An Overview of Physiotherapy in UK Prisons

Original Editor - Andrea Beznaczuk-Smyrnew, Mark Chawke, Niamh Coveney, Anthony Gorsek, Jo Hampton, Katie McGregor as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Andrea Beznaczuk-Smyrnew, Anthony Gorsek, Mark Chawke, Kim Jackson, Katie McGregor, Niamh Coveney, Admin, Jo Hampton, George Prudden, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Olajumoke Ogunleye and 127.0.0.1

Introduction [edit | edit source]

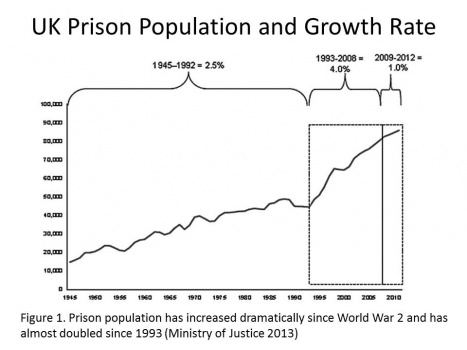

Physiotherapy is a constantly evolving role in United Kingdom’s health care system. An emerging role for physiotherapists is working within prisons to treat prisoners. The CSP (Chartered Society of Physiotherapy) brought this to the forefront with an article about rising COPD rates in prisons in England and Wales and the implications for treatment . Another factor that may be contributing to the emergence of this role is that the number of prisoners in the UK has almost doubled since 1993 [1],[2] further indicating that physiotherapists may need to become more involved in providing health care in prisons.

However, just like any new treatment setting, there may be a few things that a physiotherapist should be aware of before providing treatment to prisoners. The aim of this page is to provide useful information for students and registered physiotherapists, as well as other allied health care professionals who will be or may be asked to treat prisoners in both outpatient clinics and in prisons. Additionally, a basic understanding of why this is an emerging role in physiotherapy, what to expect when you are about to treat a prisoner, an overview of the ethics and policies that effect physiotherapy treatments in prison, the barriers and facilitators of treating a prisoner, and some general advice from physiotherapists currently treating prisoners will be also be presented. The Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) standards of proficiency for physiotherapists (2013) state that physiotherapists must be able to practise within the legal and ethical boundaries of our profession[3]. This involves understanding the need to act in the best interests of service users at all times. Regardless of their background, prisoners are entitled to healthcare like any other UK citizen and as physiotherapists we may have an active role in providing this.

Video: Prison Healthcare Service [4]

Due to the confidential nature of the topic, much of the information gathered for this page was obtained from various interviews with qualified physiotherapists in NHS Scotland. To respect their anonymity, please note that (*) denotes information recorded from these interviews. The following provides a brief descriptive of each interviewed physiotherapist:

- Physiotherapist A: interviewed 18th October, 2013, answers to questions were received via email, Community Physiotherapist who, in addition to her regular caseload, is also responsible for treating prisoners in up to three prisons in Scotland.

- Physiotherapist B: interviewed 8th November 2013, face-to-face interview at a health centre, Band 7 MSK Physiotherapist, approximately 3 years experience working 3.25 hours x 1 day per week in a Scottish prison.

- Physiotherapist C: interviewed 14th November 2013, phone interview, Band 6 Community Physiotherapist, treats one patient in a Scottish prison 1 day per week for approximately 5 months.

- Physiotherapist D: interviewed 21st November, 2013, face-to-face interview at a health centre, Team Lead Physiotherapist - MSK Specialist, previously worked in Scottish Prisons for approximately 10 years (until 2011) as an MSK Physiotherapist, 6 hours x 1 day per week.

Learning Outcomes [edit | edit source]

1. Identify and justify the knowledge, skills and values required by physiotherapists to deliver effective healthcare in prisons.

2. Recognise common medical conditions encountered by prisoners, and interpret the physiotherapist's role in treatment.

3. Report and analyse barriers encountered by physiotherapists in providing treatment to prisoners.

4. Synthesise the presented information to enhance your knowledge of the physiotherapy service in UK prisons.

Current Prison Statistics[edit | edit source]

According to the Scottish Prison Service, there are currently 18 prisons in Scotland with a total of 7801 prisoners in custody and a further 353 in home detention[5].This equates to a total of 8154 prisoners, and the BBC News state that this figure is expected to rise to around 9,500 within the next decade[6]. In 2012, the number of long term prisoners (those sentenced to four years or greater) in Scotland was 2326. The prison population of England and Wales combined equalled 84,052 when recorded earlier this year [7].This has increased by almost 98% from June 1993 to June 2012 due to increased sentences being issued and prisoners staying in prison for longer. [2]

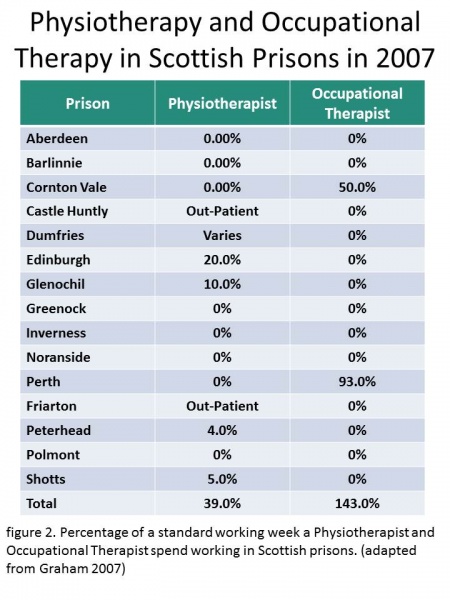

In 2005, there were 0.39 physiotherapists per prison in Scotland (based on a 40 hour week) with six prisons having no physiotherapy service (see Table 1). However, this statistic produced by Graham [8] was prior to the transfer of prisoner healthcare from the Scottish Prison Service to the NHS.

