Ageing and Genitourinary System

Introduction[edit | edit source]

With aging, an interplay between the genatics, environment and celluar dysfunction leads to age related functional and structural changes.[1]

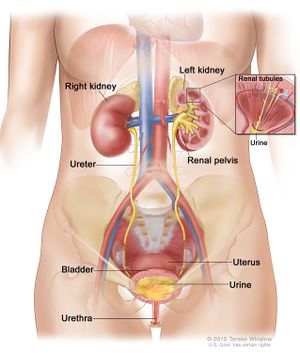

Kidneys[edit | edit source]

Changes that occur in the kidney with aging include thickening in the Bowman’s capsule and impaired permeability, degenerative change in the tubules, atrophy and decreased number of nephrons and vascular changes at all vessels levels.

Renal efficiency in waste disposal is impaired due to:

- Halving of the number of nephrons in an average life span

- Renal blood flow is halved by 75 years

- Glamerular filtration rate and maximum excretory capacity is reduced by the same proportion

The aging kidney can maintain normal homeostatic mechanisms and waste disposal within limits, but it is less efficient, needs more time and has minimal reserves. Therefore, minimal dehydration, infection or impaired cardiac output may lead to kidney failure.[2]

Prostate[edit | edit source]

With aging prostatic atrophy occurs with focal areas of hyperplasia.

Benign nodular hyperplasia is present in 75% males over 80 years.

Histological (latent) prostatic carcinoma is present in most males above 90.[2]

Bladder[edit | edit source]

Increased dysfunction with aging includes reduction in bladder capacity.

Unihibited contractions and decreased urinary flow rate, so the person experiences the need to empty the bladder more frequently.[2]

Urinary Tract Infections[edit | edit source]

Urinary tract infections are common infections seen in older people admitted to the hospital after fall or acute confusion. They are a common cause of re-admission and can also result in a prolonged stay in the hospital as the urinary tract infection have a more systemic effect on older people leading older adults to have symptoms like fatigue and decreased mobility, with patients reporting that they are simply “off their legs".[2]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

First try to ensure that the person is not self-dehydrating for fear of wetting themselves, which is more common if the person knows he will be going out or to decrease the need for the toilet at night.

People with incontinence may tend to not participate fully in the session, especially in unfamiliar environments. Also, dehydration and infection can lead to complication of acute confusion or pain.

This has implications on consent to treatment.

If the person has a catheter on, check that it is empty and secured to their legs (though not too tightly) and not to the chair. Maintain dignity throughout treatment, though it is not always possible if the person has a visible night bag. You may have to deal with their embarrassment and depression because of their incontinence. Discussion with the patients about their issues is part of our role, but if you are not comfortable doing it, refer the person to another individual who has the required skills.

To protect your health and safety, watch how you handle body waste and try to keep an extra pair of rubber gloves in your uniform pocket. Each Trust has an infection control policy to be adhered to.[2]

Resources[edit | edit source]

To download the PDF click here Ageing and Genitourinary System

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ O’Sullivan ED, Hughes J, Ferenbach DA. Renal aging: causes and consequences. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2017 Feb 1;28(2):407-20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Ageing and Genitourinary System