Meniscal Repair

3Original Editor - Rachael Lowe, Jennifer Uytterhaegen

Top Contributors - Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Admin, Van Horebeek Erika, Scott Cornish, Kim Jackson, David Bayard, Lauren Heydenrych, Yannick Goubert, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, Wanda van Niekerk, Mahbubur Rahman and George Prudden David Bayard, Neil De Heyder, Jack Cortvriend, Nicolas Casier

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

An arthroscopic meniscectomy is a procedure to remove some or all of a meniscus from the tibio-femoral joint of the knee using arthroscopic (keyhole) surgery. The procedure can be a complete meniscectomy where the meniscus and the meniscal rim is removed or partial where only a section of the meniscus is removed. This may vary from a minor trimming of a frayed edge to anything short of removing the rim. This is a minimally invasive procedure often carried out as an outpatient in a one-day clinic [1] and is performed when a meniscal tear is too large to be corrected by a surgical repair of the meniscus. [1] Where non-operative therapy provides some degree of symptom relief over the long-term, these benefits may become increasingly ineffective as the affected meniscus degenerates over time. In such cases, partial arthroscopic meniscectomy can be more effective in improving patient quality of life.

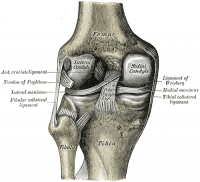

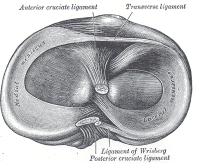

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The menisci of the knee are crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structures which add to the tibio-femoral joint congruency while also dispersing friction and body weight. A difference exists between the medial and the lateral meniscus: [1]

- The medial meniscus is larger and has a C type shape. It blends with the medial collateral ligament [2]

- The smaller lateral meniscus has an O shape. This is more mobile than the medial meniscus and blends with the popliteus muscle. [2]

Epidemiology/ Etiology[edit | edit source]

Majewski reports that injuries to the menisci are the second most common injury to the knee, with an incidence of 12% to 14% and a prevalence of 61 cases per 100,000 persons [3][4][5]. In his epidemiological study conducted on 17,397 patients, football, followed by skiing, are the 2 sports with an increased risk of meniscal injuries. Amongst injuries affecting the knee, he suggests that most involve the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the medial and lateral meniscus. He also observed that 85% of patients with meniscal and ACL injuries require arthroscopic treatment [6].

Etiology

For degenerative meniscal tears, this literature review provides strong evidence that age (greater than 60 years), gender (being male), work-related kneeling and squatting, and consistently climbing stairs of greater than 30 flights are risk factors for meniscal tears. There was also strong evidence that sitting for longer than 2 hours per day may reduce the risk of degenerative meniscal tears. For acute meniscal tears, the evidence suggested that playing football and rugby are high risk factors [7]. Barbara et al suggest that waiting more than 12 months between ACL injury and reconstructive surgery is a risk factor for developing a tear of the medial meniscus [8] [9].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Joint line tenderness and effusion

- Complaints of 'clicking', 'locking' and 'giving way' are common

- Functionally unstable knee [1]

- Symptoms are frequently more intense by flexing and loading the knee, with activities such as squatting and kneeling being poorly tolerated because of stiffness and pain [10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Joint line tenderness may present a false positive as other diagnosis' may be; osteoarthritis, osteochondral defects, collateral ligament injury or fractures. [11] Effusion may also occur when there are problems with the cruciate ligaments, bones or the articular cartilage.

Pathologies such as chondromalacia patellae, fractures and Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome can share the same symptoms of increased pain on knee flexion, loading the knee, squatting and kneeling.

A sensation of giving way is not unique to meniscal damage, but also in patients an anterior cruciate ligament injury. The feeling of instability and locking is also common with osteochondritis dessecans.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

1. Joint line tenderness has been reported to be the best common test for meniscal injury [1]

2. McMurray's test is positive if an audible pop or a snap is heard at the joint line whilst flexing and rotating the patient's knee.

3. Appley's test is performed with the patient prone, then hyper-flexing the knee and rotating the tibial plateau on the femoral condyles.

4. Steinman's test is performed on a supine patient by bringing the knee into flexion and rotation.

5. Ege's Test is performed with the patient squatting. A positive result is an audible and palpable click heard/felt over the area of the meniscus tear. The patient's feet are turned outwards to detect a medial meniscus tear, and turned inwards to detect a lateral meniscus tear.