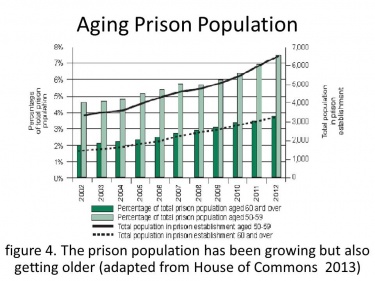

The Scottish Government [9] emphasised that once prisoner healthcare became the responsibility of the NHS, prisoners would receive improved opportunities to benefit from NHS care in keeping with services provided to the local community. With an increasing prison population along with an aging population, more physiotherapists are likely to be required in the prison service.

What to Expect [edit | edit source]

Conditions [edit | edit source]

Musculoskeletal Conditions[edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

Millions of people are affected by musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders worldwide, and MSK injuries are a great burden to the healthcare system. [10]. MSK disorders include a wide range of disorders such as osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, low back pain, muscle/tendon/ligament injuries to name but a few. There is a massive variety in causes of MSK injuries which include sporting activity, trauma, poor postures and physical inactivity. Prisoners may be more exposed to these causes, and as a result, MSK injuries are quite common in prisons. Physical inactivity is prisons is common and greatly contributes to the amount of MSK injuries. Changes in dietary and physical activity patterns are often the result of environmental and societal changes associated with development and lack of supportive policies in sectors such as health, agriculture, transport, urban planning, environment, food processing, distribution, marketing and education. [11]

Causes and Prevalence [edit | edit source]

Physical inactivity

Fischer et al. [12] found that class A drug users had high levels of physical activity prior to incarceration. Their walking activity significantly decreased during their prison term, posing a challenge to maintaining healthy activity levels.

How physical inactivity can cause MSK pain: [13]

- Reduces bone mineral density causing osteoporosis

- Increases risk of obesity which can result in conditions such as osteoporosis

- Muscle weakness can cause joint instability and abnormal movement causing pain

Why prisoners may be more susceptible to MSK pain (*):

- Limited exercise time

- Limited/lack of training equipment

- Lack of OR lack of access to appropriate training guidance

- Uneducated on the benefits of exercise

- Lack of motivation

- High levels of depression/mental health issues in prisons

- Fear of involving with other prisoners

- Prolonged bed rest/poor postures

- Unsupportive beds/chairs

A recent study by Herbert et al, found that male and female prisoners were less likely to participate in adequate physical activity than the general population of similar ages. However despite this fact male prisoners in the UK were less likely to be obese than the general population[14].

Improper use of gym equipment and excessive weightlifting

As mentioned by Physiotherapist D, prisoners can become quite inventive with their workouts in their restricted environment. The following video provides an example of workout regimes in male and female Unites States prisons[15]. Please be advised that the video is quite lengthy, so the following are relevant time markers for physical activity clips:

0:00 --> 05:42: comparison between male and female physical activity in prison

36:03 --> end: Examples of inventive workouts

Another cause for the large complaints of MSK pain in prisons is due to the weightlifting culture in prisons. Many prisoners use their time in prison to “bulk up” and, as a result, lift very heavy weights each day. This also shows them to be more masculine amongst other prisoners. Here, prisoners are the opposite of the physically inactive, and are overactive. By lifting heavy weights each day, they are not giving their muscles sufficient time to recover and become higher risk of developing overuse injuries. Overuse injuries occur when the rate of injury exceeds the rate of healing and adaptation[16]. This results in increased presentation of muscle strains and tendon injuries. A major problem for physiotherapists in prisons is that when they see patients for injuries such as overuse injuries, they are unable to keep the patients out of the gyms. Going to the gym becomes a way of life in the prisons and even with an injury, they continue to lift heavy weights, and do more harm (*).

Another factor which contributes to these injuries is due to the lack of qualified personal trainers to teach and supervise these weight lifters on correct technique, and advise them on resting periods. Improper technique can lead to abnormal movement with a heavy weight causing muscle injury. This poor training technique combined with reduced recovery times results in the development of MSK injuries.

Recreational Injuries(*)

As well as injuries specific to prisoners, physiotherapists commonly have prisoners present with injuries regularly seen in the public. During their recreation time, prisons have the opportunity to play a variety of sports such as soccer, badminton, basketball etc. Therefore, it is no surprise soft tissue injuries and fractures are also quite common. Fights are also more common in a prison environment, and this results in an increased numbers of trauma injuries.

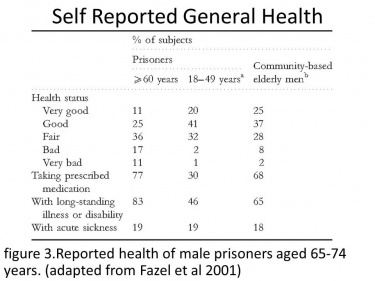

Elderly Prisoners

As our population is ageing, our prison population is also ageing, which adds even more of a healthcare burden on the prisons. Elderly people are more at risk to developing chronic disease than younger people, and it is no surprise that elderly prisoners present with more MSK conditions in comparison to the general public. A study by Fazel et al[17]. showed that there were over 1000 prisoners over the age of 60 in England and Wales, and this number is expected to increase in the future. Out of these 1000 prisoners, 24% had recorded MSK problems, and 43% self-reported MSK problems. These figures show the need for regular physiotherapy in prisons, for MSK conditions alone.

