Case Study: Exercise in MS

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Kim Jackson, Rucha Gadgil, Evan Thomas and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Treating therapist & author[edit | edit source]

This case study was completed by neurological physiotherapist Megan Knowles-Eade. She has given full permission for this to be published on Physiopedia.

The individual chosen for the case study (CS), pictured opposite, has also given his permission for clinical details and all photographs to be published on Physiopedia.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The person chosen for this case study (CS) was a 48 year old male diagnosed with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (MS) 18 years ago. Due to the ceasing of relapses and a gradual deterioration of symptoms and physical presentation the CS was diagnosed with Secondary Progressive MS 8 years ago.

MS is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory condition of the central nervous system (CNS). It affects approximately 100,000 people in the UK (NICE 2014). The progression of the disease is unpredictable but can have a severe impact on functioning and quality of life. MS affects quality rather than duration of life (Buckley 2008[1]). MS presents with varying signs and symptoms. The CS had typical disease symptoms of weakness in lower limbs and upper limbs, spasms and areas of increased tone, bladder and bowel dysfunction and most significantly, fatigue.

Clinical Details[edit | edit source]

The CS was a full time wheelchair user requiring assistance from his wife for all activities of daily living (ADLS). He had recently given up driving his adapted vehicle due to fatigue levels and worries about reaction times. The CS had been fully dependent on a wheelchair for the last 10 years, although can transfer through a pull up into standing and a fast pivot to get onto his stair lift.

The CS had taken part in no regular structured exercise apart from weekly Physiotherapy sessions. These sessions involved elements of exercise e.g. assisted stands, active-assisted lower limb activation, sitting balance and posture work. The CS had, over recent years, felt a significant deterioration in his physical presentation and on occasions feels low in mood.

Last year the CS suffered from a chest infection which took a month to clear and three doses of antibiotics. MS can cause weakness to the respiratory muscles with can lead to inefficient ventilation and cough, predisposing them to chest infections (Buyse et al. 1997[2]). The CS was motivated to try for new goals to maintain his current level of ability and physical presentation but felt intimidated by a gym setting. It was thought by the CS that he would not be able to partake in this environment due to his level of disability.

Barriers to exercise in LTNC[edit | edit source]

Lack of activity is a serious health concern and yet it is estimated that 1 billion people with a disability report barriers to carrying out exercise[3]. Lack of appropriate exercise facilities and negative attitudes towards exercise are common barriers preventing people with Long Term Neurological Conditions (LTNC) seeking out regular exercise[3].

Components of Physical Fitness[edit | edit source]

Physical fitness has seven components; aerobic power, aerobic endurance, metabolic function, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility and balance and coordination (Buckley 2008[1]). Inactivity, sedentary lifestyle and neurological signs and symptoms impact heavily on all of these components. It was hypothesised that the CS had a decreased ability in all of the components due to being wheelchair bound for the past eight years and having not taken part in any regular, structured activity.

Fatigue issues in MS[edit | edit source]

The CS had limited his ADLs due to his levels of fatigue. Fatigue is the most debilitating symptom of MS and impacts on all aspects of functioning[4]. The CS reported this as his most problematic symptom. Until recent years it was thought that exercise exacerbated fatigue and it was advised to limit physical activities. Exercise is now more understood, and in the NICE guidelines for “Management of Multiple Sclerosis in primary and secondary care” (2014)[5] exercise training is the most recommended non pharmacological intervention for the management of MS.

Risk Assessment[edit | edit source]

Using the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) risk stratification it was deemed that the CS was at “moderate risk” for exercise. This conclusion was based on his age (“over 45 years old”) and his “lack of regular activity”. A Physical Readiness for exercise questionnaire (PARQ) was filled out and indicated no risk for cardiac events during exercise (“No” for all 9 questions). Informed consent was given by the CS to take part in a four week structured exercise programme in a gym environment supported by a physiotherapist.

