Baastrup Syndrome

Original Editors - Fien Selderslaghs, Mirabella Smolders, Matthias Steenwerckx, Wout Theys

Top Contributors - Sofie Bourdinon, Scott Cornish, Nikki Rommers, Admin, Arno Vrambout, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Fien Selderslaghs, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Vidya Acharya, Ceulemans Lisa, Aarti Sareen, 127.0.0.1 and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Baastrup’s Disease, generally known as Kissing Spine, is characterised by degenerative changes of both the spinous processes and interspinous soft tissues of two neighbouring vertebrae. This syndrome was first diagnosed by Baastrup in 1933.[1] [2] It is described as a condition where adjoining lumbar spinous processes become closely approximated to one another, resulting in the formation of a new joint between them.[3], [1], [4],[2] Kissing Spine mainly affects the lumbar area of the spine, with L4-L5 being the most frequently affected level [5], but it has also been reported in the cervical spine.[6]

Kissing Spine has numerous consequences such as the formation of hypertrophic spinous processes, which can lead to mechanical back pain in combination with degenerative disc disease.[3] [2] In some cases, the syndrome can also evoke neuromuscular damage.[7]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The lumbar spine, consisting of 5 separated vertebrae, is located between the thoracic spine and the sacrum. Those five vertebrae are the largest of the spine and increase in size from superior to inferior.[8]

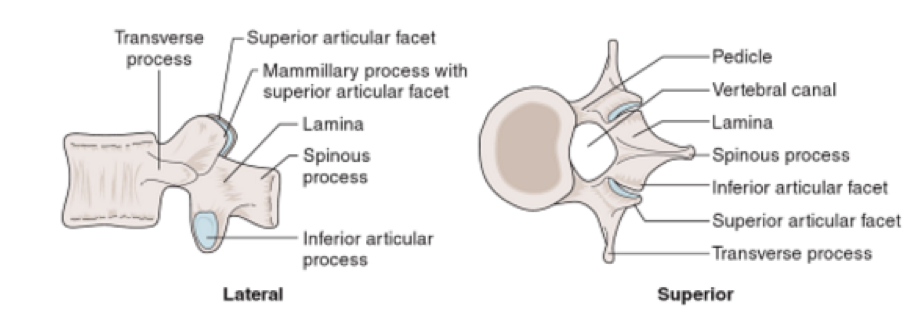

The lumbar vertebrae consist of various parts, in particular the vertebral body, the posterior elements (one process spinous and two processes transversus) and two pedicles.[9] Due to the weight-bearing function of the lumbar spine, the lumbar vertebral bodies are larger than the other vertebral bodies of the spine.[9] The processes spinous are thick and broad, and are dorsally and caudally orientated.[10] The pedicles are the junction between the vertebral body and the neural arch.[11]

Figure 1: Aspects of the Lumbar vertebrae [11]

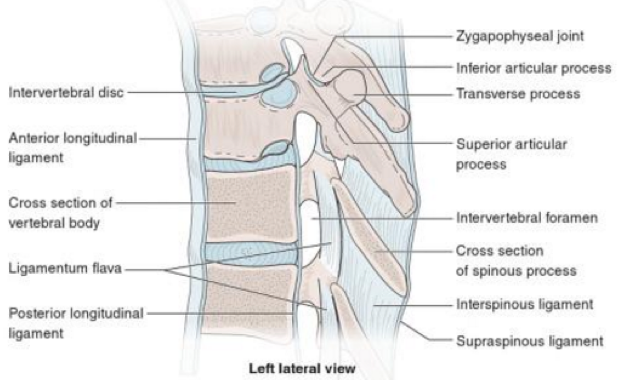

Stability of the lumbar spine is necessary during functional activities. This is primarily obtained by the muscles, which are attached to the posterior elements of the vertebrae, therefore, the spinous processes are subjected to major forces during movements.[10] Along with the muscular structures, ligaments also provide a stabilising function and as a result they also undergo large compressive loads during movement.[12]

Due to the high loads on the lumbar spine, there is a higher incidence of pain compared to other regions.[8] The baastrup syndrome can occasionally result in the formation of a bursa in the intermediary interspinous soft tissues [5],[13]

Figure 2: Vertebral Ligaments [11]