Physiotherapy [edit | edit source]

The major injuries which prisoners present to physiotherapy are (*):

- Low back/neck pain due to heavy weightlifting, poor postures, unsupportive beds/chairs, inactivity

- Fractures due to sports activity or fighting

- Soft tissue injuries such as shoulder or ankle injuries due to weightlifting, sports activities or fighting

- MSK injuries amongst elder prisoners

From above, it is evident that many prisoners lead a sedentary lifestyle, lift heavy weights or participate in sporting activities which may contribute to the high numbers of MSK patients that may be treated in prisons each year. Physiotherapy has been proven to reduce MSK pain, which in turn increased cognitive function, reduces the prevalence of anxiety and depression, and enhances quality of life. [19]. MSK problems can be treated with a variety of techniques including exercise prescription, provision of equipment, education and injection therapy; however, there are barriers to some of these treatment options which need to be considered (see Barriers section).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease [edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

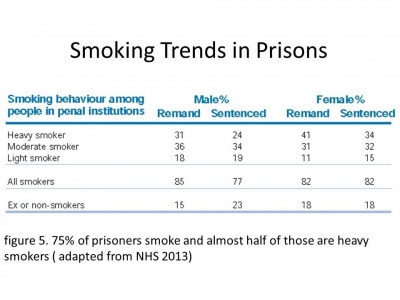

CSP's Frontline magazine highlighted the need for cardioprespiratory physiotherapy in prisons due to the increased number of prisoners that smoke, which is further reinforced by a statistic reported by Conroy stating that it is estimated 90% of prisoners smoke[20]. Furthermore, due to the increasing ageing population, the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in prisons is also likely to increase putting a greater demand on physiotherapists treating respiratory conditions, predominantly COPD. COPD, which is made up of chronic bronchitis and emphysema, is characterised as a difficulty in breathing due to permanent damage to the lungs. COPD may also contribute to other respiratory problems such as obstructive bronchiolitis, pulmonary vascular disease, cor pulmonale (right sided heart failure and pulmonary heart disease), and systemic syndrome of cachexia and muscle weakness. While the damage on the lungs is non-reversible, it is a preventable and treatable condition[21]. It is the most prevalent cause for morbidity and mortality worldwide and, subsequently, places a heavy economic and social burden on governments[22].

Pathophysiology

COPD effects four compartments of the lungs – central airway, peripheral airway, lung parenchyma, and pulmonary vasculature[22]. The common risk factors (listed below) cause an inflammatory response in these areas leading to pathological lesions in COPD sufferers[21]. Additionally, the lungs are susceptible to an imbalance of proteinases and antiproteinases, and oxidative stress, resulting in the following physiological defects:

| Pulmonary Effects | Extrapulmonary Effects |

|

cilliary dysfunction |

muscle weakness and wasting |

| mucous hypersecretion | depression |

| airflow limitation and hyperinflation | cardiovascular disease |

| gas exchange abnomalities | metabolic syndromes (diabetes, obesity, high BP) |

| pulmonary hypertension | endorcine effects |

| systemic effects | anaemia |

| malignancies |

Causes and Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of COPD’s effect on economy is greatly underestimated due to its consequential late diagnosis, because people often present with moderate or severe symptoms. Onset of the disease can occur as early as 35 years old; however, it is more commonly seen in individuals over the age of 65[24]. Several factors, including late diagnosis and socioeconomic factors, are responsible for this varying age in diagnosis. Characterised by a progressive reduction in airflow resulting in an atypical inflammatory lung response to carcinogenic particles or gases, COPD is a preventable and treatable disease state. Smoking is the leading cause of COPD, however other factors, such as air pollution, environmental factors, and genetics factors, can also be precursors to the development of COPD[24].

Smoking - the leading cause of COPD

It has been estimated that smoking contains 1017 reactive oxidant species (ROS). ROS instigate a wide range of inflammatory, mucosecretory, proteolytic, and fibrotic responses, which consequently cause the release of chemotactic factors and cytokines due to epithelial cell injury and macrophage activation. Macrophage and neutrophil involvement cause the breakdown of the extracellular matrix, which corresponds with an inflammatory response. Pathologically, an increase in cigarette smoke parallels a greater number of inflammatory and repair (fibrosis as a consequence) cycles on these response systems, which commonly manifests as mucus hypersecretion, fibrosis, proteolysis, and airway and parenchymal remodelling[21]. Smoking cessation can gradually reduce your risk of getting COPD, or slow its progression if diagnosed in the earlier stages of COPD. Initiatives are being made in efforts to decrease smoking rates in prisons. Most recently, a smoking ban has been proposed for prisons in England and Wales. See 'COPD and Physiotherapy: In the News'.

