Alzheimer's Disease

Original Editors - Students from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project. Top Contributors - Josie Little, Stephanie Schwebler, Laura Ritchie, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Hayaa Yousri, Emily Pollom, Dave Pariser, Vidya Acharya, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Lauren Lopez, 127.0.0.1, Shaimaa Eldib, Joseph Ayotunde Aderonmu, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Tolulope Adeniji, Safiya Naz, Wendy Walker and Naomi O'Reilly

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Dementia is a general term for memory loss and other cognitive abilities that are required for activities of daily living [1]. Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia worldwide[2].The primary known risk factor for the disease is ageing, but AD is not a normal part of ageing. Alzheimer’s Disease is progressive so symptoms will worsen with time. There is currently no cure for the disease, but treatments are available to slow down the progression[3]. There is a complex intertwining of mechanisms that manifest as AD. The understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition is constantly changing [4].

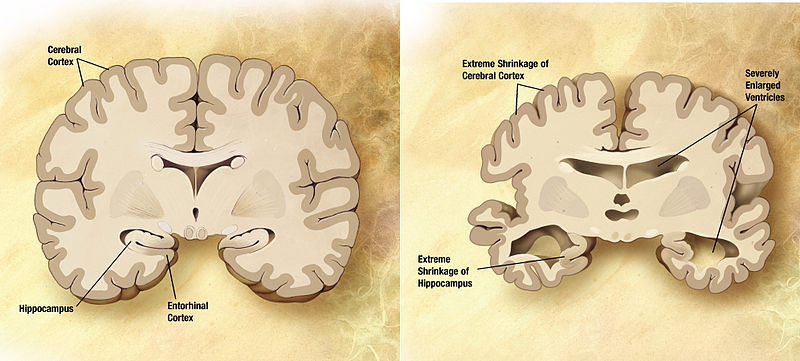

Alzheimer's Disease is characterised by cortical atrophy and a loss of neurons, particularly in the parietal and temporal lobes. Also with loss of brain mass there is an enlargement of the ventricals of the brain[5]. The changes in the brain tissue slowly cause cognitive changes in the person.

Senile plaques which consist of extracellular amyloid are found in high concentrations in patients with Alzheimer's when compared with normal ageing brains [6]. Neurofibrillary tangles in the neocortex, amygdala, hippocampus and nucleus basalis of Meynert can also occur[7]. In a normal functioning brain, B-amyloid dissolves and the brain reabsorbs it. When it is not reabsorbed, the B-amyloid protein can fold in on itself. The proteins then connect with one another and form a plaque. These plaques cause an inflammatory response that results in the damage of more neural tissue[8][9]. There may be involvement of the thalamus, dorsal tegmentum, locus ceruleus, paramedian reticular area and the lateral hypothalamic nuclei[7].

Degenerative changes in these areas are caused by: decreased activity of choline acetyl transferase in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus and a loss of cholinergic neurons in the cholinergic projection pathway to the hippocampus[7].

This link will guide you through a tour of the brain and explain further how Alzheimer's affects the brain.

Alzheimer's Disease Brain Tour

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

As of 2017, approximately 5.5 million peop[10]le have Alzheimer's Disease in the United States and about 8 million are affected around the world[11]. It is expected that by 2050 that number will have increased almost three fold to around 115.4 million. The known prevalence is 6% in people over the age of 65, 20% in people over the age of 80, and more than 95% in those 95 years of age.Alzheimer's disease is the sixth leading cause of death in adults[12]. The period from onset to death is usually seven to 11 years.

While death from other top 10 diseases have been observed to decline, from 2000-2014 Alzheimer’s disease as the primary cause of death has increased by 89%. A retrospective cohort study[13] found cardiovascular diseases (CVD) as a significant cause of death in older people who have dementia with a relatively shorter survival approximately 4 years after the diagnosis of dementia.

