Neck and Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders

Introduction:[edit | edit source]

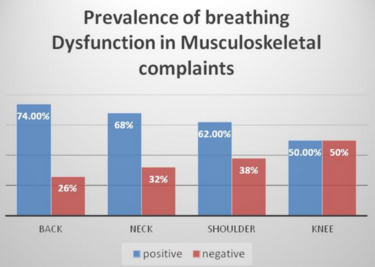

A dysfunctional breathing pattern is defined as when the "normal biomechanical pattern of breathing is disrupted, resulting in dyspnoea and associated non-respiratory symptoms that cannot be fully explained by disease pathophysiology" (Ionescu et al, 2021). Normal breathing involves synchronised upper and lower rib cage movement as well as activation of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles (Kaminoff, 2006). Abnormal breathing, also known as thoracic breathing” instead involves breathing from the upper chest with greater upper rib cage motion compared to lower rib cage (Chaitow et al, 2002). Thoracic breathing is produced by recruiting the accessory muscles of respiration (including upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles) rather than abdominal motion. A cross-sectional study by Deshmukh et al (2022) found that 74% of participants complaining of back pain and 68% of those complaining of neck pain presented with a dysfunctional breathing pattern. Individuals with poor posture (Lewitt, 1980), scapular dyskinesis (Clifton-Smith & Rowley, 2011), low back pain (LBP) and neck pain have also been shown to exhibit faulty breathing mechanics.

There is evidence suggesting a relationship between lower back pain and respiration. The diaphragm is a key driver of the respiratory pump and attaches onto the lower six ribs, xiphoid process and the lumbar vertebral column. Hodges et al (2007) stated that as the diaphragm has an important role in both postural and breathing functions, disruption in one could negatively affect the other. Recent studies have found individuals with LBP have a higher diaphragm position and compensate by increasing their tidal volume during lifting and lower tasks to provide adequate pressure support (Hagins & Lambert, 2011). As well as a greater prevalence of diaphragm fatigue compared to healthy controls (Janssens et al, 2013). A systematic review (Beeckmans et al, 2016) found a significant correlation between lower back pain and dysfunctional breathing including both pulmonary pathology and non-specific breathing pattern disorders. Furthermore, a case-control study (Roussel et al, 2009) observing patients with chronic LBP found significantly more altered breathing patterns during performance of motor testing.

Spinal stability and respiration use similar muscles to function and there is a need for a stabilised cervical and thoracic spine to assist movement of the ribs during inspiration and expiration. The diaphragm contributes to postural control by increasing intra-abdominal pressure (Hodges et al, 2000). Spinal instability could cause mechanical alterations leading to insufficient respiratory function and the activation of accessory muscles, producing a dysfunctional breathing pattern. A systematic review (Kahlaee, Ghamkhar and Arab, 2017) including 68 studies found a significantly lower maximum inspiration and expiration pressures in patients with chronic neck pain compared to asymptomatic patients. Muscle strength and endurance, cervical range of motion and lower Pco2 were found to be significantly correlated to reduced chest expansion and neck pain. The study concluded breathing re-education to be effective in improving come cervical musculoskeletal impairment and breathing pattern disorders.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The thoracic cage is inclusive of the spine, ribs, and the adjacent muscles. The anatomy at this area is important to ensure effective inspiration and expiration in the functional breathing process. Primary inspiratory muscles are the diaphragm and external intercostals, to help elevate the ribs and sternum, with a ‘bucket handle’ rib motion. Expiration is usually a passive process, with additional muscles such as the internal intercostals, and abdominal muscles, making this forceful if required.

The muscles of the diaphragm are directly connected to the spine, via the lower six ribs and their costal cartilage, upper three lumbar vertebrae as right crus, and upper two lumbar vertebrae as left crus, separating the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. The intercostal muscles are located between ribs to aid expansion of the thoracic cage on inspiration.

Accessory muscles aid these original breathing mechanics when additional power is needed to generate larger, deeper breaths. These often include the sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, and trapezius, however any muscle attached to the upper limb and thoracic cage can act as an accessory muscle for inspiration (Physiopedia a, n.d.).

What Defines Neck and Low Back Pain?[edit | edit source]

The neck is prone to overuse and injury due to having the most range of movement and can be acute or chronic. Pain may worsen with certain activities and may reduce Range of Movement (ROM) or impact activities of daily living (ADLs). Non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) is defined as pain not attributable to a diagnosis or pathology (eg infection, stenosis) with 84% of the UK population experiencing NSLBP. Those receiving care and those not experiencing similar outcomes, and 11-12% of the global population are estimated to experience disabling chronic low back pain (Balague et al, 2012).

Acute: Occurs suddenly and heals quickly. Typically non-serious and due to muscular sources.

Chronic: Persistent Pain greater than three months, staying consistent or worsening. This can be due to a more serious condition such as degeneration or injury.

Signs and Symptoms Commonly Experienced in Neck and LBP

· Stiffness

· Tightness

· Aching

· Burning

· Stabbing

· Shooting Pains

· Radicular Pains (including pins and needles)

Other symptoms associated with neck pain include headaches, muscle contraction or spasms (typical after whiplash) or face symptoms including tension or numbness. Stress is a yellow flag that may also contribute to pain felt in the neck and low back through catastrophising and certain beliefs of pain.

Red Flag symptoms of Neck and Back Pain include:

· Worsening pain not resolving

· Unremitting night pain

· Unexpected weight loss

· Changes to bladder and bowels

· Saddle anaesthesia

· Gait (walking pattern) changes

· Recent trauma

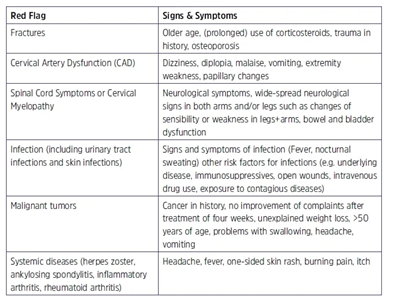

Red flags are signs and symptoms that may indicate a more serious condition that would contraindicate therapy or need immediate treatment and rule out sinister pathologies (NHS Pathways, 2019).

Clinical Indication Of Dysfunctional Breathing[edit | edit source]

About 6-12% of people experience breathing dysfunction with chronic symptoms developing subtly over time (University Hospital Southampton, 2023). Dysfunctional breathing is associated with morbidity and increased health-related costs during management. It is commonly misdiagnosed due to the similarity of symptoms compared to other conditions such as dyspnoea and a potential lack of awareness and understanding of the condition.

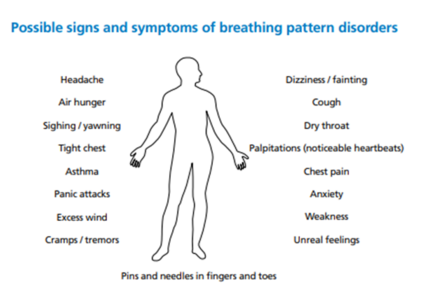

Common symptoms found clinically may include:

· Mouth breathing

· Tension in shoulders or neck

· Neck/shoulder pain

· Hyperventilation

· Breathlessness

· Persistent coughing

· Excessive yawning or sighing

· Air hunger

A mixture of these symptoms and not being able to get a full breath can have confounding results of dizziness, poor concentration, pins and needles and fatigue.(University Hospital Southampton, 2023) (Kent Community Health, 2022)

Red Flag Symptoms

Breathing dysfunction signs and symptoms are associated with other more serious conditions that may require further medical treatment and may include:

· Chest pains

· Palpitations

· Breathlessness

Dysfunctional breathing causes or triggers are not always associated with a lung problem and can occur suddenly. Some causes include:

· Stress

· Anxiety

· COPD/Asthma

· Traumatic event

· Pain in the abdomen

· Digestive issues

(Kent Community Health, 2022)

