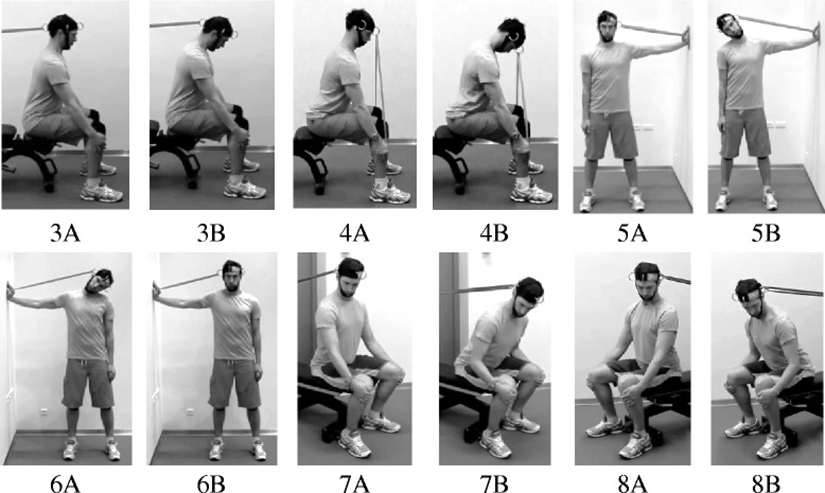

A training program consisted of four training exercises for the prime movers of the neck during cervical flexion, extension and lateral flexion. Exercises were performed with a head harness (Neck Flex) using different color-coded elastic resistance bands (Thera-Band®).

During the exercises it is advised to maintain a proper posture:

• Keep a straight back

• Position their head in an anatomically neutral position

• Lean the trunk forward (~20-30°)

• Arms were held straight with the hands placed underneath the knees.

Cervical flexion against resistance (Fig. 3)

A Thera-Band is stretched between a door anchor and the back of the head harness. During the exercise, the participants have to perform a low cervical spine flexion (against resistance) followed by a low cervical spine extension.

Cervical extension against resistance (Fig. 4)

During neck extension, participants are positioned in the same way as during neck flexion, but the Thera-Band is stretched between the hands and front of the head harness. The exercise is performed with a low cervical spine flexion followed by a low cervical spine extension (against resistance)

Lateral flexion against resistance (Fig. 5, 6)

Lateral flexion is performed standing erect with the head in an anatomically neutral position. One hand has to be placed horizontally against a wall and a Thera-Band is stretched between the hand and side of the head harness. The exercise is performed with a low lateral spine flexion followed by a low lateral spine extension (against resistance). The exercise has to be performed for the right (Fig. 3, Exercise 5) and left side.

Flexion and rotation against rotation (Fig. 7, 8)

This exercise can be introduced afterwards as a complementary part of the therapy. The exercise is performed seated with a straight back and trunk leaned forward (~20°). The head is held in an anatomically neutral position and rotated approximately 45° degrees to either the right or left side. A Thera-Band has to be stretched between the head harness and a door anchor.

Keeping a static upper body, the hips has to be flexed and the body also (against resistance) this is followed by an extension. The exercise has to be performed to the right and left side. [22]

Advice and education[edit | edit source]

Providing information related to the disorder, stress management and postural advice in daily activities, work and hobbies should also be part of any treatment plan [23] providing encouragement and motivation. [21]

Proprioceptive exercises[edit | edit source]

Proprioceptive exercises can also be used in the therapy of cervical osteoarthritis. Some studies have shown a positive result in using proprioceptive exercises. [37] [38]

Stabilisation exercises[edit | edit source]

Exercises with for example © Chattanooga stabilizer pressure biofeedback can help to train the deep cervical flexor muscles. Stabilization exercises have been proven to be effective for the reduction of pain in patients with cervical pain due to cervical osteoarthritis.[39]

Stretching exercises[edit | edit source]

A regular stretching exercise program performed for four weeks can decrease neck and shoulder pain and improve neck function and quality of life of people who suffer of cervical osteoarthritis. [40]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Musumeci G, Aiello FC, Szychlinska MA, Di Rosa M, Castrogiovanni P, Mobasheri A. Osteoarthritis in the XXIst Century: Risk Factors and Behaviours that Influence Disease Onset and Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2015; 16(3): 6093-6112

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Sutbeyaz ST, Sezer N, Koseoglu BF. The effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of cervical osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. Rhematol Int 2006; 26: 320-324

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Michael J. Lee, K.Daniel Riew. The prevalence cervical facet arthrosis: an osseous study in cadaveric population. The spine Journal 9(2009) 711-714

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hartz A J, Fisher M E, Bril G, et al. The association of obesity with joint pain and osteoarthritis in the HANES data. J Chronic Dis 1986;39:311-319

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Gellhorn AC, Katz JN, Suri P. Osteoarthritis of the spine: the facet joints. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013; 9(4): 216-224

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Boucher P. Postural control in people with osteoarthritis of the cervical spine. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 2008; 31(3): 184-190

- ↑ Hartman J, Anatomy and Clinical Significance of the Uncinate Process and Uncovertebral Joint: A Comprehensive Review. Clinical Anatomy 2014; 27: 431-440