Early onset AD manifests between the ages of 30 and 60 years. This occurs in 1-6%of all cases[10]. Late onset AD manifests after the age of 60 years and accounts for around 90% of cases. Two thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women[10]. Older African Americans and Hispanics have an increased likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s or dementia than older white adults [10].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

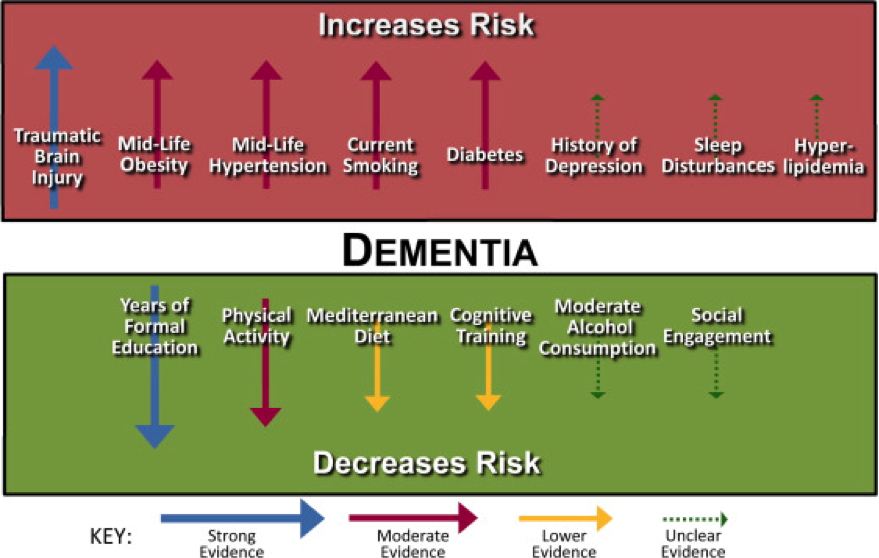

The progression of Alzheimer's Disease is continuous and generally does not fluctuate or improve. Often times the early symptoms can be missed or overlooked because they can be misinterpreted as signs of the natural ageing process[14]. There are some key risk factors that need to be considered with Alzheimer's Disease.

Primary Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Advancing age, >85 y/o risk increases nearly 50%[15]

- Direct family member with the disease (mother, father, brother or sister) Risk genes that increase the likelihood of developing the disease

- Apolipoprotein E-e4 (APOE4) carries the strongest risk of developing Alzheimer’s Disease, this is a genetic mutation of APOE [16]

- Risk believed to increase if carriers of the gene also have a traumatic brain injury

- Deterministic genes have a direct cause of early onset AD, however they only account for less than 5% of cases: amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PS-1), presenilin (PS-2) [17]

- Trisomy 21

- Cardiovascular risk factors: mid-life obesity, mid-life hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus[18]

Possible Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Head trauma - older adults with moderate traumatic brain injury (TBI) risk increases by 2.3x, severe TBI increases risk of AD by 4.3x. Believes to increase risk by increasing beta-amyloid and tau proteins. e.g. falls, MVA, sports injuries [19]

- History of depression

- Progression of Parkinson-like signs in older adults

- Hyperhomocysteinemia

- Folate deficiency

- Hyperinsulinemia[20]

- Lower educational attainment

- Sleep disturbances

- High blood pressure in midlife

- Hyper/hypothyroidism [21]

[22]

There are also some factors that can help to defend a person against developing Alzheimer's disease.

The Possible Protective Factors[23][edit | edit source]

- Apolipoprotein E2 gene

- Regular fish consumption

- Regular consumption of omega - 3 fatty acids

- Years of higher education

- Regular exercise due to cardiovascular benefits increasing oxygen & blood to the brain

- Diets low in sugar and saturated fats

- Prevention of head trauma & falls

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy

- Moderate Alcohol intake

- Adequate intake of vitamins C,E, B6, and B12, and folate.

10 Warning Signs of Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease[24][edit | edit source]

1. Memory changes that disrupt daily life.

- One of the most common signs of Alzheimer’s

- Forgetting recently learned information

- Important dates or events

- Repeating questions or information

- Relying on memory aides or family members

- Typical forgetfulness: Sometimes forgetting names or appointments, but remembering them later.

2. Challenges in planning or solving problems.

- Changes in ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers; e.g. following a familiar recipe or keeping track of bills

- Difficulty concentrating on activities or taking longer to perform

- Typical troubles with planning: Making occasional errors when balancing a check book.

3. Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work or at leisure.