Differential diagnoses[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorder

| Cardiac causes: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute pulmonary oedema | |||

| Cardiac arrhythmia | |||

| Cardiac tamponade | |||

| Chronic heart failure | |||

| Silent myocardial infarction | |||

| Superior vena cava syndrome | |||

| Pulmonary causes: | |||

| Asthma | |||

| Bronchiectasis/COPD/ILD | |||

| Covid-19 infection | |||

| Lung/lobar collapse | |||

| Pleural effusion | |||

| Pneumonia | |||

| Pneumothorax | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | |||

| Lung/pleural cancer | |||

| Other: | |||

| Anaemia | |||

| Anaphylaxis | |||

| Anxiety related breathlessness | |||

| Diaphragmatic splinting | |||

| (NICE b, 2022) |

Neck pain (cervical spine)

| Neck Pain without radiculopathy | Neck pain with radiculopathy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific neck pain | Abscess | ||

| Acute disc prolapse | Anterior interosseous nerve entrapment | ||

| Acute torticollis | Arteriovenous malformation | ||

| Acute trauma (e.g. Whiplash) | Carpal tunnel syndrome | ||

| Adverse drug reactions | Cubital tunnel syndrome | ||

| Osteoarthritis of the cervical spine | Herpes zoster | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | Parsonage-Turner syndrome (brachial plexopathy) | ||

| Cervical strain | Posterior interosseus nerve entrapment | ||

| Cervical fracture or dislocation | Radial tunnel syndrome | ||

| Cervical radiculopathy | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy | ||

| Fibromyalgia | Rotator cuff tendinosis | ||

| Infection | Thoracic outlet syndrome | ||

| Malignancy | |||

| Carotid or vertebral artery dissection | |||

| Neurological disorders leading to dystonia | |||

| Psychogenic dystonia | |||

| (NICE e, 2023) | (NICE b, 2023) |

Thoracic spine pain

| Thoracic pain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Costochondritis | |||

| Lower rib pain syndrome | |||

| Sternalis syndrome | |||

| Thoracic costovertebral joint dysfunction | |||

| Fibromyalgia | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |||

| Axial spondyloarthropathy | |||

| Psoriatic arthritis | |||

| Osteoporotic fracture | |||

| Neoplasm with pathological fracture or bone pain | |||

| (Winzenburg et al, 2005 as cited at Physiotutors.com b, no date) |

Lower back pain (lumbar spine)

| Lower back pain without radiculopathy | Lower back pain with radiculopathy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological: | metastatic neoplasm | ||

| Sciatica | Acute cholecystitis | ||

| Myelopathy or a higher cord lesion | Cardiac or pulmonary disease | ||

| Peroneal palsy or other neuropathies | Pancreatitis | ||

| Deep gluteal syndrome/Piriformis syndrome | Pelvic inflammatory disease | ||

| Spinal stenosis | Pelvic mass | ||

| Systemic: | Prostatitis | ||

| Sacroiliitis in spondyloarthropathies | Pyelonephritis | ||

| Vascular claudication | |||

| Other: | |||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | |||

| Aseptic necrosis of femoral head | |||

| Facet joint arthropathy | |||

| Greater trochanteric pain | |||

| Intra-abdominal pathology | |||

| Osteoarthritis of the spine or hip | |||

| Osteoporosis | |||

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |||

| Shingles (Herpes zoster) | |||

| (NICE a, 2022) | (NICE c, 2022) |

Low Back Pain Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

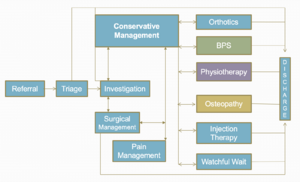

Triage[edit | edit source]

Triaging patients is vital to ensure the appropriate management strategy is selected. Decision-making and problem solving needs to occur, following an initial assessment which identifies the patient’s pain pattern, to then categorise the correct treatment for each individual patient (Hall, 2014). Discussed above are the Red Flags and conditions that you need to be aware of during this stage, as safety is of paramount importance.

The Patient's Perspective[edit | edit source]

As the clinician you may choose to ask an open question regarding the patient’s understanding about why they may be attending the appointment today, to listen actively to the patient’s story, and noticing evidence and reasoning for physical illness and emotional distress (Gask and Usherwood, 2002). This can address the dual focus where patients usually have a combination of both and are not exclusively physically ill.

It also gives the patient an opportunity to consider their understanding, feelings, coping strategies, attitude to physical activity, beliefs, expectations, and goals regarding their experience with their pain (Jones and Rivett, 2004). The clinician can then start to consider appropriate management strategies to support these perspectives using collaborative clinical reasoning and inform these beliefs using education techniques.

The use of open questions should be predominantly used to ensure these collaborative goals are met, as the clinician can appropriately identify where education may be required (Petty, 2018). If the clinician picks up on any information that may not be realistic or helpful, this can be addressed at a later stage with the patient.

Social History[edit | edit source]

It is important to ask the patient about their employment status, home situation, and any leisure activities the patient enjoys, to know their responsibilities and what they need to be able to achieve on a functional level, for goal setting to be appropriate.

Body Chart and Pain Recognition[edit | edit source]

This is a method often used to help highlight the exact area and type of symptoms being experienced by the patient. This can help focus questioning and pattern recognition in relation to diagnoses (Petty, 2018). You can mark each area to distinguish symptoms differently, but also how they may link together. The quality of the pain can also be determined here, including encouraging the patient to ‘describe the pain’ to provide an insight into the physiological mechanism.

This can help determine whether the pain is of nociceptive, peripheral neuropathic, central sensitisation, or autonomic origin, identifying pain intensity, referred pain, abnormal sensation, regularity and behaviour of symptoms, including 24 hour patterns, and aggravating and easing factors.

Special Questions[edit | edit source]

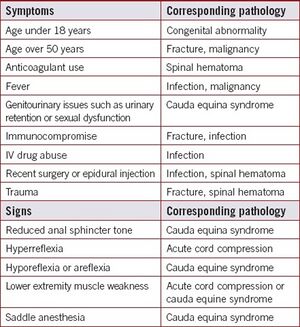

Red Flags for Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

It is important to consider serious spinal conditions during any assessment of back pain. The red flags listed below may flag your attention to spinal conditions listed below that may warrant urgent, further investigation (DePalma, 2020).

Other flags[edit | edit source]

It is important to consider and screen for alternative flags (yellow, orange, blue and black) which may interfere with physiotherapy management.

Low Back Pain objective assessment[edit | edit source]

The NICE guidelines for low back pain and sciatica highlight the importance of considering alternative diagnoses, and if they are suspected refer on accordingly (NICE, 2016). As well as clearing serious pathology during both the subjective questioning and objective testing, clinicians must clear lower limb pathologies due to the likelihood of the lumbar spine referring symptoms to that joint too (Physiopedia c, n.d.).

Observation[edit | edit source]

Movement patterns[edit | edit source]

- Gait and sit to stand- observe the patient from the very start!! How do they stand from the chair in the waiting room? How do they walk into the consultation room? Do they have an antalgic or Trendelenburg gait pattern?

- How are they sat in the chair; do they sit comfortably?

Posture and alignment[edit | edit source]

- Lordosis

- Kyphosis

Assess in sitting and standing to see if positioning has an impact on this.

Other observations[edit | edit source]

- Body type

- Attitude and beliefs

- Facial expressions

- Skin

- Hair

- Leg length discrepancy

Functional tests[edit | edit source]

1. Assess the movement they report struggling with the most.

2. For back pain, a squat test can highlight other lower limb pathologies, however if this is negative you do not need to test peripheral joints in lying. These have been shown to be reliable tests that can differentiate between overall strength ability of patients too (Drake, Kennedy and Wallace, 2017).

Always relate the functional testing to their ability, and goals aiming towards the activities they want to get back to achieving.

Movement testing[edit | edit source]

- Active range of motion (AROM)

- Passive range of motion (PROM) /overpressure

- Muscle strength testing (resisted isometrics in flexion, extension, side flexion, rotation, and testing core stability and functional strength tests)

Movement control testing[edit | edit source]

There are six motor control tests that can be used to identify reduced movement control and poor lumbar movement control, which are discussed in detail here. A significant difference was found in a study by Luomajoki et al (2008) with patients with low back pain and subjects without back pain regarding their ability to actively control movements in the low back.

Neurological assessment[edit | edit source]

See low back pain neurological assessment.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Reliability of manual palpation in the assessment of low back pain varies greatly, and the validity of these tests are commonly used by manual therapists and clinicians (Nolet et al., 2021). However, these tests can give some insight into a patient’s affected lumbar segmental level.

Special tests[edit | edit source]

See lumbar assessment here for more details.

