Celiac Disease (Coeliac Disease)

Original Editors - Brandon Fowler from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Brandon Fowler, Zeina Grifoni, Admin, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Lucinda hampton, Vidya Acharya, Dave Pariser, 127.0.0.1, Rishika Babburu, Elaine Lonnemann, Wendy Walker and WikiSysop

One Page Owner - Vidya Acharya as part of the One Page Project

Definition[edit | edit source]

Celiac disease is a multi-system autoimmune disorder in which the body mounts an inflammatory response to the presence of gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, rye, triticale (a hybrid of wheat and rye), malt, and brewer’s yeast[1], in genetically susceptible persons. Exposure to gluten in susceptible persons leads to enteropathy (damage to the small intestine)resulting in impairment of the mucosal surface of the small intestine and, consequently, poor absorption of nutrients.[2] [3] Left untreated, Celiac Disease can lead to intestinal lymphoma and increased mortality. [4]It was first reported by Samuel Gee in 1888, however, the role of gluten in the pathology was only identified in 1953. Celiac disease is also called gluten sensitive enteropathy. Celiac disease is associated with other autoimmune disorders including autoimmune thyroid disease and type one diabetes.[3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of Celiac disease is growing worldwide with 40-60 million people affected [5]and is currently estimated to be from 1/70 in most countries with 70% of reported cases occurring in women.[6] It was originally thought that Celiac Disease affects primarily caucasians of northern European descent, however more recent studies have demonstrated worldwide prevalence including North America, South America, Asia, India, and Africa [7] with the highest preevalence of 5.6 % , found in the Western Sahara in people of Saharawi of Arab-Berber descent. [5] Celiac Disease is commonly manifested in infancy or childhood, with the introduction of food products containing gluten.[3] However, it is not uncommon for the disease to go undetected until much later in life. The average age of diagnosis of celiac disease in the United States is around age 50. Increased prevalence may be due to the improvement in the ability to detect the disease both serologically and through biopsy in addition to more frequent genetic testing and early correlation of symptomatic individuals to the disease. Environmental factors may increase the risk and prevalence of the disease such as increased gluten exposure at a young age, increased presence of gluten in processed foods, and exposure to antibiotics or other factors that have the potential to change the overall gut biome.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Primary symptoms often include abdominal bloating (with significant distention often noted in children), diarrhea, chronic diarrhea, abdominal cramping, bloating, indigestion, weight loss, gastric ulceration, and reduced fertility for both men and women.[3][8] Secondary symptoms, due to malnutrition, include fatigue, depression, nausea, muscle atrophy, changes in bone mineral density, and joint pain. If the problem persists long enough without treatment, excessive nocturnal reabsorption of intestinal fluids can occur, causing nocturia (excessive night time urination). In addition to nocturia, if the condition is severe enough, a gluten-related skin disorder may also be present (dermatitis herpetiformis)[9]. Celiac Disease is commonly found in adjunct with Diabetes, Down Syndrome, Turner Syndrome, William Syndrome, Sjogren Syndrome, autoimmune thyroid disorder, autoimmune hepatitis, congenital heart defects, and Addison Disease.[3][10]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Co-morbidities for Celiac Disease include dermatitis herpetiformis, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, dehydration, hypotension, lymphoma, bowel cancer, microscopic colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and osteopenia/osteoporosis.[3][9]

Medications[edit | edit source]

There is currently no treatment for Celiac Disease except the avoidance of gluten in the diet. This proves to be increasingly difficult as gluten is found in many commercially produced foods and there is high risk of cross contamination in production and packaging facilities, restaurants, and homes. In addition, substitution of foods not containing gluten for familiar gluten containing foods, such as gluten free breads, crackers, pastries, lack the vitamins and minerals that are naturally found in their gluten containing counterparts, predisposing those with Celiac disease for nutritional deficiency.[11] Over-the-counter supplements may be prescribed in order to meet personal daily nutritional needs. Hematinics may also be prescribed to stimulate red blood cell volume and to increase hemoglobin availability in order to address blood volume deficiencies. If primary means of treatment prove to be ineffective, corticosteroids can be utilized in order to reduce the inflammatory processes present in the small intestine. [3]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Serologic marker testing[edit | edit source]