- Difficulty completing daily tasks

- Trouble driving to a familiar place

- Managing a budget

- Remembering rules to a favourite game

- Typical troubles: Occasionally needing help to use the settings on a microwave or to record a television show.

4. Confusion with time or place.

- Losing track of dates, seasons or passage of time

- Trouble understanding something happening immediately

- May forget how they got somewhere

- Typical troubles: Becoming confused about the day of the week, but figuring it out later.

5. Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships.

- Reading

- Judging distances

- Determining color or contrast

- Perception changes: such as passing a mirror and not recognising self

- Typical: vision changes related to cataracts What's typical? Vision changes related to cataracts.

6. New problems with words in speaking or writing.

- Trouble following or joining a conversation

- May stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or may repeat themselves

- May struggle with vocabulary or have trouble finding the right word or (e.g. calling a “watch” a “hand-clock” with Alzheimer's may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have problems finding the right word or call things by the wrong name (e.g., calling a "watch" a "hand-clock"). What's typical? Sometimes having trouble finding the right word.

7. Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps.

- Things may be placed in unusual places

- May lose things and be unable to retrace steps to find them again

- May accuse others of stealing

- These behaviours may increase in frequency over time

- Typical: Misplacing things from time to time like a pair of glasses or the remote.

8. Decreased or poor judgment.

- Changes in judgement or decision-making

- Poor judgement with money or may give large amounts to telemarketers

- May pay less attention to grooming or hygiene

- Typical: making an occasional bad decision

9. Withdrawal from work or social activities.

- Removing themselves from hobbies, social activities, work projects or sports

- Trouble keeping up with a favourite sports team or remembering how to complete a favourite hobby.

- May avoid being social activities

- Typical: Sometimes feeling weary of work, family and social obligations.

10. Changes in mood and personality.

- Suspicious

- Depressed

- Fearful or anxious

- Upset at home, work, with friends or in areas out of comfort zone

- Typical: developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted

Stages of Alzheimer's Disease[25][26][edit | edit source]

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease (Early Stage)[edit | edit source]

- May Function Independently: may drive, work or may be apart of social activities

- Memory Lapses: familiar words, location of objects, names of new people, recently read material

- Difficulties noticed by family, friends and doctors: challenges performing activities at home or work, difficulty planning

- Lack of spontaneity

- Subtle personality changes

- Disorientation to time and date

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease (Middle Stage) [edit | edit source]

- Longest stage, may last for years

- Personality changes: moody or withdrawn, suspicious, delusions, compulsive, repetitive behaviour

- Increased memory loss: forgetfulness regarding personal history, unable to recall address, phone number, or high school they graduated from

- Decreased independence: trouble controlling bowel and bladder, increased risk of wandering or becoming lost, dependence with choosing appropriate clothes for event or season, increased Confusion

- Impaired cognition and abstract thinking

- Restlessness and agitation

- Wandering, "sundown syndrome"

- Inability to carry out activities of daily living

- Impaired judgement

- Inappropriate social behaviour

- Lack of insight, abstract thinking

- Repetitive behaviour

- Voracious appetite

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease (Late Stage)[edit | edit source]

- Decreased response to the environment: decreased ability to communicate and may speak in small phrases, decreased awareness of experiences & surroundings

- Dependence on caregiver: decreased physical functioning: walking, sitting & swallowing; increased vulnerability to infections, incontinence

- Emaciation, indifference to food

- Inability to communicate

- Urinary and faecal incontinence

- Seizures

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

A high level of comorbidity is associated with poor self care, decreased mobility and incontinence. Increased co-morbidity is associated with lower cognitive score observed through a mini-mental status examination.[27]

- Vascular Disease

- Thyroid Disease

- Sleep Apnoea

- Osteoporosis

- GlaucomaCancer

- Rheumatoid Arthritis & NSAIDs

- Depression

Medications[edit | edit source]

Below is a list of some commonly used medications use in the treatments of the symptoms of Alzheimer's. There is also the use of other treatments such as antioxidants, anti-inflammatory agents, and estrogen replacement therapy in women to prevent or delay the onset of the disease.[28][29]

- Donepezil - (Aricept) has only modest benefits, but it does help slow loss of function and reduce caregiver burden. It works equally in patients with and without apoipoprotein E4. It may even have some advantage for patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's Disease.

