Q Angle

Original Editor - Venus Pagare

Top Contributors - Venus Pagare, Andeela Hafeez, Abdallah Ahmed Mohamed, Sehriban Ozmen, Ehtisham Panhwar, Laura Ritchie, Ben Kasehagen, WikiSysop, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Admin, Kim Jackson, Claire Knott, Wanda van Niekerk, Evan Thomas and George Prudden

Background[edit | edit source]

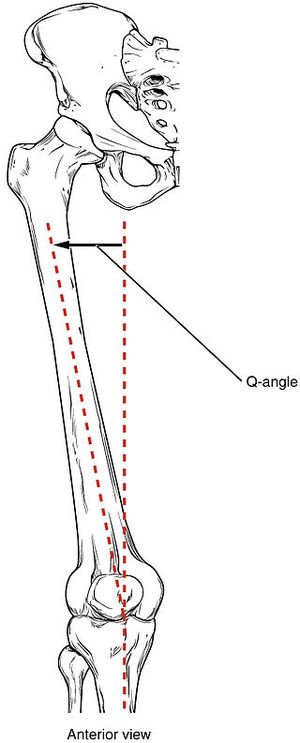

The direction and magnitude of force produced by the quadriceps muscle has great influence on patellofemoral joint biomechanics. The line of force exerted by the quadriceps is lateral to the joint line mainly due to the large cross-sectional area and force potential of the vastus lateralis. Since there exists an association between patellofemoral pathology and excessive lateral tracking of the patella, assessing the overall lateral line of pull of the quadriceps relative to the patella is a meaningful clinical measure. Such a measure is referred to as the Quadriceps angle or Q angle.

Measurement[edit | edit source]

The Q angle is formed between:

- A line representing the resultant line of force of the quadriceps, made by connecting a point near the ASIS to the mid-point of the Patella.

- The Q angle can be measured in laying or standing.(1) Standing is usually more suitable, due to the normal weight-bearing forces being applied to the knee joint as occurs during daily activity.[1]

- Traditionally, the Q angle has been measured with the knee at or near full extension (but not hyperextension) with subjects in supine and the quadriceps relaxed, as lateral forces on the patella may be more of a problem in these circumstances.

- With (2)the knee flexed, the patella is set within the intercondylar notch, and even a very large lateral force on the patella is unlikely to result in dislocation. Furthermore, the Q angle will reduce with knee flexion as the tibia rotates medially in relation to the femur.[1]

- This is regarded as the 'traditional' or 'conventional' method. The Q angle has also been assessed in standing.

asd

Normative Values [edit | edit source]

- In women, the Q angle should be less than 22 degrees with the knee in extension and less than 9 degrees with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. In men, the Q angle should be less than 18 degrees with the knee in extension and less than 8 degrees with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. A typical Q angle is 12 degrees for men and 17 degrees for women.[2]

Measuring Q Angle[edit | edit source]

Position: Patient supine with knee extended. The therapist stands next to patient.

Application: When measuring ensure that the lower extremity is at a right angle to the line joining each ASIS. The foot should be placed in a neutral position relative to supination and pronation with the hip in neutral position relative to medial and lateral rotation. Draw a line from ASIS to the midpoint of patella and then from the midpoint of the patella to the tibial tubercle. The resultant angle formed by the crossing of these two lines is called the Q angle.

Positive sign: Normal Q angle score for females is between 13-18° with values greater than and lesser considered abnormal and may indicate the patient is at risk of developing chondromalacia patellae, patella alta or mal-tracking of the patella.

| [3] |

Problems with Measuring 'Q' Angle[edit | edit source]

- A Problem with using the Q angle as a measure of the lateral pull on the patella is that the line between the ASIS and the mid-patella is only an estimate of the line of pull of the quadriceps and does not necessarily reflect the actual line of pull in the patient being examined.

- If a substantial imbalance exists between the vastus medialis and vastus lateralis muscles in a patient, the Q angle may lead to an incorrect estimate of the lateral force on the patella because the actual pull of the quadriceps muscle is no longer along the estimated line.

- Furthermore, a patella that sits in an abnormal lateral position in the femoral sulcus because of imbalanced forces, will yield a smaller Q angle because the patella lies more in line with the ASIS and tibial tuberosity.[4]

Factors affecting 'Q' Angle[edit | edit source]

Increase in Q angle is associated with[5]:

- Femoral anteversion

- External tibial torsion

- Laterally displaced tibial tubercle

- Genu valgum: increases the obliquity of the femur and concomitantly, the obliquity of the pull of the quadriceps

Clinical Importance[edit | edit source]

- An understanding of the normal anatomical and biomechanical features of the patellofemoral joint is essential to any evaluation of knee function. The Q angle formed by the vector for the combined pull of the quadriceps femoris muscle and the patellar tendon, is important because of the lateral pull it exerts on the patella.[6]

- Any alteration in alignment that increases the Q angle is thought to increase the lateral force on the patella.