Serologic marker testing of the Anti-tissue transglutaminase Immunoglobulin A and Immunoglobulin G antibodies (tTg-IgA and tTG-IgG) has become the first-line test to confirm a diagnosis of Celiac disease. [12].[13] Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody and anti-endomysial antibody (an antibody against an intestinal connective tissue protein) are both tested and each have sensitivity and specificity of greater than 90%.[3][14]The limitation of this test is that the presence of gluten in the diet is necessary to confirm diagnosis and may not be positive in persons who have already eliminated gluten from the diet.[12]

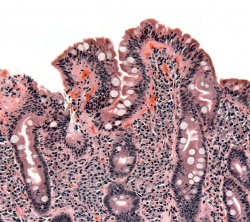

Biopsy[edit | edit source]

A biopsy from the second portion of the duodenum to verify the presence of pathology in the region, it often used to confirm the diagnosis of Celiac Disease. This in combination with positive serologic results can definitively indicate the presence of Celiac Disease. An abnormal biopsy presents with either histologic changes to surrounding epithelial tissue or by the presence of villous atrophy.

Blood work[edit | edit source]

There are several blood tests that are important to consider in celiac disease.

A complete blood count (CBC) to test for iron deficiency anemia or folate deficiency anemia is also another common test implemented in the diagnosis and treatment of Celiac Disease[3]. Normal Hematocrit levels include the following values: 36%-40% for children, 40%-50% for males, and 38%-47% for females. Normal Hemoglobin values are indicated as the following: children 11-13 g/dl, adult males 13-18 g/dl, and adult females 12-16 g/dl. Normal platelet levels are between a count of 150,000-450,000 per serum sample[13].

Vitamin B12 testing is indicated as many gluten free foods do not contain high values of B12 and the effects of Celiac Disease on small intestine may prevent its ability to absorb and assimilate B12 from ingested foods. Normal levels of B12 are essential for normal blood formation, the production of Myelin in the nervous system, and resultant neurological function.[15]Range of vitamin B12 levels can vary greatly, but neurological manifestations have been seen at levels of below 350 pg/ml.[16][17][18]

A complete metabolic profile (BMP) is often implemented in the diagnosis of Celiac disease to ascertain information about blood electrolyte chemistry and liver enzymes. This lab profile reveals information pertaining to pathology concerning dehydration and malabsorption by the small intestine, liver enzyme abnormalities and blood protein levels which may be abnormal in some cases of celiac diseases.[3]

Normal values are as follows:[19]

- Sodium: 135-145 mEq/L

- Chlorine: 96-105 mEq/L

- Blood urea nitrogen 10-25 mEq/L

- Potassium: 3.5-5.2 mEq/L

- Carbon Dioxide: 22-27 mEq/L

- Creatinine: 0.8-1.2 mEq/L

- Glucose: and 70-120 mEq/L (note: the unit of mEq/L is milliequivalent of indicated compound per liter of total serum sample)[13]

- ALT: 7 to 55 units per liter (U/L)

- AST: 8-48 U/L

- ALP: 40-129 U/L

- Albumin: 3.5-5.0 grams per deciliter (g/dl)

- Total protein:6.3-7.9 g/dl

- Bilirubin. 0.1 to 1.2 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL)

The d-xylose absorption test can also be performed to help differentiate intestinal mucosal disease from pancreatic disease[20]. This test reveals information about the integrity of the intestinal mucosal lining. Abnormal absorption is indicated if serum d‑xylose is less than 20 mg/dL or less than 4 g of d-xylose is present in a urine sample. This test is 91% sensitive and specific for detecting small intestine malabsorption.[20]

Other tests[edit | edit source]

Other tests include:

- Barium Xray test to detect the presence of malabsorption along the gastrointestinal tract

- Direct stool sample analysis of fat content can also be implemented to detect the presence of steatorrhea (abnormally high-fat content contained within expelled fecal matter). Fecal fat greater than 7 grams per day is considered abnormal.[3][21]

Causes/Mechanism[edit | edit source]

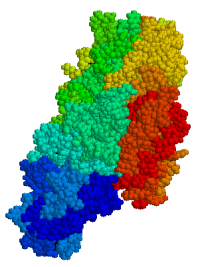

Although there is no direct known cause for Celiac disease and no consistent trigger for the immune response in affected individuals, researchers believe changes in genes, primarily but not limited to the HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, predispose a person to Celiac Disease.[8] In people with the genetic propensity for a gluten reaction, estimated to be between 10 and 15% in those with a first degree relative with Celiac Disease, [4]the ingestion of foods containing gluten stimulates gluten sensitive T-cells in the small intestine. The T-cells trigger an inflammatory process in the small intestine which changes the histological makeup of the cells that line the lumen of the small intestine and it causes the villi (hair like projections within the lumen of the small intestine involved in nutrient absorption) to atrophy and eventually to be destroyed.[9]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