- Rivastigmine - (Exelon) targets two enzymes (the major one, acetylcholinesterase, and butyrylcholinesterase). This agent may be particularly beneficial for patients with rapidly progressing disease. This drug has slowed or slightly improved disease status even in patients with advanced disease. (Rivastigmine may cause significantly more side effects than donepezil, including nausea, vomiting, and headache.

- Galantamine - (Reminyl) Galantamine not only protects the cholinergic system but also acts on nicotine receptors, which are also depleted in Alzheimer's Disease. It improves daily living, behavior, and mental functioning, including in patients with mild to advanced-moderate Alzheimer's Disease and those with a mix of Alzheimer's and vascular dementia. Some studies have suggested that the effects of galantamine may persist for a year or longer and even strengthen over time.

- Tacrine - (Cognex) has only modest benefits and has no benefits for patients who carry the apolipoprotein E4 gene. In high dosages, it can also injure the liver. In general, newer cholinergic-protective drugs that do not pose as great a risk for the liver are now used for Alzheimer's.

- Memantine - (Namenda) targeted at the N-methyl-dasparate receptor, is used for moderate to severe Alzheimer's.

- Selegiline - (Eldepryl) is used for treatment of Parkinson's, and it appears to increase the time before advancement to the next stage of disability.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values [30][edit | edit source]

Currently, diagnosis of Alzheimer’s relies primarily on signs and symptoms of mental decline. Primary care physicians and physical therapists can screen for dementia presentations, the next section describes tools for recognising dementia or alzheimer’s presentations in patients. Below are current research developments utilised to exclude other possible diagnosis, while confirming the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Onset of the disease occurs between 40 and 90 years old and most often after 65 years old.

Biomarkers[edit | edit source]

Experts are in the process of developing “biomarkers” (biological markers) in order to recognise a presence of the disease. Examples of biomarkers being researched for disease confirmation are beta-amyloid and tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid with changes in brain injuries. These biomarkers have been suggested to change throughout the course of the disease process. Biomarkers have yet to be validated.

Neuro-imaging[edit | edit source]

Standard imaging used to detect brain changes in patients includes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). Imaging is primarily used to rule out other conditions which although similar to Alzheimer’s would require different treatment such as tumours, small or large strokes and trauma or fluid in the brain. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Proteins CSF can be observed through a lumbar puncture or spinal tap. Research suggests that throughout early stages of Alzheimer’s disease changes in CSF involving two proteins (beta-amyloid and tau) promote abnormal brain deposits linked to the disease. A challenge faced by researchers is the variance among protein levels observed between institutions. Research is currently being performed to set standards for CSF proteins in relation to Alzheimer’s disease.

Genetic Testing[edit | edit source]

Three genes rare genes have been linked to causing Alzheimer’s Disease such as Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), Presenilin-1 (PS-1), Presenilin-2 (PS-2). Another gene associated with a high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease is Apolipoprotein 4 (APOE-4). Genetic testing is not currently recommended outside of research because there are no current treatments that can alter the course of Alzheimer’s.

The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) criteria for amyloid imaging:

Structural Imaging[edit | edit source]

- Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease have significant shrinking with disease progression

- Significant shrinking in the hippocampus may be a sign of early onset Alzheimer’s

- No standards have been set regarding values for shrinking size to dictate Alzheimer’s disease

Functional Imaging[edit | edit source]

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and other functional methods suggest decreased brain cell activity in individuals with AD

- Decreased blood sugar observed in areas important for memory, learning and problem solving

- No standards have been set regarding values for inactivity to confirm Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Imaging[edit | edit source]

- Biological cues may indicate the progression of Alzheimer’s disease before changes in brain structure or function, a change in memory, thinking and reasoning

- Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB), Amyvid, Vizamyl or Neuraceq Since 2012 have been developed to recognise amyloid plaque.While amyloid plaque can be recognized under positron emission tomography (PET) this cannot be used as a diagnostic criteria as not all individuals with amyloid plaque have symptoms.

- Therefore, tracers are currently not recommended in diagnosing individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease.