The interspinous ligament connects two adjacent spinous processes' and its primarily function is preventing excessive spinal flexion by limiting separation of the spinous processes'. It also controls vertebral rotation during flexion, helping the facet joints remain in contact while gliding. The supraspinous ligament is attached to the posterior tips of the spinous processes from approximately C7 to L4-L5. It limits spinal flexion and resists separation of two neighbouring spinous processes'. The posterior part of the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments is sensory innervated. The role of this input is to give proprioceptive information and protect against excessive forces. [10]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

A few studies have investigated the influence of the age on Baastrup Syndrome. DePalma et al. demonstrated that the average age of patients with Baastrup’s disease is 75.[14] which was supported by Maes R. et al. that Baastrup Syndrome is more common amongst elderly persons, but this nit preclude incidence in younger individuals. The effect of gender is still unknown, so further research is necessary.[15]

Age is not the only factor that is responsible for the evolution of Baastrup Syndrome. Other risk factors are:[2] [5]

- Excessive lordosis which results in increased mechanical pressure

- Repetitive strains of the interspinous ligament with subsequent degeneration and collapse

- Incorrect posture

- Traumatic injuries

- Tuberculous spondylitis

- Bilateral forms of congenital hip dislocation

- Stiffening of the thoracic spine or the thoracolumbar transition

- Obesity

The cause of pain is described as being mainly mechanical due to the neighbouring spinous processes coming into contact. Pain worsens with hyperextension or increased lordosis which can been seen in patients with obesity, limitation of hip movements and pro elite swimmers.[6][15]

Baastrup syndrome can occur independently or together with symptoms of other disorders, such as spondylolisthesis and spondylosis with osteophyte formation, and a loss of disc height.[5]

The precise prevalence in the population remains still uncertain, but Kacki et al. suggest that this disease may be common, given the relatively frequent abnormal changes of the interspinous spaces.[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with Baastrup syndrome typically show an excessive lordosis. This results in mechanical pressure that can cause pain and repetitive strains combined with subsequent degeneration and collapse.[5], [13] Patients with Kissing Spine often complain about back pain, more specifically, midline pain that radiates distally and proximally, increasing on extension and reducing on flexion.[3] [5] This abnormal contact between adjacent spinous processes can lead to neoarthrosis and formation of an adventitious bursa. This can be seen pathologically on MRI. [1] [15] [16]

Other characteristics can be pain upon palpation at the level of pathologic interspinous ligament, oedema, cystic lesions, sclerosis, flattening and enlargement of the articulating surfaces and bursitis. Occasionally epidural cysts or midline epidural fibrotic masses can also occur [5]

Rotation and lateral flexion are usually painful with flexion being the least painful of all lumbar movements.[17] Baastrup’s disease can result in intraspinal cysts secondary to an interspinous bursitis which may, in rare cases, cause symptomatic spinal stenosis and neurogenic claudation [1]

Differential Diagnosis[3][18][edit | edit source]

- Lumbar Spondylosis

- Muscle Strain

- Spondylolisthesis

- Fracture of the spinous process

- Vertebral (e.g. lumbar) compression fractures

- Infectious etiologies of the spine

- Proliferative hyperostosis of the lumbar spinous processes

- Degenerative disease of the spine

- Cysts

- Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament

- Sclerotic bone metastases to spine

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

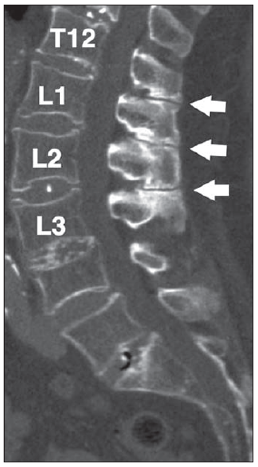

Baastrup Syndrome cannot be diagnosed by simply assessing the lumbar spine (see clinical examination), imaging modalities are required to prevent misdiagnosis. Numerous radiographic methods can be used to determine a diagnosis of Baastrup Syndrome. If necessary different methods can be combined for a more detailed picture of the degenerative and inflammatory signs at the level of interspinous ligament [5]

