Back Education Program

Original Editors - Hannah Anderson, Dan McCoy, Rebecca Porter and Millie Ware

Top Contributors - Rebecca Porter, Hannah Anderson, Elaine Lonnemann, Laura Ritchie, Millie Deason, Kim Jackson, Daniel McCoy, Admin, Evan Thomas, Shreya Pavaskar, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton and Kalyani Yajnanarayan

About Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

Are you experiencing low back pain? You are not alone! Look at these statistics...[1][edit | edit source]

- As many as 80% of Americans have symptoms of low back pain during their lifetime[2]

- Low back pain is the leading cause of injury and disability for those younger than 45 years old[2]

- Each year, approximately $26 billion dollars are spent in the United States for the treatment of low back pain.

Is pain always bad? No. Pain is the body's way to receive messages that there is a threat or something is wrong.

Your brain processes this pain message and responds in a way that will reduce the threat. Initially, when tissues were injured, the nerves in your back (which have sensors) sent messages of pain to the brain. The brain, very much like a processor in a computer, takes this message or code and decides where it should be stored and which systems should deal with it. Those systems in the brain then send messages back through nerve pathways to the muscles to tell them to move the back gently and carefully so those tissues can heal. It is an amazing system in the brain, influenced by chemicals and the manner in which the pain messages are routed or circuited. Over time tissues heal and the healing process begins immediately. Usually within two weeks any swelling that caused the sensors to light up and send pain messages to your brain has gone away. Most tissues heal completely within four to six weeks.

The brain can be sensitized or desensitized by several things including our beliefs about pain and our understanding of how the body heals. You may have heard stories about how soldiers in war times have stated they felt no pain even with limb amputation. All they remembered feeling was joy, knowing they weren't dead and would get to go home. This is an example of how the brain can interpret pain and desensitize the response It can be sensitized or over-reactive by our emotions, events that occur in our lives that may increase feelings of anxiousness or fear. The amount of pain you are feeling doesn't equal the amount of tissue damage you may have. In fact your tissues may have healed completely but you are still experiencing pain.

The good news is that these processes are normal and there are things that can help you calm the nerves down that are sensitized or on call.

Understanding anatomy will help you to understand how to care for your back.[3][edit | edit source]

Your spine is wonderfully designed to allow you to move. It is also designed to help you absorb and distribute forces from the many activities you do.

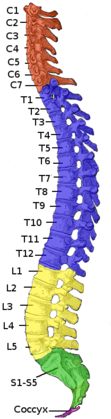

Your spine is made up of 33 small bones called vertebrae. Together, they form what is know as the vertebral column. There are 7 vertebrae in the cervical region which is your neck; 12 vertebrae in the thoracic region which is your upper back; 5 vertebrae in your lumbar spine which is your lower back; and 5 sacral vertebrae and 4 coccyx which are located below that.

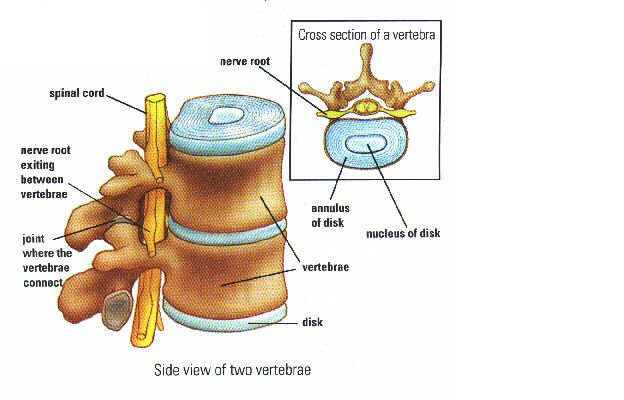

Between each of the vertebrae is a disc that binds the vertebra together like a very strong ligament. It acts as a cushion and a shock absorber. These intervertebral discs are made up of two parts-- the nucleus pulposus and the annulus fibrosis. The nucleus pulposus is in the middle of the disc and is jelly-like due to its large water content; it is composed of up to 80% water! The annulus fibrosis surrounds this nucleus and so forms the outer part of the disc. These discs play an important role in keeping the back healthy!

