Biceps Tendinopathy

Original Editor - Cole Racich and Nick Tainter as part of the Temple University EBP Project

Top Contributors - Nick Tainter, Cole Racich, Abbey Wright, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, Fasuba Ayobami, David Herteleer, Wanda van Niekerk, Scott A Burns and Jacob Bischoff

Introduction[edit | edit source]

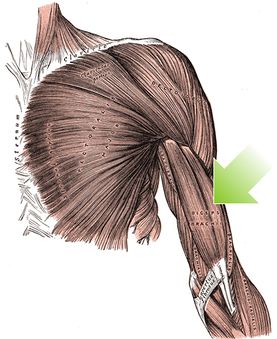

Proximal biceps tendinopathy is the inflammation of the tendon around the long head of the biceps muscle.. Biceps tendinitus can impair patients' ability to perform many routine activities.

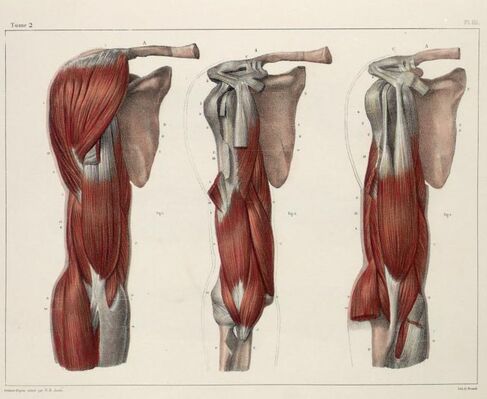

- Main function of the biceps muscle is forearm supination and elbow flexion.

- Biceps also contribute 10 percent of the total power in shoulder abduction when the arm is in external rotation[1].[2]

The 4 minute video below shows the classic presentation of long head of biceps (LHB) tendinopathy

Etiology[edit | edit source]

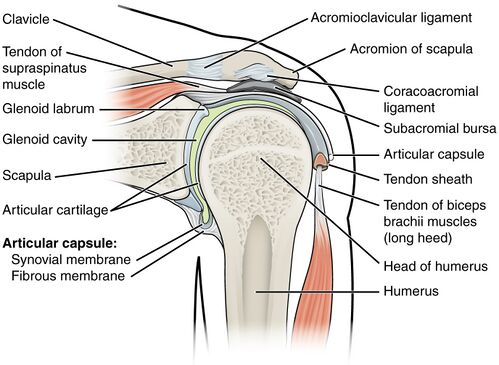

Biceps tendonitis describes a clinical condition of inflammatory tenosynovitis, most commonly affecting the tendinous portion of the LHB as it travels within the bicipital groove in the proximal humerus. The continuum of clinical pathology ranges from acute inflammatory tendinitis to degenerative tendinopathy.

- Primary bicipital tendinitis is much less common than cases where it is associated with concomitant primary shoulder pathologies (i.e., secondary cases). The etiologies for primary bicipital tendinitis are not well understood compared to the more common secondary presentations.

- Secondary cases are much more common and have been described in the literature with increasing frequency dating back to at least the early 1980s. In 1982, Neviaser et al. demonstrated the relationship between increasing LHB tendon inflammatory changes with increasing severity of rotator cuff (RC) tendinopathy.

Other associated shoulder pathologies include:

- Rotator cuff tendinitis and Chronic Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

- Subscapularis injuries

- LHB tendon instability/dislocation (seen in association with subscapularis injuries/tears)

- Direct or indirect trauma

- Inflammatory conditions

- Internal impingement of the shoulder (“Thrower’s” shoulder)

- External impingement/Subacromial impingement syndrome

- Glenohumeral arthritis[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Primary LHB tendinitis represents about 5% of cases of proximal biceps pathology. Although much less common, primary isolated cases are typically observed in young athletes participating in baseball, softball, volleyball, gymnastics, and/or swimming.

