General Assessment of a Patient with Burns

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Carin Hunter, Tarina van der Stockt, Ahmed M Diab, Kim Jackson and Rucha Gadgil

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Each individual with a burn injury is unique. Management should always be tailored to the individual, their injury and their context. This requires a detailed and accurate initial assessment. Investing time in the initial evaluation helps ensure the best possible immediate care, reduces the risk of long-term complications, and maximises a patient's functional recovery. By conducting a comprehensive assessment, the multidisciplinary team can become familiar with the patient's long-term goals and align therapy to these objectives. This, in turn, enhances patient engagement with the treatment plan.

Sharing initial assessment findings with relevant members of the multidisciplinary team helps to streamline subsequent assessments and facilitates continuity of care, both during rehabilitation and upon transition to community settings. This approach helps to minimise patient frustration and ensures accurate transmission of relevant information throughout the treatment journey.

Goal Setting[edit | edit source]

The multidisciplinary team should set goals using the SMART goal method with each patient. SMART goals are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

Short-term rehabilitation goals might include:[1]

- preventing respiratory complications

- controlling oedema

- maintaining joint range of motion

- maintaining strength

- preventing excessive scarring

Functional long-term goals might include:

- achieving functional independence

- improving participation in society

- maintaining / enhancing psychological well-being

- establishing / achieving a return to work plan

Key Considerations[edit | edit source]

The following sections explore key considerations when evaluating a patient with a burn injury.[1]

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

Patients with burn injuries are at "high risk" because of a number of factors, including:[1]

- injury factors:

- inhalation injury

- burn area

- depth of burn

- scarring

- patient factors

- reduced ambulation and mobility

- increased bed rest

- increased pain

- pre-existing comorbidities

- treatment factors

- skin reconstruction surgery

- invasive monitoring and procedures

- management in critical care

Inhalation Injury[edit | edit source]

During the subjective assessment, clinicians should carefully observe for signs of inhalation injury, especially in cases where there is a history of exposure to fire and smoke within enclosed spaces, coupled with diminished levels of consciousness.[2][3] Physical indicators may include charring around the mouth and nostrils, singed nasal hairs, presence of soot in sputum and upper airways, alterations in voice quality, and the presence of wheezing.[4] If any signs of inhalation injury are noted, a qualified member of staff must conduct an inhalation injury examination. This ensures the prompt initiation of appropriate treatment measures. For more information, please see the Inhalation Assessment section below.

Total Body Surface Area (TBSA)[edit | edit source]

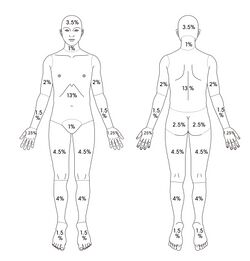

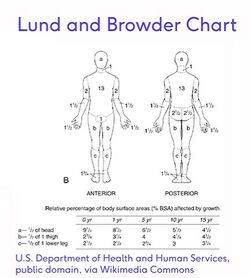

Various methods are used to conduct a Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) assessment, including the Rules of Nines and Lund and Browder methods.

- The Lund and Browder method is considered more accurate than the Rule of Nines.[1] The Lund and Browder takes longer to perform but is very accurate and is applicable for any age burn assessment.

- The Rule of Nines is often used in adults on admission as it is a quick and simple way of assessing for fluid resuscitation. The Rule of Nines CANNOT be used on a child as their head proportion is different from an adult and thus is inaccurate.

- The Palmar Surface Method is also commonly used. This method estimates burn coverage based on the patient's palm size (where each palm represents approximately 1% TBSA).

Please note, you should not include oedema when calculating burn size area.[1]

Important TBSA considerations:

Predicting TBSA is important for fluid resuscitation. The Parkland Formula is still widely used to determine appropriate fluid resuscitation over the first 24 hours.[5]

Parkland Formula = 4 mL/kg/%TBSA (3 mL/kg/%TBSA in children) = total amount of crystalloid fluid during first 24 hours

However, it is important to note that "no formula is comprehensive enough to include the true complexity of burns as there are many unaccounted clinical variables [...but] the Parkland formula is a reasonable starting point for achieving adequate fluid resuscitation despite its limitations."[6]

When a patient's burn injury exceeds 20-25% TBSA, a systemic inflammatory reaction may occur. This impacts multiple organ systems, including the respiratory system.

Please see Burn Wound Assessment for more information on the TBSA Assessment. Please see Systemic Response to Burns for more information on the whole-body response to burn injuries.

