Atelectasis

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Atelectasis describes a state of the collapsed and non-aerated regions of the lung parenchyma[1]. It results from the partial or complete, reversible collapse of the small airways leading to an impaired exchange of CO2 and O2 - i.e., intrapulmonary shunt.

- It is most commonly seen in the post-operative patients whose breathing mechanism is impacted by the procedure, pain, and prolonged recumbency. The incidence of atelectasis in patient's undergoing general anesthesia is 90%.[2]

- Less commonly, atelectasis is seen in people with conditions signify chronic sputum production or airway obstruction, such as COPD, bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Atelectasis does not preferentially affect either sex.

- There is also no increased incidence of atelectasis in patients with COPD, asthma, or increased age.

- It is more common in patient's who recently underwent general anesthesia, with the incidence being as high as 90% in this patient population.

Research has shown that atelectasis appears in the dependent regions of both lungs within five minutes of induction of anesthesia.

- Atelectasis is more prominent after cardiac surgery with cardio-pulmonary bypass than after other types of surgery, including thoracotomies; however, patients undergoing abdominal and/or thoracic procedures are at increased risk of developing atelectasis.

- Obese and/or pregnant patients are more likely to develop atelectasis due to cephalad displacement of the diaphragm[2]

Common types of atelectasis[edit | edit source]

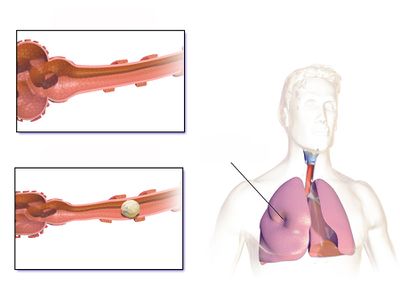

Atelectasis can be divided into two main types, obstructive and non-obstructive atelectasis.

Obstructive atelectasis[3][1]: causes by blockage of the airway or multiple airways which limits airflow to the alveoli resulting collapse of the lung. It can arise due to

- Intrinsic factors such as mucus plug (cystic fibrosis, asthma, bronchiectasis, pneumonia...), polyps, papilloma, adenoma.

- Extrinsic factors such as foreign body, recurrent aspiration, and histoplasmosis

This type of atelectasis happens with acute pneumonia and chronic sputum production. Other conditions, such as malignancy and COPD, which impact on the patency of the airway can also cause obstructive atelectasis.

Obstruction atelectasis can impact parts of the lung or the entire depending on the location of the blockage. For example, when obstruction locates higher up or in bigger airways, a larger area of the lung would be affected due to the anatomy of the lung.

Non-obstructive atelectasis[4][5][6][7][8]: is an umbrella term for other types that do not involve blockage of the airways. For example, compressive atelectasis, post-surgical atelectasis, round atelectasis, adhesive atelectasis, and replacement atelectasis. Amongst those, physiotherapy interventions can only be effective in treating compressive and post-surgical atelectasis.

- Passive atelectasis: results when the natural tendency of lung tissue to collapse due to elastic recoil goes unstopped, due to loss of the negative pressure in the neural space. For example atelectasis due to pneumothorax.

- Compressive atelectasis: Sometimes is classified as a subtype of passive atelectasis. When there is an external force acting on the lung tissue preventing alveoli from expanding, such as pleural effusion.

- Post-surgical atelectasis: Usually due to the impaired breathing pattern due to post-operative pain. Other contributing factors including effects of anesthetics, type of surgery (usually abdominal or chest surgery), history of smoking, high BMI, prolonged recumbency, and increased sputum production.

- Adhesion atelectasis occurs due to surfactant deficiency, which can be seen in hyaline membrane disease in children and on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Surfactant deficiency or dysfunction, the pulmonary surfactant, secreted by pneumocytes type II, covers the alveolar surfaces and it is composed of phospholipids, lipids, surfactant specific proteins, and calcium. The surfactant can modify alveolar tension with changes in the lung volumes, by reducing the alveolar surface tension, surfactant stabilizes the alveoli and prevents collapse. Therefore deficiency or dysfunction could result in the collapse of the alveolar space.

- Cicatrizion atelectasis is seen in fibrosis, the alveoli collapse due to the contraction of the scarred tissue.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of atelectasis are often non-specific:[1][9]

- Chest pain

- Shallow breathing pattern

- Reduced chest expansion

- Increased respiratory rate

- Increased work of breathing

- Reduced breath sound on the ipsilateral side of auscultation. In cases of the upper lobe atelectasis, bronchial sounds may be heard, because of the proximity to the major airways.

- Hypoxia/hypoxemia

Once the diagnosis of atelectasis is suspected chest x-rays using anterior-posterior projections need to be performed to document the presence, extent, and distribution of atelectasis.

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Most atelectasis that appears during general anesthesia leads to transient lung dysfunction that resolves within 24 hours after surgery. Nevertheless, some patients develop significant perioperative respiratory complications that can lead to increased morbidity and mortality if not treated.

