ACL Rehabilitation: Acute Management after Surgery

Original Editor - Mariam Hashem

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Chelsea Mclene, Tony Lowe, Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti, Jorge Rodríguez Palomino, Rachael Lowe, Leana Louw and Wanda van Niekerk

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Anterior Cruciate Ligament injury is one of the most common injuries among different sports with more than 200000 injuries in the US, 65% of these go under reconstructive surgery[1]. In football , the range of ACL injuries has been estimated to range from 0.06 to 10 injuries per 1000 game hours. Professional athletes are more prone to ACL injures[2]. Most injuries occur when the opposite team has the ball and the players are defending with tackling and cutting are considered the most common playing actions associated with the injury (51% and 15% respectively).

Females are at a higher risk [3] due to many factors such as higher valgus stress and loading in females when performing tasks, differences in hamstring/quadriceps strength ratio and vastus lateralis/semitendinous strength ratio, lateral and posterior hip insufficiencies, and non-dominant leg strength differences[4]. However, a case series report by Brophy et al reported no differences between the genders[5]. The difference between male and female athletes according to this report was in the mechanism of injury; males were more likely to suffer contact injuries (56%) while non-contact injuries were dominant among female players.

In other sports, the incidence rates vary. In skiing, ACL injury represent 30.9 per 100,000 skiers per day[6]. While in basketball, 17 per 100,000 athletic exposures were reported between 1989 and 2004 in the USA[7].

Modern approaches of surgery have shifted towards rehabilitation-modified surgery. So that surgery is designed to facilitate early mobilisation and return to normal function. Prior, it was required to keep joint immobilised for some time to protect graft and surgery, sacrificing performance and muscle function[8].

Instability, knee OA, inability to return to sport (only 65% of NFL players are able to regain pre-injury performance)[9] and recurrence are among the short and long term list of consequences that follow ACL injury.

OA after injury is reported to be very high, reaching 50-100%, in both conservative and surgical management[10]. Changes in loading mechanism following the injury are considered to be a contributing factor to developing OA. Walking with decreased force on the injured limb, both on medial and lateral knee compartments, was observed following the injury[11]

Rehabilitation is highlighted as the most crucial factor in the management of ACL injury, superior to surgical reconstruction[12]. A well-performed ACL reconstruction doesn't guarantee successful outcomes unless followed by a quality rehabilitation[13]. The differences are reported to be minimal between rehab after reconstruction or rehabilitation alone with regards to function, return to sport, and re-injury[14].

Pre-Surgical Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

ACL reconstruction or repair when the athlete had prior good knee function is associated with good post-surgical outcomes[15]. Start immediately after injury, assess the condition carefully using objective measures to track progress and changes.

The following are goals of ACL pre-surgical rehabilitation and are predictive of good post-operative outcomes:

- Full knee extension ROM

- Absent or minimal effusion

- Absence of extension lag during SLR.

Pre-operative rehabilitation should be built on aggressive quadriceps strengthening with the aim of increasing quadriceps index > 90% ( the ratio of injured-side quads strength to contra-lateral side quads strength)[8].

Make sure your patient is mentally prepared for surgery. Spend quality time educating your patient on their injury, surgical procedure, home program, rehabilitation process and outcomes[16].

Considerations Before Designing Post-Surgical Rehabilitation Program[edit | edit source]

ACL injury is often a complex presentation combined with other associated damages such as meniscus injury, medial collateral injury, bone contusion and chondral injury.

The highest recurrence rates of injury and the fact that many players may not be able to return to their prior level of performance challenge the rehabilitation strategy. It is recommended that outcome measures should not be based on a timely manner, instead a clearance to return to sport should be given according to performance levels.

Since it is not a simple injury, a multidisciplinary team is needed to help athletes recover and maintain their level of performance. As a physiotherapist, you should keep communication channels open with the following professionals and know when to refer your patient to them:

- Orthopaedic Surgeon to track your patient progress.

- Sports Psychologist; when the athletes are struggling to return to sport.

- Sports Nutritionist; the time spent away from the field has devastating consequences on muscle mass and body composition. An individualised nutrition plan is also needed to facilitate recovery and return to sport.

Therapist-patient communication cannot be underestimated and is important to engage and motivate the patient. The rehabilitation is time-consuming and can be exhausting and mentally demanding on the patient, so unless the patient is well-motivated, discontinuation is likely to occur[17]. Dr Hägglund et al recommended spending time on the patient's education, goal setting and frequent testing of outcomes for feedback to ensure motivation[18].

Rehabilitation aims to restore maximum performance at the available level of function while minimising the risk of future re-injuries. Thus certain milestones and outcomes are determined in rehabilitation protocols, around which time frames are built to help the athlete return to pre-injury state[8].

