Bone

Original Editors -

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Candace Goh, Admin, Shaimaa Eldib, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Wataru Okuyama, Robin Tacchetti, George Prudden, Claire Knott, Manisha Shrestha, Khloud Shreif, Tony Lowe, Stephanie Geeurickx, WikiSysop, Joao Costa and Sai Kripa

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Bones are connected to each other to form the human skeleton - the framework of living tissue that grows, repairs, and renews itself. Under the right conditions, bone tissue undergoes a process of mineralization, formed by collagen matrix and hardened by deposited calcium. Bone tissue (osseous tissue) differs greatly from other tissues in the body. Bone is hard and many of its functions depend on that characteristic hardness.[1]

Structure[edit | edit source]

Gross anatomy[edit | edit source]

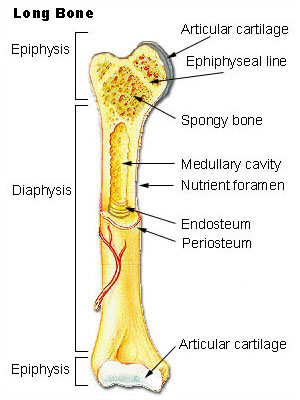

A long bone has two parts: the diaphysis and the epiphysis. The diaphysis is the tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. The hollow region in the diaphysis is called the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow marrow. The walls of the diaphysis are composed of dense and hard compact bone.[2]

Individual bone structure[edit | edit source]

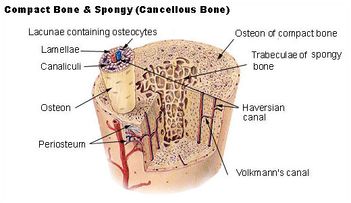

Two types of bone tissue are present - Compact/cortical bone and cancellous/spongy bone.

- Compact/cortical bone - Makes up outer part of bone. Rigid, dense, highly organised bone tissue, arranged in haversian systems which are microscopic cylinders of bone matrix with osteocytes in concentric rings around central haversian canals.

- Cancellous/spongy bone - Makes up inner part of bone. More elastic and porous, storage of red bone marrow. Osteocytes, matrix and blood vessels are not arranged in haversian systems.

Cellular structure[edit | edit source]

- Osteoblasts - produce matrix (osteoid), build up bone tissue

- Osteoclasts - secretes acids and enzymes to breakdown bone tissue

- Osteocytes - maintain bone tissue by mineralising osteoid

Molecular structure[edit | edit source]

Approximately 20% of in vivo bone is water. Of the dry bone mass, 60-70% of is bone mineral in the form of small crystals and the rest is collagen. The composition of the mineral component is hydroxyapatite Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 and collagen is the main fibrous protein of the human body.

Functions[edit | edit source]

Mechanical[edit | edit source]

- Protect internal organs

- Give shape and support to the body

- Movement

Synthetic[edit | edit source]

- Manufactures blood cells from the bone marrow (haematopoiesis)

Metabolic[edit | edit source]

- Mineral storage

- Fat storage

- Role in acid-base balance

Remodelling[edit | edit source]

Purpose[edit | edit source]

- To allow bone to ordinarily adjust strength in proportion to the degree of bone stress. When subjected to heavy loads, bones will consequently thicken.

- To rearrange shape of bone for proper support of mechanical forces in accordance with stress patterns.

- To replace old bone which may be brittle/weak in order to maintain toughness of bone. New organic matrix is needed as the old organic matrix degenerates.

Calcium homeostasis/balance must exist between osteoclasts and osteoblasts activity[edit | edit source]

- If too much new tissue is formed, the bones become abnormally large and thick (acromegaly)

- Excessive loss of calcium weakens the bones, as occurs in osteoporosis

Repair[edit | edit source]

- The osteoclasts function to remove fragments of dead or damaged bone by dissolving and reabsorbing calcium salts of bone matrix. Like a building that has just collapsed, the rubble must be removed before reconstruction can take place. Osteoblasts are activated to knit the broken ends of bone together.

Bone Related Disorders[edit | edit source]

- Bone fractures

- Osteoporosis

- Osteoarthritis

- Osteomalacia

- Rickets

- Epiphyseal plate disorders