Paediatric ACL Injuries

Original Editor - Wanda van Niekerk

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Over the past few years there has been a rise in paediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries.[2][3] This is of great concern to clinicians seeing and treating these patients. Various questions arise when faced with a paediatric ACL injury, such as: Do children with ACL injuries mature similarly as their uninjured peers?[4] Should they continue with sport or rather focus on their education and other interests?[4] Is an ACL rupture a life changing event for these children?[4] Children with ACL injuries face an array of challenges, such as having to cope with their knee problem for the rest of their life, and this in turn may compromise their quality of life.[4] Furthermore, it may increase their risk of further injury, as well as the risk for meniscal tears and early onset osteoarthritis.[5] Adding to all these issues, is the limited high-quality evidence available to guide decision-making in the treatment of paediatric ACL injuries.[6]

Children are a vulnerable population and clinicians in contact with this population has the responsibility to provide accurate information as well as effective treatment. The long-term prognosis after an ACL injury in childhood is still uncertain and there is a need for evidence-based studies to aid and strengthen confidence in clinical decision-making.[4] It is important to note that "long-term outcomes after ACL injury in childhood, including the development of osteoarthritis, have not been studied."[4]

In the current scope of clinical uncertainty and the limited evidence-based scientific knowledge, it is therefor challenging to manage these type of injuries in children. Other compounding factors are the intricacies involved in shared decision-making with children and the potential long-term and life-changing effect of such injuries.[4]

Prevention of Paediatric ACL Injuries[edit | edit source]

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in childhood has serious potential long-term consequences[4] as well as an increased risk of re-injury to either knee.[7] It is therefore essential to prevent ACL injuries in children as well as incorporate the principles of injury prevention into the treatment of the child with an ACL injury.[4]

Research has shown great advances in the development and application of ACL injury prevention programs, specifically in pivoting sports such as football.[8] A reduction in the number of athletes sustaining an primary ACL injury and a reduction in the number of new ACL injuries among athletes who return to sport after primary ACL injury, have been reported.[9][10]

A modifiable risk factor for injury is the athlete's biomechanical movement patterns[4]. These biomechanical movement patterns are targeted by specific Injury Prevention Programs (IPP). These injury prevention programs aim to incorporate strength training, plyometrics as well as sport-specific agility training.[11] Another key component of the programs is the education of the coach and athlete, specifically on cutting and landing techniques (eg, wide foot position when cutting or flexed knee when landing). These specific methods avoid high-risk knee positions and are fundamental in the aim to prevent paediatric ACL injuries.

Advantages of Injury Prevention Programs[edit | edit source]

- straightforward to implement[4]

- require little or no equipment[4]

- can be performed as part of regular team training or physical education 2-3 times per week[4]

It is advised that children be introduced to injury prevention programs at an early age or developmental process. This provides the child with the best opportunity to develop and maintain strong and favorable movement strategies.[4]

The FIFA+ is an injury prevention program that reduces football-related lower limb injuries by over 50%.[12][13][14] Children who take part and complete these programs show improved motor control as well as an improvement in balance and agility, when compared with children not completing the program.[14]

Although these injury prevention programs have successful outcomes such as a reduced injury rate and injury time loss,[12][15] the effect thereof can be influenced by how frequent athletes perform the training.[16][17] For these injury prevention programs to be successful it needs to be consistently implemented and utilised, as well as adhered to across all levels of competitive play.[4] These factors are the biggest challenges that clinicians face. It is also paramount that clinicians involved in youth sports and treating paediatric athletes with ACL injuries, advocate strongly for injury prevention methods in all settings.[4]

Diagnosis of Paediatric ACL Injuries[edit | edit source]

As mentioned before, injury prevention programs are the first line of defense against the possible effects of an ACL injury. Should these prevention strategies fail, it is incumbent that a timely and accurate diagnosis be made.[4] Accurate diagnosis is the starting point for effective management planning as well as shared decision-making.[4] Clinicians make use of their specific skills and gather knowledge from:

- patient history

- examination

- clinical tests

- imaging

With this combined information clinicians can build a clear clinical picture that will enable diagnosis and assist in the treatment plan.[4]

Clinical pearls to consider with the diagnosis of paediatric ACL injuries[edit | edit source]

- Haemarthrosis (acute swelling in the knee within 24 hours after trauma due to intra-articular bleeding) following an acute knee injury is suggestive of a structural knee injury.[4]

- Diagnosis is more challenging with children, as they may be poor historians, have greater physiological joint laxity (examine both knees!) and MRI interpretation is difficult as a result of developmental variants in children.[18]