Psychosocial assessment[edit | edit source]

See here for psychosocial approach to treatment.

Neck pain assessment[edit | edit source]

Subjective assessment

Take a detailed history around the neck pain. Some areas to explore include:

- Onset of the pain- acute/chronic/recurring/sudden/related to trauma or a particular activity.

- Nature and location of the pain- any radiation.

- Pain severity

- Occupational and social history.

- Medical and drug history.

- Symptoms of anxiety or depression.

- Previous injury or infection.

- Presence of fever.

- History of cancer.

- Presence of symptoms of spinal cord compression- lower limb weakness or altered sensation, disturbance of bowel or bladder function (NICE c,2023).

Objective

Conduct a physical examination to explore the potential causes of the neck pain further:

- Clear the shoulder and thoracic spine.

- Assess the appearance of the neck, including posture.

- Inspect the skin (e.g. for rashes or bruising)

- Assess range of motion- flexion, extension, side flexion, rotation.

- Palpate the neck for tenderness (Significant specific bony tenderness or midline tenderness is suggestive of other pathology).

- Check for cervical lymphadenopathy (could suggest infection, malignancy or an inflammatory cause)

- Assess deep neck flexor muscle strength

(NICE c, 2023)

Perform a neurological examination:

- Myotomes (power).

- Tone.

- Reflexes.

- Dermatomes (sensation) (NICE c,2023)

Special tests for cervical radiculopathy

A combination of special tests can be used to help identify cervical radiculopathy:

- The spurlings test

- Arm squeeze test

- Axial traction

- Upper limb neurodynamic tests (NICE a,2023)

Imaging

Cervical X-rays and other imaging/investigations are not routinely required. However, MRI is indicated in people with complex cervical radiculopathy, for example if there is reason to suspect myelopathy/abscess, progressively worsening objective neurological findings or failure to improve after 4-6 weeks of conservative treatment (NICE a, 2023).

Breathing Pattern Assessment[edit | edit source]

Before starting the assessment, it is important to know how breathing patterns normally present. Resting respiratory rate changes throughout human lifespans:

- At rest a baby will breathe 35-58 breaths per minute

- Toddlers will breathe 15-22 breaths per minute

- Adolescents 12-16 breaths per minute

- Once lungs have fully developed, around age 22, the resting rate will be 10-14 breaths per minute.

A typical pattern of breathing is a 1:2 ratio of exhalation to inhalation, with a slight pause at the end of exhalation. Breathing should be nasal/abdominal. A normal breathing pattern is important to maintain homeostasis and PH.

Key assessment tests for breathing pattern disorders include:

- Sniff test- Therapists places their hand below the patients xiphoid process. The patient performs a sniff and the therapist should feel an upward motion of the abdominal wall. This test assesses bilateral diaphragm function.

- Breath Hi-Low test - Patient is either in seated or supine. Therapist places hands on the patients chest and stomach. The patient is asked to exhale fully and inhale normally. The therapist observes for where the movement initiates, particularly looking for lateral expansion and upward hand pivot

- Seated lateral expansion- Therapist places hands on lower thorax and abdomen and looks for symmetrical lateral expansion during breathing.

- Breath holding- Ask the patient to exhale and then hold their breath. People should normally be able to hold their breath for 25-30 seconds. If a patient holds their breath for less than 15 seconds it indicates a low tolerance for CO2.

- Breathing wave- Patient lies prone. Patient breaths normally and the spine should move in a wave-like pattern towards the head. Segments that rise as a group may indicate restrictions.

- Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM)

Assessment of the MSK system:[edit | edit source]

- Observe for elevated or depressed ribs

- Check muscle tone and length (particularly in the trapezius, scalene, SCM, latissimus dorsi and quadratus lumborum)

- Assess for changes in mobility of the thoracic and rib articulations

Assessment of respiratory function[edit | edit source]

- Oximetry - measures SPO2

- Capnography - measures end tidal CO2 levels in exhaled air

- Peak expiratory flow rate - using a spirometer

- Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are various outcome measures used in low back pain, often questionnaire based to account for patient beliefs as well as functional impact of low back pain (). One of the most used tools is the Roland Morris disability questionnaire, as this has been found to reveal substantial burden of chronic low back pain on functional tasks including walking, stairs, and chores (Burbridge et al., 2020). Other studies have been evaluated for their responsiveness to determine which would best measure clinically meaningful change in this population, including Oswestry disability index, patient specific functional scale (PSFS), and the pain self-efficacy questionnaire (PSEQ). The PSFS and PSEQ were found to be more responsive following participation in a back class programme suggesting these may be the most appropriate to measure real change after these interventions (Maughan and Lewis, 2010).

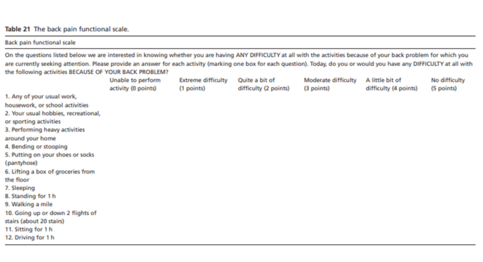

Low back pain outcome measure

The back pain functional scale (BPFS) measures level of function when experiencing back pain and is based on the International Classification of Function (ICF) scale to determine independence. 12 simple-to-follow questions determine levels of function and discomfort felt with the highest score available being 60 with each question scoring a maximum of 5 on a Likert Scale (0-5). Test-retest was determined to be 0.82 suggesting the PROM has consistent results across several timeframes (Stratford and Binkley, 2000). It closely correlates to the Roland Morris Questionnaire Scores but is more successful in detecting clinical change (Koc and Baar, 2022).

Neck Pain Outcome Measures

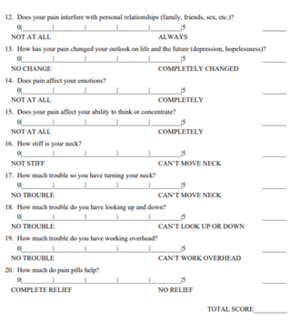

Commonly used outcome measures are the Neck Disability Index (NDI) and The Neck Pain and Disability (NPAD). The NPAD is a validated measure with high test-retest validity of 0.81 to 0.98. The 20-item scale with 4 domains including assessment of function, emotional and cognitive impacts and pain intensity aims to provide clinicians a tool to identify areas of concern and patient perceptions of neck pain (Chan, Clair and Edmonston, 2009). Patients score 0 – 100 with higher scores meaning greater impact and disability (Jorritsma et al, 2010).

The NDI differs by focusing on the amount of disability experienced in everyday life with neck pain. It has 10 questions with 7 being functional activities, 2 on symptoms and 1 on concentration. [Figure 2]. Test-retest validity was found at 0.50 to 0.97 and a maximum of 50 points can be scored, indicating higher scores of disability (Jorritsma et al, 2010).

Both are validated measures to investigate chronic non-traumatic and traumatic neck pain patients in several countries and languages (Scherer et al, 2008).

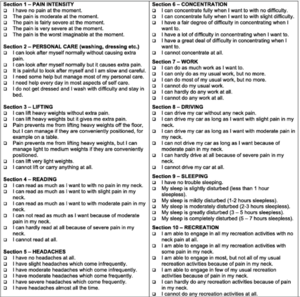

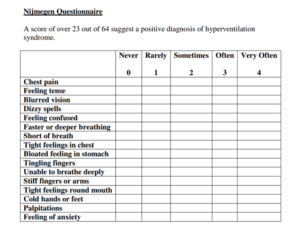

Breathing Dysfunction Outcome measure

The Nijmegen Questionnaire is a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) that identifies symptoms of respiratory distress and can diagnose hyperventilation syndrome. Higher scores represent higher dysfunction or distress in the respiratory system (Chapman et al, 2023). It involves 16 questions focusing on discomfort and symptoms occurrence experienced by patients [Figure 3]. It has a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 95%.

A diagnosis of abnormal breathing patterns is determined by comparing to a score in a normal population determined at 10 – 12 ± 7 for English Belgian and Dutch patients (Dixhoorn and Folgering, 2015). Therefore, a score higher than 23 is deemed to be sufficient for diagnosis.