Physiotherapy

[edit | edit source]

Various physiotherapy techniques have been well-documented in having a positive effect on symptoms experienced by COPD patients. Common techniques include the following:

Manual Chest Techniques[25][26]:

- chest percussion

- chest vibration

- chest shaking

Breathing Exercises[27]:

- diaphragmatic breathing

- breathing control

- pursed lip breathing

Airway Clearance Techniques[27]:

- active cycle of breathing technique (ACBT)

- forced expiration technique (FET)

- autogenic drainage

- positive expiratory pressure (PEP) (incoporating equipment such as the PEP mask, the Flutter, the Cornet, and the Acapella)

- intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB)

The benefits of physical activity also cannot be underestimated. Pulmonary rehabilitation classes are commonly offered in the community. The goal of pulmonary rehabilitation is to assist the clearacne of secretions and improve overall quality of llife. Patients suffering from COPD in prisons would greatly benefit from these types of programmes; however, there are many challenges associated with organising these programmes, including funding, security, and manpower.

In the news: COPD and Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Recent publications by the CSP's Frontline magazine presented initiatives being made by UK physiotherapists working in English and Welsh prisons to improve the health of prisoners suffering from COPD. It was estimated that patients needing to be transferred and escorted to hospital was costing £500 per incident [1]. The article raised awareness of the high prevalence of COPD in prisons and, particularly, the lack of training and/or equipment that is available to provide rehabilitation to prisoners suffering from COPD. In Maidstone prison in England, a pulmonary rehabilitation physiotherapist and a prison healthcare nurse organised and led a two-hour health promotion and exercise class two times per week over a seven weeks. The classes consisted of an educational component (one hour) from a member of the multi-disciplinary team (e.g. GP, dietician, physio, nurse, pharmacy assistant) discussing smoking cessation, mental health, benefits of exercise, and breathing techniques to name a few. Following these classes, patients reported feeling less out of breath, had better recovery times post exercise, decreased heart rate and blood pressure, increase in energy, positive mental state, increased motivation, and a feeling of improved general wellbeing.

Another initiative being proposed by the Prison Service is instilling a smoking ban (similar to the smoking ban in public places) that would restrict smoking inside and outside prison premises. The primary aim of this ban is to reduce the amount of second-hand smoke incurred by prison staff and non-smoking prisoners. Secondly, it would help reduce the amount of COPD cases suffered by prisoners, and alleviate stress on clinicians and finances. Initially proposed in 2007 by the Prison Officers Association (POA), the smoking ban has been also supported by the Association for Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care[28]. However, the success of a smoking ban would need to be supported by an established programme such as the seven-week health promotion and exercise class offered in Maidstone Prison. Other countries who have also recently adopted smoking bans in prisons include New Zealand, the United States, and Canada.

A commentary written by Butler et al[29]. discussed the need for smoking bans in prisons, the realities of implemention, and the difference between banning and quitting smoking in Australian prisons. Australian prison data showed that a large majority of prisoners continued to smoke in spite of a smoking ban, and an even greater percentage smoked after their release. Many professionals and health care providers are also aware of the possibility of the smoking ban creating another 'black market'; hence, commonly associated problems include standovers, intimidation between prisoners or gangs, smuggling, trading sex for tobacco, and the requirement for additional policing of another banned substance. While initial intents of instilling a smoking ban are beneficial to everyone's health in prison, legislative efforts might be better placed in introducing smoking education and cessation programmes. A survey conducted in Australian prisons between 1996-2001 indicated that nearly half of all prisoners would have liked help to quit smoking, while only 6% of prisoners received help in 2001. Furthermore, a smoking cessation trial was conducted in a correctional centre in Australia involving combined nicotine replacement therapy, pharmacotherapy, and CBT with results indicating a 40% rate of cessation at five months.

The following BBC News video clip provides a brief summary of the UK smoking ban:

In regards to physiotherapy treatment of COPD, the benefits for patients are short and long term. Improved exercise capacity, increased quality of life, increased independence, improved sense of control over their condition, emotional stability, and decreased breathlessness and fatigue are just a few of the many benefits of rehabilitation[27]. While prisoners are often incarcerated for wrong doing, this should not equate to a subsequent decline in their physical and mental state, in addition to compromising the well-being of those who surround them, including fellow non-smoking prisoners and prison staff. Furthermore, if prisoners are instilled with a sense of self efficacy and control over their COPD, the repercussions on society and health care following their release from prison could be greatly minimised.

Mental Health in Prison [edit | edit source]

Mental illness has a higher prevalence in the prisoner population. 72% of males and 70% of female (sentenced) prisoners have 2 or more mental health disorders[31]. 9 out of 10 met the office of national statistics criteria for having at least one mental illness[32]. Drug Prescription data supports this, showing that mental health related medication is the highest dispensed in prison[31].For example, 40% of men and 63% of females have neurotic disorders, a level three times that of the general population[33]. Neurotic disorders, such as borderline personality disorder, include behaviours such as anxiety, anger, loss of contact from reality, difficulty maintaining stable and close relationships, and threat to others. This will affect the physical health of the individual and their relationship with their healthcare worker[34]. Therefore, mental illness presents a challenge to treatment and may also pose challenges for healthcare workers during treatment in prisons [33].

There are several ethical issued faced by prison healthcare workers in relation to mental health.

Consent[edit | edit source]

As previously mentioned, due to the high incidence of mental health illness' in prisons physiotherapists need to be aware of the Mental Health Act (1983). A patient must give consent to proceed with a treatment or test for the healthcare worker to be legally allowed to continue. If consent is not given and healthcare worker continues, it can be deemed assault. When a patient’s mental illness is leading to behaviour which is an immediate danger to self or others, they are analysed as not having capacity and can be treated under the Mental Health Act (1983). They must, however, be transferred out of the prison and into an NHS or qualified mental health unit to be treated. At all other times, a patient must give consent[35].