6. Thessaly Test.

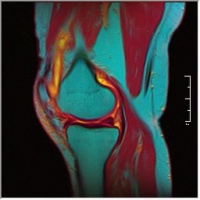

7. MRI: has a crucial role in patients with combined injuries and the assessment of the meniscal surfaces. Abnormal findings include: [12]

- Grade I: Discrete central degeneration - an intra-meniscal lesion of increased signal without connection to the articular surface [13]

- Grade II: Extensive central degeneration - a larger intra-meniscal area of increased signal intensity, again without connection to the articular surface. May be horizontal or linear in orientation [13]

- Grade III: Meniscal tear - increased intra-meniscal signal intensity with contour disruption of articular surface. May be associated with displacement of meniscal fragments or superficial step formation [13]

- Grade IV: Complex meniscal tear - multiple disruption of meniscal surfaces

The presence of tears in the red area versus the white areas of the meniscus is crucial as long term positive prognosis for the repair of tears is only good within the vascularised areas. [13]

| [14] | [15] |

Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31mbTI4CsUI

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVXDEAYPYCg

File:Knee MRI.jpg T1 Weighted MRI |

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET)

Numeric Rating Scale for pain (NRS)

Visual Analogue Scale for pain (VAS)

Knee outcome survey (KOS)

Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)

International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC)

Tegner Lysholm knee scoring score [16]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Indication for surgery

This decision is based on several factors such as age, co-morbidities, compliance, tear characteristics (location of the tear, age and pattern of the tear) and whether the tear is stable or unstable. Where the tear is deemed to be unstable surgery is necessary. [17] [18]

Degenerative or non-degenerative tears which are asymptomatic or stable are treated non-surgically. but treated surgically in symptomatic cases [19]

It has then to be determined whether meniscal repair or a meniscectomy is appropriate. Where none of the normal surgical treatments are appropriate total meniscectomy is the option. The factors taken in consideration are:

- the clinical evaluation

- related lesions

- the exact type, location, and extent of the meniscal tear [20]

If a meniscal repair is performed with concomitant ACL reconstruction the success rate has reported to have been elevated in several studies [21] [22] [23] [24]

Tenuta JJ et al. also found that rim width is an important factor as no repair with a width greater than 4 mm healed [25]

Small, degenerative meniscal tears are often treated conservatively with rest, NSAIDS, reducing load bearing on the joint through activity modification and treating with physical therapy. Where a non-surgical approach is taken it is essential that a good level of strength is achieved and maintained in the affected leg and activities requiring pivoting or sudden changes of direction are avoided. .

If the tear is large, in a low vascularised region or if conservative management fails to alleviate the associated pain and joint dysfunction then surgery is the next step [26].

Surgery

Two small incisions are made in the anterior region of the knee below the patella. A camera is inserted through one of the incisions so that the surgeon can see the inside of the knee joint on a monitor. The other incision is used to place a tool into the joint that will clip and remove the torn piece of cartilage. While the camera is inside the joint the surgeon uses this opportunity to examine the rest of the knee to make sure it is otherwise healthy.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Pre-Operative[edit | edit source]

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) causes muscle contraction by applying transcutaneous current to terminal branches of the motoneuron. In subjects with knee osteoarthritis, NMES can increase quadriceps strength and improve functional performance, and has been found to be as effective as exercise therapy. NMES has also a beneficial effect on muscle mass. Other benefits of the therapy are a reduction in postoperative muscle atrophy with exercise prehabilitation [27]

Pre-operative risk factors

Meniscectomy is a safe procedure even in older patients. However, regardless of age, patients with an increased comorbidity and those with a history of smoking are at increased risk of adverse events and/or readmission after the procedure. [6]

Post-Operative[edit | edit source]

After meniscectomy rehabilitation protocol can be aggressive, because in the knee joint anatomical structure should not be protected during the healing phase. The rehabilitative treatment consists of ice-ultrasound therapy, friction massage, joint mobilisation, calf raises, steps-ups, extensor exercise and bicycle ergometry[28] Treatment under water cannot begin until wounds have properly closed in order to prevent increased risk of infection.

In the first week after surgery rehabilitation treatment consists of a progressive loading with crutches. Early objectives after surgery are: control of pain and swelling, maximum knee range of motion (ROM) and a full weight bearing walking. There is no load limitation, with weight bearing being as tolerated by the patient.

In the subsequent 3 weeks the goal is to normalise gait and to increase knee ROM, led by the patient’s tolerance. Intensive muscle strengthening, proprioceptive and balance exercises are carried out around the third week.

Return to sport/activities is recommended only when the quadriceps’ muscle strength is at least 80% of the contralateral limb. Competitive level sport how ever is not recommended until the muscle strength in the operated limb is at least 90%.

