Body Awareness in Survivors of Trauma

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Jess Bell and Nupur Smit Shah

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Body awareness is an approach often used within rehabilitation for individuals with persistent / complex pain [1][2] and / or psychosomatic / psychiatric conditions,[3][4][5][6] that explores and uses the mind-body-(spirit) connection to develop a more positive experience of the body and self through reflection of our bodily experiences.[7][8]

Body awareness has been defined as a treatment directed towards an awareness of how the body is used in terms of body function, behaviour, and interaction with self and others,[9] and can be influenced by both our emotional regulation, which is is our ability to exert control over our emotional state and interoception, which is the perception of sensations from inside the body and includes the perception of physical sensations related to internal organ function such as heart beat, respiration, satiety, as well as the autonomic nervous system activity related to our emotions.[10]

Use of body awareness strategies and therapies aim to normalise and help restore breathing, posture, balance, and muscular tension, which are commonly experienced and visible in the movement behaviour of individuals who have experienced trauma or displacement.[9][11]

Barriers to Care[edit | edit source]

Access to healthcare is a complex concept. If services are available and there is an adequate supply of services, then the opportunity to obtain health care exists, and a population may 'have access' to services, but the services available must be relevant and effective if the population is to 'gain access to satisfactory health outcomes'. There are many factors that can influence a persons ability to receive care. Commonly reported barriers to health include logistical factors (distance to service, lack or cost of transport), affordability (of services, treatment, lack of insurance), and knowledge, attitudinal and cultural factors (including perceived need, fear, and lack of awareness about the service). The following barriers are just some of those that can significantly impact on healthcare access in the context of trauma.

Language Barriers[edit | edit source]

Research suggests that communication difficulties act as a critical barrier for displaced persons seeking health and social services.[12] The majority of displaced persons may not speak the language of the host country and have fear of and difficulty in expressing their medical symptoms in a second language.[13] Therefore, people with a language barrier are often unable to seek adequate medical attention without an interpreter or translator, which are not always widely available depending on the language of the person.[14] Even with interpreters, miscommunication can occur between individuals and rehabilitation professionals due to the lack of proficient medical interpreters, which may lead inappropriate and inadequate care.[12] Confusion might arise during a medical and rehabilitation consultations, which can result in feelings of alienation and mistrust, which may prevent the individual from seeking out future medical care.[15]

Cultural Barriers[edit | edit source]

Cultural competence is a defined as a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes and policies that come together in a group of people to work effectively in cross-cultural situations such as an evaluation of programs and services provided to immigrants and refugees. [16] The word 'culture' is the integrated pattern of learned human behavior that includes thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values and institutions of a social group. The word 'competence' implies having the capacity to function effectively as an individual and as an organization with the context of cultural beliefs and behaviours.[16]

Unfortunately, there is evidence to suggest that race and ethnicity can affect the way that both individuals report pain and also the way in which rehabilitation professionals interpret an individuals pain, with research suggesting that physicians were twice as likely to under-estimate a patient with black ethnicity’s pain in comparison to those patients of white ethnicity.

Rehabilitation professionals need to be aware of their own cultural identity, develop an understanding of cultural knowledge of common health beliefs and behaviours and ensure they display culturally-sensitive behaviours (e.g., empathy, trust, acceptance, respect) to improve therapeutic alliance and clinical outcomes.[17]

Understanding of Healthcare System[edit | edit source]

Lack of knowledge about how to navigate the complex health care system results in poor access to healthcare services. The limited information on accessing primary health care services and not knowing whom to ask or where to go for health care, can result in frustration. It can also prompt to seek help from inappropriate sources. The displaced persons may experience difficulties; for example, immediate access to GP (General Practitioner) in the host countries follows a protocol that involves an appointment and wait-listed approach. It is contrasting to their homeland, where they get to see the GP immediately. It can be confusing as the displaced persons may think condition might resolve by the time, they get an appointment. The problem with this approach is that it may prevent individuals with more severe illnesses from acquiring medical attention early in the disease process5.