Those with anxiety or depression have a higher breathing dysfunction than the general population but the Nijmegen questionnaire is unable to establish a differential diagnosis between anxiety disorders or breathing dysfunction (Naylor, Haines and Fowler, 2015).

Investigations[edit | edit source]

Has the patient had any other investigations such as blood tests or radiology (x-ray, MRI, CT, ultrasound)?

Has the patient had any operations/procedures carried out for a similar condition or presentation in the past? What was the treatment given for this i.e., have they had physiotherapy interventions prior to this.

‘Bringing the two together’ – Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders interventions.[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

See here for information on medical management for low back pain and breathing pattern disorders.

Physical Interventions[edit | edit source]

Normal breathing mechanics play a key role in posture and spinal stabilisation, and breathing pattern disorders can contribute to pain and motor control deficits (Bradley and Esformes, 2014). This study showed that even healthy individuals who exhibited biochemical and biomechanical signs of breathing pattern disorders were significantly more likely to score poorly on the Functional Movement Screen, despite any pain being experienced by the patient.

The results of one study have highlighted the importance of diaphragmatic breathing to reduce implications on muscular imbalances, motor control alterations and physiological adaptations (Bradley and Esformes, 2014).

One study suggests the diaphragm and transverse abdominis are key muscles in provision of core stability, but there is a reduction of support given to the spine, by the muscles of the torso, if there is both a load challenge to the low back combined with a breathing challenge (Chaitow, 2004).

A randomised controlled trial concluded that breath therapy was favoured at six-eight weeks post intervention, and physical therapy was favoured at six months, however overall changes in measures of pain and disability with back pain were comparable to those from physical therapy (Mehling et al., 2005).

Additionally, one study found that in a group of patients with varying degrees of low back pain, motor control activities created altered breathing patterns in around 71% of these (Ostwal and Wani, 2014). This correlates with data gained by Chaitow (2004), where they concluded the transverse abdominis and diaphragm are key muscles in both core stability and respiration, and the coordination of these 2 roles may be complicated when the demand of one task increases. This matches the results by Ostwal and Wani (2014), where the biggest change in breathing patterns was found during the knee bend fall out test at 91% patients had altered patterns.

Due to this variety of evidence supporting the need for optimal function of the transverse abdominis and diaphragm function in trunk stability and normal breathing mechanics, it is important to identify these in clinic and target exercises towards the breathing pattern disorder as well as the symptoms from the low back pain.

In relation to treatment, many interventions have certain principles in common (CliftonSmith and Rowley, 2011).

1. Education on the pathophysiology of the disorder

2. Self-observation of one’s own breathing pattern

3. Restoration to a basic physiological breathing pattern: relaxed, rhythmical nose-abdominal breathing

4. Appropriate tidal volume

5. Education of stress and tension in the body

6. Posture

7. Breathing with movement and activity

8. Clothing awareness

9. Breathing and speech

10. Breathing and nutrition

11. Breathing and sleep

12. Breathing through an acute episode

Breathing exercises[edit | edit source]

Breathing programmes have been shown to be effective in patients with chronic low back pain, and have been able to reduce pain, improve respiratory function, and/or health related quality of life (Anderson and Huxel Bliven, 2017; Physiopedia b, n.d.).

Breathing control: (NHS University Hospital Southampton, 2023).[edit | edit source]

To breathe in a more natural way, encourage your patient to sit in a comfortable armchair or lie on the bed, and release any tension in your neck and shoulders. Place on hand on your chest, and one on top of your tummy. Focus on directing air to the stomach, to use your diaphragm more effectively.

Keep a normal breath rate and size whilst practicing this.

When the patient has been able to replicate diaphragmatic breathing in lying, progress to encouraging to check their pattern of breathing when walking, maintaining nose breathing.

Breathing through a balloon: (Smale, 2018).[edit | edit source]

90-90 Hip Lift with Balloon- Video outlining the below instructions:

1. Encourage the patient to adopt a 90-90 hip lift.

2. Get patient to put their tongue on the roof of their mouth and breath in through their nose.

3. On the breath out get them to lift their pelvis so their back is flat on the bed.

4. Place tongue back on the roof of the mouth and breath in through nose again.

5. Place balloon to lips and breath out into the balloon. Hold for 3-4 seconds without squeezing neck of balloon.

6. Repeat step 4-5 three times and then breath out and relax.

This can help patients retrain their zone of apposition to synchronise their diaphragm and abdominal wall. Integrating these breathing exercises with the following core strengthening exercises should be beneficial for patients with low back pain and breathing pattern disorders.

Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders Interventions[edit | edit source]

To strengthen the appropriate muscles such as transverse abdominis, gym ball exercises have been shown to have a significant impact on biomechanical changes, respiratory variables, and joint position sense in participants with low back pain (Lim, 2020).

These exercises may include:

- Side bridging

- Gym ball partial curl ups

- Supine bridging with single leg raise

- Gym ball push ups

- Gym ball single leg holds

- Gym ball roll outs with an unstable support

These above exercises all increase lumbar spine stability and increase abdominal activity.

Other abdominal training exercises that may help relieve back pain may consist of:

- Bird dog/superman exercises

- Glute bridges

- Squats

- Plank exercise

- Dead bug exercises

- Knee rolls (to either side)

- Cat-cow positions

Other considerations (NHS University Hospital Southampton)[edit | edit source]

- Lifestyle changes- slow down and set realistic goals. Encourage pacing and energy conservation.

- Speech- continue to use abdominal, low-chest breathing pattern, take a relaxed breath out before starting to talk and breath softly through the nose.

- Sleeping- follow a relaxing night-time routine, reduce stress levels, avoid caffeinated drinks, daytime napping, and late and spicy meal at night.

- Relaxation- visualisation of a pleasant situation, body awareness exercises

‘Bringing the two together’ – Neck Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders interventions.[edit | edit source]

Most literature for the management of patients with a combination of neck pain and breathing pattern disorders look at routine physiotherapy compared to routine physiotherapy alongside breathing pattern disorder interventions. It is important to include elements of usual care for neck pain in addition to respiratory interventions to ensure the problem is managed from all angles. This will provide the best chance of effectively managing the patients symptoms.

Routine neck management includes:

- Reassurance - neck pain is a common problem that usually resolves within a few weeks.

- Advice and education- around pillows for sleeping, return to activity and normal lifestyle, driving, speaking to GP/pharmacist around pain medication and discourage use of cervical collars.

- Physiotherapy exercises- strengthening, stretching, range of motion, manual therapy and advice on participation in regular exercise (e.g. Pilates or yoga).

- Consider referral for psychological therapy if there are psychological symptoms or risk factors.

- Consider referral to occupational health if pain is related to work.

- Consider referral to pain clinic if the person has had neck pain for more than 12 weeks and is not improving with treatment (NICE d, 2023).

Additional management techniques for people with a combination of neck pain and dysfunctional breathing should be used, as discussed below.

Breathing re-education (diaphragmatic breathing) alongside routine physiotherapy

Breathing re-education has been found by some studies to improve a range of outcomes for neck pain patients including:

- Pain

- Active range of motion in cervical flexion and extension

- Cervical flexor muscle strength and endurance

- Neck disability index score

- Pulmonary functions including forced vital capacity (Anwar et al a, 2022) (Anwar et al b, 2022)

A double blind randomised control trial by Anwar et al (b) (2022) found the addition of breathing re-education exercises to routine physiotherapy exercise significantly improved pain, cervical flexion and extension active range of motion, cervical flexor strength and neck disability index score, compared to routine physical therapy group. The pulmonary functions (mean score for FEV1/FVC ratio) were significantly improved in breathing reeducation group.

The routine physical therapy group received a treatment comprised of infrared radiation (IRR) to the cervical region for 10 minutes and isometric exercises for cervical muscles (flexors and extensors) in supine lying with 10 second hold and 20 repetitions. After that each patient was instructed to perform placebo breathing exercises (unsupervised random shallow breathing routine) for 15 minutes (Anwar et al b, 2022).

