Cellulitis

Original Editors - Students from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kacie McClendon, Elaine Lonnemann, Erica Shelley, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Fasuba Ayobami, 127.0.0.1, Karen Wilson, Vidya Acharya, Claire Knott, Evan Thomas and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Cellulitis is a localized bacterial skin infection, which typically affects the lower limbs but can occur on any area of skin and underlying subcutaneous tissue. It is characterized by acute onset of redness, inflammation, pain, and swelling of the affected area. Accompanying symptoms include:

- Generalized fever

- Rigors

- Nausea

- Vomiting.[2]

The infection is most commonly caused by B-Hemolytic Streptococci bacteria and reoccurs up to 50% of the time in the lower extremity.[3] Most individuals diagnosed with cellulitis have a low risk of severe complications but few sufferers can have:

- Severe sepsis

- Local gangrene

- and/or Necrotizing fasciitis.[2]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

- 650,000 hospital admissions per year in the United States are due to cellulitis.[4]

- When hospitalized, patients with recurrent cellulitis require longer hospitalizations relative to nonrelapsing cellulitis patients.[4]

- From 1998-2006, 10% of all infectious-disease hospitalizations were related to cellulitis[4]

- 22-49% of patients who have cellulitis report at least one previous episode[4]

- Recurrences, typically in the same location, occur approximately 14% of cellulitis cases within 1 year and in 45% of cases within 3 years[4]N

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Typical symptoms include acute poorly demarcated and spreading erythema along with pain, swelling, and warmth of the lower extremity but can occur on any area of skin or underlying subcutaneous tissue.[3][4] Additional symptoms may include fever, nausea, vomiting, and rigors.[4][6] Other features include proximal dilated and edematous skin lymphatics and bulla formation. Cellulitis predominantly has a unilateral presentation, most commonly in the lower extremity.[4]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Diabetes Mellitus is one of most common comorbidities among those hospitalized for acute bacterial infections including cellulitis. Following a cellulitis infection, those with diabetes require a longer course of antibiotic therapy and are more likely to have an outpatient follow-up visit.[7]

Lymphatic flow changes can predispose individuals to a cutaneous infection. Examples of co-morbidities that result in lymphatic flow changes include peripheral vascular disease, liposuction, radiation therapy, lymph node dissection, and lymphedema.[8]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Cephalexin, Dicloxacillin, Penicillin VK, Amoxicillin, and Clindamycin are typical Antistreptococcal Antimicrobial agents for the treatment of typical cellulitis that is considered mild and does not show signs of systemic involvement.[4]

Table 1 indicates which medications would be appropriate based on the severity of symptoms and the risk of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

| Clinical Presentation | Appropriate Antibiotic Treatment |

|---|---|

| Routine Cellulitis with low suspicion of MRSA | Dicloxacillin, Cephalexin, Nafcillin, or Cefazolin |

| High suspicion of MRSA or Penicillin allergy | Doxycyline, Clindamyciin, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| High suspicion of MRSA with signs and symptoms of severe infection or patient did not respond to intitial routine treatment | Vancomycin♦, Linezolid |

♦Vancomycin is the preferred treatment for MRSA[4]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Cultures are typically not beneficial in making a cellulitis diagnosis. It is most commonly diagnosed by history and physical examination alone. Certain laboratory tests can indicate the presence of infection, but are not specific to cellulitis alone. Elevated white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are the most common laboratory results in people with cellulitis, though the prevalence of these results varies widely on a case by case basis

Imaging studies can identify more severe infections to differentiate from cellulitis, but are not a reliable diagnostic tool for cellulitis itself.[4]

Identification of the cause of the infection through blood, needle aspiration or punch biopsy are not recommended unless the patient has a complication or abnormal exposure history. This would include immunosuppressants, a diagnosis of chronic liver disease, aquatic soft tissue injury, animal and human bites, or being in contact with various bacterias.[4]

If a biopsy and culture are warranted, a histopathologic evaluation will be performed on the sample. Hematoxylin-and-eosin and certain stainings for organisms, bacteria, fungi, and microbacteria will be included.[9]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

Cellulitis can be caused by various organisms but most commonly by Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus.[10] The organisms may enter the body after a cut, bite, or wound that compromises the skin or may enter through microscopic changes in the skin. They enter the dermis and multiply to cause cellulitis.