Burn Type and Depth[edit | edit source]

It is important to regularly re-examine the extent of tissue destruction as it can change for at least 48 hours post-burn. Burn injuries rarely present uniformly with a single depth throughout the affected area.[7] Early interventions and other patient factors (e.g. age and health) can influence the type and depth of a burn.[2]

Burn Site and Impact[edit | edit source]

The location of a burn injury can significantly impact functional outcomes and the level of trauma experienced by a patient. Burns to certain areas of the body require specialised treatment because of their functional importance and the risk for potential complications. These critical areas include:[1]

- hands

- face

- perineum

- joints

Subjective Assessment for a Patient with a Burn Injury[edit | edit source]

When taking a subjective history, it is essential to consider emotional trauma that may be associated with a burn injury. Consider if it is appropriate to involve family members or witnesses to fill in gaps in the history or to provide additional context.[1]

History of Presenting Complaint[edit | edit source]

- History of the incident[1]

- pay close attention to the events leading up to the injury and the mechanism of injury

- First aid[1]

- document any first aid administered: if the initial first aid seems inadequate, clinicians should consider the possibility of a deeper burn injury

- include details of medications administered on-site, specifying amounts and times given: this information helps prevent adverse reactions and interactions with other medications

- Falls[1]

- is there any indication that the patient fell?

- if yes, what height did they fall from?

- when there is a history of falls, consider the potential for head injury, fractures, sprains, etc

- Electrical injury[1]

- in cases of electrical injuries, what voltage was involved and which parts of the body were in contact with earth?

- in cases where there has been a high voltage current, suspect nerve or deep muscle injury

- Explosions[1]

- often associated with falls, high-velocity injuries

- can also be associated with tympanic membrane injury, which can cause hearing loss and affect communication

- Passage to hospital[1]

- document the mode of transportation and time to admission

Medical and Surgical History[edit | edit source]

Find out about any medical or surgical management:

- what pain medication has been given?

- what procedures so far? Debridement, escharotomy, flaps/grafts, etc

- what instructions are there from the multidisciplinary team?[8]

Past Medical History[edit | edit source]

Find out about:

- general medical history

- previous surgical interventions

- medication: including amount, duration and if conditions are controlled or uncontrolled by medication

Social History[edit | edit source]

In the social history, find out about a patient's pre-injury level of function, including:[1]

- activities of daily living:

- basic activities of daily living: these vary from person to person, but can include dressing, bathing, eating, shopping, driving, home maintenance

- pre-injury physical function: mobility, including stair mobility, lifting ability

- pre-injury physical fitness: strength, flexibility, endurance, balance

- social supports and home situation

- occupation: this is particularly relevant for patients with burns to their hands

Psychosocial Factors / Yellow Flags[edit | edit source]

For individuals with burn injuries, it is important to consider:[1]

- self-image

- coping style

- mental health

- emotional behaviour

Key Aspects of the Objective Assessment of a Patient with a Burn Injury[edit | edit source]

The following sections discuss the key components of the objective assessment for a patient with a burn injury.

Pain Intensity Assessment[edit | edit source]

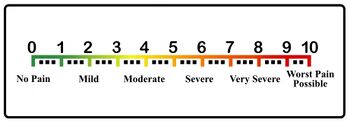

When assessing pain intensity in individuals with burn injuries, various observational behavioural pain assessment scales are utilised, depending on the patient's age:

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)[1]

- suitable for measuring pain in individuals aged 12 and older

- patients are asked to mark their level of pain on a horizontal line, where one end represents no pain, and the other end represents the worst pain imaginable

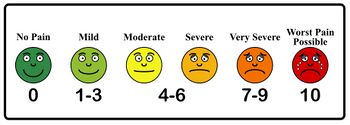

- Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale[1]

- can be used in children aged five years and older

- a self-report measure used to assess the intensity of a child's pain

- consists of six pain assessment cards that show faces with different emotions, from smiling to crying

- Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability (FLACC) scale[9]

- observational pain scale

- widely used in the paediatric population to assess pain in infants and children who are unable to express their pain verbally[10]

- it scores pain intensity by rating five behaviours (face, legs, activity, cry, consolability) on a 0 to 2 scale[10]:

- 0 to 3 = no / light pain

- 4 to 7 = moderate pain

- 8 to 10 = acute pain

- COMFORT Behavior Scale (CBS)

- used to assess pain and distress in intubated and self-ventilating children in paediatric intensive care units[11][12]

- includes six categories, which are scored on a 1 to 5 scale, with a maximum score of 30:

