Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

Original Editor Philip Langridge Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Andeela Hafeez, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Philip Langridge and Adam Vallely Farrell

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis is a condition characterised by an exaggerated response of the immune system (a hypersensitivity response) to the fungus Aspergillus (most commonly Aspergillus fumigatus).[1]

This is a condition where a patient develops an allergy to the spores of Aspergillus moulds. Predominantly it affects asthma patients but also cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis patients.[1][2]

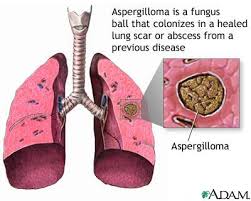

Allergic Broncho-Pulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) is a condition for which there is, as yet, no complete cure, so it is managed using steroids and antifungals in order to avoid any lung damage. The fungus takes up residence in the lungs and grows in the air spaces deep within. The fungus does not invade the lung tissue itself (it is non-invasive) but sets up a permanent source for irritation and allergic reaction.

Sufferers of ABPA find anywhere that has increased levels of airborne mould spores can trigger severe asthmatic reactions - e.g. compost heaps, damp buildings and even the outside air in some places at particular times of the year. Avoiding over-exposure - staying indoors or using a protective face-mask may be advisable to minimise exacerbation of symptoms.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

For unclear reasons colonization in these patients prompts vigorous antibody (IgE and IgG) and cell-mediated immune responses (type I, III, and IV hypersensitivity reactions) to Aspergillus antigens, leading to frequent recurrent asthma exacerbations.[3][4] The disorder is characterized histologically by mucoid impaction of airway, eosinophilic pneumonia, infiltration of alveolar septa with plasma and mononuclear cells, and an increase in the number of bronchiolar mucous glands and goblet cells. Aspergillus in patients with established cavitary lesions or cystic airspaces; and from the rare Aspergillus pneumonia, which occurs in patients who take low doses of prednisone long term (eg, patients with COPD). Although the distinction can be clear, overlap syndromes have been reported.[5]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Due to poor collection of community data the true prevalence of ABPA is mainly speculative[6]. Data, based on secondary care referrals, in South Africa, Ireland, Saudi Arabia, New Zealand and China estimate the prevalence to be about 1–3.5%.[7]

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

The main clinical observations of ABPA are episodic airway obstruction, chest pains, fever, fatigue, a cough which is often associated with increased sputum production. As well as copious amounts of sputum, brown mucous plugs may also be visible.[8] It is often difficult to differentiate in patient's who have asthma and cystic fibrosis as the symptoms are similar to acute exacerbations of these predisposing conditions, hence the need for a systematic and thorough diagnosis.[8]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There are different criteria that have been suggested as indicative of ABPA. The most commonly used is a criteria suggested by Patterson et al.[9]

If a patient has all eight of the symptoms below then a diagnosis is certain.[9][10] If a patient has seven, diagnosis for ABPA is highly likely. If the patient has asthma, eosinophilia and a history of infiltrates then ABPA should be considered as possible and the other tests can be done to attempt to confirm. In cases where a patient has fewer than seven of the above diagnosis becomes less sure. If a quick answer is needed or preferred and if the health of the patient allows then biopsy provides a very good way of deciding the diagnosis[9]:

- Episodic wheezing (asthma)

- Eosinophilia (increase in the number of certain white blood cells which fight disease)

- Immediate skin test reactivity to Aspergillus antigens

- Precipitating (IgG) antibodies to Aspergillus

- Elevated total IgE

- Elevated Aspergillus-specific IgE

- Central bronchiectasis (widening of the airways)

- History of pulmonary infiltrates (seen on X-ray)

Objective diagnosis:[edit | edit source]

- Chest x-rays or CT[2]

- Examination of a sputum sample

- Blood tests

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment consists of long term use of steroids (e.g. prednisolone) to reduce inflammation and lung damage[11]. There are several potential difficulties with the use of steroid drugs for long periods but their use is vital to prevent the disease progressing.

We can now often reduce the amount of steroids taken by ABPA patients by giving the patient an antifungal medication such as itraconazole (e.g. Sporanox but there are now several brandnames). This seems to keep the fungus under control and some people can stop taking steroids completely for periods of time.

Another way to reduce the need for steroids is to reduce the inflammation. This is still experimental treatment but a new drug called anti-IgE (omalizumab) has been shown to be effective in a single patient study.[12] This drug works by directly inhibiting a component of the immune system known as IgE. One of the functions of IgE is to promote inflammation and in this case it is permanently switched on by the aspergillosis infection, so the inflammation is permanently present and causes scarring (IgE would normally be switched off after a few days). Inhibiting IgE with omalizumab reduces inflammation and thus reduces the need for steroids.[13]

It is known that many asthmatics have fungal allergy problems, a high proportion of these having ABPA, some possibly undiagnosed. The number of those diagnosed with asthma is growing constantly.

Young people with Cystic Fibrosis sometimes also suffer from ABPA, imposing further complications in their treatment.