The vast majority of cases are seen in association with the aforementioned shoulder pathologies. Most commonly, LHB tendinopathy occurs in association with RC pathology, EI/SIS, or in tandem with subscapularis injuries. In the setting of RC tears, 90% of cases demonstrated concomitant LHB tendinopathy, and 45% of cases had additional LHB instability[1]

Pathological Process - Tendinopathic Cascade[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiology of LHB tendinitis/tendinopathy begins with

- The early stages of tenosynovitis and inflammation secondary to repetitive traction, friction, and shoulder rotation. Inflammation develops early on in the tendinous portion in the bicipital groove.

- The tendon increases in diameter secondary to swelling and/or associated hemorrhage, further compromising the tendon as it becomes mechanically irritated in its confined space. The resultant increased pressure and specific sites of traction predispose the tendon to pathologic shear forces.

- In addition, the sheath of the biceps tendon is a direct extension of the synovial lining of the glenohumeral joint. Thus, concomitant or preexisting RC pathology can directly compromise the LHB tendon itself. In the early stages of the disease, the LHB tendon remains mobile in the bicipital groove.

- As the pathophysiology escalates, there is an ensuing LHB sheath thickening, fibrosis, and vascular compromise. The LHB tendon undergoes degenerative changes, and associated scarring, fibrosis, and adhesions eventually compromise LHB tendon mobility. In effect, the tendon becomes pathologically “anchored” in the groove, further exacerbating the potential points of traction and overall increasing shear forces experienced by the LHB tendon along its course.

- In advanced, end-stage conditions, the LHB tendon can eventually rupture at its origin near the superior glenoid tubercle, or as it exits the bicipital groove near its musculotendinous junction.[1]

Clinical Presentation/ Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Characteristics of proximal biceps tendinitis include the following:

- Atraumatic, insidious onset of anterior shoulder pain

- Symptom exacerbation with overhead activities

- Pain radiating down the anterior arm from the shoulder

- Clicking or audible popping can be reported in the setting of proximal biceps instability

- Pain at rest, pain at night

- History or current sports, especially baseball, volleyball, and other overhead sports

- History or current manual/physical laborer occupations

In addition, a thorough history includes a detailed account of the patient’s occupational history and current status of employment, hand dominance, history of injury/trauma to the shoulder(s) and/or neck, and any relevant surgical history.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnosis of Anterior Shoulder Pain:[4]

- Acromioclavicular joint pathology

- Adhesive capsulitis

- Cervical spine pathology

- Glenohumeral osteoarthritis

- Glenohumeral instability

- Humeral head osteonecrosis

- Sub-acromial Impingement syndrome

- Rotator cuff tears

- Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions (SLAP)

- Pulley lesions[5]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Due to the lack of specificity in differentiating between biceps tendon pathology, subacromial impingement syndromes, and rotator cuff pathology, it is important to take an extensive history upon evaluation and not use these tests solely to make a diagnosis[6]

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Palpation: Pain with palpation over the bicipital groove (which is most felt in 10° of internal rotation) is a common physical finding for patients with biceps tendinopathy.[6][4][7][8]

- Range of Movement (ROM): Testing of cervical, shoulder and elbow AROM should all be completed as well as PROM of shoulder and elbow.

- Strength Testing: Strength testing of shoulder, elbow and wrist should all be completed to ensure no significant weakness of other structures. There may also be associated rotator cuff weakness due to the high prevalence of shoulder injuries accompanying biceps tendinopathy.

- Provocative tests: If any of these tests is positive, it indicates that impingement is present, which can lead to biceps tendinopathy. No validated cluster of diagnostic tests is currently available for ruling in or out biceps tendinopathy specifically[4]. Therefore, these tests should be used to help guide the diagnosis:

- Yergasons test: Yergason's test requires the patient to place the arm at his or her side with the elbow flexed at 90 degrees, and supinate against resistance. The test is considered positive if pain is referred to the bicipital groove.