Screening Tools[edit | edit source]

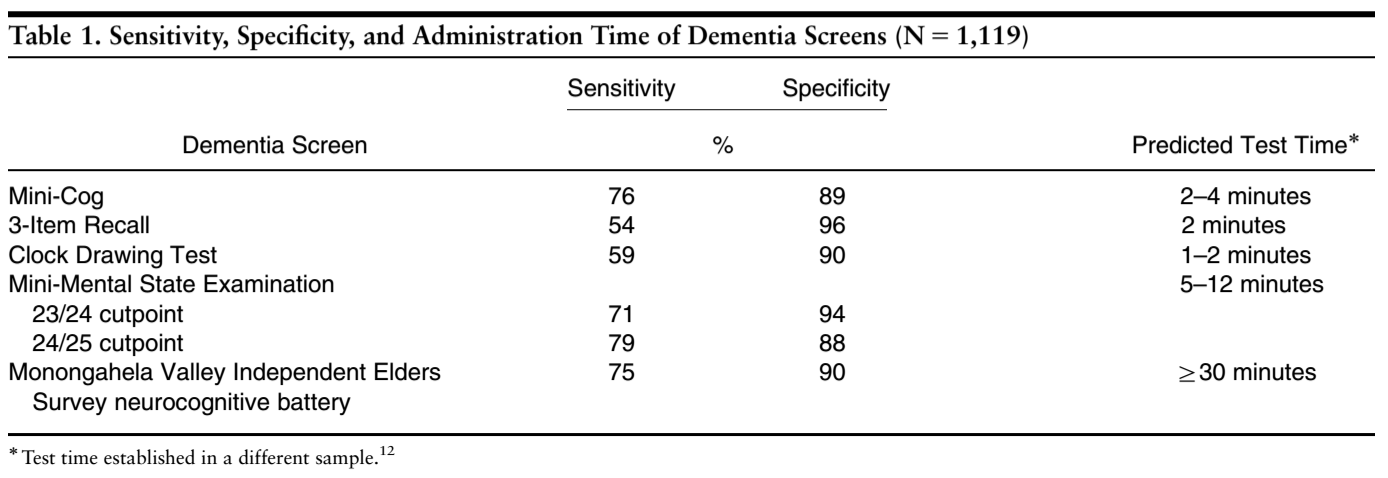

Objective tools have been validated in the practice of physical therapy in order to screen for AD such as the Mini-Cog, Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Clock-Drawing, & Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Exam. Screening tools can be chosen based upon sensitivity, specificity and time to administer the screen.

Mini-Mental State Exam was validated for detecting possible dementia, however time to administer the exam keeps physicians from using it. The MMSE takes 5-12 minutes to administer and is composed of 20 questions in 5 categories to observe orientation, memory, attention-concentration, language and constructing[31].

- Cut off scores: (out of 25)

- ≥ 24 = no impairment

- 18-23 = mild impairment

- ≤ 17 = severe impairment

- < 23 is generally accepted as indicating cognitive impairment and was associated with the diagnosis of dementia in at least 79% of cases (Lancu & Olmer, 2006) [32]

Mini-Cog takes 2-4 minutes to administer and combines constructing (clock drawing) and memory. [33]

- Below are current findings for ruling the differential diagnosis of AD in or out, due to how the tests perform in terms of sensitivity, it would be best to cluster these tests in order to rule in the possibility of dementia or AD.

- A score < 3 indicates clinically meaningful cognitive impairment in a score out of 10

Causes[edit | edit source]

The definitive cause of Alzheimer’s disease is still unknown. It is believed that early onset Alzheimer’s is caused by a genetic mutation. Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is caused by complex changes that occur in the brain over a period of time. It is believed that a combination of factors from the environment, genetic, and lifestyle. The importance a single factor may play on an individual is different among everyone with the disease. Refer to risk factors under Characteristics/ Clinical Presentation above for further information. [35]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

The most noticeable symptoms initially are the cognitive and memory-related symptoms. However, Alzheimer's disease can affect other parts of the body causing symptoms other than those affecting memory and cognition. Often abnormal motor signs can be apparent depending on the area of the brain affected by the disease. The presence of tremors can be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline, the presence of bradykinesia with increased risk for functional decline, and the presence of postural-gait impairments with increased risk of institutionalization and death. Additionally, patients may develop disorders of sleeping, eating, and sexual behavior.[36]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer's Disease, so medical management is focused on maintaining the quality of life, maximizing function, enhancing cognition, fostering a safe environment and promoting self engagement[37]. Maximizing dementia functioning involves monitoring the patient's health and cognition, patient and family education, initiation of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.