Environment [edit | edit source]

The prison environment itself can have detrimental effects on a prisoner’s mental health due to the lack of decision making, minimal family and friends contact, and decreased activity. These can all lead to the development of depression, anxiety and other mental health concerns[35]. Any concerns regarding mental health should be referred immediately and the patient should be assessed within 24hrs[36].

Isolation [edit | edit source]

Patients can be put into isolation as a punishment or reward. Isolation can have detrimental effect on a patient’s mental health, and healthcare workers dealing with a patient who has been in isolation must be aware of this and immediately raise any concerns [35][36].

Prison Staff vs. Health Staff[edit | edit source]

The priorities of prison staff and healthcare staff differ. This may become an issue when a patient requires treatment. If prison staff are thin on the ground, movement of prisoners through the prison becomes a concern, and staff may pressure health care staff to go to the prisoner[35].

Physiotherapists working in the prison setting should be aware of policies and procedures regarding mental health in relation to treatment. Standards of care must always be met; however, staff should ensure safety of themselves and others[35].

Barriers to Treatment in Prison [edit | edit source]

Equipment (*) [edit | edit source]

Working as a physiotherapist in a prison is quite different to that of a normal outpatient clinic in a number of ways. After speaking to four physiotherapists who have had experience in treating patients in a prison setting, three mentioned being very limited in available equipment.

Physiotherapist A is involved in prison healthcare throughout the community. In an email conversation on 18 October 2013, physiotherapist A mentioned that in the prison that she works at, she has no access to gym equipment or rehab input at the gym. She finds that the general lack of equipment and resources is a barrier to treatment in prison.

Physiotherapist B runs a MSK clinic once a week in a local prison. In an interview conducted on November 8 2013, physiotherapist B found that a lack of equipment posed quite a challenge for her. She reported that she worked in a small room with a plinth and could not have any other physiotherapy equipment on display. Items such as staplers, biros and tendon hammers must be kept out of reach of the patients as these are all potential weapons that could pose a threat to her or the patient themselves. If a patient requires a steroid injection, this must all be prepared prior to their treatment and kept in a cupboard until it is needed. The trolley and sharps box must be kept nowhere near the patient as she was forewarned that prisoners would reach inside the sharps bucket to obtain a needle for personal use. Again, posing a serious threat to herself, the patient and their fellow prisoners.

Other practicalities that we take for granted in a normal clinical setting include the availability of walking aids. Physiotherapist B spoke about the process of providing a prisoner with a walking aid as quite time consuming. As she is not allowed to keep any walking aids in the treatment room, if a patient does require one she has to contact a prison officer to supervise the patient while she goes to get the walking aid which are stored upstairs.

Physiotherapist B also spoke about not being allowed to provide patients with therabands for rehabilitation purposes as again, they could cause significant harm against themselves and/or other prisoners. This means that you have to constantly improvise, or as physiotherapist B's stated “make the most of health care in a situational confinement”. For example, she advises patients to lift empty lemonade bottles when doing pain-free exercises for rotator cuff injuries instead of using a theraband. This can potentially impair rehab, for example, if a patient has carpal tunnel syndrome the metal plates must be taken out of the splint which can reduce the support provided. Another example is if a patient requires a TENS machine or a knee support, she must provide the patient with a permission slip that will allow a friend/relative to buy it for them externally and bring it into the prison.

In the same interview, physiotherapist B mentioned that the prisoners had access to a state of the art gym; however, due to the competitive nature of the prisoners, this often results in more injuries due to excessive weight lifting. A cardiovascular room is also available for patients to do their rehab in but only has a small number of machines.

Physiotherapist C visits one patient in prison and again she finds that attempting to rehab a patient in prison is certainly more challenging than a normal outpatient setting. This was evident in an phone conversation on 15 November with physiotherapist C when she spoke about the small space she has to work in, making it difficult to practice transfers with patients. She is not allowed to give out therabands to patients and finds that compliance is also an issue during rehab.

In contrast, physiotherapist D did not encounter the same issues with equipment as the previous three physios. In the prison health centre she had a plinth, a bike, a trampet and hand weights. She reported no problems with issuing therabands or walking aids to patients as long as she checked with prison officers. Walking aids will be checked thoroughly as it has been common to find drugs stashes in elbow crutches. Similar to physiotherapist B, she also mentioned that the metal plates had to be taken out of wrist splints which may have had a negative impact on treatment as she saw a lot of wrist and hand injuries. If a patient required a TENS machine, a certain type was provided that did not have four bolt batteries as prisoners could use this to their advantage. Her main issue was not so much equipment but more so restrictions about the actual prison environment. Prisoners could be in their cell for up to 8 hours on a weekend day so it was important for her to try and create exercises for them to do in their cell environment. In the prison that she worked in, every prisoner had access to a well-equipped gym however this was behaviour dependant.

As physiotherapists, we must always be able to improvise and adapt our treatment as appropriate. This is definitely the case in the prison setting where creativity and ingenuity is needed to think up of effective exercises with limited equipment ensuring that the best care is provided for the patient.