Methodology[edit | edit source]

The ASCM risk stratification of “Moderate risk” indicates the need to seek medical clearance before partaking in this project. Clearance was sought and gained from the CS General Practitioner deeming there to be “no medical reason why he cannot take part in supervised exercise in a gym setting”. A local adapted gym for people with disabilities was sought and the Personal Trainer at that gym contacted. An induction was arranged.

Goals & Outcome Measures:[edit | edit source]

| Goal | Outcome Measure |

|---|---|

| To take part in exercise outside the home without increasing fatigue levels preventing daily functioning | Fatigue Severity Scale [FSS] |

| To gain a beneficial hobby that can be sustained, without supervision of the author, on a weekly basis | Blood Pressure [BP]

Heart Rate [HR] Rating of Perceived Exertion on active cycle [RPE] |

| To improve function of right upper limb, in particular ease of putting seat-belt on, lifting lap-top from bed onto knees when sitting in bed, and operating the lightswitch when in bed. | Grip strength

Range of Movement [ROM] Subjective |

| To prevent/improve the ability to manage any respiratory complications | Peak Expiratory Flow Rate [PEFR]

Posture |

Outcome Measures on Initial Assessment.[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures were used and repeated before exercise commenced, at the middle point and on the last session.

- BP: On initial assessment the CS blood pressure readings were measuring consistently at the pre-hypertension stages ( 120-139/80-89) and in some cases at stage 1 hypertension (140-159/80-89), using the ACSM classification of blood pressure . Blood pressure readings were monitored before each session to ensure that exercise was safe to carry out. The frequency, intensity, type and time (FITT) guidelines for cardiovascular and resistance training for Stage 1 hypertension fall within those recommended for MS, therefore, the MS guidelines were utilised with special precautions to avoid heavy loads, heavy over head loads and isometric work (as per exercise prescription for Stage 1).

- FSS was used to measure fatigue. It is the suggested outcome measure for the energy and drive dimension of the ICF (WHO) for MS. This tool was chosen as it is a “simple and reliable instrument to assess and quantify fatigue” (Valko et al. 2008).

- Grip Strength: An electronic hand dynamometer was used to measure grip strength and goniometer to measure range of movement at the shoulder girdle, both recognised therapy tools for measuring these outcomes.

- Perceived exertion and effort was measured using the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (6-20 point scale) for cardiovascular exercise and the Modified Borg scale (0-10 point scale) for resistance exercise. Heart rate readings and subjective reported fatigue alone can be inaccurate as it is thought that up to 75% of MS sufferers may have autonomic dysfunction which can alter perceived exertion[6] (Morrison et al. 2008 ). However, RPE scores were found to be the same as people exercising without MS[6]. The CS HR and RPE scores were deemed as appropriate and accurate throughout the exercise programme.

- Lung Function. Aspects of the CS lung functioning were measured using a Spirometer. Peak Expiratory Flow rates were measures at the pre, mid and end point. Peak flow readings are significantly lowered in MS sufferers[7] and this was found in the CS.

- Active Range of Movement was measured in the right upper limb.

Exercise Programme[edit | edit source]

The exercise programme comprised both cardiovascular components and resistance training.

Passive and active-assisted stretches were carried out during and at the end of the session with the aid of the Physiotherapist.

The prescription was made under guidance the ACSM (2014)[8] recommendations for people with MS:

- To take part in cardiovascular activity 3-5 days a week within 40-70% of heart rate reserve (HRR) for 20-60 minutes per session.

- Resistance training should be carried out 2-3 days per week, within 60-80% of one repetition maximum (1RM). 1-2 sets with 8- 15 repetitions.

Due to the sedentary lifestyle that the CS had before beginning this project, lower ends of the guidelines were utilised for week one. The CS progression was based on the individuals’ tolerance, physiological and subjective positive responses to the exercise. Cardiovascular aspects of the programme were increased as per ASCM guidance[8] of 5-10 minutes every one-2 weeks for the first 4 weeks. Blood pressure, HR and RPEs were monitored closely throughout.