Sufferers from the genetic disorder Chronic Granulomatous Disorder (CGD) may also be prone to developing Aspergillus infections.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is key in managing the tenacious secretions associated with this disease, whether by support with inhaled medications or instruction in airway clearance techniques. Standard chest physiotherapy is recommended as an adjunct to medical management,[14] The aim of treatment is to aid sputum clearance, increase the efficacy of coughing and manage fatigue. The most common and effective treatments are:

- Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT) is an effective technique and is often used with Postural drainage and manual drainage.[15] Its purpose is to loosen and clear excess pulmonary secretions, improve the effectiveness of a cough and to improve lung ventilation and function. It consists of 3 main stages:

- Breathing Control

- Deep Breathing Exercises or Thoracic Expansion Exercises

- Huffing or Forced Expiratory Technique (FET)[16]

The study by Hoffman L et showed positive outcomes with inspiratory muscle training in patients with advanced lung disease[17]

- Forced expiration technique, also known as a huff can be used on its own or as part of the ACBT. A huff is very effective at clearing secretions especially when combined with other airway clearance techniques.[18]

- Manual Therapy is a popular treatment technique and is often used when the patient is fatigue or experiencing an exacerbation of symptoms. It describes techniques that involve external forces to the chest wall to loosen mucus and includes any combination of percussion, shaking, rib springing, vibrations and over pressure. Because of the nature of the technique it is contraindicated in patients that are taking anticoagulants or that have osteoporosis.[19] The aim of treatment is to:

- Loosen secretions

- Reduce fatigue

- Increase the effectiveness of other treatment techniques

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

There is no current cure for ABPA, but management of the inflammation and scarring using itraconazole and steroids usually succeeds in stabilising the symptoms for many years.[20]

ABPA can progress to CPA (chronic pulmonary aspergillosis) which is common non-immunocompromised patients.[21]

This is a relatively 'young' illness (first reported in 1952) with a long period of infection so it takes time for the long term results of improvements in care to become apparent. Identification of a fungal element in other severe asthmas suggests ABPA may well be much more common that was thought. ABPA is starting to lose its image of a rare and unusual infection and hopefully that will lead to increased awareness and improved management of the disease[22].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2009 Mar 1;135(3):805-26.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung_and_airway_disorders/asthma/allergic_bronchopulmonary_aspergillosis.html

- ↑ Greenberger PA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. InAllergy & Asthma Proceedings 2012 May 2 (Vol. 33).

- ↑ Greenberger, P.A., Miller, T.P., Roberts, M. and Smith, L.L., 1993. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with and without evidence of bronchiectasis. Annals of allergy, 70(4), pp.333-338.

- ↑ http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary_disorders/asthma_and_related_disorders/allergic_bronchopulmonary_aspergillosis_abpa.html

- ↑ Ma YL, Zhang WB, Yu B, Chen YW, Mu S, Cui YL. Prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Chinese patients with bronchial asthma. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2011; 34:909–13.

- ↑ Agarwal, R., Chakrabarti, A., Shah, A., Gupta, D., Meis, J. F., … Guleria, R. (2013). Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: review of literature and proposal of new diagnostic and classification criteria. Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 43(8), 850–873.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Stevens D A, Moss R B, Kurup V P Participants in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Conference et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis—state of the art: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Conference. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 37 (Suppl 3) S225-S26

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Halwig JM, Liotta JL, Roberts M (1986) Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Natural history and classification of early disease by serologic and roentgenographic studies. Arch Intern Med 146: 916–918

- ↑ Agarwal R, Maskey D, Aggarwal AN, Saikia B, Garg M, Gupta D, Chakrabarti A. Diagnostic performance of various tests and criteria employed in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a latent class analysis. PLoS One. 2013 Apr 12;8(4):e61105.

- ↑ Greenberger PA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002 Nov 1;110(5):685-92.

- ↑ Kanu A, Patel K. Treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) in CF with anti‐IgE antibody (omalizumab). Pediatric pulmonology. 2008 Dec;43(12):1249-51.

- ↑ van der Ent CK, Hoekstra H, Rijkers GT. Successful treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with recombinant anti-IgE antibody. Thorax. 2007 Mar 1;62(3):276-7.

- ↑ Denning DW, Van Wye JE, Lewiston NJ, Stevens DA. Adjunctive therapy of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with itraconazole. Chest. 1991 Sep 1;100(3):813-9.

- ↑ O’Neill B, Bradley JM, McArdle N, et al. The current physiotherapy management of patients with bronchiectasis: a UK survey. Int J Clin Pract 2002;56:34–5

- ↑ Larner E, Galey P. Active cycle of breathing technique. Available from: http://www.nnuh.nhs.uk/publication/download/active-cycle-of-breathing-technique-v3 (accessed 24 April 2019)

- ↑ Hoffman M, Augusto VM, Eduardo DS, Silveira BM, Lemos MD, Parreira VF. Inspiratory muscle training reduces dyspnea during activities of daily living and improves inspiratory muscle function and quality of life in patients with advanced lung disease. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2019 Aug 21:1-1.

- ↑ Van der Schans CP. Forced expiratory manoeuvres to increase transport of bronchial mucus: a mechanistic approach. Monaldi archives for chest disease= Archivio Monaldi per le malattie del torace. 1997 Aug;52(4):367.

- ↑ Diehl N, Johnson MM. Prevalence of Osteopenia and Osteoporosis in Patients with Noncystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis. South Med J. 2016;109(12):779-83

- ↑ Stevens DA, Schwartz HJ, Lee JY, Moskovitz BL, Jerome DC, Catanzaro A, Bamberger DM, Weinmann AJ, Tuazon CU, Judson MA, Platts-Mills TA. A randomized trial of itraconazole in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000 Mar 16;342(11):756-62.

- ↑ Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with asthma and its complication chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in adults. Medical mycology. 2013 May 1;51(4):361-70.

- ↑ Asano K, Kamei K, Hebisawa A. Allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis–pathophysiology, histology, diagnosis, and treatment. Asia Pacific Allergy. 2018 Jul 23;8(3).