Studies show lymphedema is a major risk factor for the development of cellulitis. There is known to be a link between the two, but it is not known which of the two comes first. Patients with lymphedema or chronic edema are more prone to infection due to damage to lymphatic vessels and immune deficiency in that area. Cellulitis on the other hand, can cause damage to the lymphatics and the development of lymphedema.[8]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Cellulitis can be found anywhere on the skin, and can cause systemic issues in those areas. Locally, cellulitis often results in significant tissue damage in the involved area.[4] Cellulitis can spread systemically through the lymphatics and blood stream, which can lead to further complications.[1] If cellulitis does spread systemically through one of these systems, it can cause flu-like symptoms such as fever, rigors, nausea, and vomiting.[6][8] Though rare, there is a risk for severe sepsis, gangrene, or necrotizing fasciitis if cellulitis spreads systemically and is left untreated.[6]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Currently, there are no published national guidelines for the treatment of cellulitis. Although there are no national guidelines, there are two classification systems based on expert opinion that may be used. The Eron Classification system is the most widely used and is described in Table 2[11]. A more recent classification system, The Dundee Classification, was released in 2010. Table 3 compares these two classification systems based on strength of evidence, validation, and criteria.[11]

Most common management of the infection is administration of antibiotics. In more severe cases of cellulitis, intravenous antibiotics can be used.[9] Elevation and compression of the affected area promotes drainage of edema and can reduce inflammation, speeding up recovery.[9]

For those with recurrent cellulitis, prophylactic antibiotic therapy is an option. Recent studies show that antibiotic prophylaxis substantially reduced the number or recurrences experienced by patients while actively taking the medication. Although there is reduction during the antibiotic therapy, there is no evidence of persistent protect effect after it has ceased.[2]

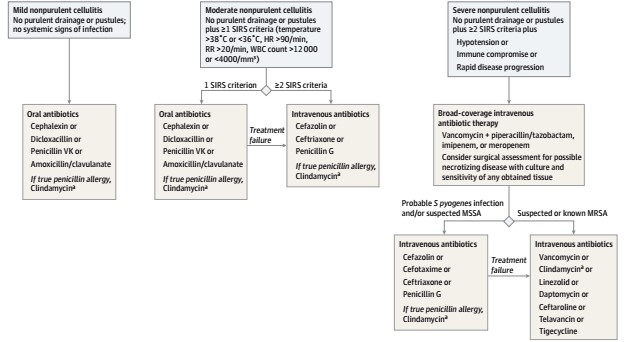

Below is a treatment algorithm for Non-purulent Cellulitis, as described by Raff et. al.[4]

| Class | Systemic toxicity | Comorbidities | Oral v intravenous antibiotics | Outpatient v hospital admission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No sign | None | Oral | Outpatient |

| II | May or may not have systemic illness | Peripheral vascular disease,

obesity, venous insufficiency |

Intravenous | Hospital admission for 48 hours then

outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy |

| III | Significant systemic toxicity—confusion,

tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypotension |

Unstable | Intravenous | Hospital |

| IV | Sepsis syndrome/necrotizing fasciitis | Unstable | Intravenous with or without surgical debridement | Hospital |

| Parameter | Eron (2003) | Dundee (2010) |

|---|---|---|

| Strength of evidence | Expert opinion | Retrospective study of 205 consecutive patients |

| Incorporated into guidelines? | CREST and NHS acute trusts | NA |

| Validated? | Yes | Yes |

| Criteria | Comorbidities including obesity and peripheral vascular

disease |

The importance of comorbidities |

| Systemic toxicity: pyrexia (>38ºc), hypotension, tachypnoea,

and tachycardia |

Obesity and peripheral vascular disease not counted towards hospital

admission | |

| Up to date definition of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) | ||

| Standardised and validated early warning scores |

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

While there is lack of evidence that discusses specific physical therapy interventions for cellulitis, therapists should be aware of the signs and symptoms in order to refer the patient appropriately. Physical therapists should have awareness of risk factors and various causes of cellulitis, in addition to signs and symptoms.

