Girdlestone Resection Arthroplasty

Original Editor - Kirsten Coutts

Top Contributors - Kirsten Coutts and Lucinda hampton

History[edit | edit source]

The Girdlestone resection arthroplasty (GRA) was first described by an English Orthopaedic surgeon, Gathorne Robert Girdlestone in 1928. The procedure has been known by his name ever since. It was first used for chronic septic arthritis of the hip, mostly arising from Tuberculosis. As there was not yet good access to antibiotics and arthroplasty, this procedure was used to resect the femoral head, to relieve pain and the source of infection. [1] This procedure continued to be used widely for hip infections and also for complex fractures following gunshot wounds.[2][1]

The techniques used and indications for this surgery have evolved over time.

It is also referred to as : Hip resection arthroplasty, Girdlestone excision arthroplasty of Hip, Girdlestone procedure and Femoral head ostectomy.

Procedure, Indications[edit | edit source]

The first documented surgery of this kind, in 1928, involved radical excision of the femoral head and neck to drain the tuberculous hip. A transverse incision of 5-6 inches (12-15cm) long with its centre near the greater trochanter was made, exposing the gluteal muscles and fascia. All deep tissues, including greater trochanter and the gluteal muscles were removed. A transfer wedge was removed to allow the surgeon access to the joint and surrounding area. All decayed bone and septic debris was removed. The cavity was packed with gauze wicks and rubber drains to ensure drainage and control secondary granulation. The skin flaps were drawn back and stitched into the periosteum to prevent sinus-track from forming, to reduce the pain of dressings and allow covering of the raw areas with excessive granulation. Lastly, a spica splintage was fitted for the patient.

The 3 main goals of this surgery was to remove dead and devitalised tissues, flatten down dead spaces, and allow drainage so the wound would heal from the bottom. [1]

The surgery described above is mostly no longer used thanks to modern medicine, lower tuberculosis prevalence and better infection control measures.[1] It is however still used as a salvage or last resort procedure in many cases such as :

- Patients where mobility is poor - such as non-ambulatory cerebral palsy patients who often have persistent pain and chronic hip dislocation and subluxation . This allows pain relief, improvement of sitting balance and better perineal care. [1]

- Patients where bone or soft tissue coverage is not strong enough to insert a new prosthesis[1]

- Patients with severe comorbidities who are unfit for surgery eg asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease [1][3]

- Patients where infection cannot be controlled[1]

- Patients with cognitive impairments such as Dementia, who may not follow hip advice and precautions post Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) .[3]

- Recurrent hip dislocations/hip prostheses dislocations [3]

- Patients with femoral head osteonecrosis with high surgical and anaesthetic risk factors [4]

- Patients with hip fractures in low-resource developing countries who do not have access to THA and modern surgical techniques. [2]

- Patients with Periacetabular tumors [5]

- Patients with poor post-operative prognosis [3]

THA gained success in the 1960s when it was developed by Sir John Charnley. Since then it has evolved and is now one of the fastest growing orthopaedic procedures worldwide. [6]See Image 3.

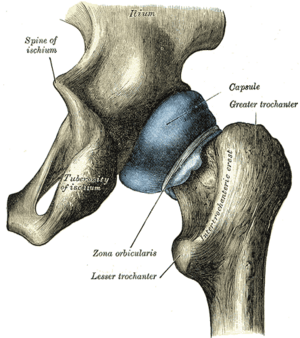

One of the main causes for hip arthroplasty failure leading to Girdlestone resection arthroplasty (GRA) , is prosthetic joint infection (PJI). PJI after THA is an increasing and severe complication.[6] In these cases, the hip prosthesis is removed without replacement. An incision is made though the fascia lata and gluteal muscles, the joint capsule is released and the femoral stem is removed. The bone marrow is cleaned and flushed and the wound is closed with a drain inserted. Various approaches are used by different surgeons, under spinal or general anaesthesia. The posterolateral approach is most commonly used because of the nearly circumferential exposure of the acetabulum and the ability to displace the femoral component. This leaves only a crude articulation between femur and acetabulum. See Image 4. The proximal femur migrates 5-10cm cranially, and finds support at the abductor muscles. It also exorotates due to the shape of the pelvis.[1] The patient is left with a leg length discrepancy (LLD).

The second option available is to use GRA as part of a two-stage revision arthroplasty, whereby a new prosthesis is fitted. This is not a feasible option in many cases, due to many patients with GRA being older and having multiple comorbidities. [6]The average age of GRA is 72 years. [1]In younger and fit for surgery patients, this is proving to show good success rates thanks to advanced antimicrobial therapy. [3]

Outcomes[edit | edit source]

When looking at post-operative outcomes it is important to remember that this surgery is often used as a last resort option. The patients often have to accept some functional limitation, in order to improve their pain and preserve their life when ongoing infection is a serious complication. For this reason studies with high quality evidence such as Randomised controlled trials are lacking.

