Ankle Lateral Ligament Injury Assessment

Original Editor - Mariam Hashem

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Jess Bell and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Lateral ankle ligament injury is a common MSK condition representing 85% of ankle injuries [1]and has a high recurrence rate[1]. Persisting post-injury symptoms such as swelling, impaired strength, instability (occasional giving way), and impaired balance responses for more than 12 months following the initial injury is defined as '' Chronic Ankle Instability-CAI''[2]. Up to 70% of patients report developing chronic ankle instability[3].

Limited dorsiflexion[4], reduced proprioception, reduced isometric abductor hip strength[5], postural control deficiencies on SLS [6] were associated with higher risk of ankle sprain and instability.

The highest incidence of LAS was found for aeroball, basketball, indoor volleyball, field sports and climbing[7].

A systematic review by Hiller et al[8] reported greater larger talar curve, reduced concentric inversion strength, greater sway when standing on stable surfaces with eyes closed, a more inverted ankle position and decreased foot clearance during gait, and prolonged time to stabilization after a jump.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

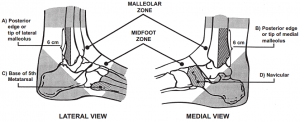

The Ottawa Ankle Rules are used to determine the need for radiographs in acute ankle injuries. If these rules were positive, the patient/athlete needs an x-ray to rule out fractures.

These rules are as follows:

1-Tenderness on palpation of :

A-posterior edge/dip of lateral malleolus

B-Posterior edge/dip of medial malleolus

C-Base of 5th metatarsal

D-Navicular bone

2-Inability to fully weight-bear for normal 4 steps at time of injury or on examination

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Mechanism of Injury and WB status. If an athlete was injured during a game, a decision has to be made on return to play based on the MOI and WB status.

- Mechanical and postural contributing Factors

- When acute symptoms subside, the Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool can be used to predict the developmenet of CAI. A cut off of higher than 11.5 is unlikely to progress to CAI. A lower score is more likely associated with higher risk of developing CAI[9].

Objective Assessment:[edit | edit source]

- Assessment of ligamentous laxity:

- Swelling

- Isometric ankle eversion/abduction

Chronic ankle instability checklist:[edit | edit source]

Following LAS, a comprehensive assessment of the factors contributing factors can help predict the prognosis. The following is a set of markers that are associated with CAI:

ROM markers:

Weight-bearing ankle Dorsiflexion < 34 degrees

Strength markers:

Isometric hip abduction strength <34% of body weight

Balance-stability markers:

Single-leg balance test <10 seconds and balancing on toes < 5 seconds without unsteadiness.

Poor performance on the Star Excursion Balance Test. SEBT.[10].

Performance markers:

Unable to complete single leg drop landing test.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Roos KG, Kerr ZY, Mauntel TC, Djoko A, Dompier TP, Wickstrom EA. The epidemiology of lateral ligament complex ankle sprains in National Collegiate Athletic Association sports. American journal of sports medicine. 2016.The American Journal of Sports Medicine Vol 45, Issue 1, pp. 201 - 209

- ↑ Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, editor. Manual therapy for musculoskeletal pain syndromes: An evidence-and clinical-informed approach. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015 Jun 17

- ↑ Anandacoomarasamy A, Barnsley L. Long term outcomes of inversion ankle injuries. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:e14; discussion e14.

- ↑ Pope R, Herbert R, Kirwan J. Effects of ankle dorsiflexion range and pre-exercise calf muscle stretching on injury risk in Army recruits. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 1998 Jan 1;44(3):165-72.

- ↑ Powers CM, Ghoddosi N, Straub RK, Khayambashi K. Hip strength as a predictor of ankle sprains in male soccer players: a prospective study. Journal of athletic training. 2017 Nov;52(11):1048-55.

- ↑ Kobayashi T, Yoshida M, Yoshida M, et al. Intrinsic Predictive Factors of Noncontact Lateral Ankle Sprain in Collegiate Athletes: A Case-Control Study. Orthop J SportsMed 2013;1:232596711351816.

- ↑ Waterman BR, Belmont PJ, Cameron KL, et al. Epidemiology of ankle sprain at the United States Military Academy. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:797–803.

- ↑ Hiller CE, Nightingale EJ, Lin CW, Coughlan GF, Caulfield B, Delahunt E. Characteristics of people with recurrent ankle sprains: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2011 Jun 1;45(8):660-72.

- ↑ Vuurberg G, Kluit L, van Dijk CN. The Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool (CAIT) in the Dutch population with and without complaints of ankle instability. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2018 Mar 1;26(3):882-91.

- ↑ Gribble PA, Hertel J, Plisky P. Using the Star Excursion Balance Test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. Journal of athletic training. 2012 May;47(3):339-57.