- Children have an immature skeleton and this predisposes them to different knee injuries (e.g. sleeve fracture of patella, epiphysiolysis) than adults.[4]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

Key points with regards to imaging

- Consider starting assessment with plain knee radiographs for all paediatric patients with a haemarthrosis or suspected structural knee injury

- Tibial eminence fractures and ACL tear may have similar history and clinical examination findings

- Vital to rule out any other possible paediatric fractures such as sleeve fracture of the patella or an epiphyseal fracture

- MRI can be performed to confirm diagnosis of an ACL injury and to evaluate other soft tissue structures[19]

- MRI may show other relevant injuries such as meniscal tears, osteochondral lesions and other ligament injury

- In paediatric patients presenting with a locked knee, MRI is needed to assess the possibility of a displaced bucket handle meniscal tear or an osteochondral lesion

Special tests[edit | edit source]

- Lachman test

- Anterior Drawer Test of the Knee

- Pivot shift test

- Slocum test

- Lateral pivot shift for anterolateral stability

Clinicians should be aware that "no isolated question, test or image can accurately identify an ACL injury, every time."[4]

Management of Paediatric ACL Injuries[edit | edit source]

It is important for clinicians to be familiar with the available treatment options for children with ACL injuries. The various options should be discussed with the child and the child's parents/guardian in order to facilitate and enable a the process of shared decision-making on how to manage the knee injury.[4]

Treatment goals[edit | edit source]

- Restore a stable, well-functioning knee that allows a healthy, active lifestyle across the lifespan

- Reduce the impact of existing and the risk of further meniscal or chondral pathology, degenerative joint changes and the need for future surgical intervention

- Minimise the risk of growth arrest and femur and tibia deformity

Treatment options[edit | edit source]

- High-quality rehabilitation alone (non-surgical treatment)

- ACL reconstruction plus high-quality rehabilitation

High-quality rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation is essential in the management of ACL injuries. The principles of rehabilitation stay the same, whether the child has had surgery or has selected non-surgical treatment. It remains uncertain whether adult principles apply to children.[20] "Children are not small adults!"[4] Therefore, rehabilitation exercises and functional goals should be modified and not just copied from adult-orientated rehabilitation protocols.[4] One cannot expect children to perform rehabilitation exercises with immaculate technique under no supervision! Qualified experienced clinicians should supervise rehabilitation for the child with an ACL injury. Furthermore, rehabilitation must be performed in close collaboration with the child's parents/guardian.[4]

Rehabilitation focus[edit | edit source]

Dynamic, multijoint neuromuscular control is the most important area to focus on. In young patients with an open physis and younger than 12 years, less importance is placed on muscular strength development and hypertrophy. Later on during maturation, and through the onset of puberty, rehabilitation protocols more resembling of the adult-orientated protocols are appropriate and can be implemented. These protocols can include heavier and externally loaded strength training.[4]

- Rehabilitation must be thorough

- Rehabilitation must be individualised to the child's physiological and psychological maturity

- Focus on exercises that facilitate dynamic lower limb alignment

- Focus on biomechanically sound movement patterns

- Gradual progression through phases II and III of the paediatric ACL rehabilitation protocol

- Be aware of re-injury anxiety as well as the child's confidence in his/her injured knee

- After surgery, ensure that the rehabilitation program is adapted accordingly

- Design rehabilitation programs that allows the child to participate in his/her team training sessions to maintain the social benefits of being part of a team

- Parents or guardians should be actively involved in rehabilitation on a daily basis

Rehabilitation phases[edit | edit source]

Ardern et al[4] advocate that the rehabilitation for the child with an ACL injury be divided into four phases. There is an additional prehabilitation phase for children undergoing surgery. It is of the utmost importance that specific clinical and functional goals be reached before progressing to the next phase of rehabilitation. Children should avoid any cutting and pivoting actions during their sport, free play and physical education classes during phases I and II.

| Recommended functional tests and return to sport criteria for the child and adolescent with ACL injury (From:2018 International Olympic Committee consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of paediatric anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries)[4] |

| For patients who choose ACL reconstruction

Prehabilitation

|

| For patients who choose ACL reconstruction OR non-surgical treatment

Phase I to phase II

Phase II to phase III

Phase III to phase IV: sport participation (return to sport criteria), and continued injury prevention

Muscle strength testing should be performed using isokinetic dynamometry or handheld dynamometry/one repetition maximum. The type of test and experience of the tester are highly likely to influence the results. If using handheld dynamometry/one repetition maximum, consider increasing the limb symmetry criterion cut-off by 10% (ie, 90% limb symmetry becomes 100% limb symmetry). Clinicians who do not have access to appropriate strength assessment equipment should consider referring the patient elsewhere for strength evaluation |