It has furthermore been documented that the use of standard assessment tools and outcome measures is limited to this surgery as the factors assessed are severely impacted thought the surgical process. For example the Harris Hip score considers factors such as range of motion, LLD and fixed flexion contractures as part of the assessment. This will be inappropriate for assessing GRA which unavoidably reduces muscle bulk, causes LLD and leads to inherent and unavoidable limitations to range of motion. [3]

Basu et al in 2011 undertook a review of the GRA in modern medicine. They looked at 41 cases of GRA, which is a small sample size. The average number of co-morbidities was 3.6 with the most frequent medical condition being Dementia and the average age was 78 years. These two factors resulted in a high mortality rate of 41%. Analysis of 17 patients showed that in all surviving patients, infection had been controlled and wounds had healed. 29% reported no pain and 65% reported adequate pain control. 41% of patients were left with a severe limp whilst 23%reported no limp. All patients were either severely restricted in their walking or required significant support. No patients were able to mobilise without aids although 29% were able to manage stairs. 29% were able to mobilise outside with walking aids. 59% of patients were able to bend to put on their socks and shoes and over 70% of patients were able to sit comfortably in a chair for longer than 5 hours. Despite poor Harris Hip scores, only 29% were unsatisfied with the procedure. The paper demonstrated that the GRA is mostly used for an increasingly elderly population with multiple comorbidities. It confirms the procedure can offer acceptable functional outcomes and remove infection. [3]

A study done by Stephane et al in 2020, looked at 3 cases of destroyed proximal femurs from gunshot wounds, in a conflict zone in DR Congo. The ages of the patients were 18, 32 and 45 years and there were no comorbidities. All 3 patients were severely handicapped, completely reliant on help for Activities of daily living (ADL) and reliant on analgesia. The GRA was chosen due to the lack of infrastructure and resources for prosthetic implant or fracture reconstruction. Additionally there was a high risk of infection after gunshot wounds and destruction of the vascular supply to the femoral head. Patients received daily mobilisation and physiotherapy. Patients were non weight bearing until complete wound healing. They received ongoing Physiotherapy with progressive loading and muscle strengthening. Post op the LLD was 3cm, 3cm and 5cm.All patients received an adjusted unilateral sole elevation on the operated side 3 months post surgery. All patients showed proper wound healing with no signs of infection. Full weight bearing was achieved with 2 patients requiring a walking stick and one needing 2 crutches. Activities of daily living could be carried out independently which the authors felt was the most noteworthy improvement. It concluded that GRA was an effective, reliable and safe treatment option and showed good functional results, particularly in the case of medically underserved areas with lack of prosthetic options.[2]

Other studies agree that the GRA is a valuable option in the management of infected total hip prostheses. Similarly most papers conclude that in select cases, it provides good functional outcomes and is effective in controlling infection and pain. This intervention does come with a high mortality rate and thus should ideally only be used as a last resort. [2][3][1]

Providing sufficient pre-op patient education, giving early intensive physiotherapy, and ensuring timely orthotic input will assist in promoting good post-operative outcomes. [6][2]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

As there are many different indications for this surgery, this will depend on each case. One can expect:

- Hip pain and possible instability

- Hip infection

- Reduced mobility and reliance on walking aids

- Reduced ability to complete activities of daily living (ADL)

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

The Orthopaedic surgeon will carry out a number of tests prior to surgery:

- Hip examination

- X-rays and Magnetic Resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the extent of bone and soft tissue damage and to plan surgery.

- Surgeons will also take a medical history and do a general health check. They will do blood work to check for infection markers, clotting factors and the general health of the patient.

- An anaesthetist will review the patient, paying attention to the cardiac and respiratory systems and suitability for surgery.

Pre-Op[edit | edit source]

The role of the Physiotherapist will start before surgery, firstly doing a pre-operative assessment.This will include:

- Subjective assessment and determining baseline functioning and ability to do ADLs. Obtaining relevant information about the patients home environment and support available on discharge. Talking to family to obtain all relevant information for a smooth discharge.

- Objective assessment including: Range of motion, respiratory assessment, muscle power, neuro-vascular status, circulation, mobility (if able to mobilise) and level of function

Pre-operative Treatment will consist of:

- Advice and education - what the patient can expect after surgery and when the Physiotherapist will see the patient post-operatively and begin to mobilise. Explanation of possible reduced weight bearing status and management of pain prior to this. Realistic goal setting and discharge planning. Explain any restrictions and precautions likely. Explain that a LLD is expected and how to manage this. Explain that various members of the multi-disciplinary team(MDT) will be involved.