Despite the rich body of literature on ACL rehabilitation, the evidence regarding rehabilitation characteristics is still inconclusive.

Acute Management and Goals[edit | edit source]

At this stage (0-6 wks) after surgery, the aim is to protect the surgical repair/reconstruction and prepare the patient for restoring function. The acute management has specific goals that need to be considered:

- Joint Homeostasis

- Scar management

- ROM in all directions

- Quadriceps independent work and terminal extension range

- A long term plan for 6-9 months of recovery. To draw a map for your patient and to determine time-specific milestones that would help in designing your program.

Protection of the post surgical repair is done by the following:

- Limiting ROM to 90° until the femoral and/or adductor nerve block is off (it usually takes 48-72 hours). Once the patient can report accurate sensation, ROM is allowed with regards to patient comfort. Passive ROM is allowed in all directions, possibly using a CPM device[19], since it doesn't place any negative stress on the ligament[20].

- Bracing in an immobiliser until femoral/adductor nerve block is off, then change to a hinged-knee brace for 3-7 days or until the patient is able to perform terminal knee extension, depending on the time you see your patient. Bracing remains a great area of controversy. A systematic review by Kruse et al[21] concluded that bracing adds to the cost of rehabilitation with little or no advantage.

- Partial Weight Bearing is recommended for two weeks after surgery to minimise swelling and inflammation and allow full resolution of effusion. Reaching full weigh-bearing at the first 6 weeks post-surgical is associated with high IKDC scores[22].

- Stationary Bike without resistance is introduced on day 10, or when the patient achieves >110° passive flexion[10]

- Complete weight bearing strength training is delayed up to 6 weeks.

Refer to this article for further information on the different phases of ACL rehabilitation.

Homeostasis[edit | edit source]

A joint with abnormal homeostasis would typically be painful, swollen and stiff. Loading a normal joint will result in normal responses, however, in the presence of post-surgical inflammation the loading response will be devastating and can result in drastic events. Frequent evaluation of activities and slowing down whenever a sign of overloading is present is required to restore homeostasis as soon as possible[23].

Restored homeostasis is crucial to prevent the following consequences:

- Limited ROM, particularly flexion. Extension could be limited due to other factors such as meniscus injury.

- Inhibited neuromuscular firing pattern of quadriceps.

- Abnormal scar healing as a result of prolonged inflammatory phase.

- Unrestored homeostasis can lengthen the entire rehab process.

To restore homeostasis, activities and exercise should be within normal or low load to avoid stressing the healing tissue. You can also incorporate various modalities in the rehabilitation program such as lymphedema massage, pneumatic compressive devices, elevation, and active muscle pump from the quadriceps and calves[10]. Subsided swelling within 0.5cm of the opposite knee is a milestone that when reached, mobility and balance exercises could be progressed gradually[10].

Scar Management and ROM[edit | edit source]

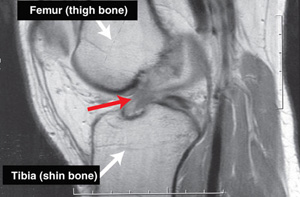

The Anterior Interval lies between the tibia and the inferior border of the patella tendon, and the suprapatellar pouch between the femur and quadriceps tendon. The Anterior Interval has a role to play in providing volume for the joint to move freely throughout the entire ROM. Scar formation, particularly in the proliferation phase up to 6 wks post-surgical, may form in these gaps in a rigid texture resulting in negative consequences such as:

- Restricting ROM and hindering the joint’s ability to move freely by binding patellar tendon and quadriceps tendon gap to the femur and tibia respectively.

- Increases the joint contact pressure, which maybe a contributing factor to anterior knee pain and the long term development of knee OA 10-15 years after surgery.

- Patellofemoral OA, could be developed as early as five years after surgery. Scarring may contribute to this through restricting the anterior knee mobility causing cartilage breakdown when loaded with normal or sport activities.

Scarring also decreases the moment arm of the extensor mechanism, reducing the extension force produced by the quad. This is an important clinical note, because it is a frequent observation that some ACL injured athletes may not be able to regain their quadriceps performance even after 9 months of post-surgical rehabilitation. The reason is simple because of the reduced moment arm due to scar formation. Our role at this point is to guide an organised proliferation of the scar without later consequences on ROM and mobility, this can be facilitated through:

- Early ROM exercises, from the first day after surgery, to create a pressure gradient within the knee; flushing blood and inflammatory cells created after surgery. ROM in the first four weeks after surgery is correlated with the range gained in later stages of rehabilitation, thus it is important to regain as much as possible in early phases[24]. Passive ROM exercises such as therapist assisted at the end of the bed to get full knee flexion, patient lying on their back assisting with opposite leg to allow maximum available ROM up to the level of patient’s comfort or, wall-slides. Also, a bonus from the elevated position in flushing effusion.

