Baxter's Nerve Entrapment

Top Contributors - Habibu Salisu Badamasi and David Olukayode

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The most common complaint in the foot and ankle region is heel pain. The most of these problems, however, are related to plantar fasciitis. [1] Up to 20% of cases of chronic heel pain are caused by Baxter's nerve entrapment. However, it's an often-overlooked source of heel pain.[2]

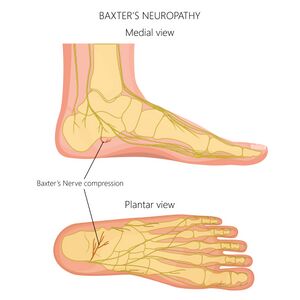

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

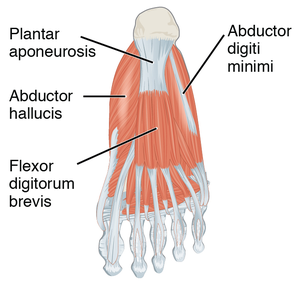

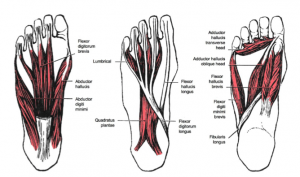

Baxter’s nerve also known as inferior calcaneal, is the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve arising within the tarsal tunnel. lateral plantar nerve has sensory components to the calcaneal periosteum, the long plantar ligament and the lateral plantar skin, and motor fibers to the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digitorum brevis and quadratus plantae. The first branch of the lateral plantar nerve originates from the lateral plantar nerve near the bifurcation of the tibial nerve or it may arise from the tibial nerve prior to its bifurication. It then dives through the superficial fascia at the superior border of the abductor. At this level, the investing fascia of the abductor is thicker laterally because of the reinforcement from the interfasicular ligament in continuity with the medial intermuscular septum. It travels distally between the lateral abductor fascia and the medial edge of the quadratus. When it reaches the lower border of the abductor hallucis, it turns and courses laterally, passing 5.5 mm anterior to the medial calcaneal tuberosity (or spur) and between the quadratus and the underlying flexor brevis until it reaches its distal target of the abductor digiti minimi.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Baxter's nerve is vulnerable to entrapment because of its course, and the most common location is the tight fascia of the abductor hallucis and the medial aspect of the quadrates plantae muscle. However, two point have been proposed as possible entrapment reasons.

- The first is the point where the nerve turns laterally between the medial edge of the quadratus plantae and the thick lateral fascia of the abductor hallucis.

- The second is the point where the nerve courses anterior to the tuberosity and/or spur. An increase in cubic contact of this passage (via a spur or muscle hypertrophy) and/or pronation of the rearfoot/midfoot complex, causing impingement at the nerve’s sharp turn are both possible predisposing conditions.[2]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Subjective assessment[edit | edit source]

- Pain behavior: Ask questions to investigate if the pain worse after rest or after activity or does the pain radiate distally or laterally?

- Pain duration: Ask questions about how long have the symptoms been present?

Objective assessment[edit | edit source]

- physical exam the heel by palpating the proximal and distal plantar fascia. palpate and percuss the tibial and medial calcaneal nerve. palpate the abductor hallucis origin.

- Assess for pain with compression of the heel from side to side; and see if performing the windlass test induces symptoms

- clinically, to differentiate baxter's nerve entrapment from other heel pain. Tenderness above the abductor hallucis origin, which can induce laterally radiating discomfort and/or parathesias. Using Phalen's maneuver can also provoke symptoms in several cases. Invert and plantarflex the foot to achieve this motion. The porta pedis narrows and compresses the nerve at the upper edge of the abductor hallucis as a result of this. You'll also want to see how well the patient can abduct the fifth digit. Because some patients are born without this capacity, make sure to compare the afflicted and contralateral sides. The patient may not be able to abduct the fifth digit if Baxter's nerve entrapment is present. We have not found this to be a reliable indicator in clinical practice.[2]

- Patients with classic Baxter's nerve entrapment, on the other hand, frequently deny first-step pain while claiming that their symptoms increase with continuous activity. They could also have pain that radiates laterally.[2]

Examinations[edit | edit source]

Biomechanical exam[edit | edit source]

Typically, therapists will notice a pronated foot structure during the biomechanical assessment.[2]

Radiography and Bone scan[edit | edit source]

Osseous pathology can be ruled out with simple radiographs and bone scans.[2]

Serologic testing[edit | edit source]

Serologic testing may be used if you suspect systemic arthropathy.[2]

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Plantar fasciitis

- Seronegative arthritis-induced inflammation

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome

- Medial calcaneal neuritis

- Heel spurs

- Trauma

- Fat pad atrophy

- Calcaneal stress fractures

- Periosteal inflammation

Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatments[edit | edit source]

Simple treatment is done by taping or orthotics, stretching, and foot strengthening.

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Surgical release of the nerve has been found to be effective in the management of Baxter's nerve entrapment.[1]

Ultrasound-Guided Hydrodissection injection[edit | edit source]

An ultrasound-guided anesthetic injection may also be used for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The injection of a fluid medium, such as local anesthetic or saline, with or without corticosteroids, or even 5% dextrose in water, to dissect across structures or fascial planes under continuous ultrasound observation is known as ultrasound-guided hydrodissection .[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Sahoo RK, Peng PW, Sharma SK. Ultrasound-Guided Hydrodissection for Baxter’s Neuropathy Secondary to Plantar Fasciitis: A Case Report. A&A Practice. 2020 Nov 1;14(13):e01339.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Stephen Offutt DP, Patrick DeHeer DP. How to address Baxters nerve entrapment. Podiatry Today. 2004 Nov 3;17(11).