Other important parts of the spine:

- Facet joint: the joint where the vertebrae connect

- Spinal cord

- Nerves: diverge off of the spinal cord and run to different parts of the body

Your spine has three natural curves that begin to develop from the moment a baby lifts his/her head and gravity begins to work on the body. The curves keep the spine from being completely rigid and help the spine to tolerate a little bit more compression. To understand the normal curves of a spine, there are 2 terms you need to know—lordosis and kyphosis. Lordosis is when the spine curves inward and a kyphosis is when the spine curves outward. The cervical portion of the spine is in a lordosis, the thoracic portion is in a kyphosis, and the lumbar spine is in a lordosis. These nice curves of the back increase the load bearing capacity of the spine.

The spine has 4 main motions—forward bending, backward bending, sidebending, and rotation. These motions can also be coupled. For instance, you can have forward bending with rotation or backward bending with sidebending. Below, we demonstrate these motions and report typical lumbar spine active range of motion.

| Forward Bending 60 degrees | Backward Bending 25 degrees | Lateral Flexion 25 degrees | Rotation 30 degrees |

|

|

|

|

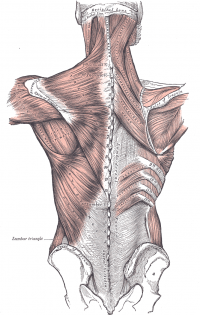

Muscles[edit | edit source]

Many muscles work together to help make these spinal motions possible! These back muscles can be classified into three different layers-- superficial, intermediate, and deep.[4] The muscles produce spinal movements and also help to keep the spine stable. In order to keep these muscles healthy, we must stay active.

| File:Interactive Spine - Thoracic Vertebral Spine - L7F22.jpg |

|

File:Interactive Spine - Lumbar Vertebral Spine - L7F19.jpg |

About Neck Pain[5][edit | edit source]

How common is neck pain?[edit | edit source]

Here are a few statistics on the prevalence of neck pain:

- Neck pain reported to be 2nd most common musculoskeletal disorder that leads to disability and injury claims[2]

- 2002: 13.8% of population > 18 years old in U.S. reported neck pain[2]

- Up to 50% of people with neck pain have ongoing symptoms for > 3 months, therefore are categorised as "Chronic" patients[6]

Anatomy of the neck[edit | edit source]

Just as with low back pain, it is important to understand the anatomy behind your neck pain! The neck is anatomically separated into the upper cervical spine and the lower cervical spine. There are 7 vertebrae that make up the cervical spine.

The first cervical vertebra (C1) is called the Atlas. It has no vertebral body or spinous process. This vertebra articulates with the Occiput, which is the base of the skull. This articulation is labeled as the OA joint; its primary motion is flexion and extension at the joint. It also performing side-bending with opposite rotation.

The second cervical vertebra (C2) is called the Axis; it has a large spinous process. The articulation between the Atlas and Axis is called the AA joint and its primary motion is rotation.

The following pictures demonstrate the motions of the lower cervical spine (C3-C7) and report the typical active range of motion.[2]

| Flexion: 54 degrees |

Extension: 77 degrees |

Sidebending: 45 degrees |

Rotation: 70-80 degrees |

|

Muscles[edit | edit source]

The muscle mentioned in the section About Back Pain also can play a role in neck pain, especially those muscles of the superficial layer. Also, deep inside the back of the neck are four important muscles called the suboccipital muscles.[4]

There are certain factors that can put you at risk for neck pain. See if any of these describe you:

- Working at a desk that is ill fitting to your body

- Working at a computer for long periods of time

- Sitting with bad posture for long periods of time

- Working on above head activities (i.e. painting) for long periods of time

For Physical Therapists: What information should you be collecting when treating a patient with neck pain? Have a look at the Cervical Tool Kit to help you identify or classify your patient and choose evidence informed interventions. CERVICAL TOOL KIT

Why Does My Back hurt?[edit | edit source]

Back pain is becoming increasingly prevalent in our population. Pain is an indication that your body is working to protect that part of the body. Pain can be a good guide to the best healing behaviors; understanding pain can help you to deal with it effectively.[7] Back pain can be caused by a multitude of structures, but the exact structure causing the pain cannot be identified. This is most likely because of the complex interactions of the brain and spinal nerves often times referred to as the Pain Matrix.