The breathing reeducation group completed both the routine physiotherapy above and breathing re-education. They assumed a semi-Fowler’s position (To keep the torso supported and abdominal wall relaxed) and performed diaphragmatic breathing. They inhaled slowly and deeply through the nose, from functional residual capacity to total lung capacity with a three-second inspiratory hold, then exhaled slowly through the mouth up to five seconds. The breathing exercises were performed in 3 sets for 15 minutes, each set lasted for 3 minutes with a rest of 2 minutes between each set. In between the repetitions of the diaphragmatic breathing exercise, the patient was told to breathe normally. Patients of both groups received the intervention five days a week for eight weeks (Anwar et al b, 2022).

A randomised control trial by Anwar et al (a) (2022) also concluded that breathing re-education combined with other physiotherapy management is effective for improving the neck flexor strength in people with neck pain. It additionally found it to be beneficial for improving forced vital capacity. Very similar interventions were used for both groups as in the study by Anwar et al (b)(2022).·

The between-group analysis showed a statistically significant increase in the strength of the neck flexors for the breathing re-education group. The endurance and strength of neck extensors had no between-group differences. For pulmonary function, there was a statistically significant improvement in FVC for the breathing reeducation group but FEV1 and FEV1/FVC percentage had no between-group differences. Anwar et al suggest that improved strength of cervical muscles may lead to less disability and improved quality of life. They suggest improvement in FVC will lead to more oxygen available to the neuromuscular system which may lead to less stress and neck pain (Anwar et al a, 2022) .

Balloon respiratory exercises alongside routine physiotherapy

A randomised assessor-blind control trial by Dareh-deh (2022) found that although adding respiratory exercises to routine physiotherapy exercises did not significantly improve pain experience compared to routine physiotherapy alone, both groups had a significant decrease in pain experienced. Only the combined group (respiratory and routine physiotherapy) experienced positive changes in their breathing pattern, suggesting the addition of respiratory exercises is beneficial if you are managing both neck pain and respiratory pattern disorders.

The routine physiotherapy contained resistance and stretching exercises for 45-60 minutes per session, three sessions a week for eight weeks.

Resistance exercises included:

- Side-lying external rotation (Teres minor, infraspinatus).

- Prone horizontal abduction with external rotation (Middle trapezius, Lower trapezius, Rhomboids, Infraspinatus, Teres minor).

- Y-to-I exercise (Middle trapezius, Lower trapezius, Serratus anterior).

- Chin tuck in supine (Longus colli, Longus capitis).

Stretching exercises included:

- Static levator scapulae stretch.

- Pectoralis minor stretch.

- Static sternocleidomastoid stretch.

In the combined group, balloon breathing respiratory exercises were added to the ones above. These exercises were conducted for 4 sets, two sessions a day, three days a week for eight weeks:

- The subject lies in supine, placing the soles of their feet against the wall so that the ankle, knee, and thigh joints are at a 90-degree angle.

- The subject places a 3–4-inch ball between their knees and maintain pressure on it during the whole training period with their back in a flat pelvic tilt.

- Holds the right hand above the head and the left hand with the balloon. They inhale through the nose in three-four seconds and then exhale slowly into the balloon.

At eight weeks, routine physiotherapy showed a 57.5% improvement and the combined group showed a 62.4% improvement from the baseline for pain. For respiratory pattern the combined group showed a 37.5% improvement for respiratory balance and a 19.1% improvement for number of breaths from baseline. These respiratory changes were not significant for the routine physiotherapy group (Dareh-deh, 2022).

other interventions

A systematic review by Tatsios et al (2022) concludes that there is currently some emerging evidence that core stability exercises supplemented with respiratory exercises, and re-education of diaphragmatic breathing improve musculoskeletal and respiratory outcomes in patients with non-specific chronic neck pain. However, the results of the review should be taken with caution as the 16 randomised control trials used were of low quality and high heterogeneity.

The systematic review looked in part at the effects of respiratory related interventions (RRI) on neck pain, disability and respiratory outcomes. RRI include:

- Diaphragmatic breathing re-education exercises

- Pursed lips breathing exercises

- Diaphragm relaxation exercises

- Deep slow breathing

- Respiratory exercises with the use of a spirometer

- Respiratory exercises with the use of a balloon

- Respiratory exercises focusing on proper inhalation, exhalation, and chest expansion.

The respiratory exercises were prescribed in various combinations and dosages, and, for many clinical trials, were not delivered as the main intervention (Tatsios et al, 2022).

The effects of RRI compared to the control on pain were evaluated by eight studies including 338 participants. A large effect size favoring RRI with statistical significance (p < 0.001) and no statistical heterogeneity was shown but with low quality evidence (Tatsios et al, 2022).

The effects of RRI compared to control interventions on disability were evaluated by five studies including 163 participants in total. A large effect size with statistical significance (p = 0.01) favoured RRI. However there was high statistical heterogeneity and it was based on very low-quality evidence (Tatsios et al, 2022).

The effects of RRI compared to control on maximum voluntary ventilation (MVV) and chest wall expansion (CWE) were evaluated by two studies including 42 participants in total. A large effect size was noted favoring RRI but without statistical significance (p = 0.15). Similarly, a large effect size was noted for CWE favoring RRI but with no statistical significance (p = 0.05) (Tatsios et al, 2022).

Tatsios et al (2022) suggest that RRI should be considered when prescribing exercises for this patient population. They suggest this may be due to breathing disorders frequently coexisting with/directly impairing motor control of all muscles surrounding the spine. The effectiveness of RRI in musculoskeletal and respiratory outcomes calls for additional research investigations of high methodological quality.

Evidence:[edit | edit source]

Inspiratory Muscle Training Affects Proprioceptive Use and Low Back Pain. Janssens et al (2015).[edit | edit source]

Aim: To investigate the effect of inspiratory muscle training (IMT) on proprioceptive use during posture control in patients with NSLBP.

Design: RCT with 28 participants with NSLBP. Score of at least 10% on Oswestry disability index. No participants showed evidence of airflow obstruction (FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC). Excluded if had previous surgery, respiratory disorder, physical therapy, pain medication, specific balance problems, neck pain or lower limb problems.

Outcome measures: Proprioception in upright standing by measuring centre of pressure displacement during local muscle vibration, inspiratory muscle strength (PIMax), severity of LBP (NRS scale) and disability (ODI-2, fear avoidance beliefs questionnaire and Tampa scale for kinesiophobia)

Intervention methods: High intensity IMT training and low IMT over 8 weeks. IMT involved breathing through a mouthpiece with their nose occluded while standing upright. Resistance was added with each inspiration so participants generated a negative pressure of 60% of their PIMax (high intensity) or 10% of their PIMax (low intensity). Participants performed 30 breaths, twice daily 7 days a week with a (15 breaths a minute frequency). Both groups were coached diaphragmatic breathing pattern rather than thoracic breathing.

Results:

Proprioception: Significant positive correlation observed in change of CoP displacement during LP vibration on an unstable surface (r = 0.44, P = 0.034), suggesting PImax values are associated with a more facilitated back proprioceptive use during postural control.

Inspiratory muscles strength: significant between groups (p=0.05). High-IMT group had significantly increased PIMax post intervention (94 ± 30 vs 136 ± 34 cm H2O) (Δ 42 cm H2O, P = 0.001). Low-IMT did not influence PIMax.

LBP severity: significantly lower in the high-IMT group compared with the low IMT group (p=0.013). Severity of LBP decreased significantly in the high IMT group (5 ± 2 vs 2 ± 2) (Δ 3, P = 0.001) – this change was clinically meaningful (Bahreini et al, 2020). No change was observed in the low-IMT group.

Disability: No difference between groups. Neither group had a significant difference pre or post intervention. Scores in fear avoidance beliefs questionnaire and Tampa scale for kinesiophobia were not significantly different between groups or after the interventions.

Conclusions: It may be possible to reverse suboptimal proprioceptive use in patients with LBP by implementing high intensity IMT and supporting the role of inspiratory muscle dysfunction in patients with LBP.

Strengths and limitations: + Adequately powered to detect a clinically relevant difference (14 participants per group, 08, two tailed, a= 0.05) + Valid and reliable OM used

-Volunteer sampling so may lead to selection bias and an sample of that is not representative of the wider population.

Development of a screening protocol to identify individuals with dysfunctional breathing. Kiesel et al., 2017.[edit | edit source]

Aim- To develop a breathing screening procedure that could be utilised by fitness and healthcare providers to screen for the presence of disordered breathing.