Exercise examples for each phase of paediatric ACL rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Phase I[edit | edit source]

Other exercise examples for phase I:[edit | edit source]

- Quads setting

- Closed chain hip and pelvis control exercises

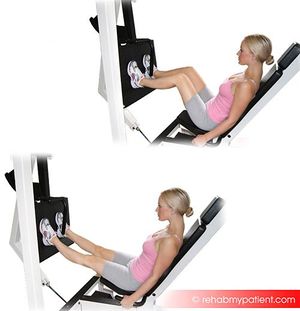

Phase II[edit | edit source]

Other examples of exercises for Phase II;[edit | edit source]

- Step-ups (front and lateral)

- Single leg standing control of dynamic terminal knee extension

Phase III[edit | edit source]

Other exercise samples for Phase III;[edit | edit source]

- Stair jumps

- Hopping and landing

- Agility exercises

- Running direction change exercises

PHASE IV[edit | edit source]

- Injury prevention programs such as FIFA 11+

Rehabilitation progression[edit | edit source]

Whether the child is undergoing an ACL reconstruction or opting for non-surgical treatment, the progression through the functional milestones are similar. There are different expectations for progression and return to sport, though. Full return to sport is dependent on the child managing to successfully achieve the return to sports criteria[21]

Guidelines for time to return to sport[edit | edit source]

- Non-surgical - treatment should last for at least 3 - 6 months[22]

- Surgery - post-operative treatment should last for a minimum of 9 months[23]

- Use the rehabilitation period and train the uninjured leg as well as there is a risk of contralateral injury[24]

- Once the child is back at sport, a detailed and sport specific injury prevention program should be part of usual training.

Considerations when designing rehabilitation programs for young children[4][edit | edit source]

- Avoid boredom - design a home-based program with emphasis on play and a variation of exercises

- Be wise about what tests to use - tests like single-leg hop and isokinetic strength tests have large measurement errors in young children[25]

- Concentrate on the quality of movement instead of symmetry in tests like single-leg hop

- Be a responsible clinician - movement quality tests still needs validation - make sure that you have the skill and experience to use these tests, if not....refer!

- Current return to sport criteria is designed and tested in skeletally mature athletes, it is still unsure if the same criteria can be used in the prepubescent child.

See also:

ACL Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation Planning

ACL Rehabilitation: Re-injury and Return to Sport Tests

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Child Health Questionnaire

- PedsQL

- Paediatric PROMIS

- Pedi - IKDC

- KOOS - Child

- Paediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale

Ethical Considerations[edit | edit source]

The fundamental question is: "What are the clinician's role and responsibilities?"[4] Clinical decision-making involving children is difficult and furthermore challenged by limited scientific knowledge.[4] Although it is impossible to provide specific ethical guidelines applicable to all paediatric and adolescent sporting injuries, it is undeniable that it is in the best interest of all children not to have knee and associated injuries.[4]

Injury prevention programs are key to managing the best interests of the child and clinicians should support and encourage policies and practices that prioritise injury prevention. The primary focus for clinicians however should be to protect the integrity of the knee at all times. Decisions on how to achieve this should be shared between the clinician, the child and the parent or guardian.[4] Clinicians need to act in the best interest of the child in the process of shared decision-making, while parents give consent.[4] Furthermore, it is important for the clinician to always obtain the consent of the child, irrespective of the parents/guardians wishes, at a communication level that matches the child's competence.[4] The child should always be present in discussions concerning him or her, to respect the child's autonomy.[4] Consensus should be reached between all parties when decisions are made and based on realistic assessments of risks and benefits. It is the responsibility of the clinician to guide these discussions and provide accurate information obtained from the best quality research.[4]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM). Paediatric anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MM6UY1MpqAE. Published on 13 April 2019. (last accessed 31 March 2020)

- ↑ Werner BC, Yang S, Looney AM, Gwathmey FW Jr. Trends in Pediatric and Adolescent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury and Reconstruction. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36(5):447-52.

- ↑ Shaw L, Finch CF. Trends in Pediatric and Adolescent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Victoria, Australia 2005-2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jun 5;14(6). pii: E599.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 4.36 4.37 4.38 Ardern CL, Ekås G, Grindem H, Moksnes H, Anderson AF, Chotel F, Cohen M, Forssblad M, Ganley TJ, Feller JA, Karlsson J, Kocher MS, LaPrade RF, McNamee M, Mandelbaum B, Micheli L, Mohtadi NGH, Reider B, Roe JP, Seil R, Siebold R, Silvers-Granelli HJ, Soligard T, Witvrouw E, Engebretsen L. 2018 International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Pediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 Mar 21;6(3):2325967118759953

- ↑ Whittaker JL, Woodhouse LJ, Nettel-Aguirre A, Emery CA. Outcomes associated with early post-traumatic osteoarthritis and other negative health consequences 3-10 years following knee joint injury in youth sport. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 Jul;23(7):1122-9.