Computed Tomography CT-scan

Kissing Spine is diagnosed if 3 criteria appear on a CT scan: close approximation and contact between touching lumbar spinous processes with flattening and enlargement of the articulating surfaces and ending with reactive sclerosis of the superior and inferior fragments of adjacent processes.[1][5][19] CT scans can also report on detailed degenerative changes (e.g. facet joints hypertrophy, intervertebral disc herniation or spondylolisthesis).[5][19]

However, this type of diagnostic procedure is limited in the assessment of disc degeneration and soft tissue imaging, which means that interspinous bursae cannot be seen.[1]

Figure 3: CT scan of Baastrup Syndrome T12-L1-L2-L3 [1]

Radiography (X-rays)

X-rays are analogous to CT scans and show [5]

- Close approximation and contact of opposed spinous processes with sclerosis of the articulating surfaces;

- Expansion of the articulating surfaces or articulation of the two affected spinous processes;

- General degenerative changes in the spine.

X-rays have a lower cost, are more readily availability and give a relatively low ionising radiation dose. The disadvantage of radiographic imaging is poor imaging quality, in particular, at the lower lumbar fragments.

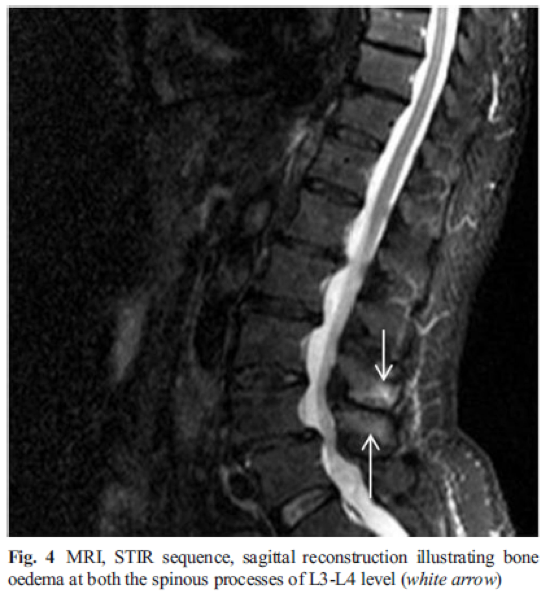

Magnetic Resonance Imaging MRI

In contrast to CT scans, an MRI may pick up on interspinous bursal fluid and a postero-central epidural cyst(s) at the opposing spinous processes.[20] lumbar interspinous bursitis is diagnosed where bursal fluid is present between 2 opposing affected spinous processes' (illustrated as a bright and/or high signal intensity areas on imaging) [15][21]

Similar to a CT scan MRI shows any flattening, sclerosis, enlargement, cystic lesions and bone oedema at the articulating surfaces of the spinous processes. This type of diagnostic procedure is extremely beneficial in determining whether there is a compression of the posterior thecal sac as an outcome of this contact of the interspinous processes.[21]

Further advantages of MRI imaging also include no ionising radiation and a highly detailed image at various levels (axial, coronal and sagittal).[5]

Figure 4: MRI scan of Baastrup Syndrome L3-L4 [1]

Baastrup’s Syndrome is regularly misdiagnosed and often incorrectly treated. A thorough clinically assessment and scrutinising of radiographic imaging are vital for an accurate diagnosis and to prevent mismanagement.[3]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The following tests can be used to objectively determine the progress and efficacy of treatment:

- Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale

- Visual Analogue Scale

- Oswestry

- Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire

- Measurements of spinal mobility:

- Fingertip-to-Floor (FTF) Test

- Modified Schober Test

Examination[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of Baastrup’s disease is verified with clinical examination as well as imaging studies.[5] Symptoms include low back pain with midline distribution that exacerbates when performing extension, relieved during flexion and is exaggerated upon finger pressure at the level of the pathologic interspinous ligament. Rotation and lateral flexion are also very painful. [5] The pain can be described as a sharp or deep ache, often worse during physical activities that increase lumbar lordosis or compression of these structures.[10]

Throughout the physical examination, the physiotherapist uses active and passive techniques with the intention of evoking complaints. Active spinal extension can reproduce the symptoms. The ‘stork test’ is very beneficial in the examination of this disease.[10] When the patient bends forward, relief is also gained.[17]

