APA Clinical guide to safe manual therapy practice in the cervical spine 2017

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Manual therapy can form an important instrument of the physiotherapy tool kit when managing patients with neck pain disorders. Although rare, the risk of catastrophic adverse effects has been associated with manual therapy of the cervical spine. The most serious associated adverse events include cervical artery dissection (CAD) and vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI), both of which can lead to stroke.

The purpose of this Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) clinical guide is to assist physiotherapists to practice safe manual therapy within the cervical spine region with the awareness and knowledge to be able to manage the risks and recognise early warning signs of adverse events.[1][2] The guide is divided in two parts - vascular considerations and high velocity manipulation techniques.

(i) Cervical Artery Dissection - CAD[edit | edit source]

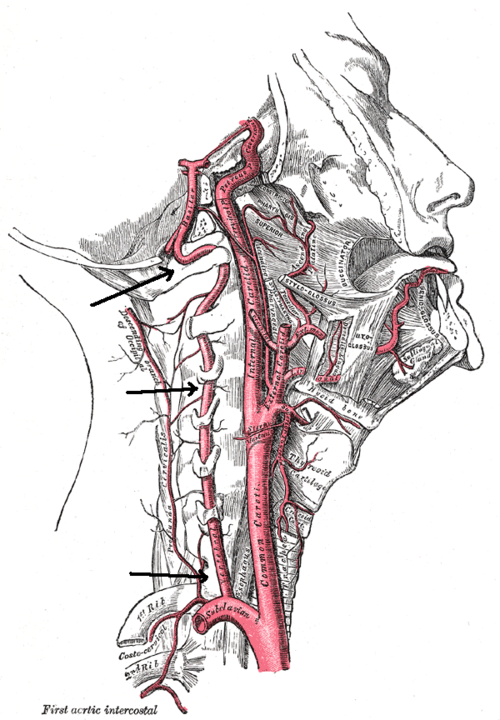

CAD describes a tear, that can vary in severity, in the arterial wall of a main vessel that supplies blood to the brain. It is more common for CAD to effect the vertebral artery rather than the internal carotid however dissection in either can be fatal. Blood clots are often dislodged and travel to the brain causing cerebrovascular blockage.

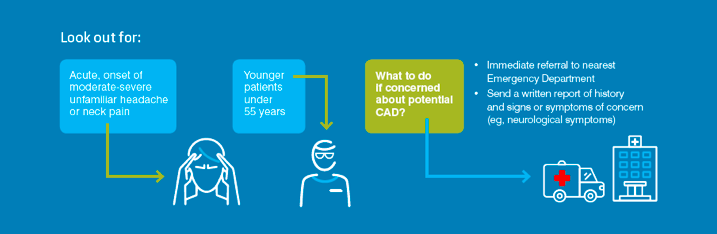

Patient risk is increased with recent minor trauma, infection, genetic factors, migraine and cardiovascular risk factors. The patient demographic is usually under 55 years old and the pain pattern is a sudden onset of moderate to severe pain that does not subside. Therapists should be aware and ask patients about recent exposure to minor trauma (such as neck sprains or sporting injuries), recent unfamiliar neurological symptoms or recent infections.

(ii) VBI - Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency[edit | edit source]

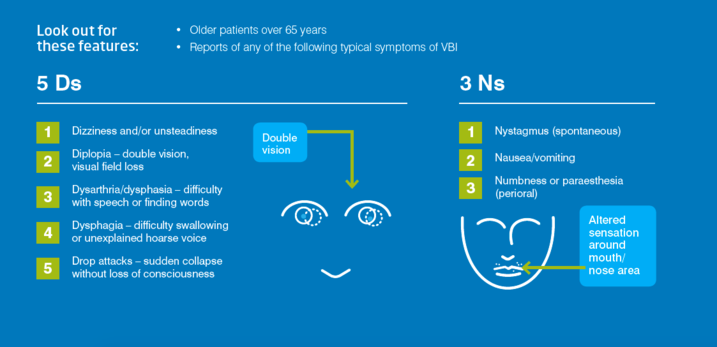

VBI is associated with a patient group that are over 65 years old with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and/or hypercholesterolemia and smoking history. However, it can be associated with CAD and occur at any age. The symptoms of VBI include dizziness and/ or unsteadiness, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia and sudden collapse without loss of consciousness (drop attacks). These symptoms are the result of inadequate blood supply reaching the hindbrain. [3]

Positional testing can be performed to ascertain whether the patient is suspected to have VBI. If testing is positive, best practice is to treat within a range that does not provoke symptoms and avoid end of range neck positions during any therapy or exercises. Learn how to test - Vertebral Artery Testing.

Important early warning features of VBI to monitor your patient for are:

- sudden onset headache and/or neck pain

- unfamiliar and/or progressive neurological symptoms - 5 Ds 3 Ns

- D1 - Dizzyness/ unsteadiness

- D2 - Diplopia - double vision and/or visual field loss

- D3 - Dysarthria/dysphasia

- D4 - Dysphagia

- D5 - Drop attacks (sudden loss of consciousness)

- N1 - Nystagmus

- N2 - Nausea/vomiting

- N3 - Numbness/ parathesia (perioral)

- Horner's Sign

- Anything else about patient presentation that causes any clinical concern

Vascular Considerations[edit | edit source]

The vascular considerations component of the clinical guide is summarised in the flow chart below defining the process of recognition and the optimal action plan if you suspect CAD or VBI in your patient. These figures have been taken directly from the APA website.

The APA website is a great resource for all physiotherapists. This guide can be found on their website outlining the safe manual therapy practice when treating neck disorders.

High velocity manipulation techniques[edit | edit source]

High velocity manipulation techniques (HVMT) have proven efficacy in the management of some patients with neck pain disorders. Regardless of the potential positive impact for the patient, it is imperative to be able to recognise situations where HVMT is contraindicated or puts the patient at risk. As a clinician it is within our scope to practice at a level of risk if the practice is justified by current evidence, can be clinically reasoned and patient has provided their informed consent.

The contraindications and precautions to HVMT to consider include:

- all red flags until proven otherwise

- suspected CAD or high risk of CAD

- VBI

- advanced degenerative disease (with or without neurological signs)

- recent major trauma

- segmental instability

- previous spinal surgery

- marked muscle spasm around the neck

- bone disease & reduced bone integrity (osteoporosis, osteopenia)

- pregnancy/ post partum period

Further Reading (as suggested by APA)[edit | edit source]

Acknowledgements[edit | edit source]

The Physiopedia team acknowledge the Australian Physiotherapy Association and specifically the authors of this guide: Dr Lucy Thomas, Dr Debra Shirley & Professor Darren Rivett. Written permission has been received to reproduce this material.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jull, Gwendolen A., Sterling, Michele, Falla, Deborah, Treleaven, Juliaand O'Leary, Shaun(2008).Whiplash, headache, and neck pain: Research-based directions for physical therapies.1st ed.Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone:Elseiver Limited.

- ↑ Rushton A, Rivett D, Carlesso L, Flynn T, Hing W, Kerry R. 2012. International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region for potential of Cervical Arterial Dysfunction prior to Orthopaedic Manual Therapy Intervention.

- ↑ Treleaven J. 2017. Dizziness, Unsteadiness, Visual Disturbances, and Sensorimotor Control in Traumatic Neck Pain. Journal of Orthopedic Sports Physical Therapy. Jul;47(7):492-502. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7052. Epub 2017 Jun 16.