The Role of the Physiotherapist in Learning Disabilities

Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Learning Disabilities[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1992 defined a learning disability as ‘‘a condition of arrested or incomplete development of the mind, which is especially characterized by impairment of skills manifested during the developmental period, which contribute to the overall level of intelligence, i.e., cognitive, language, motor, and social abilities’’.[1] However, this definition is outdated and implied the term ‘mental retardation’ which is deemed very offensive by many people today.

The current definition of a learning disability is defined by Valuing People, the 2001 White Paper report on the health and social care of people with learning disabilities.[2]

“A learning disability includes the presence of:

- a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills (impaired intelligence), with;

- a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning);

- which started before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development.”

The terms used to describe a person with a learning disability has been changing since the 1970s, from people with mental sub-normality to mental handicap to eventually learning disability in the 1990s. In other countries such as the United States (US), the terms ‘intellectual disability’ and ‘mental retardation’ are used instead. Do note that in the US, the term learning disability is used to describe specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia, dyspraxia and dyscalculia.

Internationally, three criteria have to be met before a learning disability can be identified or diagnosed[3]:

- Intellectual impairment (IQ<70);

- Social or adaptive dysfunction combined with IQ; and

- Early onset.

Watch the video below to know more about the meaning of learning disabilities[4]:

Learning Disability Compared to Learning Difficulty[edit | edit source]

As mentioned earlier, different terminologies are used in different countries. It is important not to confuse learning disability with learning difficulty.[5] In the UK, specific learning difficulties refers to conditions such as dyslexia, dyspraxia/developmental coordination disorder, dyscalculia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Dyslexia is a difficulty that affects 10% of the population. It affects the way a person processes information, thus they may have difficulty with memory, organisation and sequencing.[6]

- Dyspraxia is a disorder that affects fine and gross motor skills in children and adults.[6]

- Dyscalculia is a difficulty understanding maths concepts and symbols.[6]

- ADHD is a disorder that affects attention. A person with ADHD may be restless, inattentive, impulsive, erratic and have inappropriate, unpredictable behaviour. They may appear unintentionally aggressive.[6]

Specific learning difficulties affect the way information is learned and processed. It is a neurological condition rather than a psychological condition and it does not affect intelligence. A student may be diagnosed with a learning difficulty if there is a big gap between achievement and ability or there is lack of achievement for age and ability.

Prevalence and Demographics of Learning Disabilities[edit | edit source]

Global: One-fifth of the estimated global total population (110-190 million people) experience significant disabilities. Globally, one in 160 children has an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). 1991 prevalence estimates for children seven to ten years old are that two in 1000 children are identified with cerebral palsy and four in 1000 with moderate to profound intellectual disability (IQ<50).[7]

Europe: In the European Union (15 countries), 1.1 to 1.5 million people have a severe learning disabilities and 2.3 to 2.7 million people have a mild learning disability.[8]

United Kingdom: 1.5 million people in the UK are thought to have a learning disability.[5]

England: In 2011, it was estimated that there were 1,191,000 people have learning disabilities. This includes 905,00 adults with learning disabilities, of whom, 189,000 were known to learning disability services.[9]

Wales: In 2008-2009, 4,493 health checks were carried out in Wales, findings shown that 41% of the estimated 11,046 people aged 16 years and it is estimated that 43% of people aged 18 years and over and have a learning disability.[10]

Northern Ireland: In 2009, it was reported that there were 27,000 people in Northern Ireland with a learning disability.[11]

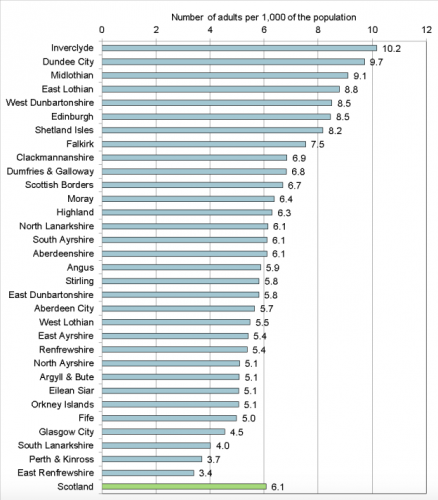

Scotland: In 2015, Collection of Learning Disabilities Statistics Scotland data was carried out by the ScotXed Team within the Scottish Government. This aimed to increase standardisation and improve the quality of the data. In 2015, there were 27,218 adults with learning disabilities known to local authorities. This equates to 6.1 people with learning disabilities per 1,000 adults in the general population. 4,617 adults were identified as being on the autism spectrum. 70% of these adults had a learning disability.[12] Figure 2.1 below represents the number of adults known to each local authority.

Different Levels of Learning Disability[edit | edit source]

The term ‘learning disability’ is a very broad description for this group of individuals, with the threshold set at an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) of below 70 in the United Kingdom (UK). As such, terms such as profound, severe, moderate and mild are used in the UK to describe the different severity and levels of need which these individuals may have.