Design- Diagnostic test study approach to establish the diagnostic accuracy of the newly developed screen for disordered breathing.

Participants- A convenience sample of 51 participants (27 females, 24 males) were included. Subjects were excluded if they were participating in rehab for any disorder, if they had a neurological or cardiovascular comorbidity known to impair MSK function, or if they could not read or speak English.

Outcome measures- Reference measures were obtained for each of the three dimensions of dysfunctional breathing. Resting capnography data was collected as subjects completed the questionnaires of activity levels. The Hi-Lo test was then performed, followed by the breath hold time, and then the functional movement screen. The Hi-Lo test was taken to determine if a subject had a biomechanical breathing problem (normal diaphragmatic breathing or abnormal). Capnography was taken via nasal cannula to determine ETCO2, and if they had a biochemical breathing problem. The Nijmegen questionnaire addresses the psychophysiological dimension. Breath hold time measured the functional residual capacity and functional movement scale was used as a measure of movement dysfunction.

Results- 5 subjects demonstrated normal breathing, 13 failed at least one measure, 21 failed at least two, and 12 failed all three. There was a significant difference in activity level for those who passed and failed the Hi-Lo test (p=0.02), and a difference in composite functional movement screen scores between those who passed and failed the Hi-Lo test (p<0.01). The only clinical test that related in some manner to all three dimensions of dysfunctional breathing was the functional movement screen. These findings help validate previous findings that link movement and breathing dysfunction.

Strengths and weaknesses:

+ Only tests that could be performed by non-healthcare personnel were considered to allow the screen to have utilisation in fitness applications as well as the rehabilitation fields.

+ 89% chance that if the screen is passed that dysfunctional breathing is not present- high likelihood.

- Small sample size to consider the application of a new screening tool

- High incidence of dysfunctional breathing patients in this population due to only 5 subjects passing the screen which is higher than expected of a general population

Conclusion- Four questions and a breath hold test, used in combination, were found to be highly sensitive to identify those with some dimension of dysfunctional breathing.

Can Slow Deep Breathing Reduce Pain? An Experimental Study Exploring Mechanisms (Jafari et al, 2020)[edit | edit source]

Aim: The study aimed to investigate

- The extent to which complying with any instructed breathing task reduces pain

- Whether instructed slow deep breathing at.1 Hz produces a greater pain reduction than instructed breathing at an individual’s normal breathing frequency

- Whether the inspiration/expiration ratio during slow deep breathing influences pain

- How different slow deep breathing patterns influence cardiac vagal activity indices, systolic blood pressure, and parameters of baro-reflex function.

Design: Within-subject experimental study

Participants: 52 healthy individuals (both genders) between 18 and 30 years old. The exclusion criteria were: self-reported cardiovascular, respiratory, or neurological disorders, current acute pain, pacemaker or any other electronic medical implant, hearing or visual impairment, psychiatric disorders or recent psychological trauma, regular medication intake (except contraceptives), and pregnancy.

Outcome measures:

Respiration: Respiratory movements were measured using a standard, well-accepted setup to measure respiration in psychophysiological research (rubber bellows attached to an aneroid pressure transducer and resistive bridge coupler). After a rest period of 5 minutes, a 7-minute baseline measurement of the breathing pattern was acquired to determine the participant’s spontaneous breathing frequency and inspiration: expiration ratio.

Blood pressure: Blood pressure was continuously and noninvasively measured at the middle phalanx of the middle finger of the left hand using the Portapres Model-2 device with 5 milliseconds temporal resolution.

Electrocardiography: The ECG was measured conform recommendations and guidelines in the field.

Pain ratings: Using the AFFECT software, a computerized 100-point numerical rating scale,39 ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst possible pain) was displayed on the screen promptly following each pain stimulus. Subjects were asked to indicate the intensity of pain using the mouse.

Thermal stimulation: A thermal stimulator generated heat pain. The device has built-in safety limits. To measure the pain threshold, a thermal probe with a baseline temperature of 32°C was attached to the palmar side of the left wrist. The temperature was increased at a rate of 1°C/s, up to a maximum of 50°C. Participants were instructed to focus and report (by pressing a mouse button) at which point the sensation of warmth changed into pain.

Intervention methods:

During the study, participants were seated on a chair with back and arm supports in a quiet temperature-controlled room and the researcher observed from an adjacent control room using a continuous live video feed.

Four different respiratory patterns were used:

- Unpaced breathing (spontaneous breathing without any instructions)

- Paced breathing during which breathing was individually set at the natural frequency, with the inspiration/expiration ratio of each participant derived from the baseline measurement

- Slow deep breathing at 6 breaths per minute with a high inspiration/expiration ratio

- Slow deep breathing at 6 breaths per minute with a low inspiration/expiration ratio

In the 3 paced breathing conditions, a bar graph displayed at the screen in front of the participants moved vertically at the desired rhythm in order to cue the targeted breathing pattern. The participants practiced the paced breathing under supervision before the trial started.

Participants performed each of the 4 breathing patterns for 8 minutes in counterbalanced order. During each breathing condition, 12 thermal stimuli were applied. Each intensity (1°C, 2°C, and 3°C above the pain threshold) was applied 4 times per condition in a random order. The stimulus duration was 5 seconds, and the interstimulus interval varied randomly between 35 and 45 seconds. After each thermal stimulus, the pain scale appeared on the computer screen and participants rated the intensity of the pain induced by the stimulus.

Results:

As can be expected, pain ratings increased with increasing temperature of the heat stimulus. Compared to unpaced breathing, pain ratings were lower during each of the 3 instructed breathing patterns and these effects were significant for each of the 3 temperatures.

Findings indicate that slow deep breathing with low inspiration/expiration ratio but not slow deep breathing with high inspiration/expiration ratio, was associated with lower pain ratings compared to paced breathing. This effect was significant for temperatures +2°C and +3°C, but not for +1°C.

Results show that slow deep breathing with low inspiration/expiration ratio was associated with lower pain ratings than slow deep breathing with high inspiration/expiration ratio, but this effect was only significant for the highest temperature (+3°C).

Overall, the results suggest that effects of breathing pattern tend to grow stronger with increasing temperatures.

Conclusions: In summary, the present study found that paced breathing can reduce pain reports and that this hypoalgesic effect is enhanced when breathing is paced at a lower frequency (6 breaths per minute) with a low inspiration/expiration ratio (ie, prolonged expiration). Mechanisms underlying pain reduction during instructed breathing may include top-down influences including attentional re-allocation, expectations of paced breathing affecting pain experience, stress reduction, and/or emotional modulation, which warrant greater attention in future research. Further studies are also required to evaluate the influence of slow deep breathing on pain using various pain modalities, in a larger sample. This suggests that this intervention could be helpful for the population of people with both spinal pain and breathing dysfunction as paced breathing may reduce their pain at the same time as retraining their breathing.

Strengths:

- Used reliable and widely-accepted outcome measures

- Participants were seated on a chair with back and arm supports in a quiet temperature-controlled room and the researcher observed from an adjacent control room using a continuous live video feed which limits the impact of having other people in the room on the participants breathing control.

- Used 4 different breathing techniques to determine the most optimal method.

Limitations:

- Only tested healthy individuals

- Only tested pain associated with high temperatures.

- Four out of the 52 participants in this study were excluded due to technical problems.

- Did not control for potential effects of expectation or different levels of attentional re-allocation and stress reduction caused by the breathing patterns for pain management.

- Gender effects could not be investigated in this study due to the limited number of participants and an unbalanced gender distribution.

- Would have been stronger as an RCT.

Depression and anxiety as major determinants of neck pain: a cross-sectional study in general practice (Blozik at el, 2009)[edit | edit source]

Aim: To identify psychological, socio-demographic and medical factors that interact with neck pain and the association between them.

Design: A Cross-sectional survey collecting data from 15 general practices in Germany within a 30km radius of Gottingen. Data was anonymised with only age, sex and diagnosis recorded as identifiable data. Descriptive statistics and linear regression models were used in data analyses.

Outcome measures: NPAD and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scores (HADS).

Population: People reporting at least one episode of neck pain between March 2005 and April 2006. Participants were excluded if they presented with trauma-related injuries to the neck, cancers, terminal illness or severe cognitive impairment and was limited to German- speakers only. Participants who were seen by a locum or moved out of the 30km radius were excluded.