- Cognitive symptom treatment

- Although the disease progression cannot be altered, it may be slowed by the pharmacological medication listed above

- Behavioral and psychological symptom treatment

- Agitation, aggression, depression, and psychosis are the primary cause of assisted living or nursing home placement.

- Assessment of behaviors occurring suddenly is important to increase patient comfort, security, and ease of mind.

- Monitoring Alzheimer’s disease

- Patients should return on a regular basis in order for the physician to monitor the course of Alzheimer’s disease (behavioral and cognitive changes).

- Regular follow-up appointments allow for the adaptation of treatment styles to fit the needs of the patient.

- Nonmedical/social Issues the patients need to address:

- Need for ongoing support & information

- A living will or power of attorney

- Review of finances/planning for future and end of life care

- Alternative Treatment

- There are concerns regarding alternative treatments in addition to physician-prescribed medicine. If any concerns are questions brought to attention, the physician should be notified.

- Importance of Caregiver

- Many caregivers seek to meet the needs of the physician and the patient which increases rates of stress and depression. Physicians should continue to monitor the status of the caregivers watching out for burnout and providing them with resources as well.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

It is important to modify risk factors that can be changed through lifestyle activities. Hypertension has been shown to interact with a particular genotype that is at risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. This interaction increases amyloid deposition in cognitively healthy middle-aged and older adults. Thus, when at-risk it is important to manage blood pressure, which can be done through exercise[39].

Physical activity is important to incorporate in a patient’s with Alzheimer’s disease life, and the sooner the better. “Earlier application of physical activity to mitigate pathological processes and to assuage cognitive decline is imperative given recent evidence from clinical trials suggesting that interventions applied earlier in the course of Alzheimer's Disease are more likely to achieve disease modification, whereas those applied later have a significant but more limited effect after the emergence of neuronal degeneration.”[40]

A community-based exercise program has been shown to improve multiple domains of life for individuals with Alzheimer's. In a study by Vreugdenhil et al., community-dwelling individuals with Alzheimer's added a daily home exercise program and walking under supervision to a usual treatment plan. Those participating in the additional exercise improved cognition, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living[41].

It has been suggested that aerobic exercise in the form of walking and upper limb cycle ergometer, in particular, helps to improve exercise tolerance as well as quality of life in individuals with Alzheimer's[42]. Strength training in addition to aerobic training has been supported in the research. The combination of both activities have shown greater improvements in cognition than aerobic training alone[43].

Individuals with dementia are at an increased risk for falling compared to the average population of community-dwelling older adults. [44] Preliminary research has been conducted looking at falls prevention training for individuals with intellectual disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. A study found that using a modified Otago Exercise program was effective at decreasing falls risk for some adults with intellectual disabilities[45]. A pilot study found that the Berg Balance Scale had relative reliability values that support its use in clinical settings. However, MDC values are not established for this population[46]. More research is needed in this area to best assess falls risk in this population.

Frequently, when a physical therapist works with a patient who has been diagnosed with an Alzheimer's, the patient may be in a structured living environment because they have progressed to a stage in the disease where their caregivers can not give the patient the proper attention that they need. Physical therapy can provide the patient with an activity that the patient can perform successfully at and it also can help to improve their breathing, mobility, and endurance. Restlessness and wandering can be typical of patients with Alzheimer's patients and may be managed with physical therapy (by releasing some of the energy through exercises). These exercises can help to reduce the night time wanderings called sundowning.

Transition Care[47] provides time-limited, goal-oriented and therapy-focused packages of services to older people after a hospital which includes low-intensity therapy—such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy—social work and nursing support or personal care. It is designed to improve independence and functioning in order to delay their entry into residential aged care. A qualitative research study suggests better outcomes in older patients (above 80yrs) with family participation to assist physiotherapy care in a Transition care setting[48].