- Bed exercises-important to reduce muscle atrophy and start targeting important muscle groups for rehabilitation

- Mobility and transfers- if this is possible prior to surgery

- Deep breathing exercises (DBE) and any respiratory care advice as needed

Post-Op[edit | edit source]

A physiotherapist will begin to mobilise the patient as soon as possible, either on the day of surgery or the following day, once clearance from the Orthopaedic Doctor has been granted and weight bearing status is confirmed. Each rehabilitation protocol will vary depending on the institution and the surgeons preferences.

- Check the patients chest- teach coughing and sputum clearance techniques if necessary. Continue with DBE

- Start with bed exercises to improve muscle strength and improve range of motion. Give the patient instructions to continue this on their own throughout the day. Give home exercises to continue on discharge.

- Teach and assist with transfers and do gait re-education using an appropriate walking aid. The patient will often need to partially weight bear initially so it is important the patient understands this. First assistance will be given, with the goal in mind to make the patient independent with this as soon as possible. Aim to sit in the chair to assist with chest expansion, blood pressure control, pressure relief and working the anti-gravity muscles.

As the patient improves, exercises will be progressed and the distance mobilised will increase. Practising of stairs will be done prior to discharge. Once the patient is independent in all transfers and can mobilise safely and independently, do their daily exercises and has the appropriate support in place at home, he or she can be discharged.

Multi-disciplinary Team[edit | edit source]

There will be various members of the multi-disciplinary team who may be involved post-operatively:

- Orthotist- To fit a shoe raiser or insole to correct the resultant LLD. In patients where the risk of dislocation is high, a hip abduction brace may be fitted. Compliance with this can be poor, especially those with cognitive impairments.

- Occupational therapist (OT) - Will work closely with the physiotherapist to promote independent function and ability to do activities of daily living. The OT will ensure the patient can do all necessary tasks that are essential for the patient to cope and be safe at home. If any equipment is needed, such as a bed rail or toilet raiser, the OT can order this.

- Discharge coordinator- Will ensure a smooth discharge process and coordinate the efforts from various team members. Will ensure any support that is needed is in place prior to discharge. It might also involve organising transport home from hospital.

- Social worker- Can arrange packages of care to be setup in the home for those patients that are not fully independent. This can range from once a day to four times a day, or a full time carer in some cases. It might also involved services that can do shopping for the patient or bring cooked meals. The care provided will vary greatly in different areas of the world.

- Orthopaedic Dr- Will continue to oversee the medical management of the patient and observe for any clinical deterioration. The Dr will check the dressings and monitor for any post operative complications such as a Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) , dislocation and chest infections. The orthopaedic Dr will also advise on rehabilitation protocols and if there can be a change in weight bearing at certain time intervals.

- Pharmacist- Ensures the patient receives the correct medication which is safe to use, especially with older patients with comorbidities . Makes changes to analgesia if needed, especially if limiting rehabilitation. May also need to work with the microbiology team and ensure the right antibiotics are being used to treat the current infection.

- Nurse- The nurses will care for the patient in hospital providing basic care, administering medication and checking and changing wound dressings if needed. In cases where pain is high, it will be helpful to time the session with the Physiotherapist once analgesia has been given.

Communication within the MDT will be vital and will usually involve team meetings on a daily basis to update everyone.

Resources[edit | edit source]

See the below video from Dr Nabil Ebraheim who describes the GRA and explains some of the conditions he finds it useful for.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Vincenten CM, Gosens T, van Susante JC, Somford MP. The Girdlestone situation: a historical essay. Journal of Bone and Joint Infection 2019;4:203-208

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Stephane N, Neuhaus V, Mirosavljev S, Ciritsis B. Is there a role for the Girdlestone resection arthroplasty in modern orthopedic trauma surgery? Case series from a medically underserved region and literature review. Medical Case Reports and Review 2020;3:1-4

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Basu I, Howes M, Jowett C, Levack B. Girdlestones excision arthroplasty: Current update. International Journal of Surgery 2011;9:310-313

- ↑ Than J, Jiganti M, Tedesco N. Simultaneous primary bilateral hip resection arthroplasty . Arthroplasty Today 2021;12:24-28

- ↑ Yong Lee S, Jeon D, Cho W, Song W, Kong C. Comparison of Pasteurized Autograft-Prosthesis Composite Reconstruction and Resection Hip Arthroplasty for Periacetabular Tumors. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery 2017;9:374-385

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Vincenten C, Den Oudsten B, Bos P, Bolder S, Gosens T. Quality of life and health status after Girdlestone resection arthroplasty in patients with an infected total hip prosthesis. Journal of Bone and joint Infection 2019;4:10-15

- ↑ Nabil Ebraheim. Girdlestone Procedure Hip Fractures Elderly - Everything You Need To Know. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lROLU9UT0uo&t=4s [last accessed 25/04/2023]