Security (*) [edit | edit source]

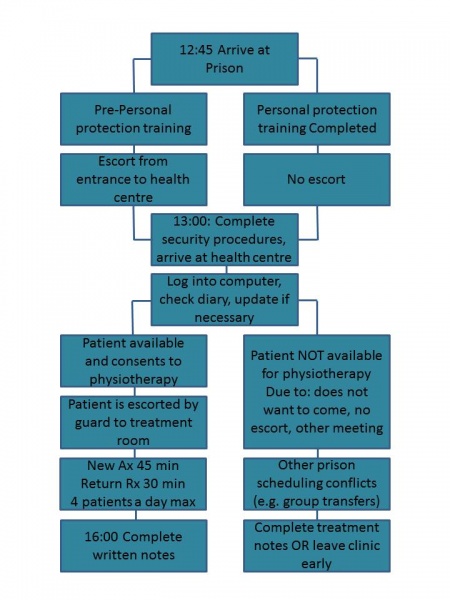

Security is obviously a major concern in prisons and remains a priority when treating prisoners both for the safety of the health professionals and the prisoners. Based on the information obtained from the conducted interviews, there are definite security considerations which must be taken into account when working with prisoners.

Physiotherapist A also mentioned the presence of sniffer dogs on occasions and described it as going through security at an airport.

Once inside the prison, you are free to walk to the health centre and around the prison by yourself, but only if you have completed the intense personal protective training program. For physiotherapists who have not completed such training, they must be accompanied by a security guard at all times. Each health professional wears a small personal alarm at all times, which can be pressed in case of an emergency.

While treating patients, the physiotherapist must continue to be aware of their own security. Physiotherapist B mentioned that she is not usually accompanied by a security guard during treatment, and there was generally only one security guard in the health centre. High risk patients are labelled “no lone working”, and are usually accompanied by another health professional. She also discussed in her interview how she never allows the prisoner to come between herself and an exit door in case she needs to make a quick exit for any reason. She also highlighted how important it was not to leave any equipment lying around, which the prisoner could use as a weapon; even items such as stationary.

Physiotherapist C only saw one prisoner each week, but in order to improve the patient’s functional ability, she had to see the prisoner in their cell. As she has not completed her intense personal protective training, she is always accompanied by a security guard. She brings an assistant with her into the cell, and the security guard stands at the door in case he is needed.

While security is of extreme importance in prisons, physiotherapist B described how it adds considerable time constraints to her working day. To see a patient, she must inform a security guard who would accompany the prisoner from their cell to the treatment room. The prisoner is not informed prior to this when they will be seen for physiotherapy. Some prisoners may refuse treatment at the time or may not be in their cell and it takes time for the security guard to return to the health centre and to get a different prisoner for treatment. This results in delays in prisoners being brought for treatment and is very frustrating for the physiotherapist. She believes that a lot of time is wasted while she is waiting for patients, and that a different system needs to be adapted in order to counteract this.

All physiotherapists whom we have interviewed have expressed anxious feelings when beginning work in the prisons. They all discussed nerves going through security proceedings for the first time, and feelings of anxiety when treating prisoners at the beginning. However, following a few weeks of working there, the feelings gradually subsided. One physiotherapist did, however, express feelings of anxiety when passing prisoners in the hallways, but said having a security guard and alarm bell with you helps to ease this.

Occurrence of Incidence in Scottish Prisons[edit | edit source]

- In a 4 year period (Jan 2009 to Dec 2012) 20 staff members took time off work as a direct consequence of an assault; the time taken off ranged from below 5 days and up to 90 days[37].

In 2012[38]:

- 21 prisonser were reprimanded for recklessly endangering the health and safety of others

- 31 were punished for intentionally endangering the helath or safety of others

- 8 prisoner were punished for being disrespectful to any person other than a prisoner who is at the prison

- 3 prisoners were punished for trying to start a fire

- 4 people commited an indecent or obscene act

- 92 were punished for commiting an assault

Training (*)[edit | edit source]

Mandatory

- Prison Induction

- Annual Personal Protection Training (all physiotherapists in NHS have to do this) but more intense if working in prisons. Half a day training, including videos and practicals.

- Advice from Healthcare Manager: one physiotherapist noted that this was the first form of 'training information' given. Example from physiotherapist B: “remember to keep between the door and prisoner so exits are not blocked”

Optional/Desirable

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

- Tutorials or training in the psychology of manipulative behaviour

- Tutorials or training in the psychology of prisoners

- Suicide training

- Recommended that applying physiotherapists have at least 5 years physiotherapy work experience due to complexity of issues faced in prison

It is important to note that all training is taken out of clinic time.

Politics[edit | edit source]

In England and Wales, the NHS funded through taxation provides health service at the local level through 300 primary care trusts, each serving an approximate population of 250,000. Around 85 of these primary care trusts are responsible for the provision of healthcare in one or more prisons. In April 2006, the NHS commissioned all health services for prisoners in publicly funded prisons throughout England and Wales similar to the way that it provides services for all British citizens[39].

In Scotland, the responsibility of prison healthcare was that of the Scottish Prison Service up until 2011. A decision was made by ministers in 2008 to transfer the responsibility of prisoner healthcare to the NHS. The transfer intended to ensure equity in health care so that prisoners would receive their care from NHS as does the general population and also to ensure that both European and International standards for prisoner health care were maintained[40]. On 1 November 2011, in accordance with Health Board Provision of Health Care in prisons (Scotland) Direction 2011, prisoner health care became the responsibility of the Health Board as oppose to the prison service[41].