- ↑ Rand RW, Crandall PH. Surgical Treatment of Cervical Osteoarthritis. Calif Med 1959; 91(4): 185-188

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Alfred C. Gellhorn et al., Osteoarthritis of the spine: the facet joints, Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 April ; 9(4): 216–224

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Walker JA, Osteoarthritis: pathogenesis, clinical features and management. Nursing Standard 2009, Vol. 24, Nr. 1, 35-40

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Grob D. et al., Transarticular screw fixation for osteoarthritis of the atlanto-axial segment, Eur spine journal 2006 Mar; 15(3):283:91

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Arno Bisschop, Which factors prognosticate spinal instability following lumbar laminectomy?,Eur Spine J. 2012 Dec; 21(12): 2640–2648.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Singh J.A. et al., Chondroitin for osteoarthritis, 2015, Cochrane review.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Cibulka M.T. et al., Hip pain and mobility deficits - hip osteoarthritis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 39 (2009), pp A1-25

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 MQIC, Medical management of adults with osteoarthritis, Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium (2011)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Peter W.F. et al., Physiotherapy in hip and knee osteoarthritis: development of practice guideline concerning initial assessment, treatment and evaluation, Acta Reumatol Port, 36 (2011), pp 268-281.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Loew L. et al, Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic walking programs in the management of osteoarthritis, Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 93 (2012), pp 1269-1285.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Hulme J. et al., Electromagnetic fields for the treatment of osteoarthritis., Hulme J1, Robinson V, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Manheimer E. et al., Acupuncture for osteoarthritis, 2010, Cochrane review.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Rutjes A. W. S. et al., Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis, 2010, Cochrane review.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Marley J; et al. A systematic review of interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain, Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 19; 3:106)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Mike Murray et al. Specific exercise training for reducing neck and shoulder pain among military helicopter pilots and crew members: a randomized controlled trial protocol, BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015; 16: 198.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Binder A, Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ. 2007 Mar 10;334(7592):527-531

- ↑ Sinusas K., Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment, Am Fam Physician, 2012 Jan 1;85(1):49-56.

- ↑ Gogia et al.; Electromyograhic Analysis of Neck Muscle Fatigue in Patients With Osteoarthritis of the Cervical Spine. Cervical Spine/Basic Science march 1994

- ↑ Robert W. Rand and Paul H. Crandall, Surgical treatment of cervical osteoarthritis, Calif Med. 1959 Oct; 91(4): 185–188.

- ↑ Almeida GP, Carneiro KK, Marques AP. Manual therapy and therapeutic exercise in patient with symptomatic cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a comprehensive review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013 Oct;17(4):504-9.

- ↑ David H. Trock, Alfred Jay Bollet and Richard Markoll; The effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and cervical spine. Report of randomized, Double blind, placebo controlled trial ; J Rheumatol 1994

- ↑ Mihaly Olah, Levente Molnar, Jozsef Dobai ;The effects of weightbath traction hydrotherapy as e component of complex physical therapy in disorders of the cervical and lumbar spine: a controlled pilot study with follow up; 12 January 2008

- ↑ Márta Kurutz and Tamás Bender ; Weightbath hydrotraction treatment: application, biomechanics, and clinical effects ; Journal of multidisciplinary Healthcare ; April 2010

- ↑ Nakajima et al., Difference in Clinical Effect between Deep and Superficial Acupuncture Needle Insertion for Neck-shoulder Pain: a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Pilot Study, January, 23, 2015

- ↑ Kieran Michael Hirpara, Joseph S. Butler, Roisin T. Dolan, John M. O'Byrne, and Ashley R. Poynton. Nonoperative Modalities to Treat Symptomatic Cervical Spondylosis. Adv Orthop. 2012; 2012: 294857.

- ↑ Sandeep S Rana ; Diagnosis and Management of Cervical Spondylosis Treatment & Management ;Augustus 2015

- ↑ F. Özdemir, M. Britane and Kokino ; Department of Physical therpy and rehabilitation, Medical faculty of Trakya university ;The clinical efficacy of low-power laser therapy on pain and function in Cervical Osteoarthritis. ; Clinical Rheumatology , 2001 , Turkey

- ↑ Bjordal et al: A systematic review of low level laser therapy with location-specific doses for pain from joint disorders; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 2003 Vol. 49, 107-116

- ↑ Chow RT. et al; efficacy of low level laser therapy in the management of neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo or active-treatment controlled trials; the lancet; nov 13,2009

- ↑ Michael A McCaskey et al.; Effects of proprioceptive exercises on pain and function in chronic neck- and low back pain rehabilitation: a systematic literature review; BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders BMC series – open, inclusive and trusted 201415:382

- ↑ A.R. Gross et al.; Exercises for mechanical neck disorders: A Cochrane review update; Manual Therapy 24 (2016) 25-45

- ↑ Dusunceli Yesim et al.; Efficacy of neck stabilization exercises for neck pain: A randomized controlled study; Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, Volume 41, Number 8 ( level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Tunwattanapong P et al.; The effectiveness of a neck and shoulder stretching exercise program among office workers with neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016 Jan;30(1):64-72.