- alertness

- calmness/agitation

- crying

- physical movement

- muscle tone

- facial tension

- higher scores = greater pain / distress

- Pain Observation Scale for Young Children (POCIS)[13]

- used to assess pain in children

- focuses on observing specific behaviours that indicate pain in children, particularly those aged between 1 and 5 years old

- typically has seven items, which represent observable behaviours associated with pain in young children (e.g. facial expressions, movement, crying, etc)

- a pain severity score is given ranging from 0 to 7

- higher scores = greater pain

For more information on Pain Assessment Tools, please see:

- British Pain Society: Outcome Measures

- Physiopedia page: Outcome Measures

Burn Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

When managing patients with burn injuries within a multidisciplinary team, it is beneficial to use outcome measures that can be retested as the condition progresses. Some examples of outcome measures include[14][15]:

- Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief (BSHS-B): evaluates the physical and psychosocial functioning of burn patients and their quality of life[16]

- Burns Scar Index (Vancouver Scar Scale): the first tool to be validated to assess burn scars; it focuses on four indicators (scar height and thickness, pliability, vascularity, and pigmentation)[17]

- Burns Specific Pain Anxiety Scale: evaluates pain-related anxiety in patients with burn injuries[18]

Inhalation Assessment[edit | edit source]

"No consensus exists regarding the diagnosis, grading, and prognosis of inhalation injury [...] Full manifestation occurs up to 48 hours after the inhalation insult once the inflammation reaches its peak. Further, the clinical presentation (degree of respiratory failure) may not correspond with the intensity of the exposure."[19]

Most patients with inhalation injuries who present early to an emergency department will be conscious with patent airways. Their initial chest radiograph and arterial blood gases may "appear at most only slightly abnormal."[19] Because of delayed presentations or non-specific presentations, a number of diagnostic adjuncts are used to diagnose inhalation burn injuries.[19]

Physical findings: please note that physical findings, while valuable, can sometimes be misleading and must be considered alongside other diagnostic tools. Key physical findings include:[19]

- sooty sputum

- stridor (noisy breathing due to an obstructed airway)

- wheezing

- facial burns

- singed nasal / facial hairs

- anxiety

- cough

- stupor

- dyspnoea

- hoarse voice

- oedema

- erythema (superficial reddening of the skin, usually in patches)

- inspiratory and end expiratory crackles on auscultation

- chest x-ray changes

- signs of hypoxia

- headache

- shortness of breath

- fast heartbeat

- coughing

- wheezing

- confusion

- bluish colour in skin, fingernails, and lips

Bronchoscopy assessment:[19]

- fiberoptic (flexible) bronchoscopy (FOB) is the gold standard for diagnosis of an inhalation injury

- it provides an immediate view of the airway

- while not universally available, it is widely used[20]

- signs of inhalation injury on bronchoscopy may include:[19]

- erythema

- oedema (which may be seen as a blunting of the carina)

- mucosal blisters

- erosions

- haemorrhages

- bronchial secretions

- soot deposits

- indirect laryngoscopy can serve as an alternative when bronchoscopy is unavailable, offering visualisation as far as the vocal cords

Key determinants of inhalation injury severity include:[19]

- duration of exposure to smoke

- temperature of the inhaled smoke

- smoke composition

For more information on inhalation injuries, please see:

- A Critical Update of the Assessment and Acute Management of Patients with Severe Burns[21]

- Inhalation Injury in the Burned Patient[19]

Oedema Assessment[edit | edit source]

A comprehensive oedema assessment has subjective and objective components. As part of the subjective history, remember to note when the swelling began and if there are changes in oedema with position changes. Care must be taken with the objective assessment to help minimise infection risk and avoid any increase in pain. Clinicians will ideally understand how to assess oedema by stage and by size.

| Stage of oedema | Appearance of oedema |

| Stage 1 | Soft, may pit on pressure |

| Stage 2 | Firm, rubbery, non-pitting |

| Stage 3 | Hard, fibrosed |

Commonly used tools to measure oedema include:

- volume measurements (e.g. using a water volumeter)

- girth measurements (e.g. using a tape measure).

- pitting oedema assessment (based on the depth and duration of the indentation)

For more information on these measurements, please see Oedema Assessment.