Upon this agreement being reached in 2011, both parties had a number of responsibilities to uphold in order to ensure that prisoner healthcare was meeting the EU and International standards. The main responsibilities of the NHS as outlined in the Memorandum of Understanding compiled by Scottish Government are as follows[41]:

- The management, training and support of directly employed health care staff, including support functions

- Ensuring that staff teams have an appropriate skill mix of professional staff, assistants and administrative staff

- Maintenance and replacement of all clinical fixed and non-fixed assets within health care premises

- Training and development of staff for clinical and supporting purposes

- Clinical performance management and monitoring, and prison liaison

The Scottish Prison Service and individual prisons also undertook a number of responsibilities such as:

- Environments within prisons that protect and promote health and good hygiene

- Security and good order within health centres

- General care and support of prisoners with health problems, including collaboration with care planning and delivery

- Escorting functions for security purposes, both within and outwith the establishment

- Facilities management and cleaning services within the health centre

- Training of clinical staff for purposes of working effectively and safely within the prison setting

- Effective liaison with Health Boards and Scottish Government

Despite this agreement coming into play over two years ago, it is still evolving. Physiotherapist A mentioned that “because the transfer of prisoner healthcare to the NHS, the service is still developing and gaps in the service are being looked at”.

For example, the prison healthcare standards state that the provision of health care facilities will allow for a safe and effective delivery of healthcare with a designated area (minimum 16m²) available to conduct an initial health interview on entry to prison with conditions of privacy and confidentiality[8]. However, the issue of an ageing population was highlighted by physiotherapist A who has experience of working in a prison as she acknowledges that there will be a significant amount of elderly patients in prison in the future and the cell environment is not the most appropriate for some of their disabilities and additional requirements.

Cost[edit | edit source]

Along with ensuring high standards of healthcare, the transfer of prison healthcare to the NHS may also be cost effective. A report of the prison healthcare advisory board (2007) reviewed the costs of prisoner healthcare[42]. At the time the report was published, when the Scottish Prison Service had the responsibility for prisoner healthcare, the estimated current revenue investment in prison health services in Scotland was £16m. They emphasised that the need for healthcare in this small population was greater than both supply and demand (in that expressed need in a relatively disempowered population with multiple layers of health problem is incompletely expressed). £16m for this enhanced primary care service equates to over £2,100 per prisoner place per year. This figure is much greater than the average spend on every patient in NHS Scotland for all services. Upon transfer of responsibility to the NHS, cost saving measures could be made such as: "general practitioner services where the present agency arrangement would be replaced, avoiding potentially an element of premium cost. The buying power of the NHS through its National Procurement initiative is likely to derive cost benefits on purchasing prescription drugs and medical supplies”[42].

Focus Prisoner Education (2009) argue the point that although prisoners are entitled to NHS care as with any other British citizen, the facilities within the prison system are sometimes inadequate[43]. This is simply because each prison cannot have its own hospital and can, therefore, lack necessary equipment. The result is that prisoners often have to be moved from one prison to another, or to an outside hospital, for treatment. This not only costs yet more money in direct expenses (administration, transport, guarding a prisoner while at a general hospital and so on) but can lead to delays in treatment. NHS (2006) mention that under original manual system, sick inmates requiring medical attention were taken to be assessed at hospital under a police escort incurring a charge of approx £2,500 per return visit[44]. This cost entailed escort and bed duties only.

There is limited evidence on the cost effectiveness of NHS run prisoner healthcare; however, a financial review of prisoner healthcare was carried out recently by Scottish Government Finance Department[45]. The suggestion of the development of a formula for a cost per prisoner and this will be considered by the department of finance once the report has been signed off.

NHS Scotland financial summary for 2011/2012 found that the NHS had a £10 million underspend of their £10,537 million budget. The report acknowledged that this was achieved despite managing the additional costs associated with increased activity in General Dental Services and General Ophthalmic Services and the transfer of responsibility for Prisoner Healthcare from the Scottish Prison Service[46].

Day to Day[edit | edit source]

Related Publications[edit | edit source]

Other articles on the smoking ban:

UK: http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/older-prisoners-may-be-missing-out-physiotherapy-assessments

UK: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-24172061

UK: Action of Smoking and Health International Overview http://ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_740.pdf

Australia: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-11-03/qld-prison-smoking-ban/5066404

New Zealand: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10432294

Training:

NHS. Cognitive behavioural therapy. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Cognitive-behavioural-therapy/Pages/Introduction.aspx

CHOOSE LIFE. Training. Available from: http://www.chooselife.net/Training/index.aspx

Guarding against Manipulation. http://www.bfcsa.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/223759/Guarding-against-Manipulation-by-Criminal-Offenders.pdf

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mcmillan, I.A. No bar to treatment 2013. http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/no-bar-treatment (accessed 18 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ministry of Justice. Story of the prison population: 1993-2012. England and Wales. 31 p. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/218185/story-prison-population.pdf (accessed 21 November 2013).

- ↑ Health and Care Professions Council. Standards of Proficiency: Physiotherapists. http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10000DBCStandards_of_Proficiency_Physiotherapists.pdf (accessed 21 November 2013).

- ↑ Prison Healthcare Service 2012 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TysJFj4ofTU (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ The Scottish Prison Service 2013 Frequently asked questions. http://www.sps.gov.uk/faq.aspx#FAQno18 (accessed 10 October 2013).

- ↑ BBC NEWS. Scotland politics 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-18645888 (accessed 9 October 2013).

- ↑ Berman G, Dar, A. Prison population statistics. UK Parliament. 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Graham L. Prison health in Scotland: A healthcare needs assessment. Scottish Prison Service 2007.

- ↑ Scottish Government. Directorate for health and social care integration; primary care. http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/pca/PCA2011(M)15.pdf (accessed 5 November 2013).