Group therapy is also successful with patients with Alzheimer's disease, but the session must not provide more stimulation than the patient is able to tolerate. Repetition and encouragement are also very important to help keep the patient's confidence high and to help with remembering the exercises. Knowing the patient is important to the therapist because it can allow for better communication, by using words and terms that the specific patient may be more familiar with. The Preferred Practice Pattern is 5E: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Progressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System. The physical therapist can use the Global Deterioration Scale to assess the level of dementia. When a patient with Alzheimer's is placed in a comprehensive cognitive stimulation program it enhances the neuroplasticity of the patient. The exercise can also help to improve mobility, balance, and ROM for the patient as well as improve the mood[49].

Staying physically and socially active can possibly help to decrease the risk of dementia along with staying mentally active. A randomized controlled trial showed favorable outcomes with exercise and horticultural intervention programs for older adults with depression and memory problems[50].

Dietary Management[edit | edit source]

It has been found that maintaining a healthy diet may help to prevent or slow the progression of Alzheimer's. It is suggested that the diet be low in fat, high in omega-3 oils, and high in dark vegetables and fruits, also adding vitamin C to the diet along with coenzyme Q10, and folate may work to lower the risk of Alzheimer's. There does not seem to be one single aspect of diet that provides neuroprotection, rather that the items work together to decrease risk of AD.[51]There is also some interest in the use of antioxidants such as vitamin E and ginkgo, along with anti-inflammatory agents, and estrogen replacement therapy for women.[52]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Pick's Disease

- Lewy Body Dementia

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Dementia from multiple medications

- Other potentially reversible causes of dementia

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Alzheimer's Disease & Dementia [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from:http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp

- ↑ Anand, R., Gill, K.D. and Mahdi, A.A. (2014) 'Therapeutics of Alzheimers disease: past, present and future', Neuropharmacology, 76, 27-50

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Alzheimer's Disease & Dementia [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp

- ↑ Porth C. Pathopysiology Concepts of Altered Health States. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott and Wilkins; 2005.

- ↑ actionalz. What is Alzheimer's Disease?. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Wv9jrk-gXc [last accessed 08/12/12]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 wenk, G.L. (2003) 'Neuropathological changes in Alzheimers disease', Journal of clinical psychiatry, 64, 7-10

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Reitz C, Mayeux R. Alzheimer disease: Epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, risk factors and biomarkers. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014, 88; 4: 640-651. Accessed 21 November 2018.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Latest Alzheimer's Facts and Figures [Internet]. Latest Facts; Figures Report | Alzheimer's Association. 2016 [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/facts/

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Latest Alzheimer's Facts and Figures [Internet]. Latest Facts & Figures Report | Alzheimer's Association. 2016 [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/facts/

- ↑ Naharci MI, Buyukturan O, Cintosun U, Doruk H, Tasci I. Functional status of older adults with dementia at the end of life: Is there still anything to do?. Indian journal of palliative care. 2019 Apr;25(2):197.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Alzheimer's & Dementia Testing Advances | Research Center [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr2]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/research/science/earlier_alzheimers_diagnosis.asp

- ↑ Alzheimer's and Dementia Causes, Risk Factors | Research Center [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/research/science/alzheimers_disease_causes.asp#apoe

- ↑ Alzheimer's and Dementia Causes, Risk Factors | Research Center [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/research/science/alzheimers_disease_causes.asp#apoe

- ↑ Latest Alzheimer's Facts and Figures [Internet]. Latest Facts; Figures Report | Alzheimer's Association. 2016 [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/facts/

- ↑ Traumatic Brain Injury | Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis [Internet]. Dementia. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/dementia/traumatic-brain-injury-head-trauma-symptoms.asp

- ↑ Latest Alzheimer's Facts and Figures [Internet]. Latest Facts; Figures Report | Alzheimer's Association. 2016 [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/facts/

- ↑ Duthie A, Chew D, Soiza RL. Non-psychiatric comorbidity associated with Alzheimer's disease. Qjm [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017Apr1];104(11):913–20. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/104/11/913/1563428/Non-psychiatric-comorbidity-associated-with

- ↑ Duthie A, Chew D, Soiza RL. Non-psychiatric comorbidity associated with Alzheimer's disease. Qjm [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017Apr1];104(11):913–20. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/104/11/913/1563428/Non-psychiatric-comorbidity-associated-with

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Know the 10 Signs of Alzheimer's Disease [Internet]. Know the 10 Signs of Alzheimer's Disease. [cited 2017Apr3]. Available from: http://alz.org/10-signs-symptoms-alzheimers-dementia.asp

- ↑ Porth C. Pathopysiology Concepts of Altered Health States. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott and Wilkins; 2005.