Impacts of Trauma[edit | edit source]

Trauma "results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being"[18] It can also include second-hand experiences (e.g. an individual might not have experienced the trauma directly, but they were indirectly affected by it.[18]

For some, reactions to a traumatic events are temporary with immediate psychological and/or physical effects. For others, trauma can have lasting effects on a person’s life and well-being. Some people have a more sustained reaction to trauma. This reaction can become chronic or persistent with more severe, prolonged, or enduring mental health consequences (e.g., post-traumatic stress and other anxiety disorders, substance use and mood disorders) and physical impairments (e.g., arthritis, headaches, chronic pain) that can lead to a lack of trust or confidence in their body. It can also alter individual biology and behaviour over the life course, which can impact both interpersonal and intergenerational relationships, often resulting in a sense of loss of voice and powerlessness, and difficulty expressing thoughts and feelings.

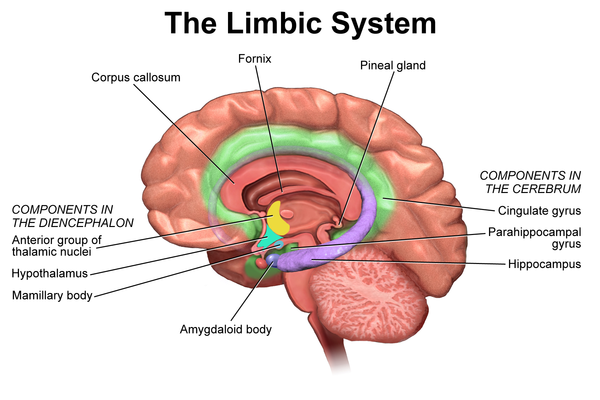

Role of the Limbic System[edit | edit source]

The limbic system is a collection of structures including the cerebrum, diencephalon, and midbrain. It supports many different functions, including emotion, behaviour, motivation, long-term memory, and olfaction.[19] Subparts of the limbic system ultimately regulate important aspects of our conscious and unconscious patterns (including our emotions, perceptions, relationships, behaviours and motor control). It is the part of the brain involved when it comes to behaviours we need for survival: feeding, reproduction and caring for our young, and fight or flight responses.

The limbic system is a system that helps us to process emotions such as fear, pleasure, and anger, and also helps to control our drives, whether a hunger drive, sexual drive, or a need for sleep. It also combines higher mental functions and primitive emotion into a single system often referred to as the emotional nervous system. It is not only responsible for our emotional lives but also our higher mental functions, such as learning and formation of memories.

The limbic system is dynamic, and can change in relation to input from a person’s environment. Experience changes this important brain region, and that may help explain why people’s psychological and physiological experiences change over time. Body awareness can play a role to help change the limbic system by training the brain to process information differently, assigning new emotions to old memories or supporting an individual in managing chronic stress, pain and trauma.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Gard G. Body awareness therapy for patients with fibromyalgia and chronic pain. Disability and rehabilitation. 2005 Jun 17;27(12):725-8.

- ↑ Ferro Moura Franco K, Lenoir D, dos Santos Franco YR, Jandre Reis FJ, Nunes Cabral CM, Meeus M. Prescription of exercises for the treatment of chronic pain along the continuum of nociplastic pain: A systematic review with meta‐analysis. European Journal of Pain. 2021 Jan;25(1):51-70.

- ↑ Gyllensten AL, Ekdahl C, Hansson L. Long-term effectiveness of basic body awareness therapy in psychiatric out-patient care. A randomised controlled study. Adv Physiother. 2009;11:2–12.

- ↑ Gyllensten AL, Ekdahl C, Hansson L 2009 Long-term effectiveness of Basic Body Awareness Therapy in psychiatric outpatient care. A randomized controlled study. Advances in Physiotherapy 11: 2–12

- ↑ Gyllensten AL, Jacobsen LN, Gard G. Clinician perspectives of Basic Body Awareness Therapy (BBAT) in mental health physical therapy: An international qualitative study. Journal of Bodywork and movement therapies. 2019 Oct 1;23(4):746-51.

- ↑ Solano Lopez AL, Moore S. Dimensions of body-awareness and depressed mood and anxiety. Western journal of nursing research. 2019 Jun;41(6):834-53.