Figure 5: Stork Test

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The main goal of any therapy is to reduce the lower back pain as well as a return to normal ADLs. Medical treatment can be conservative or surgical intervention and an accurate diagnosis of the disease is necessary for determining appropriate treatment. Where an MRI shows active inflammatory changes or oedema, localised injections can be tried. If injections do not improve the patient's symptoms, surgical treatment is then recommended. [22]

Non-surgical treatment consists of localised injections of analgesics or NSAIDS.[5] which can be given bi-weekly. During this treatment period, extension movements of the lumbar spine should be avoided. [22] [23] After local anesthesia of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, the injection is given the painful interspinous ligaments between the affected spinous processes' under fluoroscopic control.[23] Okada et al. study suggested a positive result in the long term effects of injections of steroid and local anesthetics into the interspinous ligaments for the treatment of Baastrup's disease [23]

Suggested surgical therapies include: excision of the bursa, partial or total removal of the spinous process, or an osteotomy.[5] According to Franok S the average hospital stay is up to 31 days.[28] however, such invasive therapies occasionally have unsatisfactory outcomes and is has been reported that numerous patients have developed pain post-surgery.[5] It is also unclear whether surgery produces better results as an effective outcome has been reported in only 15 to 40 % of cases.[24]

A newer, alternative technique are interspinous spacer devices such as a X-STOP. [25] Zhou et al. describes it as; a floating device inserted into the interspinous process to increase the distance between the spinous processes and the intervertebral foramen. This procedure is more straight forward and is less invasive than the alternatives.[26]

Outcomes for use of the spacers showed post-operative improvements in the initial, short term follow up [26] but the long-term outcomes regarding the durability of symptomatic relief and complications specific to the implanted device are currently lacking and need further investigation. [27]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

As alluded to, the main goal is the reduction of pain as well as hyperlordosis and to improve spinal function. Once the pain is managed, physical therapy management can begin, involving education, strengthening and stretching of the abdominal and spinal muscles.[1] [24]

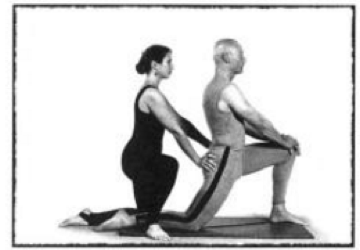

Treating the hyperlordosis is a key aspect, hence strengthening of the core muscles is recommended, along with postural education and hip flexor stretches. [28]

When the abdominal muscles are weak, the hip flexors are mainly responsible in shaping the lumbar spine.[29] Furthermore the rectus femoris muscle is a continuation of the hip flexor complex so it is important to stretch these muscles. The hip flexors can become shorter through long-term sitting or resting. When these muscles shorten, it can affect the function of the gluteal and the spinal muscles.[30]

The stretch below is one example of how to lengthen these muscles. Resting the weight on the knee and the front foot, push the hips forward until a stretch is felt, keeping the trunk upright. Maintain this position for at least 20 seconds, and repeat this 3-5 times on each side.[29]

Figure 6: Stretching the hip flexors [29]

Motion of the gluteus maximus muscle during the flexion-extension cycle is decreased in patients with chronic low back pain, which is why strengthening of this muscle should be part of the physical management program [31]

Physical therapy is also suggested to be helpful for reducing the neuromuscular damage that is provoked by the disease and other treatments such as, heat therapy, ergotherapy and muscle relaxation techniques can be helpful [1]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Kissing spines is characterised by the close approximation and contact of adjoining spinous processes'. It is often treated with injections as pain relief in the first instance. Physical therapy should include stretching and strengthening exercises to reduce the mechanical pressure on the spine and any hyperlordosis. Baastrup’s syndrome is still relatively unknown and is often misdiagnosed and consequently treated incorrectly. [20]

Baastrup syndrome is more common in the lumbar spine with L4-L5 being the most affected region.[5] People who are most likely to suffer from Kissing Spine are particularly elderly patients with a degenerative disc disease or hyperlordosis. Both of these conditions may lead to chronic contact between adjacent spinous processes. [32]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Kwong Y. et al., MDCT Findings in Baastrup Disease: Disease or Normal Feature of the Aging Spine?,American Journal of Roentgenology, 2011, 196(5):1156-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Kacki S. et al., Baastrup’s Sign (Kissing Spines): A neglected condition in paleopathology, International Journal of Paleopathology, 2011, 1(2): 104-110

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Singla A. et al., Baastrup’s disease: the kissing spine, World Journal of Clinical Cases, 2014, 2(2): 45-47.