- Neers test: involves internal rotation of the arm while in the forward flexed position. If the patient experiences pain, it is a positive sign of shoulder impingement syndrome or sub acromial pain syndrome.

- Hawkins test: the patient flexes the elbow to 90 degrees while the physician elevates the patient's shoulder to 90 degrees and places the forearm in a neutral position. With the arm supported, the humerus is rotated internally. The test is positive if bicipital groove pain is present.

- Speeds test: the patient tries to flex the shoulder against resistance with the elbow extended and the forearm supinated. A positive test is pain radiating to the bicipital groove..[2][14][1]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

- Radiographs including Bicipital groove view radiography. Routine radiographs are recommended, but in the majority of cases of LHB tendinitis without coexisting pathologies, these will be normal.[1]

- MRI

- Ultrasonography: is a good way to evaluate isolated tendinopathy extra-articulatory, which is also the most cost effective.[2] [6]

The diagnostic criteria for biceps tendinopathy were defined as meeting at least one of the following:

- Tendon sheath swelling (transverse view: for women ≥4.6, for men ≥5.5!mm;longitudinal view: for women ≥2.5, for men ≥2.8!mm, as adopted from Schmidt et al.)

- Tendon sheath fluid accumulation (abnormal hypoechoic or anechoic accumulation relative to the subdermal fat, although occasionally this could be isoechoic or hyperechoic) in intraarticular material that is displaceable and compressible and ≥3!mm, as adopted from Bruyn etal. In addition to the diagnostic criteria, increased color flow signals were recognized around the swollen biceps tendon as essential to a biceps tendinopathy diagnosis.

All involved with the musculoskeletal US examination reached a consensus on these diagnostic criteria for the purpose of avoiding operator-dependent misdiagnosis.[2]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Main outcome measures of biceps tendinopathy are:

- DASH (disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) scoring,

- Range of motion,

- VAS/NPRS

- Simple Shoulder Test[9]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative: Initial treatment should consist of pain management and use of NSAIDs. If this is unsuccessful the use of steroid injections may be helpful in managing pain. [10][11] Or for more persistent presentations, corticosteroid injections along the tendon sheath may be indicated.[7] In low-functioning or medically complicated patients, conservative measures should always be pursued initially.[10]

Surgical: If conservative management has not been successful then surgical management can be considered. This is indicated in higher functional level patients or athletes with extensive active pathology accompanied with other shoulder pathology such as rotator cuff tears.

- Normally a biceps or tenodesis is performed either via arthroscopic or open incisions. [10][11][12]

- Surgical management of biceps tendinitis includes removing the long head of the biceps tendon via arthroscopic tenodesis. Research has shown this to provide sufficient reductions in pain levels while maintaining normal biceps function.[4]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Successful physical therapy regimens target the underlying source(s) contributing to the LHB tendon pathology. Potential factors predisposing to biceps-related shoulder injuries include glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) in overhead-throwing athletes/baseball pitchers, poor trunk control, scapular dyskinesia, and internal impingement.

Physical therapy initially focusing on unloading followed by reloading the effected tendon (see Tendinopathy rehab page for full details).

- This may start with isometric training if pain is the primary issue progressing into eccentric training and eventually concentric loading as with other forms of tendon rehab.

- Stretching and strengthening programs are a common component of most therapy programs. Therapists also use other modalities, including ultrasound, iontophoresis, deep transverse friction massage, low-level laser therapy, and hyperthermia; however evidence for these modalities are has low quality.[13]

- The physical therapist must consider both the patient's subjective response to injury and the physiological mechanisms of tissue healing; both are essential in relation to a patients return to optimal performance.