In general, patients return to work after 1 to 2 weeks, to sporting activities after 3 to 6 weeks and to competition after 5 to 8 weeks [28]

Rehabilitation can be split into 3 phases

• Phase 1: The Acute Phase (1-10 days post-op)

In the first phase, the goals are to decrease inflammation, restore the range of motion and the neuromuscular re-education of the quadriceps. Recommended exercises in the first phase are: long arc quadricep, short arc quadricep, hamstring curls (open chain exercises) and bicycle training, leg presses (Closed chain exercises).

• Phase 2: The Subacute Phase (10 days-4 weeks post-op)

Goals are to restore muscle strength and endurance, to re-establish full and pain free ROM, a gradual return to functional activities and to minimise normal gait deviations. More concentric/eccentric exercises for the hip and the knee should be added to the open chain exercises from phase 1. Closed chain exercises in the second phase should be resisted terminal knee extension, partial squats (not complete), step up/down progressions, toe raises, functional and agility training.

• Phase 3: The Advanced Activity Phase (4-7 weeks post-op)

The goals of the third and last phase are to enhance muscle strength and endurance, maintain full ROM and a return to sports or full functional activities. This phase is based on progression to dynamic single leg stance, plyometrics, running, and sport specific training.

Rehabilitation Overview[edit | edit source]

- Control the pain, swelling and inflammation by using: cryotherapy, analgaesics, NSAIDs. [13] As rehabilitation progresses, continued use of modalities may be required to control residual pain and swelling. [29]

- Restore range of motion using exercises within the limits specified by the surgeon [13] If a meniscal repair has been performed, extreme flexion and rotation should be limited until the wound in the meniscus has healed (8 to 12 weeks).

- Restore muscle function using targeted strengthening exercises for the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip. Examples: [13][2] Strengthening around the knee is crucial, but it is also necessary to re-establish proximal stability and strength if weight-bearing was restricted pre- or post-operatively.

- Flexibility should also be included in the reahbilitation programme

- Optimisation of neuromuscular coordination and proprioceptive re-education. [13]

- The extent and progression of the exercises is determined by the patient, the physical therapist and the surgeon [29]

- Progressive weight-bearing and joint stress are necessary to enhance the functionality of the meniscal repair and should be progressed as indicated by the surgeon and patient tolerance [13]

Additional Considerations[edit | edit source]

| [30] |

- Full weight bearing as tolerated immediately after the meniscectomy, although crutches may be required for 2-5 days until the patient is able to fully weight bear without significant discomfort

- Passive and active ROM exercises begin immediately post-operatively in combination with quadriceps strengthening exercises

- Return to full ADLs usually at 4-6 weeks, provided full ROM has been restored

- Athletes may return to full athletic activities when normal quadriceps muscle strength has recovered and active ROM is full and pain-free

- EMG-B (electromyography-biofeedback) is an effective treatment in improving quadriceps muscle strength after arthroscopic meniscectomy surgery [2]

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

Raine Sivhonen et al., ‘a protocol for a randomised, placebo surgery controlled trial on the efficacy of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for patients with degenerative meniscus injury with a novel ‘RCT within-a-cohort’ study design.’, CMAJ, 2014 Oct 7; 186(14): 1057–1064.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Brindle T, Nyland J, Johnson DL. The meniscus: review of basic principles with application to surgery and rehabilitation. J Athl Train. 2001;36(2):160-169.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation is to restore patient function based on individual needs. It is important to consider:

- the type of surgical procedure

- the post-surgical protocol determined by the surgeon [31]

- which meniscus was repaired

- the type of meniscal tear

- preoperative knee status (including time between injury and surgery)

- decreased range of motion or strength

- the patient's age

- the presence of coexisting knee pathology (particularly ligamentous laxity or articular cartilage degeneration)

- the patient's functional and/or athletic expectations and motivations

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 McKeon B, Bono J, Richmond J, editors. Knee arthroscopy. London:Springer, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Atkinson HDE, Laver JM, Sharp E. Physiotherapy and rehabilitation following soft tissue surgery of the knee. Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(2):129-138.

- ↑ Logerstedt DS, et al. Knee pain and mobility impairments: meniscal and articular cartilage lesions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(9):597

- ↑ Baker BE, Peckham AC, Pupparo F, Sanborn JC. Review of meniscal injury and associated sports. Am J Sports Med

- ↑ Hede A, Jensen DB, Blyme P, Sonne-Holm S. Epidemiology of meniscal lesions in the knee. 1,215 open operations in Copenhagen 1982-84. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990.