Cardiovascular weekly time progression:[edit | edit source]

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 |

| 32 minutes (including warm up and cool down) | 43 minutes (including warm up and cool down) | 51 minutes (including warm up and cool down) | 60 minutes (including warm up and cool down) |

An increase in time spent at the gym was planned for the programme progression along with increasing parameters for heart rate reserve percentage and repetitions and weight for resistance training. The CS found the Rowing machine to be the most physically demanding. This piece of machinery gave the highest heart rate and RPE reading. This machine was used to show progression through the MS exercise prescription percentages of heart rate reserve.

Planned progression of programme:[edit | edit source]

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | |

| CV | up to 116 BPM (40% HRR) | up to 126 BPM (50% HRR) | up to 135 BPM (60% HRR) | up to 144 BPM (70%HRR) |

| Resistance | RPE 5-6

2 set 8 reps |

RPE 5-6

2 sets 8 reps |

RPE 6-7

Increase weight |

RPE 7-8

Increase weight & reps |

Results[edit | edit source]

The results of this four week programme showed an improvement in all subjective and objective outcome measures used.

FSS results, PEFR, upper limb active ROM and RPE scores on active cycling showed the most dramatic improvements. Blood pressure readings slightly reduced over the four week period. Blood Pressure was monitored before each session to ensure safety to perform exercise. Readings varied between 140/90 to 135/85 (see Table 4). By week four the CS diastolic pressure was reading consistently at 85 mmHg. The CS still remains in the ‘Pre hypertensive’ range of blood pressure readings (ACSM) but the no further ‘Stage 1 hypertensive’ readings were recorded after the first session. It was assumed that this was a one off reading due to anxiety of preparing for exercise. Resting heart rate remained consistently at 80 beats per minute throughout this study. When exercising the maximum heart rate achieved was to 136 beats per minute and the CS RPE at this intensity was measured at “16-17; hard-very hard”. This was achieved in the last session of this exercise programme intervention whilst using the Rowing machine (see appendix 6b).

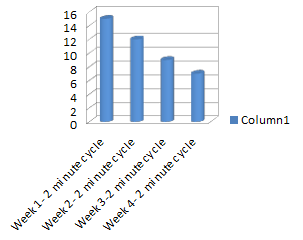

Graph 1 shows the Borg RPE on two minutes of active cycling without resistance. This was performed after the warm up at the first session of each week. The CS RPE reduced from a numerical value of “15- hard” in Week one to” 7-very very light” at the beginning of week four. In week one the CS completed one minute of active cycling and then required rest for 30 seconds before completing the second minute. The CS was able to complete two consecutive minutes for week two to week four without rest gradually becoming easier to perform throughout the weeks. In week one this two minute cycle was the only active cycling achieved in the session but by week four the CS performed 12 minutes on the cycle without rest. The cycle used was an assistive cycle (“MOTOmed”) that measures the symmetry in the lower limbs whilst pedalling. Equality of lower limb push was encouraged during cycling (see appendix 6a). By week four the CS could sustain an equal symmetry for 8 out of the 12 minutes, in contrast to week one which was heavily bias to the left lower limb for the duration of the cycle.

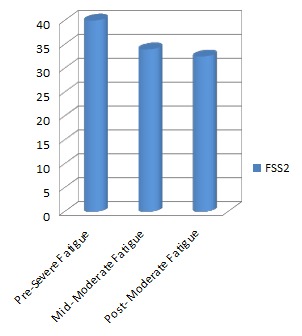

Peak Expiratory Flow Rates were measured using a Spirometer. Graph 3 plots the readings recorded showing a dramatic increase over the four weeks. The predicted PEFR for the CS height and age was 570 L/min. The CS at week one scored 100L/min or 18% of his predicted PEFR, 220L/min or 39% of his predicted PEFR at the mid point and 370 L/min or 65% of predicted rates at the end point. This rise correlated in the increase in exercise tolerance and intensity levels of the training programme (shown in Table 2). Increase in lung functioning followed a pattern of decreasing fatigue levels. Fatigue was reported by the CS as “among my three most disabling symptoms” on the Fatigue Severity Scale. This subjective questionnaire showed improvements from “severe” fatigue category (a score of >5) in week one to the “moderate” category (a score of 4) in week four (shown in graph 2). The Moderate category is scored at 4-4.9. The CS achieved the lowest end of the category by the end of the programme. The CS was surprised that his increased activities levels did not correlate with an increase in fatigue levels (Table 5).