Any structure in your back that has a nerve supply can send messages to the brain if it is injured. Back pain can come from the disc, facet joint, spinal nerve root, ligaments, muscles, bones, fascia or neurogenic claudication.

Intervertebral Disc:

The natural lordotic posture decreases the pressure on the disc compared to the straight posture which can put pressure on the disc and can push fluid from the nucleus pulposus into the vertebral body (schmorl’s nodes). It is important to differentiate herniated disc (space occupying) which refers into the leg vs other conditions (inflammation reaction, spasms, strains, facet syndrome) which are more localized in pain.

Functional anatomy of the intervertebral disc:[8]

- In forward bending or flexion, the disc bulges anteriorly/forwards and the nucleus pulposus goes posteriorly

- In backward bending or extension, the disc bulges posteriorly/backwards and the nucleus pulposus goes anteriorly

- In sidebending or lateral flexion, the disco bulges towards the side in which in movement is occurring (eg. right sidebending, right disc bulge)

- If the disc looses height, can put pressure on the facet joints, possibly increasing the risk of arthritis, and put pressure the nerve roots by decreasing the foraminal height

Injury to the disc:

- Protrusion: disc bulge posteriorly without rupture of annulus fibrosis

- Prolapse: outermost fibers of the annulus fibrosis contain the nucleus

- Extrusion: annulus fibrosis is perforated and discal material into the epidural space

- Sequestrated: fragments of annulus and nucleus are outside the disc proper (can lead to pressure on neurological tissues and cause an inflammatory response)

Anterior disc herniation:[8]

- Occurs when someone is in extension, or leaning backward, which puts pressure on the anterior/front of the disc causing it to herniated/prolapse/bulge.

- This can put pressure on nerves in the lower abdomen causing weakness or numbness, anterior longitudinal ligament, vertebral body, and transverse abdominus which can all cause pain.

Posterior disc herniation:[8]

- Occurs when some is in flexion, leaning forward, which puts pressure on the posterior/back of the disc causing it to herniate/prolapse/bulge.

- This can put pressure on your spinal cord or nerve root causing pain/weakness/numbness/reduced reflexes and the posterior longitudinal ligament causing pain

For Physical Therapists: What information should you be collecting when treating a patient with low back pain? The TREATMENT BASED CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM has been associated with excellent outcomes[2]

What can I do about my Low Back Pain?[edit | edit source]

Treatment for Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

Treatment may include;

- Proper posture

- Aerobic conditioning

- Traction

- Manual therapy (mobilizations, stretching)

- Self-stretching

- Exercise

For Physical Therapists[edit | edit source]

Stanton et al created a treatment based classification based system for low back pain.[9]

Which exercises does research show to be effective for lumbopelvic stabilization? [10][edit | edit source]

Exercise is a significant factor in the rehabilitation process. Studies have found that exercise is more effective at improving function and decreasing pain than seeing a family physician. [11] Goal of exercises: to restore strength and endurance of the Transverse Abdominus and Lumbar Multifidus.

Abdominal bracing[edit | edit source]

- Abdominal bracing with heel slides

- Abdominal bracing with leg lifts

- Abdominal bracing with bridges

- Abdominal bracing with standing row exercise

- Abdominal bracing with walking/standing

Erector Spinae/Multifidus[edit | edit source]

- Quadruped arm lifts and bracing

- Quadruped leg lifts and bracing

- Quadruped alternate arms and legs with bracing

Extension Based Exercises[edit | edit source]

Cow Stretch

Prone Press Ups

Flexion Based Exercises[edit | edit source]

Cat Stretch

Prayer Stretch

Single Knee to Chest

Specific Exercise Category [12][edit | edit source]

Subjective:

- Symptoms distal to buttocks

Objective:

- Pain centralizes with a specific movement (can be flexion or extension)

Proper Lifting Techniques[edit | edit source]

Squat lift

- Plan Your Lift: Know how heavy the object is. Clear a path and know where you are going with the object.