- ↑ Mehling W, Wrubel J, Daubenmier J. Body awareness: a phenomenological inquiry into the common ground of mind-body therapies. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2011;6:6.

- ↑ Gyllensten AL, Hansson L, Ekdahl C 2003a Patient experiences of basic body awareness therapy and the relationship with the physiotherapist. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 7: 173–183

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gard G, Nyboe L, Gyllensten AL. Clinical reasoning and clinical use of basic body awareness therapy in physiotherapy–a qualitative study?. European Journal of Physiotherapy. 2020 Jan 2;22(1):29-35.

- ↑ Barrett L. F., Quigley K., Bliss-Moreau E., Aronson K. (2004). Interoceptive sensitivity and self-reports of emotional experience. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87 684–697. 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.684

- ↑ Solano Lopez AL, Moore S. Dimensions of body-awareness and depressed mood and anxiety. Western journal of nursing research. 2019 Jun;41(6):834-53.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fang ML, Sixsmith J, Lawthom R, Mountian I, Shahrin A. Experiencing ‘pathologized presence and normalized absence’; understanding health related experiences and access to health care among Iraqi and Somali asylum seekers, refugees and persons without legal status. BMC public health. 2015 Dec;15(1):923.

- ↑ Carta MG, Bernal M, Hardoy MC, Haro-Abad JM. Migration and mental health in Europe (the state of the mental health in Europe working group: appendix 1). Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health. 2005 Dec 1;1(1):13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1236945/

- ↑ Quickfall J. Cross-cultural promotion of health: a partnership process? Principles and factors involved in the culturally competent community based nursing care of asylum applicants in Scotland.https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/4466

- ↑ Health Challenges for Refugees and Immigrants by Ariel Burgess, VOLUME 25, NUMBER 2 https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ACB7A9B4B95ED39A8525723D006D6047-irsa-refugee-health-apr04.pdf

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Keys to Cultural Competency: A Literature Review for Evaluators of Recent Immigrant and Refugee Service Programs in Colorado, REFT Institute, Inc. March 2002. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/KeystoCulturalCompetency04.pdf

- ↑ Bialocerkowski A, Wells C, Grimmer-Somers K. Teaching physiotherapy skills in culturally-diverse classes. BMC medical education. 2011 Dec;11(1):34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3146421/

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No.(SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. Available from:https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf (last accessed 27 March 2022).

- ↑ Kiddle Limbic system facts for kids Available from: https://kids.kiddle.co/Limbic_system (accessed 28.12.2020)

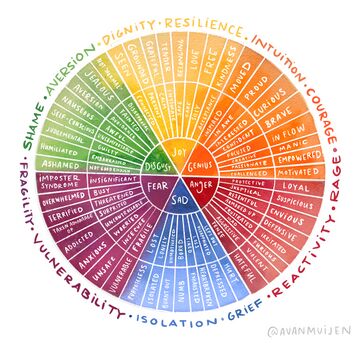

- ↑ Abby Vanmunijen. Emotions Wheel. Available from: https://www.avanmuijen.com/watercolor-emotion-wheel (accessed 2 March 2023).

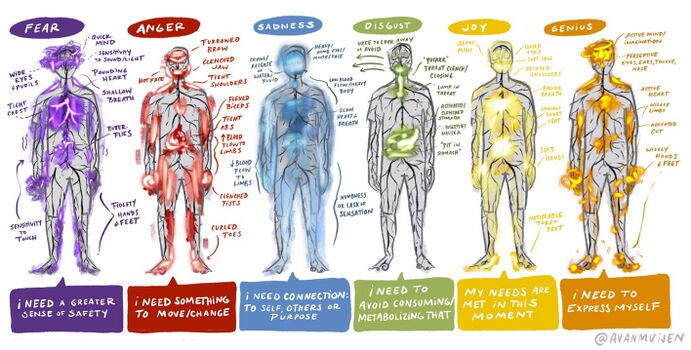

- ↑ Body Needs Mapping Worksheet. Available from: https://www.avanmuijen.com/watercolor-emotion-wheel (accessed 2 March 2023).