- ↑ Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. The current evidence for treatment of ACL injuries in children is low: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012 Jun 20;94(12):1112-9.

- ↑ Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of Second ACL Injuries 2 Years After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014 Jul;42(7):1567-73.

- ↑ Waldén M, Atroshi I, Magnusson H, Wagner P, Hägglund M. Prevention of acute knee injuries in adolescent female football players: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012 May 3;344:e3042.

- ↑ Soligard T, Myklebust G, Steffen K, Holme I, Silvers H, Bizzini M, Junge A, Dvorak J, Bahr R, Andersen TE. Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008 Dec 9;337:a2469.

- ↑ Silvers-Granelli H, Mandelbaum B, Adeniji O, Insler S, Bizzini M, Pohlig R, Junge A, Snyder-Mackler L, Dvorak J. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program in the Collegiate Male Soccer Player. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Nov;43(11):2628-37.

- ↑ Emery CA, Roy TO, Whittaker JL, Nettel-Aguirre A, van Mechelen W. Neuromuscular training injury prevention strategies in youth sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Jul;49(13):865-70.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Thorborg K, Krommes KK, Esteve E, Clausen MB, Bartels EM, Rathleff MS. Effect of specific exercise-based football injury prevention programmes on the overall injury rate in football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the FIFA 11 and 11+ programmes. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Apr;51(7):562-571.

- ↑ Rössler R, Junge A, Bizzini M, Verhagen E, Chomiak J, Aus der Fünten K, Meyer T, Dvorak J, Lichtenstein E, Beaudouin F, Faude O. A Multinational Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial to Assess the Efficacy of '11+ Kids': A Warm-Up Programme to Prevent Injuries in Children's Football. Sports Med. 2018 Jun;48(6):1493-1504.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rössler R, Donath L, Bizzini M, Faude O. A new injury prevention programme for children's football--FIFA 11+ Kids--can improve motor performance: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(6):549-56.

- ↑ Attwood MJ, Roberts SP, Trewartha G, England ME3, Stokes KA. Efficacy of a movement control injury prevention programme in adult men's community rugby union: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Mar;52(6):368-374.

- ↑ Hägglund M1, Atroshi I, Wagner P, Waldén M. Superior compliance with a neuromuscular training programme is associated with fewer ACL injuries and fewer acute knee injuries in female adolescent football players: secondary analysis of an RCT. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Oct;47(15):974-9.

- ↑ Soligard T1, Nilstad A, Steffen K, Myklebust G, Holme I, Dvorak J, Bahr R, Andersen TE. Compliance with a comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in youth football. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Sep;44(11):787-93.

- ↑ Thapa MM1, Chaturvedi A, Iyer RS, Darling SE, Khanna PC, Ishak G, Chew FS. MRI of pediatric patients: Part 2, normal variants and abnormalities of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012 May;198(5):W456-65.

- ↑ Kocher MS, DiCanzio J, Zurakowski D, Micheli LJ. Diagnostic performance of clinical examination and selective magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of intraarticular knee disorders in children and adolescents. (abstract only) Am J Sports Med. 2001 May-Jun;29(3):292-6.

- ↑ Yellin JL, Fabricant PD, Gornitzky A, Greenberg EM, Conrad S, Dyke JA, Ganley TJ. Rehabilitation Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears in Children: A Systematic Review. JBJS Rev. 2016 Jan 19;4(1). pii: 01874474-201601000-00004.

- ↑ Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, Witvrouw E, Clarsen B, Cools A, Gojanovic B, Griffin S, Khan KM, Moksnes H, Mutch SA, Phillips N, Reurink G, Sadler R, Silbernagel KG, Thorborg K, Wangensteen A, Wilk KE, Bizzini M. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;50(14):853-64.

- ↑ Grindem H, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Nonsurgical or Surgical Treatment of ACL Injuries: Knee Function, Sports Participation, and Knee Reinjury: The Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohort Study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Aug 6;96(15):1233-1241.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;50(13):804-8.

- ↑ Dekker TJ, Godin JA, Dale KM, Garrett WE, Taylor DC, Riboh JC. Return to Sport After Pediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Its Effect on Subsequent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 Jun 7;99(11):897-904

- ↑ Johnsen MB, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Risberg MA. Inter- and intrarater reliability of four single-legged hop tests and isokinetic muscle torque measurements in children. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015 Jul;23(7):1907-16.