- Lift Close to your body: This will make you stronger and more stable. Make sure you have a firm hold on the object and balance it close to the body.

- Feet shoulder width apart: This allows for a solid base of support.

- Bend your knees while keeping your back straight: Avoid any twisting motions.

- Tighten your stomach muscles: This will hold your back in good alignment and prevent excessive force on the spine. Avoid holding your breath.

- Lift with your legs: Your leg muscles are stronger than your back so use them.

- If you are straining, get help: Get help if the object is too heavy or you are in an awkward position.

Squat - Remember to:

- Keep back straight

- Knees behind toes

- Keep knees parallel

Golfer’s Lift

- The Golfer’s lift is another lifting technique that you can use to pick something off the floor

- This works best when you hold onto something like a chair or table as you bend over

- When you bend over kick the leg your are not standing on out straight behind you - This will help keep your back straight

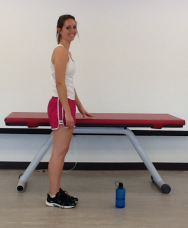

Diagonal Standing

- Stand with one foot slightly in front of the other and distribute your weight evenly between both legs

- This is a preferred position over straight standing

- Avoid putting all of your weight onto one leg while standing.

Aerobic Activity [13][edit | edit source]

Types: Walking, jogging, running, cycling, swimming, climbers, steppers, elliptical machines, ski machines, aerobic dance

Warm up/cool down – low to moderate activity

- 5-10 minutes of warm up (adjust to demands placed on the body)

- 5-10 minutes of cool down (recovery of heart rate and BP)

- 10 minutes of stretching AFTER the warm up OR cool down

ACSM Guidelines:=

- Frequency: 5 days/week

- Duration: 150 minutes per week (minimum)

- Intensity: 40-60% HRmax (HRmax = 220-age)

Benefits of exercise are improved joint health due to low impact exercises, increase bone density due to weight bearing exercises, improving energy, reducing health risks, improving circulation, and reducing stress and improving your mood. Aerobic activity is equally effective at reconditioning muscles as exercise and can also help in decreasing pain, improving your mood, and improving your functional capabilities.[14] Lack of exercise increases your risk of obesity and other co-morbidities increases; this can lead to increased pressure on the spine and decreased flexibility.

What can I do about my Neck Pain?[edit | edit source]

There are specific treatments based on each classification of neck pain: [2]

Cervical Hypomobility[edit | edit source]

- AROM exercises

- Cervical and thoracic mobilization/manipulation isometric or thrust manipulation techniques

- Nonthrust manipulation

Cervical Radiculopathy[edit | edit source]

- Cervical traction (manual/mechanical)

- ULNT 1 AROM

- Thoracic spine manipulation

- Postural exercises

Cervical Instability[edit | edit source]

- Postural education

- Cervical stabilization exercise program

- Mobilization/manipulation above and below hypermobilities

- Ergonomic corrections

Acute Pain (Whiplash)[edit | edit source]

- Gentle AROM within patient tolerance

- Activity modification to control pain

- Relative rest

- Physical modalities

- Intermittent use of cervical collar

- Gentle manual therapy and exercises, but avoidance of pain-inducing manual therapy techniques or exercises

Cervicogenic Headache[edit | edit source]

- Cervical and thoracic mobilization/manipulation

- Strengthening neck and postural muscles

- Postural education

What does the literature say about neck pain?[edit | edit source]

Exercise!

Evidence from the literature says that exercise has a significant effect in reducing chronic non-specific neck pain for short term (<1 month) and intermediate term (1-6 months) [15]

Neck Exercises[edit | edit source]

- OA flexion (chin tuck): A slight nod while keeping your head in neutral

- Flexion with chin tuck: While lying on your back tuck in your chin, lift off until your head clears the table and hold for 3-5 seconds maintaining the chin tuck

- Extension with chin tuck: While laying on your stomach tuck your chin, lift your head off table while maintaining chin tuck and hold 3-5 seconds

- 4-way Isometrics: Lightly press into your hand in flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation

Exercises for Scapular Stabilizers (muscles attached to your shoulder blade)