Another example of Passive ROM exercise: flexion using a swiss ball, leg lying straight on table therapist flex the knee till the patient starts reporting symptoms of discomfort or pain or you begin to feel tissue tension. Small oscillations at the end range will eventually help in regaining ROM with time.

Stationary bike as a low load activity is a great tool in the acute phase management. Repeated flexion and extension motions facilitates mobility and smoothes the scar proliferation.

Loss of extension is one of the most common complications. A small degree of knee flexion contracture will restrict the quads ability to regain full strength which is important for functional outcomes. For the quads to work with maximum efficiency, the knee must be able to sustain full extension. Full extension is also necessary for reducing the surface area of load distribution on the entire joint surface in standing and so will decrease arthritis development.

Methods of restoring Extension:

- Manual therapy/mobilisation (posterior femoral glides, screw home mobilisations)

- PROM using external devices

- Soft tissue massage

- Self-Mobilisation: by posterior capsule stretch or using an inverted axillary crutch; heel on axillary pad and leg on arm the patient moves his/her leg into maximum available ROM.

- Patellofemoral mobilisation: up to 10 minutes of patella on femur mobilisation in medial-lateral and superior-inferior directions. This facilitates its mobility, scar mobilisation and helps maintaining the integrity of the suprapatellar pouch.

| [25] | [26] |

| [27] | [28] |

| [29] | [30] |

Restoring Quad Strength[edit | edit source]

Quadriceps activation failure is common following ACL reconstruction, and is often reported bilaterally. The muscle is unable to contract with absence of underlying pathology to the muscle or the innervating nerve, this refers to ''Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI)''[31]. This happens in response to injury and poses a clinical obstacle to rehabilitation.

Decreased quadriceps inhibition was reported after application of several manual therapy techniques[32][33][34]. Cryotherapy, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation and neuromuscular electric stimulation were also used to decrease quads inhibition[35][36].

Facilitating isolated quadriceps contraction by teaching patient how to fire the muscle independently will prevent overlapped firing patterns and compensations from other muscles. Ask patient to glide patella superiorly. This simple exercise, even if it's only a flicker contraction, triggers quadriceps isolated contraction. Building progression from here will aid in performing terminal knee extension which if lost, might manifest itself in a flexed knee gait pattern. Terminal Knee extension is facilitated by asking patient to pop their heel off table.

Create a plan[edit | edit source]

A multi-phasic ACL rehab plan has nine essential phases, each requires a relevant time frame that should be individualized according to athletic needs:

- ROM restoration and protection

- Weight Bearing Tolerance

- Endurance

- Strength

- Power

- Running

- Speed and Agility

- Return to Training

- Return to Play

Remember: Don’t rush rehabilitation. Let it take its time.

Progression to Next Phase[edit | edit source]

The patient is ready to move to the next stage of rehabilitation once the patient is able to demonstrate the following[10]:

- Full active terminal knee extension (0°)

- Flexion within 10° of the contra-lateral side.

- Resolved knee effusion (0.5 cm of contra-lateral knee)

- Able to walk without assistive devices.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2006 May;36(5):267-88.

- ↑ Rochcongar P, Laboute E, Jan J, Carling C. Ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament in soccer. International journal of sports medicine. 2009 May;30(05):372-8.

- ↑ Brophy R, Silvers HJ, Gonzales T, Mandelbaum BR. Gender influences: the role of leg dominance in ACL injury among soccer players. British journal of sports medicine. 2010 Jun 1:bjsports51243.

- ↑ Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt Jr RS, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, Van den Bogert AJ, Paterno MV, Succop P. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine. 2005 Apr;33(4):492-501.

- ↑ Brophy RH, Stepan JG, Silvers HJ, Mandelbaum BR. Defending puts the anterior cruciate ligament at risk during soccer: a gender-based analysis. Sports health. 2015 May;7(3):244-9.

- ↑ Demirağ B, Oncan T, Durak K. An evaluation of knee ligament injuries encountered in skiers at the Uludag Ski Center. Acta orthopaedica et traumatologica turcica. 2004;38(5):313-6.

- ↑ Mihata LC, Beutler AI, Boden BP. Comparing the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury in collegiate lacrosse, soccer, and basketball players: implications for anterior cruciate ligament mechanism and prevention. The American journal of sports medicine. 2006 Jun;34(6):899-904.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Adams D, Logerstedt D, Hunter-Giordano A, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2012 Jul;42(7):601-14.

- ↑ Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Nov 1;48(21):1543-52.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Bousquet BA, O'Brien L, Singleton S, Beggs M. Post-operative criterion based rehabilitation of ACL repairs: A clinical commentary. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2018 Apr 1;13(2).