Active range of movement of right upper limb in supine increased from 80 degrees to 100 degrees forward/flexion to elevation post programme and abduction from 45 degrees in week one to 85 degrees in week four. This had a functional impact on the CS ADLs shown in subjective reports (table 5). Although no specific work was carried out for grip strength this was also measured by the author. The dominant hand, grip strength increased by 6 Kgs over the four weeks. Interestingly the weaker side did not improve, showing perhaps the asymmetry in his physical upper limb abilities. When using the resistance machine, equipment that work in functional patterns of movement were selected. When using the “chest press” support under his weaker elbow was required to ensure quality of the movement (see appendix 6c). The CS enjoyed the resistance machines the most and was surprised by how strong he was. The CS led the increase in weights.

Lower limb clonus reduced throughout the intervention. The MS guidance for spasm and clonus is exercise and stretching (NICE 2014). The CS increased activity levels and the active stretching of his lower limb muscles. The CS also received passive stretches during and post session by a physiotherapist and was, therefore, stretching more frequently than his normal routine.

Adapted circuits were carried out in two of the four weeks. These were carried out in physiotherapy appointments, and posture was significantly improved after these clinic based sessions (see appendix 6d). They were restricted by time and were more difficult to complete as they involved assisted changes of position and transfers.

Result of BP readings, grip strength testing & active ROM goniometry:[edit | edit source]

| Outcomes Tested: | Pre | Mid | Post |

| Blood Pressure | 143/90 | 138/89 | 136/88 |

| Grip Strength [kgs] Right:

Left: |

20.2

29.7 |

20.7

29.9 |

20.8

33.2 |

| aROM right UL in supine Elevation:

Abduction: |

80

45 |

90

65 |

100

80 |

Subjective comments during exercise intervention:[edit | edit source]

| Subjective comments | |

| Week 2 | Increase in ease of bowel movements |

| Week 2 | Reduced clonus (noted in Physiotherapy session as well as noted by CS)

“Easier to move lower limbs onto foot plates without them spasming” |

| Week 3 | “In general it’s easier to move my right arm. I can pick the laptop up off the bed onto my knees without losing balance and I can reach up behind me to turn the light off.”

“I think it’s easier to put my seatbelt on”. “I am stronger than I thought”. |

| Week 1-4 | “I’m doing more but I’m not more tired”

“I don’t feel that I’ve reach my maximum yet. I think I can do more at the gym” |

| End | “I’ve really enjoyed it. I’m going to carry on going to the gym to see what I can do” |

Graph: 2 minute active cycle & Rating of Perceived Exertion [RPE][edit | edit source]

Graph: Fatigue Severity Scale[edit | edit source]

Discussion[edit | edit source]

The CS responded well to all aspects of the exercise programme. There were no detrimental effects noted. Research suggests that MS sufferers recover from sessions “normally” despite altered muscle performance[1]. Throughout the programme physiological responses were appropriate for the RPE scale noted. Although temperature regulation is an consideration for MS response to exercise this was not a problem for the CS. At the mid point there were improvements in all outcome measures and it was deemed safe to increase the amount of time spent exercising and the weight during resistance training. The CS showed physical adaptations similar to those without neurological disease. It could be predicted that the physical adaptations of further exercise may not be as dramatic as the first four weeks. The CS began from a very sedentary lifestyle to a huge increase in activity levels which is sure to have a significant effect of physiological response. It is thought that lack of physical activity is related to worsening of symptoms[9] and it might be inferred that the improvement in physical functioning could just be a result of a general increase in activity levels for the CS.

Resistance training weight increased more than was planned. This was due to the difficultly establishing 1 repetition maximum in the first week. The CS found the technique and machinery difficult at first, having never been to a gym before. It took until week two for the CS to feel completely comfortable with this. The resistance work was found to be most helpful in terms of function for the CS. It was found that working multiple muscle groups in functional patterns of movement have helped in ADLs. Rotational pull downs and chest press assisted in reaching for a seat belt, lifting and rotating for a laptop and maintenance of elbow extension for tasks.