The small intestine is the primary organ targeted for systemic involvement of Celiac Disease. Abdominal distention, abdominal cramping, nausea, and indigestion are all direct results of systemic involvement of Celiac Disease affecting the small intestine.[9] Malabsorption of ingested nutrients and changes in dietary habits however, can manifest dysfunction throughout the entire systemic system.[9] Changes in bowel and bladder habits are commonly associated with the presence of Celiac Disease. Explosive acute diarrhea, chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea (increased fraction of fecal fat), and nocturia (increased urination at night) are among the symptoms that can occur pertaining to changes in bowel and bladder function related to Celiac Disease.[9] Changes in blood volume can result from malabsorption problems of the small intestine. Hypotension and anemia can often manifest from pathologic changes of blood volume related to malabsorption problems.[9] Fatigue (both central command and peripheral) and an ability to focus conscious attention can result from the brain and entire body not receiving daily nutritional requirements from blocked absorption at the small intestine. In some cases of Celiac Disease, hypertension has also been reported[22].The issues related to blood volume can vary from person to person, depending on family history, dietary habits, and lifestyle choices of the indvidual. An associated reaction of the epidermis may also be involved. A skin rash known as Dermatitis Herpetiformis can form commonly at the buttocks, knees, or elbows as a direct consequence of Celiac Disease.[9] Other systemic conditions such as polyneuropathy, dilatative cardiomyopathy, psoriasis, and vasculitis may also result from malabsorption.[9]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The primary treatment for Celiac Disease is maintaining a life long regimen of a gluten free diet.[3]and should be managed by a registered dietitian nutritionist and physician with expertise in the management of Celiac Disease.[10] [4]Nutritional supplements are also commonly used in adjunct to maintaining a gluten free diet.[3][10] This is done in order to make up for nutritional deficiencies that are often present when following a gluten free dietary regimen. The nutritional insufficiencies may vary depending on the dietary habits of the individual. Corticosteroid treatments may also be utilized if the traditional means of treating Celiac Disease are unsuccessful.[3]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Although Celiac Disease is derived solely from pathology involving the enteric system, physical therapy can be beneficial in order to minimize and treat secondary conditions that may accompany Celiac Disease.

Such conditions include:

- Joint pain

- Edema

- Muscle atrophy and weakness

- Osteoporosis/osteopenia.[23]

- Chronic fatigue

- Cerebellar ataxia

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic Lupus erythematosus

- Peripheral axonal neuropathy

- Energy management

- Overall physical fitness and weight management

- Patient education and resources for dietary recommendations, lifestyle choices, appropriate rest intervals, and community resources

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Below is a list of conditions that should be considered prior to the diagnosis of Celiac Disease. A complete medical history (both subjective and objective), a thorough clinical exam, and extensive laboratory testing should be implemented in the differential diagnosis of Celiac Disease.[3][8][9][10][24]In some cases, these syndromes may present in conjunction with Celiac Disease making the full diagnosis more difficult.

- Food allergy

- Lactose intolerance condition

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Lymphoma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Diverticulitis

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Intestinal infections

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Crohn's disease

- Tropical sprue

- Pancreatic insufficiencies

- Gastroenteritis(viral or bacterial)

- Hypocalcemia

- Hyperkalemia

- Girdiasis

- Colorectal cancer

- Eczema (when Dermatitis Herpetiformis condition present)

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

- Celiac Disease Symptoms in a Female Collegiate Tennis Player: A Case Report[13][13][13][13][12][12][9][9][9][9][9][9]

Resources[edit | edit source]

1. Link to comprehensive list of foods containing gluten [24][24][24][24][23][19][19][17][16][16][15][15][15][15][15][15][15][15][14][14][14][14][14][14][14][13][13]

2.Celiac Sprue Association Sponsored Gluten-free recipes and tips for cooking gluten free: http://www.csaceliacs.org/recipes.php[25][25][25][25][24][20][20][18][17][17][16][16][16][16][16][16][16][16][15][15][15][15][15][15][15][14][14]

3.Link to Nationwide contacts for Celiac Disease support groups by state[16][16][16][16][15][15]

4. A 2020 discussion on Celiac Disease and non-Celiac gluten intolerance from Mayo Clinic Radio: definition, challenges of the disease, and treatment.