According to some references, there are some modalities that physical therapists can use for a patient with cellulitis. Rest and elevation of the affected limb is important and can help alleviate pain. The application of cool, wet, sterile bandages is also recommended for pain relief, and ice can be used as well. Massage to promote lymphatic drainage, may help prevent cellulitis, particularly when used in conjunction with compression and exercise. However, it should not be used during an active cellulitis infection.[12]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Common differential diagnoses for Cellulitis include Deep Vein Thrombosis, Dermatitis, and Erythema Migrans. A description of these and additional diagnoses are described in Table 4[5]

A diagnosis other than Cellulitis can be due to infectious, inflammatory, vascular or neoplastic conditions. These are discussed in Table 5.[4]

| Erythema Migrans | Commonly caused by tick bite; presents as “bullseye” rash on skin; can be due to recent travel to NE, NW, or Upper Midwest US, and certain parts of Canada, Europe, and Asia |

| Deep Vein Thrombosis | Suspected if certain risk factors present (examples include: family history, active cancer treatment), positive compression ultrasound test, D-dimer test results would be elevated |

| Stasis Dermatitis | Would present bilaterally; may have hyperpigmentation changes; commonly seen over medial malleoli; responds well to compression, elevation, and steroid use |

| Contact Dermatitis | Would present with pruritus and noticeable skin reaction; would likely have a report of exposure to a skin irritant |

| Infectious | Herpes zoster virus; Herpes simplex; skin ulcers |

| Inflammatory | Gout; drug reactions; angioedema; acute bursitis |

| Vascular | Lymphedema; hematoma; thrombophlebitis |

| Neoplastic (uncommon) | Lymphoma; Leukemia; Paget disease of the breast; inflammatory carcinoma of the breast |

| Other | Insect bites; adverse reaction to implant (examples include metal, mesh, or silicone) |

Resources[edit | edit source]

A video link by dermatologist Dr. Noah Craft MD, PhD, DTMH discusses Cellulitis from the provider point of view and includes case studies, differential diagnosis, and treatment approaches.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Medscape. Cellulitis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214222-overview (accessed 27 Feb 2017).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mason JM, Thomas KS, Crook AM, Foster KA, Chalmers JR, et al. Prophylactic Antibiotics to Prevent Cellulitis of the Leg: Economic Analysis of the PATCH I and II Trials. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e82694 http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0082694 (accessed 28 Feb 2017).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tsai C-YL, Calvin MK, Chung C, Susan Shin-Jung L, Yao-Shen C, Hung C. Development of a prediction model for bacteremia in hospitalized adults with cellulitis to aid in the efficient use of blood cultures: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(1):581.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: A Review. JAMA. 2016;316(3):325-37. http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/935437/ (accessed 27 Feb 2017).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bailey E, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: Diagnosis and Management. Dermatologic Therapy. 2011;24:229–39.http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1529-8019.2011.01398.x/full (accessed 15 Mar 2017).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Kilburn SA, Featherstone P, Higgins B, Brindle R. Interventions for cellulitis and erysipelas. (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(6):CD004299.

- ↑ Jenkins TC. Comparison of the Microbiology and Antibiotic Treatment among Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients Hospitalized for Cellulitis or Cutaneous Abscess. J Hosp Med. 9ADADDec12;:788–94.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4256165/ (accessed 28 Feb 2017).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Riches K, Keeley V. Cellulitis in patients with chronic oedema. Nursing & Residential Care [serial on the Internet]. (2012, Mar), [cited March 31, 2017]; 14(3): 122-127. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, Lahr BD, Martinez J, Mirzoyev SA, Baddour LM. A predictive model of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a population-based cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):709-715 http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/412163 (accessed 15 March 2017)

- ↑ Phoenix G, Das S, Joshi M. Diagnosis and management of cellulitis. BMJ [Internet]. 2012Jul [cited 2017Mar20];345(aug07 2):38–42. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/187604?path=/bmj/345/7869/Clinical_Review.full.pdffckLRMedscape. Cellulitis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214222-overview (accessed 27 Feb 2017).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Phoenix G, Das S, Joshi M. Diagnosis and management of cellulitis. BMJ [Internet]. 2012Jul [cited 2017Mar20];345(aug07 2):38–42. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/187604?path=/bmj/345/7869/Clinical_Review.full.pdffckLRMedscape. Cellulitis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214222-overview (accessed 27 Feb 2017).

- ↑ University of Maryland Medical Center. http://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/condition/cellulitis (accessed 25 March 2017).