- ↑ Majewski M, Habelt S, Klaus Steinbruck. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. Knee. 2006;13(3):184–188.

- ↑ Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Abram F, Raynauld JP, Cicuttini F, Jones G, Meniscal tear as an osteoarthritis risk factor in a largely non-osteoarthritic cohort: a cross-sectional study

- ↑ Barbara A.M. Snoeker, 1, Eric W.P. Bakker, 1, Cornelia A.T. Kegel, 2, Cees Lucas, 1,Risk Factors for Meniscal Tears: A Systematic Review Including Meta-analysis, Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2013 Volume:43 Issue:6 Pages:352–367,

- ↑ Church S, Keating J, Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: timing of surgery and the incidence of meniscal tears and degenerative change, J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005 Dec; 87(12): 1639–1642.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMeserve - ↑ Konan S, Rayan F, Sami F, Haddad, Do physical diagnostic tests accurately detect meniscal tears? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009 Jul; 17(7): 806–811

- ↑ Teller P, Konig H, Weber U, Hertel P. MRI atlas of orthopedics and traumatology of the knee. London:Springer, 2003.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTeller - ↑ CRTechnologies. Steinman I Sign Test (CR). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31mbTI4CsUI[last accessed 15/12/12]

- ↑ CRTechnologies. Ege's Test (CR). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVXDEAYPYCg[last accessed 15/12/12]

- ↑ Karen K. Briggs, Mininder S. Kocher, William G. Rodkey J, Steadman R, Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm knee score and Tegner activity scale for patients with meniscal injury of the knee, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006 Apr; 88(4): 698–705

- ↑ Sherif A. Ghazaly, Amr A. Abdul Rahman, Ahmed H. Yusry, Mahmoud M. Fathalla, Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is superior to physical rehabilitation in the management of symptomatic unstable meniscal tears, International Orthopaedics, 2015, Volume 39, Number 4, Page 769

- ↑ Simon C et al. Treatment of meniscal tears: An evidence based approach. World Journal of Orthopedics. Juli 2014. 5(3): 233-241

- ↑ DeHaven Ke. Decision-making factors in the treatment of meniscus lesions. Clinical Orthopedics & Related Research 1990; (252) 49-54

- ↑ Jensen NC, Riis J, Robersten K, et al. Arthroscopic repair of the ruptured meniscus: one to 6.3 years follow up. Arthroscopy 1994; 10 (2): 211-214

- ↑ Tenuta JJ, Arciera RA. Arthroscopic evaluation of meniscal repairs. Factors that effect healing. Am J Sports Med 1994; 22 (6): 797-802

- ↑ Cannon WD, Jr., Vittori JM. The incidence of healing in arthroscopic meniscal repairs in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees versus stable knees. Am J Sports Med 1992; 20 (2) 176-181.

- ↑ Walter RP, Dhadwal AS, Schranz P, Mandalia V. The outcome of all-inside meniscal repair with relation to previous anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 21 (6), 1156-1159.

- ↑ Konan S, Rayan F, Haddad FS., Do physical diagnostic tests accurately detect meniscal tears?, Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthosco,Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009 Jul;17(7):806-11

- ↑ Tenuta JJ, Arciera RA. Arthroscopic evaluation of meniscal repairs. Factors that effect healing. Am J Sports Med 1994; 22 (6): 797-802

- ↑ MESSNER K, GAO J. The menisci of the knee joint. Anatomical and functional characteristics, and a rationale for clinical treatment. Journal of Anatomy. 1998;193(Pt 2):161-178.

- ↑ Raymond J wall et al.” Effects of preoperative neuromuscular electrical stimulation on quadriceps strength and functional recovery in total knee arthroplasty. A pilot study” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2010 11:119

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Frizziero A, Ferrari R, Giannotti E, Ferroni C, Poli P, Masiero S. The meniscus tear: state of the art of rehabilitation protocols related to surgical procedures. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2012;2(4):295-301.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Thomson LC, Handoll HH, Cunningham A, Shaw PC. Physiotherapist-led programmes and interventions for rehabilitation of anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament and meniscal injuries of the knee in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD001354.

- ↑ MegaElectronicsLtd. Biofeedback rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction (eMotion Biofeedback). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQYo8B8wKWc[last accessed 15/12/12]

- ↑ Kohn D, Aagaard H, Verdonk R, Dienst M, Seil R. Postoperative follow-up and rehabilitation after meniscus replacement. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9(3):177-80.fckLR