- This can be harmful because an increase in this lateral force may increase the compression of the lateral patella on the lateral lip of the femoral sulcus.

- In the presence of a large enough lateral force, the patella may actually sublux or dislocate over the femoral sulcus when the quadriceps muscle is activated on an extended knee.[1]

- It has also been suggested that an abnormal Q angle may also influence neuromuscular responses and quadriceps reflex response time.

Abnormal Value(Pathology)[edit | edit source]

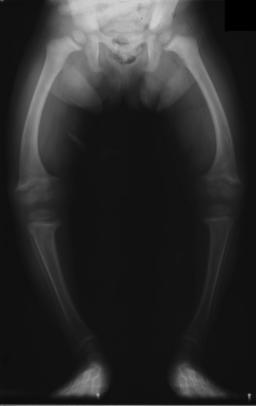

- Excessive Genu Valgum

Commonly called Knock Knee, is a condition in which the knees angle in and touch each other when the legs are straightened. Individuals with severe valgus deformities are typically unable to touch their feet together while simultaneously straightening the legs.Several factors can lead to excessive genu valgum, or knock knee . These include previous injury, genetic predisposition, high body mass index, and laxity of ligaments. Genu valgum may also result from or be exacerbated by abnormal alignment or muscle weakness at either end of the lower extremity., coxa vara (i.e., a femoral neck-shaft angle less than 125 degrees) or weakened hip muscles (such as the gluteus medius) can, at least increase the valgus load on the knee. In some cases excessive foot pronation may increase the valgus load on the knee by allowing the distal end of the tibia to abduct farther away from the mid line of the body. Over time, the tensional stress placed on the MCL and adjacent capsule may weaken the tissue., excessive valgus of the knee may negatively affect patellofemoral joint tracking and create additional stress on the ACL. Standing with a valgus deformity of approximately 10 degrees greater than normal directs most of the joint compression force to the lateral joint compartment.[7] This increased regional stress may lead to lateral uni compartmental osteoarthritis. Knee replacement surgery may be indicated to correct a valgus deformity, especially if it is progressive, is painful, or causes loss of function.

- Genu varum and Genu Recuravatum

Full extension with slight external rotation is the knee’s close packed, most stable position. The knee may be extended beyond neutral an additional 5 to 10 degrees, although this is highly variable among persons. Standing with the knee in full extension usually directs the line of gravity from body weight slightly anterior to the medial-lateral axis of rotation at the knee. Gravity, therefore, produces a slight knee extension torque that can naturally assist with locking of the knee, allowing the quadriceps to relax intermittently during standing. Normally this gravity-assisted extension torque is resisted primarily by passive tension in the stretched posterior capsule and stretched flexor muscles of the knee, including the gastrocnemius. Hyperextension beyond 10 degrees of neutral is frequently called genu recurvatum. Mild cases of recurvatum may occur in otherwise healthy persons, often because of generalized laxity of the posterior structures of the knee. The primary cause of more severe genu recurvatum is a chronic, overpowering (net) knee extensor torque that eventually overstretches the posterior structures of the knee. The overpowering knee extension torque may stem from poor postural control or from neuromuscular disease that causes spasticity of the quadriceps muscles and/or paralysis of the knee flexors.[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Levangie, P.K. and Norkin, . Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis. (2005)

- ↑ Mohammad-Jafar Emami, Mohammad-Hossein Ghahramani, Farzad Abdinejad and Hamid Namazi . "Q-angle: an invaluable parameter for evaluation of anterior knee pain"(January 2007)

- ↑ Tsudpt11's channel. Q angle. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vEsoXQ8kHwQ [last accessed 11/09/14]

- ↑ Buckup K.Clinical test for musculoskeletal system. 2006

- ↑ Singh AP. Q Angle Measurement and Significance. https://boneandspine.com/q-angle/ (last accessed 12 June 2019)

- ↑ Horton MG, Hall TL. Quadriceps Femoris Muscle Angle:Normal Values and Relationships with Gender and Selected Skeletal Measures. 1989

- ↑ Johnson F, Leitl S, Waugh W: The distribution of load across the knee. A comparison of static and dynamic measurements,1980

- ↑ Benson, Michael; Fixsen, John; Macnicol, Malcolm. Children's Orthopaedics and Fracture(1 August 2009)