The most significant changes were in lung function and fatigue levels. Wheelchair users take shallow breaths which reduces vital capacity[10]. The CS had a tendency towards slumping in his chair. Slumping impedes diaphragmatic movement and lowers lung functioning[10]. These factors will decrease ventilation and the amount of energy required for function. Expiratory muscle strength has been shown to be significantly reduced in MS patients which has a huge effect of general functioning[1]. Lowered PEFR is linked to poor expiratory muscle strength[11]. Poor expiratory muscle strength coupled with the secondary complications of being sat in a wheelchair for long periods of time e.g. Stiffness through the rib cage will cause decreased ventilation. Exercise increases aerobic capacity and respiratory muscle strength[4] which will aid fatigue resistance[12]. Increased Aerobic capacity is linked with improved functioning, quality of life and neuronal integrity in MS[12].

Although the results of this intervention are dramatic, it is limited by time. The four weeks of the study is too short a time to assume complete cause and effect. It does give an insight into the effect of exercise as a case study and the results have been similar to the literature for exercise effects on MS. Most pertinent and dramatic have been the decrease in fatigue and the increase in self efficacy reported. Health is “a state of complete physical mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity” (WHO 1948[13]). An increase in well being, self efficacy and the feeling of new accomplishments will have a positive impact on the CS.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bulkey, J. (2008). Exercise physiology in special populations: advances in sport and exercise science series. 1st edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier

- ↑ Buyse, B., Demedts, M., Meekers, J., Vandegaer, L., Rochette, F. and Kerkhofs, L. (1997). Respiratory dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a prospective analysis of 60 patients. European Respiratory Journal 10, 139-145

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rimmer, JH., Riley, B., Wang, E., Rauworth, A. and Jurkowski, J. (2004). Physical activity participation for people with disabilities: barriers and facilitators. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 26 (5), 419-425

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Latimer-cheung, AE., Pilutti, LA., Hicks, AL., Martin Ginis, KA., Fenuta, AM., MacKibbon, KA. and Motl, RW. (2013). Effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health-related quality of life among adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review to inform guideline development. Archive of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 9 (94), 1800-1828

- ↑ National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2014) Multiple sclerosis: management of multiple sclerosis in primary and secondary care NICE clinical guideline 186. Retrieved on 9th February 2015 from http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg186/resources/guidance-multiple-sclerosis-pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Morrison, E., Cooper, D., White, L., Larson, J., Leu, SY., Zaldivar, F. and Ng, AV. (2008). Ratings of perceived exertion in aerobic exercise in multiple sclerosis. Archive of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 89, 1570-1574

- ↑ Rasova, K., Brandejsky,P., Havrdova, E., Zalisova, M. and Rexova, P. (2005). Spiroergometric and spirometric parameters in patients with multiple sclerosis: are there any links between these parameters and fatigue, depression, neurological impairment, disability, handicap and quality of life in multiple sclerosis? Multiple Sclerosis 11, 213-221

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 ACSM. (2014). American college of sports medicine’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 9th edn. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

- ↑ Motl, RW., Arnett, PA., Smith, MM., Barwick, FH., Ahlstrom, B. and Stover, EJ. ( 2008). Worsening of symptoms is associated with lower activity levels in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis 14, 140-142

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Fang, L., Parthasarathy, S., Taylor, S., Pucci, D., Hendrix, R. and Makhsous, M. ( 2006). Effects of different sitting postures on lung capacity, expiratory flow and lumbar lordosis. Archive of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 87, 504-509

- ↑ Hough, A. (2001). Physiotherapy In Respiratory Care. 3rd edition. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Prakash, R., Snook, E., Motl, RW. and Kramer, A. (2009). Aerobic fitness is associated with gray matter volume and white matter integrity in multiple sclerosis. Brain Research 1341, 41-51

- ↑ World Health Organisation (1948) WHO definition of heath. Retrieved on the 9th February 2015 from http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html