- Middle Trapezius: With band or lying on stomach, Thumb pointing in the direction exercise is moving, Pinch shoulder blades

- Lower Trapezius: Lying down making a half Y bring your shoulder blade back and down

- Seated Row: Upright Sitting Posture, Pull at elbows, Pinch shoulder blades together

- External Rotation: Elbows at sides, Thumbs pointing out, Shoulders back, Rotate outward

- Scapular Clock: Turn shoulder blade into a clock, Move shoulder blade to each number, retraction and depression are critical, Numbers 9, 8, 7, 6 are important

Stretches[edit | edit source]

Don't forget the thoracic spine![edit | edit source]

A clinical prediction rule was developed to help classify patients with mechanical neck pain that will experience early success from thoracic spine manipulation. Six variables were found: [16]

1. Symptoms < 30 days

2. No symptoms distal to the shoulder

3. Looking up does not aggravate symptoms

4. FABQPA score < 12

5. Diminished upper thoracic spine kyphosis

6. Cervical extension < 30 degrees

If a patient demonstrates 3 of the 6 variables the chance of experiencing a successful outcome improves from 54% to 86%. If a patient has 4 of the 6 variables the chance of a successful outcome rises to 95%.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Chou, MD Lumbar imaging guidelines

APTA Low Back Pain Infographic

Find a PT on the American Physical Therapy Association website

Orthopaedic Section - APTA: Clinical Guidelines for Neck Pain

Orthopaedic Section - APTA: Clinical Guidelines for Low Back Pain

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Cynergy Physical Therapy. Back Pain. http://www.cynergypt.com (assessed September 23 2013).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Olson, KA. Manual Physical Therapy of the Spine. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009.

- ↑ Physicians Plus.Vertebrae. http://www.physiciansplus.net (accessed September 16 2013).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Tank P. Grant's Dissector. 15th ed. Little Rock, AR: Wolters Kluwer; 2013.

- ↑ Ahern Family Chiropractic. Seizures. http://ahernfamilychiro.com (accessed September 24 2013).

- ↑ Mansfield M, Thacker M, Spahr N, Smith T. Factors associated with physical activity participation in adults with chronic cervical spine pain: a systematic review. PHYSIOTHERAPY [Internet]. [cited 2019 Feb 20];104(1):54–60. Available from: http://ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edswsc&AN=000426458600008&site=eds-live

- ↑ Butler D, Moseley. Explain Pain. Adelaide City Way, SA: Noigroup Publications; 2003.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Neumann, DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation 2nd Edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc; 2010.

- ↑ Stanton T et al. Evaluation of a Treatment-Based Classification Algorithm for Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Physical Therapy. 2011; 91:496-509.

- ↑ Hicks GE., Fritz JM., Delitto A., McGill SM. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program, Arch Phys Med Rehabilitation 2005; 86; 1753-1762

- ↑ Hettinga et al. A systematic review and synthesis of higher quality evidence of the effectiveness of exercise interventions for non-specific low back pain of at least 6 weeks' duration. Physical Therapy Reviews [serial online]. September 2007;12(3):221-232. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Browder D, Childs J, Cleland J, Fritz J. Effectiveness of an Extension-Oriented Treatment Approach in a Subgroup of Subjects with Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Physical Therapy. 2007; 87: 1608-1617.

- ↑ Thompson WR, Gordon NF, Pescatello LS, eds. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th ed. Baltimore: American College of Sports Medicine; 2010.

- ↑ Hettinga D, Jackson A, Moffett J, May S, Mercer C, Woby S. A systematic review and synthesis of higher quality evidence of the effectiveness of exercise interventions for non-specific low back pain of at least 6 weeks' duration. Physical Therapy Reviews [serial online]. September 2007;12(3):221-232. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Bertozzi et. al. Effect of Therapeutic Exercise on Pain and Disability in the Management of Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Phys Ther. 2013; 93:1026-1036

- ↑ Cleland et al. Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule for Guiding Treatment of a Subgroup of Patients with Neck Pain: Use of Thoracic Spine Manipulation, Exercise, and Patient Education. Phys Ther. 2007; 87: 9-23.