Results: Depression and anxiety levels were significantly associated with increased levels of neck pain. Those with the highest levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms were much more likely to be found in the group of people with the greatest levels of neck pain. Results were statistically significant with p <0.005

Weaknesses: Based in a German population so reduces generalisability and external validity. As data was collected between 2005 and 2006 means study is outdated and may not be relevant to the current population and supporting evidence. Participants included were 78% female so results are more generalisable to women in Germany compared to men. Due to the nature of using PROMs, it introduced a risk of attrition bias

Conclusion: Supports positive trends and statistical significance between anxiety or depression and neck pain felt. Those with higher levels of neck pain should be screened for psychological distress due to the links found between greater NPAD and greater HADS scores to ensure a biopsychosocial approach to recovery.

References:[edit | edit source]

Anderson, B.E, and Huxel Bliven, K.C., 2017. The Use of Breathing Exercises in the Treatment of Chronic, Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 26(5), pp. 452-458.

Anwar, H., Arsalan, S., Zafar, H., Ahmed, A., Gillani, S. and Hanif, A.(a) (2022) Effects of breathing re-education on endurance, strength of deep neck flexors and pulmonary function in patients with chronic neck pain: A randomised controlled trial. South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 78(1). [Online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9082229/ [Accessed 16/05/2023]

Anwar, H., Arsalan, S., Zafar, H., Ahmed, A., and Hanif, A.(b) (2022) Effects of breathing reeducation on cervical and pulmonary outcomes in patients with non specific chronic neck pain: A double blind randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 17(8). [Online] Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0273471#sec007 [Accessed 16/05/2023]

Bahreini, M., Safaie, A., Mirfazaelian, H. and Jalili, M. (2020). How much change in pain score does really matter to patients? The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(8), pp.1641–1646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158489.

Balagué, F., Mannion, A.F., Pellisé, F. and Cedraschi, C. (2012). Non-specific low back pain. The Lancet, [online] 379(9814), pp.482–491. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21982256/ [Accessed 17 May 2023].

Beeckmans, N., Vermeersch, A., Lysens, R., Van Wambeke, P., Goossens, N., Thys, T., Brumagne, S. and Janssens, L. (2016). The presence of respiratory disorders in individuals with low back pain: A systematic review. Manual Therapy, 26, pp.77–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2016.07.011.

Blozik, E., Laptinskaya, D., Herrmann-Lingen, C., Schaefer, H., Kochen, M.M., Himmel, W. and Scherer, M. (2009). Depression and anxiety as major determinants of neck pain: a cross-sectional study in general practice. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, [online] 10(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-13. Available at: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-10-13 [Accessed 17 May 2023].

Bradley, H, and Esformes, D.J., 2014. Breathing Pattern Disorders and Functional Movement. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 9(1), pp. 28-39.

Burbridge, C., Randall, J.A., Abraham, L, and Bush, E.N., 2020. Measuring the impact of chronic low back pain on everyday functioning: content validity of the Roland Morris disability questionnaire. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, 4(70).

Chaitow, L., Bradley, D. and Gilbert, C., 2002. Multidisciplinary approaches to breathing pattern disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Chaitow, L., 2004. Breathing pattern disorders, motor control, and low back pain. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 7(1), pp. 33-40.

Chan Ci En, M., Clair, D.A. and Edmondston, S.J. (2009). Validity of the Neck Disability Index and Neck Pain and Disability Scale for measuring disability associated with chronic, non-traumatic neck pain. Manual Therapy, [online] 14(4), pp.433–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2008.07.005. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1356689X08001343 [Accessed 16 May 2023]

CliftonSmith, T. and Rowley, J. (2011). Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Physical Therapy Reviews, 16(1), pp.75–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/1743288x10y.0000000025.

Dareh-deh, H., Hadadnezhad, M., Letafatkar, A. and Peolsson, A. (2022) Therapeutic routine with respiratory exercises improves posture, muscle activity, and respiratory pattern of patients with neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. Scientific Reports, 12. [Online] Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-08128-w#Sec2 [Accessed 16/05/2023]

DePalma, M.G., 2020. Red flags of low back pain. JAAPA, 33(8), pp.8-11.

Deshmukh, M.P., Palekar, T.J. and Manvikar, N. (2022). Prevalence of Breathing Dysfunction in Musculoskeletal Complaints: A Cross Sectional Study. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 12(2), pp.146–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.52403/ijhsr.20220220.

Dixhoorn, J. and Folgering, H. (2015). The Nijmegen Questionnaire and dysfunctional breathing. ERJ Open Research, [online] 1(1), pp.00001-2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00001-2015. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5005127/ [Accessed 16 May 2023]

Drake, D., Kennedy, R, and Wallace, E., 2017. The Validity and Responsiveness of Isometric Lower Body Multi-Joint Tests of Muscular Strength: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine – Open, 3(23).

Gask, L, and Usherwood, T., 2002. The consultation. BMJ, 324(7353), pp. 1567-1569.

Hagins, M. and Lamberg, E.M. (2011). Individuals with Low Back Pain Breathe Differently Than Healthy Individuals During a Lifting Task. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 41(3), pp.141–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2011.3437.

Hall, H., 2014. Effective spinal triage: patterns of pain. Spring, 14(1), pp. 88-95.

Hendrick, P., 2016. Spinal Triage. [PowerPoint presentation]. Spinal Triage Diagram. Available at: https://moodle.nottingham.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=113500. [Accessed on: 17th May 2023].

Hodges, P.W. and Gandevia, S.C. (2000). Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. Journal of Applied Physiology, 89(3), pp.967–976. doi:https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.967.

Hodges, P.W., Sapsford, R. and Pengel, L.H.M. (2007). Postural and respiratory functions of the pelvic floor muscles. Neurourology and Urodynamics, [online] 26(3), pp.362–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20232.

Ionescu, M.F., Mani-Babu, S., Degani-Costa, L.H., Johnson, M., Paramasivan, C., Sylvester, K. and Fuld, J. (2021). Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in the Assessment of Dysfunctional Breathing. Frontiers in Physiology, 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.620955.

Jafari, H., Gholamrezaei, A., Franssen, M., Van Oudenhove, L., Aziz, Q., Van den Bergh, O., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., and Van Diest, I. (2020). Can slow deep breathing reduce pain? An experimental study exploring mechanisms. The Journal of Pain, 21(9-10), pp.1018-1030. [Online] Available at: https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/78117618/Vlaeyen_2020_Can_slow_deep_breathing_reduce.pdf [Accessed 17/05/2023]

Janssens, L., Brumagne, S., McConnell, A.K., Hermans, G., Troosters, T. and Gayan-Ramirez, G. (2013). Greater diaphragm fatigability in individuals with recurrent low back pain. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 188(2), pp.119–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.028.

JANSSENS, L., MCCONNELL, A.K., PIJNENBURG, M., CLAEYS, K., GOOSSENS, N., LYSENS, R., TROOSTERS, T. and BRUMAGNE, S. (2015). Inspiratory Muscle Training Affects Proprioceptive Use and Low Back Pain. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(1), pp.12–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000385.

Jones, M, & Rivett, D. (2004). Clinical Reasoning for Manual Therapists. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann.

Jorritsma, W., de Vries, G.E., Geertzen, J.H.B., Dijkstra, P.U. and Reneman, M.F. (2010). Neck Pain and Disability Scale and the Neck Disability Index: reproducibility of the Dutch Language Versions. European Spine Journal, [online] 19(10), pp.1695–1701. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1406-x. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989234/ [Accessed 15 May 2023].

Kahlaee, A.H., Ghamkhar, L. and Arab, A.M. (2017). The Association Between Neck Pain and Pulmonary Function: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, [online] 96(3), pp.203–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000608.

Kaminoff, L. (2006). What Yoga Therapists Should Know About the Anatomy of Breathing. International Journal of Yoga Therapy, 16(1), pp.67–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.17761/ijyt.16.1.64603tq46513j242.

Kent Community Health (2022). Dysfunctional breathing pattern. [online] Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust. Available at: https://www.kentcht.nhs.uk/leaflet/dysfunctional-breathing-pattern/ [Accessed 11 May 2023].