5. Gluten Sensitivity: a disease of the brain: Professor Marios Hadjivassiliou 2021, Sheffield Gastroentereology. A lecture on the effects of gluten exposure on the brain.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Sources of Gluten | Celiac Disease Foundation." https://celiac.org/gluten-free-living/what-is-gluten/sources-of-gluten/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2022.

- ↑ Parzanese I, Qehajaj D, Patrinicola F, Aralica M, Chiriva-Internati M, Stifter S, Elli L, Grizzi F. Celiac disease: From pathophysiology to treatment. World journal of gastrointestinal pathophysiology. 2017 May 15;8(2):27.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Ruiz,Atenodoro R. Jr. Celiac Sprue.Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec02/ch017/ch017d.html?qt=celiac%20disease&alt=sh. (Accessed 1 March 2010).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac Disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jan 7;172(1):ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070. PMID: 31905394; PMCID: PMC7707153.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Makharia, GK, Chauhan, A, Singh, P, Ahuja, V. Epidemiology of coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022; 56(Suppl. 1): 3- 17.

- ↑ Gujral N, Freeman HJ, Thomson AB. Celiac disease: prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Nov 14;18(42):6036-59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6036. PMID: 23155333; PMCID: PMC3496881.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:1 - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mayo Clinic. Celiac Disease. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/celiac-disease/DS00319 (Accessed 1 March 2010).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Goodman Catherine C., Fuller Kenda S. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2009. p848-851.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Fasano Alessio,Catassi Carlo. Current Approaches to Diagnosis and Treatment of Celiac Disease: An Evolving Spectrum. Gastroenterology 2001;120:636–651. http://medschool.umaryland.edu/celiac/documents/celiacgastro.pdf (Accessed 1 March 2010).

- ↑ Makharia GK. Current and emerging therapy for celiac disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2014 Mar 24;1:6. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2014.00006. PMID: 25705619; PMCID: PMC4335393.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lebwohl, Benjamin, Rubio-Tapia, Alberto. Epidemiology, Presentation, and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease. Reviews and Perspectives Reviews in Basic and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021January 01;160(1):63-75.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Mook, Kenneth A MD PhD. Personal communication: Lecture "Interpretation and Application of Common Labwork."Bellarmine University, Louisville Ky. 26 January 2009.

- ↑ Schuppan, D., Dietrich, W, Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations of celiac disease in adults [Internet].2022 [cited 24 November 2022]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-pathogenesis-and-clinical-manifestations-of-celiac-disease-in-adults?search=celiac%20disease&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1998. 9, Vitamin B12. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114302/

- ↑ Conclusions of a WHO technical consultation on folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies. de Benoist B. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/15648265080292S129 Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29:238–244.

- ↑ Cobalamin: a critical vitamin in the elderly. Wolters M, Ströhle A, Hahn A. Prev Med. 2004;39:1256–1266.

- ↑ Jatoi S, Hafeez A, Riaz SU, Ali A, Ghauri MI, Zehra M. Low Vitamin B12 Levels: An Underestimated Cause Of Minimal Cognitive Impairment And Dementia. Cureus. 2020 Feb 13;12(2):e6976. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6976. PMID: 32206454; PMCID: PMC7077099.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic.Liver Function Tests. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/liver-function-tests/about/pac-20394595 (accessed November 24, 2022)

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ruiz,Atenodoro R. Jr. Introduction to Malabsorption Syndrome.Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec02/ch017/ch017a.html (Accessed 1 March 2010).

- ↑ Johnson, Larry E. Vitamin B12. Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec01/ch004/ch004i.html#sec01-ch004-ch004j-395 (Accessed 2 March 2010).

- ↑ Zamani Farhad, Et al. Celiac disease as a potential cause of idopathic portal hypertension: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2009; 3:68. http://jmedicalcasereports.com/content/3/1/68 (Accessed 3 March 2010)

- ↑ Fuchs, V., Kurppa, K., Huhtala, H., Collin, P., Mäki, M., & Kaukinen, K. (2014). Factors associated with long diagnostic delay in celiac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 1–7.

- ↑ Goodman Catherine C., Snyder Teresa E. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2007. p366-408.

- ↑ Silvester JA, Therrien A, Kelly CP. Celiac Disease: Fallacies and Facts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jun 1;116(6):1148-1155. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001218. PMID: 33767109; PMCID: PMC8462980.