- ↑ Stages of Alzheimer's Symptoms [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_stages_of_alzheimers.asp

- ↑ Duthie A, Chew D, Soiza RL. Non-psychiatric comorbidity associated with Alzheimer's disease. Qjm [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017Apr1];104(11):913–20. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/104/11/913/1563428/Non-psychiatric-comorbidity-associated-with

- ↑ Porth C. Pathopysiology Concepts of Altered Health States. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott and Wilkins; 2005.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Alzheimer's & Dementia Testing Advances | Research Center [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr3]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/research/science/earlier_alzheimers_diagnosis.asp

- ↑ Benson AD, Slavin MJ, Tran T-T, Petrella JR. Screening for Early Alzheimer's Disease: Is There Still a Role for the Mini-Mental State Examination? The Primary Care Companion [Internet]. [cited 2017Apr1]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1079697/

- ↑ Rehab Measures - Mini-Mental State Examination [Internet]. The Rehabilitation Measures Database. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=912

- ↑ Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a Screen for Dementia: Validation in a Population-Based Sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(10):1451–4.

- ↑ Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a Screen for Dementia: Validation in a Population-Based Sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(10):1451–4.

- ↑ About Alzheimer's Disease: Causes [Internet]. National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [cited 2017Apr3]. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/topics/causes

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Medical Management and Patient Care [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. [cited 2017Apr1]. Available from: http://www.alz.org/health-care-professionals/medical-management-patient-care.asp

- ↑ Pollom E, Little J. PT Management of Alzheimer's Disease [Internet]. YouTube. YouTube; 2017 [cited 2017Apr2]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rW3rQ73rQFE&t=8s

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Phillips, C. et al. "The Link Between Physical Activity And Cognitive Dysfunction In Alzheimer Disease". Physical Therapy 95.7 (2015): 1046-1060. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Vreugdenhil, Anthea et al. "A Community-Based Exercise Programme To Improve Functional Ability In People With Alzheimer’S Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 26.1 (2011): 12-19. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Mahmoud S. “Role of aerobic exercise training in changing exercise tolerance and quality of life in Alzheimer's disease”. European journal of general medicine. 2011;8(1):1-6. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Manckoundia, Patrick et al. "Impact Of Ambulatory Physiotherapy On Motor Abilities Of Elderly Subjects With Alzheimer's Disease". Geriatrics;; Gerontology International 14.1 (2013): 167-175. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Renfro M, Bainbridge D, Smith M. Validation of Evidence-Based Fall Prevention Programs for Adults with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disorders: A Modified Otago Exercise Program. Frontiers in Public Health. 2016;4. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Muir-Hunter S, Graham L, Montero Odasso M. Reliability of the Berg Balance Scale as a Clinical Measure of Balance in Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer Disease: A Pilot Study. Physiotherapy Canada. 2015;67(3):255-262. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Renfro M, Bainbridge D, Smith M. Validation of Evidence-Based Fall Prevention Programs for Adults with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disorders: A Modified Otago Exercise Program. Frontiers in Public Health. 2016;4. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Transition Care Programme. Aging and aged care.Accessed from ☀https://agedcare.health.gov.au/programs-services/flexible-care/transition-care-programme on 4/12/2019.

- ↑ Lawler K, Taylor NF, Shields N. Family-assisted therapy empowered families of older people transitioning from hospital to the community: a qualitative study. Journal of physiotherapy. 2019 Jun 13.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Makino K, Nakakubo S, Liu-Ambrose T, Shimada H. Exercise and Horticultural Programs for Older Adults with Depressive Symptoms and Memory Problems: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Jan;9(1):99.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Porth C. Pathopysiology Concepts of Altered Health States. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott and Wilkins; 2005.

</div>