- ↑ Yang A. et al., Kissing Spine and the Retrodural Space of Okada: More Than Just a Kiss?, University of Colorado, 2014, 6(3): 287-9.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 Filippiadis D.K. et al., Baastrup’s disease (kissing spines syndrome): a pictorial review, Springer, 2015, 6(1): 123–128

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Rajasekaran S. et al., Baastrup’s Disease as a Cause of Neurogenic Claudication: a case report, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003, 28(14): 273-275

- ↑ Rajasekaran S. et al., Baastrup’s Disease as a Cause of Neurogenic Claudication: a case report, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003, 28(14): 273-275

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Herkowitz H.N. et al., The Lumbar Spine, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, 85-87

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bogduk N., Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine, Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2012, 85-98

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 DePalma M.J., iSPINE Evidence Based Interventional Spine Care, Demos Medical, 2011, 4-8

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Masaracchio M. et al., Clinical Guide to Musculoskeletal Palpation, Human Kinetics, 2014, 203-208

- ↑ Han K-S., Biomechanical roles of spinal muscles in stabilizing the lumbar spine via follower load mechanism, ProQuest, 2008, 92-95.

- ↑ Jang E-C. et al., Posterior epidural fibrotic mass associated with Baastrup’s disease, Springer, 2010; 19(2): 165-168

- ↑ DePalma M.J. et al., What is the source of Chronic Low Back Pain and does age play a role?, Pain Medicine, 2011, 12: 224-233

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Maes R. et al., Lumbar Interspinous Bursitis (Baastrup Disease) in a Symptomatic Population: Prevalence on Magnetic Resonance Imaging, The Spine Journal, 2008, 33(7): 211-215

- ↑ FarinhaF. et al., Baastrup’s disease: a poorly recognized cause of back pain, ActaReumatol Port, 2015, 40:302-303

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hertling D. et al., Management of common musculoskeletal disorders: Physical Therapy Principles and Methods, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, 4th edition

- ↑ Kaye A.D. et al., Pain Management, Cambridge University Press, 2015

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 DePalma M.J. et al., Interspinous Bursitis in an Athlete, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 2004, 86: 1062-1064

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Chen C.K.H. et al., Intraspinal Posterior Epidural Cysts Associated with Baastrup's Disease: Report of 10 patients, American Journal of Roentgenology, 2004, 182(1): 191-194

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Clifford P.D. et al., Baastrup Disease: Imaging Series, The American Journal of Orthopedics, 2007, 36(10): 560-561

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lamer T.J. et al., Fluoroscopically-Guided Injections to Treat “Kissing Spine” Disease, Pain Physician, 2008; 11: 549-554

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Okada K. et al., Interspinous Ligament Lidocaine and Steroid Injections for the Management of Baastrup’s Disease : A case Series, Asian Spine Journal, 2014 ; 8(3) : 260-266

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Cohen S.T. et al., Management of Low Back Pain, British Medical Journal, 2008, 338: 100-106

- ↑ Yue J.J. et al., Motion Preservation Surgery of the Spine, Elsevier - Health Sciences Division, 2008, 816 pagina’s

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Zhou D. et al., Effects of Interspinous Spacers on Lumbar Degenerative Disease, Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 2013, 5: 952-956

- ↑ Chao S. et al., Interspinous Process Spacer Technology, Techniques in Orthopaedics, 2011, 26(3): 141-145

- ↑ Scannell J.P. et al., Lumbar posture--should it, and can it, be modified? A study of passive tissue stiffness and lumbar position during activities of daily living, 2003, 83(10): 907-917

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Laughlin K., Overcome Neck and Back Pain, Simon & Schuster, 1998, 58-61

- ↑ Ross M., Stretching the Hip Flexors, National Strength & Conditioning Association, 1999, 21(3): 71-72

- ↑ Leinonen V. et al., Back an Hip Extensor Activities During Trunk Flexion/Extension: Effects of Low Back Pain and Rehabilitation, American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 200, 81: 32-37

- ↑ Pinto P.S. et al., Spinous Process Fractures associated with Baastrup disease, Clinical Imaging, 2004, 28(3): 219-222