- ↑ Woolf A, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 2003; 81 (suppl 9):646-656.

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Obesity and Overweight. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html (accessed 5 November 2013).

- ↑ Fischer J, Butt C, Dawes H, Foster C, Neale J, Plugge E, Wheeler C, Wright N. Fitness levels and physical activity among class A drug users entering prison. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2012; 46(suppl 16):1142-1144.

- ↑ Warburton D, Nicol C, Bredin S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006; 174(suppl 6):801-809

- ↑ Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, Doll H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. The Lancet 2012; 379 (suppl 9830):1975-1982

- ↑ Prison Life: Workout Tattoos and Food In Prisons, 2013.

- ↑ Brotzman S, Manske R. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby: 2011.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Fazel S, Hope T, O’Donnell I, Piper M, Jacoby R. Health of elderly male prisoners: worse than the general population, worse than younger prisoners. Age and Ageing 2001; 30(suppl 5):403-407.

- ↑ House of Commons. Older Prisoners. London: The stationary office limited; 2013 Jul. 144 p. Report No.: 5 p.

- ↑ Fox, K. The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public health nutrition 1999; 2 (suppl 3a);411-418.

- ↑ Conroy, B.D. The Management of COPD in a Secure Prison Environment. 2013. Available from: http://priory.com/cmol/copdprison.htm (accessed: 20th November, 2013).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Hansel, T.T. & Kon, O.M. (2009). Chapter 1: Global Burden and natural history of COPD, IN Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Oxford University Press, Oxford: UK, http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7xyiBAtcnTMC&lpg=PT95&ots=Srs1JIvE5r&dq=kon%20and%20hansel%20copd%20online&pg=PT95#v=onepage&q=kon%20and%20hansel%20copd%20online&f=false (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Celli, B.R., MacNee, W. & committee members. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004; 23: 932-946.

- ↑ NHS. Smoking and health inequalities. Health development agency, 6 p.;http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/documents/smoking_and_health_inequalities.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 British Lung Foundation: COPD. http://www.blf.org.uk/Conditions/Detail/COPD (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Garrod, R., Lasserson, T. Role of physiotherapy in the management of chronic lung disease: An overview of systemic reviews. Respiratory Medicine. 2007; 101: 2429-2436.

- ↑ Yohannes, A.M., Connolly, M.J. A national survey: percussion, vibration, shaking and active cycle of breathing techniques used in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiotherapy. 2007; 93: 110-113.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Mikelsons, C. The role of physiotherapy in the management of COPD. Respiratory Medicine: COPD Update. 2008; 4: 2-7.

- ↑ Mcmillan, I.A. Plan to stub out smoking in prisons given cautious welcome by physios. 2013. http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/plan-stub-out-smoking-prisons-given-cautious-welcome-physios (accessed 18 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Butler, T., Richmond, R., Belcher, J., Wilhelm, K., Wodak, A. Should smoking be banned in prisons? Tobacco Control. 2007; 16: 291-293.

- ↑ BBC News – Smoking in prisons could be banned by 2015.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Graham L. Prison Health in Scotland: A Healthcare Needs Assessment. Scottish Prison Service 2007. http://www.sps.gov.uk/Publications/Publication85.aspx(accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Royal College of Psychiatrists. Prison psychiatry: adult prisons in England and Wales. Royal College of Psychiatrists 2007. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/cr141.pdf(accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Prison Reform Trust. Mental Healthcare in Prisons. http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/ProjectsResearch/Mentalhealth. (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ NHS Choices. Borderline Personality Disorder. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/borderline-personality-disorder/Pages/introduction.aspx (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Mental Health Primary Care. Ethical Issues. http://www.prisonmentalhealth.org/page_view.asp?c=17&fc=012&did=272. (accessed 22 Nov 2013)

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Graham L. Audit of the implementation of the mental health (care and treatment) (scotland) act 2003 in the Scottish Prison Service. Scottish Prison Service, 2006. http://www.sps.gov.uk/Publications/Publication87.aspx(accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Scottish Prison Service. Details of staff absences and injuries during 2009-2012. Scottish Prison Service http://www.sps.gov.uk/FOI/FOI-4482.aspx (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Scottish Prison Service. Prisoners' breaches of discipline, 2010-2013. Scottish Prison Service 2013 http://www.sps.gov.uk/FOI/FOI-4603.aspx (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Spurr M. Background on England and Welsh prison system HM Prison service http://www.internationalpenalandpenitentiaryfoundation.org/Site/documents/Stavern/16_Stavern_Report%20England%20and%20Wales.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2013).

- ↑ The Scottish Prison Service. Frequently asked questions. http://www.sps.gov.uk/faq.aspx#FAQno18 (accessed 10 October 2013).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Scottish Government. Directorate for health and social care integration; primary care. http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/pca/PCA2011(M)15.pdf (accessed 5 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Scottish Government. Prison healthcare advisory board: potential transfer of enhanced primary healthcare services to the NHS. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/924/0063021.pdf (accessed 6 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Focus Prison Education. The cost of prisons. http://www.fpe.org.uk/the-cost-of-prisons/ (accessed 10 October 2013).

- ↑ NHS. Telemedicine in prisons. digital.innovation.nhs.uk/dl/cv_content/6659 (accessed 6 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Miller J. Prisoner Healthcare in the NHS in Scotland- 1 year on. The Scottish Parliament. 2013.

- ↑ Scottish Government. NHS Scotland chief executive's annual report 2011/2012. The Scottish Government. 2013.