- Atelectasis is preventable through avoidance of general anesthesia, early mobilization, adequate pain control, and minimizing parenteral opioid administration.

- Changing position from supine to upright increases FRC and decreases atelectasis.

- Encouraging patients to take deep breaths, early ambulation, incentive spirometry, use of Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Device, chest physiotherapy, tracheal suctioning (in intubated patients), and/or positive pressure ventilation has been shown to decrease atelectasis.

- Prophylactic measures, such as incentive spirometry, should be taught and instituted before surgery and continued on an hourly basis following surgery until discharge to obtain the maximal benefit[2].

- As atelectasis can be caused by blockage of bigger airways, physiotherapy treatment to assist in airway clearance can improve atelectasis

- Example of airway clearance technique: active cycle breathing techniques[10][11], supported cough[11], positioning[10], postural drainage[10]

Breathing exercises:

- Incentive spirometry can be useful for treating or preventing atelectasis in post-operative patients, it gives visual feedback to the patient on how he is performing. Consists of a deep and slow maximal inspiration, through the mouth, followed by a post-inspiratory pause and exhalation up to functional residual capacity[12].

- Sustained maximal inspiration (SMI): is the same as incentive spirometry but it does not require material [12]. SMI is often used to prevent and manage atelectasis in abdominal and thoracic surgery patients.[13] Its effects are often compared with incentive spirometry, and interestingly evidence has shown similar effects in SMI in improving breathing patterns, chest expansion, and thoracoabdominal asynchrony.[12] Hence, it could be an alternative where incentive spirometry is unavailable.

Early mobilization[10][14][15]

This fits in the picture of both post-operative patients and populations with acute respiratory conditions, such as acute pneumonia. When a patient is medically stable enough, the physiotherapist should assist with mobilization in accordance with the patient's status. Early mobilization, includes sitting position and ambulation either with/without aids (onset <48h after surgery). It is believed that early mobilization results in increased lung volume, preventing therefore of atelectasis.

Complications[edit | edit source]

Atelectasis is one of the most common respiratory complications in the perioperative period, and it may contribute to significant morbidity and mortality, including the development of pneumonia and acute respiratory failure. Prevention of atelectasis is vital to improving patient outcomes in the postoperative period. Despite employing these strategies, atelectasis is not always preventable and, therefore, early recognition and treatment are equally important.[2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Peroni DG, Boner AL. Atelectasis: mechanisms, diagnosis and management. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2000;1:274-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Grott K, Dunlap JD. Atelectasis. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Aug 10.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545316/#!po=10.0000 (accessed 18.4.2021)

- ↑ Raman TS, Mathew S, Garcha PS. Atelectasis in children. Indian pediatrics. 1998 May;35(5):429-35.

- ↑ Culiner MM. The right middle lobe syndrome, a non-obstructive complex. Diseases of the Chest. 1966; 50(1):57-66.

- ↑ Sutnick AI, Soloff LA. Atelectasis with pneumonia: a pathophysiologic study. Annals of internal medicine. 1964;60:39-46.

- ↑ Al-Tubaikh J.A. Pulmonology. In: Internal Medicine. Springer, Cham 2017.p. 273-325.

- ↑ Magnusson L, Spahn DR. "New concepts of atelectasis during general anaesthesia." BR J Anaesth. 2003;91.1: 61-72.

- ↑ Woodring J H, & Reed JC . Types and mechanisms of pulmonary atelectasis. J Thorac Imag 1996;11:92-108.

- ↑ Duggan M, Kavanagh BP. Atelectasis in the perioperative patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:37-42.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Stiller K, Geake T, Taylor J, Grant R, Hall B. Acute lobar atelectasis: a comparison of two chest physiotherapy regimens. Chest. 1990 Dec 1;98(6):1336-40.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Schindler MB. Treatment of atelectasis: where is the evidence?. Critical Care. 2005 Aug;9(4):341.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Mendes LP, Teixeira LS, da Cruz LJ, Vieira DS, Parreira VF. Sustained maximal inspiration has similar effects compared to incentive spirometers. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2019 Mar 1;261:67-74.

- ↑ Tan AK. Incentive spirometry for tracheostomy and laryngectomy patients. The Journal of otolaryngology. 1995 Oct;24(5):292-4.

- ↑ Possa SS, Amador CB, Costa AM, Sakamoto ET, Kondo CS, Vasconcellos AM, et al. Implementation of a guideline for physical therapy in the postoperative period of upper abdominal surgery reduces the incidence of atelectasis and length of hospital stay. Rev Port Neumol 2014;20(2): 69-77.

- ↑ Moradian ST, Najafloo M, Mahmoudi H, Ghiasi MS. Early mobilization reduces the atelectasis and pleural effusion in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomized clinical trial. J Vasc Nurs 2017;35(3):141–145.