As a preface to discussion of the goals of treatment during injury rehabilitation, two points must be made:

- Healing tissue must not be overstressed and a very slow heavy loading program should be undertaken. During tissue healing, controlled therapeutic stress is necessary to optimize collagen matrix formation, but too much stress can damage new structures and slow the patient’s rehabilitation

- The patient must meet specific objectives to progress from one phase of healing to the next. These objectives may depend on ROM, strength, or activity. It is the responsibility of the physical therapist to establish these guidelines.[14]

Exercise therapy should include:

- Restoring a pain free range of motion - Pain free range can be achieved with such activities as PROM, Active-Assisted Range of Motion (AAROM), and mobilization via shoulder manual therapy

- Proper scapulothoracic rhythm.[11] .

- Painful activities such as abduction and overhead activities should be avoided in the early stages of recovery as it can exacerbate symptoms[11].

- Strengthening program consisting of heavy slow loading should begin with emphasis on the scapular stabilizers, rotator cuff and biceps tendon[14].

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Biceps tendinopathy is an inflammation that can be caused by the normal ageing process as well by a degenerative process which usually occurs in athletes with repetitive overhead movements. It is important to understand, that this inflammation has many different causes and is frequently accompanied by other shoulder pathologies such as: SLAP-lesions, rotator-cuff tears or instability.

- The patient will primarily experience pain localised in the bicipital groove and may radiate toward the insertion of the deltoid muscle, or down to the hand in radial distribution. Leading to an increase in pain on pull, push and overhead motions.

- The best way to diagnose biceps tendinopathy, is by comparative palpation of the biceps tendon along the intertubercular groove, or otherwise by doing a ultrasonography (extra-articulair).

- Treatment consists of conservative or surgical treatment. Surgery should be considered if conservative measures fail after three months. Structures causing primary and secondary impingement may be removed, and the biceps tendon may be repaired if necessary.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Varacallo M, Mair SD. Proximal biceps tendinitis and tendinopathy. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK533002/ (accessed 29.9.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Huang SW, Wang WT. Quantitative diagnostic method for biceps long head tendinitis by using ultrasound. The Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013.

- ↑ Clinical Physio. Classic Long Head of Biceps Tendinopathy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4vYM7JXSW8 [Last accessed 25/10/2015]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Churgay CA. Diagnosis and treatment of biceps tendinitis and tendinosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Sep 1;80(5):470-6.

- ↑ Park SS, Loebenberg ML, Rokito AS, Zuckerman JD. The shoulder in baseball pitching: biomechanics and related injuries--Part 1. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 2002 Dec 22;61(1-2):68-.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Ahrens PM, Boileau P. The long head of biceps and associated tendinopathy. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2007 Aug;89(8):1001-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nakata W, Katou S, Fujita A, Nakata M, Lefor AT, Sugimoto H. Biceps pulley: normal anatomy and associated lesions at MR arthrography. Radiographics. 2011 May 4;31(3):791-810.

- ↑ Salim M. Hayek,Binit J. Shah,Mehul J. Desai,Thomas C. Chelimsky. (2015) Pain Medicine An Interdisciplinary Case-Based Approach. OUP USA

- ↑ Biz C, Vinanti GB, Rossato A, Arnaldi E, Aldegheri R. Prospective study of three surgical procedures for long head biceps tendinopathy associated with rotator cuff tears. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2012 Apr;2(2):133.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Longo UG, Loppini M, Marineo G, Khan WS, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Tendinopathy of the tendon of the long head of the biceps. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2011 Dec 1;19(4):321-32.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, Provencher MT, Mazzocca AD, Verma NN, Romeo AA. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010 Nov 1;18(11):645-56.

- ↑ Snyder GM, Mair SD, Lattermann C. Tendinopathy of the long head of the biceps. InRotator Cuff Tear 2012 (Vol. 57, pp. 76-89). Karger Publishers.

- ↑ Andres BM, Murrell GA. Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008 Jul 1;466(7):1539-54.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Thomas R. Baechle.(2008) Essentials Of Strength Training And Conditioning. (third edition). National Strength and Conditioning Association. Human kinetic