Physical Assessment[edit | edit source]

When conducting a physical assessment, it can be helpful to divide the evaluation into two parts: 1) assessing the upper and lower limbs and trunk and 2) assessing general functional mobility. Clinicians should consider factors that may impact healing / recovery, such as prolonged bed rest, high levels of pain, and pre-existing comorbidities.[1][8][2]

Limbs and Trunk Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Assess:

- Limiting factors can include:

- pain

- muscle length

- trans-articular burns

- scar contracture

- individual specificity of the burn

General Functional Mobility Assessment[edit | edit source]

- The mobility assessment should only be completed once the patient is medically stable. This assessment should focus on:

- preventing complications associated with prolonged bed rest

- restoring functional independence

- Assess:

- Factors to consider during the mobility assessment:

- posture

- activities of daily living

- demands of vocational roles

- cardiovascular response to mobilisation

- neurological status

- concomitant injuries / weight-bearing status

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Hale A, O’Donovan R, Diskin S, McEvoy S, Keohane C, Gormley G. Impairment and Disability Short Course. Physiotherapy in Burns, Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery, 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Siemionow MZ, Eisenmann-Klein M, editors. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Springer Science & Business Media; 2010 Jan 13.

- ↑ Charles WN, Collins D, Mandalia S, Matwala K, Dutt A, Tatlock J, Singh S. Impact of inhalation injury on outcomes in critically ill burns patients: 12-year experience at a regional burns centre. Burns. 2022 Sep;48(6):1386-95.

- ↑ Wise B, Levine Z. Inhalation injury. Can Fam Physician. 2015 Jan;61(1):47-9.

- ↑ Daniels M, Fuchs PC, Lefering R, Grigutsch D, Seyhan H, Limper U, et al. Is the Parkland formula still the best method for determining the fluid resuscitation volume in adults for the first 24 hours after injury? - A retrospective analysis of burn patients in Germany. Burns. 2021 Jun;47(4):914-21.

- ↑ Mehta M, Tudor GJ. Parkland Formula. [Updated 2023 Jun 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537190/

- ↑ Martin H. Immediate management of burn injury. 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hettiaratchy S, Papini R. Initial management of a major burn: II--assessment and resuscitation. BMJ. 2004;329(7457):101-103.

- ↑ Feng Z, Tang Q, Lin J, He Q, Peng C. Application of animated cartoons in reducing the pain of dressing changes in children with burn injuries. International journal of burns and trauma. 2018;8(5):106.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Crellin DJ, Harrison D, Santamaria N, Babl FE. Systematic review of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability scale for assessing pain in infants and children. PAIN. 2015 Nov;156(11):2132–51.

- ↑ Boerlage AA, Ista E, Duivenvoorden HJ, de Wildt SN, Tibboel D, van Dijk M. The COMFORT behaviour scale detects clinically meaningful effects of analgesic and sedative treatment. Eur J Pain. 2015 Apr;19(4):473-9.

- ↑ Suprawoto DN, Nurhaeni N, Waluyanti FT. COMFORT Behavior Scale instrument: validity and reliability test for critically ill pediatric patients in Indonesia. Pediatr Rep. 2020 Jun 25;12(Suppl 1):8690.

- ↑ Voelker R. Diagnosing Pediatric Pain. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1713.

- ↑ Taal LA, Faber AW, Van Loey NE, Reynders CL, Hofland HW. The abbreviated burn specific pain anxiety scale: a multicenter study. Burns. 1999 Sep 1;25(6):493-7.

- ↑ Taal LA, Faber AW. The burn specific pain anxiety scale: introduction of a reliable and valid measure. Burns. 1997 Mar 1;23(2):147-50.

- ↑ Tyack Z, Simons M, Spinks A, Wasiak J. A systematic review of the quality of burn scar rating scales for clinical and research use. Burns. 2012 Feb 1;38(1):6-18.

- ↑ Nguyen TA, Feldstein SI, Shumaker PR, Krakowski AC. A review of scar assessment scales. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015 Mar;34(1):28-36.

- ↑ Taal LA, Faber AW. The burn specific pain anxiety scale: introduction of a reliable and valid measure. Burns. 1997 Mar;23(2):147-50.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 Foncerrada G, Culnan DM, Capek KD, González-Trejo S, Cambiaso-Daniel J, Woodson LC, Herndon DN, Finnerty CC, Lee JO. Inhalation injury in the burned patient. Annals of plastic surgery. 2018 Mar;80(3 Suppl 2):S98.

- ↑ Long B, Graybill JC, Rosenberg H. Just the facts: evaluation and management of thermal burns. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021 Nov 2:1-3.

- ↑ Lang TC, Zhao R, Kim A, Wijewardena A, Vandervord J, Xue M, Jackson CJ. A critical update of the assessment and acute management of patients with severe burns. Advances in wound care. 2019 Dec 1;8(12):607-33.