Kiesel, K., Rhodes, T., Mueller, J., Waninger, A, and Butler, R., 2017. Development of a screening protocol to identify individuals with dysfunctional breathing. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 12(5), pp. 774-786.

Koç, M. and Bayar, K. (2022). Chapter 44 - The back pain functional scale: Features and applications. [online] ScienceDirect. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128189887000029# [Accessed 17 May 2023].

Lewit, K. (1980). Relation of faulty respiration to posture, with clinical implications. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, [online] 79(8), pp.525–529. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/7364597 [Accessed 16 May 2023].

Lim, C.G., 2020. Comparison of the effects of joint mobilisation, gym ball exercises, and breathing exercises on breathing pattern disorders and joint position sense in persons with chronic low back pain. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science, 9, pp. 25-35.

Longo, U.G., Loppini, M., Denaro, L., Maffulli, N. and Denaro, V. (2010). Rating scales for low back pain. British Medical Bulletin, [online] 94(1), pp.81–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldp052. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article/94/1/81/308485#google_vignette [Accessed 17 May 2023].

Luomajoki, H., Kool, J., de Bruin, E.D, and Airaksinen, O., 2008. Movement control tests of the low back; evaluation of the difference between patients with low back pain and healthy controls. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 9(170).

Maughan, E.F, and Lewis, J.S., 2010. Outcome measures in chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J, 19(9), pp. 1484-1494.

Mayfield (2018). Neck Pain, neck pain treatment options Mayfield Brain & Spine Cincinnati, Ohio. [online] mayfieldclinic.com. Available at: https://mayfieldclinic.com/pe-neckpain.htm#:~:text=Signs%20and%20symptoms%20of%20neck [Accessed 16 May 2023].

Mehling, W.E., Hamel, K.A., Acree, M., Byl, N, and Hecht, F.M., 2005. Randomised, controlled trial of breath therapy for patients with chronic low-back pain. Altern Ther Health Med, 11(4), pp. 44-52.

Mountain Physiotherapy (2014). Neck Pain and Disability Scale, pg 1 [online] Available at: https://mountainphysiotherapy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Neck-Pain-and-Disability-Scale.pdf [Accessed 16 May 2023].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence., 2016. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed on: 13th May 2023.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEa) (2022). Back pain - low (without radiculopathy):What else might it be? [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/back-pain-low-without-radiculopathy/diagnosis/differential-diagnosis/ [Accessed 09/05/2023]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEb) (2022). Diagnosis of breathlessness. [Online] Available at:https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/breathlessness/diagnosis/ [Accessed 17/05/23]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEc) (2022). Sciatica (lumbar radiculopathy):What else might it be? [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/sciatica-lumbar-radiculopathy/diagnosis/differential-diagnosis/ [Accesssed 09/05/2023]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEa) (2023) Neck pain - cervical radiculopathy: How should I assess someone with suspected cervical radiculopathy? [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/neck-pain-cervical-radiculopathy/diagnosis/assessment/ [Accessed 12/05/2023]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEb) (2023) Neck pain - cervical radiculopathy: What else might it be?. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/neck-pain-cervical-radiculopathy/diagnosis/differential-diagnosis/ [Accessed 09/05/2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEc) (2023) Neck pain - non-specific: How should I assess someone with non-specific neck pain? [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/neck-pain-non-specific/diagnosis/assessment/[Accessed 09/05/2023]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEd) (2023) Neck pain - non-specific: Scenario: Management [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/neck-pain-non-specific/management/management/ [Accessed 12/05/2023]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICEe) (2023) Neck pain - non-specific:What else might it be? [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/neck-pain-non-specific/diagnosis/differential-diagnosis/ [Accessed 09/05/23]

Naylor, SD; Haines J; Vyas A; Fowler SJ; (2015). “M3 Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Breathing Pattern Disorders or Chronic Respiratory Disease.” Thorax 70.Suppl 3 (2015): A227–A228. [online] doi 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207770.430 Available at: https://thorax.bmj.com/content/thoraxjnl/70/Suppl_3/A227.full.pdf [Accessed 17 May 2023].

NHS Pathways (2019). Back Pain | Clinical pathways. [online] clinical-pathways.org.uk. Available at: https://clinical-pathways.org.uk/clinical-pathways/back-pain [Accessed 17 May 2023].

NHS Pathways (2019). Neck Pain | Clinical pathways. [online] clinical-pathways.org.uk. Available at: https://clinical-pathways.org.uk/clinical-pathways/neck-pain#:~:text=Assess%20for%20red%20flags%20including [Accessed 17 May 2023].

Nolet, P.S., Yu, H., Côté, P., Meyer, A., Kristman, V.L., Sutton, D., Murnaghan, K, and Lemeunier, N., 2021. Reliability and validity of manual palpation for the assessment of patients with low back pain: a systematic and critical review. Chiropr Man Therap, 29.

Ostwal, P.P, and Wani, S.K., 2014. Breathing patterns in patients with low back pain. International Journal of Physiotherapy and Research, 2(1), pp. 347-353.

Petty, N.J., 2018. Musculoskeletal Examination and Assessment, Fifth Edition. Elsevier Ltd.

Physiopedia a, n.d. Muscles of Respiration. Available at: Muscles of Respiration. [Accessed on: 17th May 2023].

Physiopedia b, n.d. Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders. Available at: Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders. [Accessed on: 17th May 2023].

Physiopedia c, n.d. Lumbar Assessment. Available at: Lumbar Assessment. [Accessed on: 17th May 2023].

Physiotutors.com a (n.d.) Cervical red flags [Online] Available at: https://www.physiotutors.com/physiotherapy/neck-pain/ [Accessed 12/05/2023]

Physiotutors.com b (n.d.) Physiotherapy for thoracic pain : Assessment and treatment. [Online] Available at:https://www.physiotutors.com/physiotherapy/thoracic-pain/ [Accessed 12/05/23]

Roussel, N., Nijs, J., Truijen, S., Vervecken, L., Mottram, S. and Stassijns, G. (2009). Altered breathing patterns during lumbopelvic motor control tests in chronic low back pain: a case–control study. European Spine Journal, 18(7), pp.1066–1073. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1020-y.

Scherer, M., Blozik, E., Himmel, W., Laptinskaya, D., Kochen, M.M. and Herrmann-Lingen, C. (2008). Psychometric properties of a German version of the neck pain and disability scale. European Spine Journal, [online] 17(7), pp.922–929. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0677-y. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2443271/ [Accessed 15 May 2023].

Smale, S., 2018. Breathing Pattern Disorders – Treatment Approaches. Available at: https://www.raynersmale.com/blog/2018/2/13/breathing-pattern-disorders-treatment-approaches. Accessed on: 14th May 2023.

Stratford, P.W. and Binkley, J.M. (2000). A comparison study of the back pain functional scale and Roland Morris Questionnaire. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. The Journal of Rheumatology, [online] 27(8), pp.1928–1936. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10955335/ [Accessed 17 May 2023].

Tatsios, P.I., Grammatopoulou, E., Dimitriadis, Z., Papandreou, M., Paraskevopoulos, E., Spanos, S., Karakasidou, P. and Koumantakis, G.A. (2022) The Effectiveness of Spinal, Diaphragmatic, and Specific Stabilization Exercise Manual Therapy and Respiratory-Related Interventions in Patients with Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics. Basel 12(7). [Online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9316964/ [Accessed 16/05/2023]

University Hospitals Birmingham., (2023). “Nijmegen Questionnaire” [online] available at https://hgs.uhb.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/Nijmegen_Questionnaire.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2023]

University Hospital Southampton, 2023. Breathing pattern disorders- Information for patients. Available at: https://www.uhs.nhs.uk/Media/UHS-website-2019/Patientinformation/Respiratory/Breathing-pattern-disorders-patient-information.pdf. Accessed on: 14th May 2023.

Youssef, A.S.A., Xia, N., Emara, S.T.E., Moustafa, I.M. and Huang, X. (2019). Addition of a new three-dimensional adjustable cervical thoracic orthosis to a multi-modal program in the treatment of nonspecific neck pain: study protocol for a randomised pilot trial. Trials, [online] 20(1). Pg. 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3337-0. Available at: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-019-3337-0 [Accessed 16 May 2023]