- ↑ Gardinier ES, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder‐Mackler L. Altered loading in the injured knee after ACL rupture. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2013 Mar;31(3):458-64.

- ↑ Grindem H, Risberg MA, Eitzen I. Two factors that may underpin outstanding outcomes after ACL rehabilitation. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2015;1425-1425.

- ↑ Shelbourne KD, Klotz C. What I have learned about the ACL: utilizing a progressive rehabilitation scheme to achieve total knee symmetry after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2006 May 1;11(3):318.

- ↑ Grindem H, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Nonsurgical or surgical treatment of ACL injuries: knee function, sports participation, and knee reinjury: the Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohort Study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2014 Aug 6;96(15):1233.

- ↑ de Jong SN, van Caspel DR, van Haeff MJ, Saris DB. Functional assessment and muscle strength before and after reconstruction of chronic anterior cruciate ligament lesions. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2007 Jan 1;23(1):21-e1.

- ↑ Shelbourne KD, Klotz C. What I have learned about the ACL: utilizing a progressive rehabilitation scheme to achieve total knee symmetry after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2006 May 1;11(3):318.

- ↑ Heijne A, Axelsson K, Werner S, Biguet G. Rehabilitation and recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: patients' experiences. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2008 Jun;18(3):325-35.

- ↑ Hägglund M, Waldén M, Thomeé R. Should patients reach certain knee function benchmarks before anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? Does intense ‘prehabilitation’before anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction influence outcome and return to sports? British Journal of Sports Medicine 2015;49:1423-1424.

- ↑ Biggs A, Jenkins WL, Urch SE, Shelbourne KD. Rehabilitation for patients following ACL reconstruction: a knee symmetry model. North American journal of sports physical therapy: NAJSPT. 2009 Feb;4(1):2.

- ↑ Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Dunn WR, Kaeding C, Kuhn JE, Marx RG, McCarty EC. ACL reconstruction rehabilitation: a systematic review part I. The journal of knee surgery. 2008 Jul;21(3):217.

- ↑ Kruse LM, Gray B, Wright RW. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2012 Oct 3;94(19):1737.

- ↑ Di Miceli R, Marambio CB, Zati A, Monesi R, Benedetti MG. Do Knee Bracing and Delayed Weight Bearing Affect Mid-Term Functional Outcome after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? Joints. 2017 Dec;5(04):202-6.

- ↑ Van Grinsven S, Van Cingel RE, Holla CJ, Van Loon CJ. Evidence-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2010 Aug 1;18(8):1128-44.

- ↑ Noll S, Garrison JC, Bothwell J, Conway JE. Knee extension range of motion at 4 weeks is related to knee extension loss at 12 weeks after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2015 May 4;3(5):2325967115583632.

- ↑ After Knee Injury or Surgery - Wall Slide Exercises to increase Knee Range of Motion. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b00UCkvYgzE

- ↑ Knee Mobilization (Anterior to Posterior Femur on Tibia Mobilization). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vb_FRyydYyI

- ↑ CPM Machine in Use. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLvJwe5GAfg

- ↑ Knee Capsular Stretch. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcYDCDbsh3s

- ↑ Restoring Knee Screw Home Mechanism. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uNWkHPcpDfY

- ↑ Treat Knee Cap Pain (Patellar Mobilization Technique). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGVbR1EiJzs

- ↑ Hart JM, Pietrosimone B, Hertel J, Ingersoll CD. Quadriceps activation following knee injuries: a systematic review. Journal of athletic training. 2010 Jan;45(1):87-97.

- ↑ Suter E, McMorland G, Herzog W, Bray R. Decrease in quadriceps inhibition after sacroiliac joint manipulation in patients with anterior knee pain. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 1999 Mar 1;22(3):149-53.

- ↑ Suter E, McMorland G, Herzog W, Bray R. Conservative lower back treatment reduces inhibition in knee-extensor muscles: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2000 Feb 1;23(2):76-80.

- ↑ Palmieri-Smith RM, Leonard-Frye JL, Garrison CJ, Weltman A, Ingersoll CD. Peripheral joint cooling increases spinal reflex excitability and serum norepinephrine. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2007 Jan 1;117(2):229-42.

- ↑ Hopkins JT, Ingersoll CD, Edwards J, Klootwyk TE. Cryotherapy and transcutaneous electric neuromuscular stimulation decrease arthrogenic muscle inhibition of the vastus medialis after knee joint effusion. Journal of athletic training. 2002 Jan;37(1):25.

- ↑ Stevens JE, Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler L. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for quadriceps muscle strengthening after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a case series. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2004 Jan;34(1):21-9.