Profound: Individuals with an IQ score under 20, with severely limited understanding. They have difficulty communicating, require support with mobility and may need support with their behaviour. They may have multiple disabilities such as visual impairments, hearing impairments and difficulty with movement. They may also have extensive health needs, epilepsy and autism.[3]

Severe: Individuals with an IQ score of 20-35. They often use basic words and gestures to communicate their needs. They may need a high level of support with activities of daily living. Some may have additional medical needs and require more support with mobility.[3]

Moderate: Individuals with an IQ score of 35-50. They are able to communicate their day-to-day needs and wishes. They may need some assistance and guidance with their personal care and may require longer time to learn new skills.[3]

Mild: Individuals with an IQ score of 50-70. They are able to hold a conversation and communicate their needs effectively. They are often independent in caring for themselves and have basic reading and writing skills. They may require support to understand complex ideas.[3]

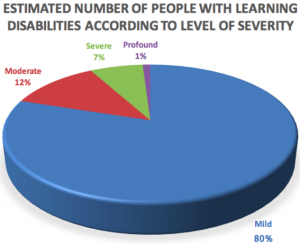

Figure 2.2 below illustrates the number of people with learning disabilities according to level of severity:[13]

Factors Resulting in Learning Disability[edit | edit source]

According to the British Institute for Learning Disabilities in 2011, these are key factors of learning disability:[3]

Chromosomal conditions: Chromosomes make up the genetic blueprint for humans. Everyone has 46 chromosomes in their cells. Abnormality in their chromosomes can result in a learning disability. Such conditions include Down’s Syndrome, Fragile-X syndrome, Williams Syndrome, Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome and Prader-Willi Syndrome.[14]

Maternal factors: Infections such as Cytomegalovirus and Toxoplasmosis, factors such as diet deficiencies and excessive alcohol consumption during pregnancy can cause learning disability in the unborn child.[15][16]

Metabolic disorders: A person’s metabolism controls all the chemical reactions in the body. Certain conditions affecting metabolism can result in a learning disability. For example, Phenylketonuria is a disorder that increases the levels of a substance called Phenylalanine in the blood. Phenylalanine is an amino acid which is normally obtained through the diet. If untreated the abnormally high levels of phenylalanine can cause severe learning disabilities.[17]

Events during birth: A learning disability can occur if a baby’s oxygen supply is disrupted during labour, if a child is born extremely premature or becomes very ill after birth.

Events after birth: Some childhood infections such as encephalitis and meningitis can cause learning disabilities. A severe head injury can also cause a learning disability.

Impact of Learning Disability on the Person[edit | edit source]

There is a wide spectrum of orthopaedic problems with learning disability, some as a result of the underlying condition and others due to accidents. Individuals with learning disability are exposed to higher risk of injuries more than the general population.

It has been shown in Denmark, US and Australia that adults with learning disability are at higher risk of death compared to general public.[18] These include deaths from accidents, falls, burns, drug toxicity and choking.[19] Finlayson et al. carried out a study to investigate injuries in 511 adults affected by LD in the UK for 12 months and the result showed that they were twice likely to get injured more than others; with falls found to be the most common reason of injury (accounting 55% of all injuries).[18]

In addition, people with learning disability are slower in learning certain skills than others and therefore need more assistance in several aspects of their lives. This is influenced by the severity of the disability which varies from mild to profound[20] as mentioned above.

Researches have indicated the increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders among people with learning disabilities compared to general population. According to WHO, the prevalence of psychiatric and behavioural disorders is at least three times greater in people with learning disability in comparison to unaffected population.[21] These disorders include:

- Affective (mood) disorders: depressive episodes, recurrent depressive disorder, cyclothymia, manic episodes, bipolar affective disorders and persistent mood disorder.

- Anxiety, stress related disorders: phobic anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders.

- Stress related disorders: The people affected with learning disability are more vulnerable to physical, sexual and emotional abuse, therefore more likely to complain of stress-related disorders.

- Personality disorders: The prevalence of diagnosed personality disorders in learning disability individuals has varied from 22% to 92%, showing that majority of the learning disability population are presenting with personality disorders such as paranoia, schizoid, antisocial, anxious and dependent personality disorders.

- Dementia: The prevalence of people with Down Syndrome is in the same level as the general population over the age of 65 but in Down Syndrome, dementia appears in earlier age. This explains the impact of learning disability on occurrence of dementia.[21]

Health Risks[edit | edit source]

- Coronary heart disease is a leading cause of death in people with learning disabilities (14-20%).

- Respiratory disease is much higher in people with learning disabilities and is thought to be leading cause of death (46-52%).

- The prevalence of dementia is much higher in people with learning disabilities compared to the general population.

- Epilepsy is thought to be 20 times higher in people with learning disabilities. Uncontrolled epilepsy can have a negative effect on a person’s quality of life and mortality.

- Sensory impairments: people with learning disabilities are 8-200 times more likely to have a vision impairment and 40% are reported to have a hearing impairment compared to the general population.

- Physical impairments: Adults who are non-mobile have an increased mortality rate than if they were mobile. A study in the Netherlands reported that people with learning disabilities are 14 times more likely to have a musculoskeletal condition.

- People with learning disabilities are also at an increased risk of oral health problems, dysphagia, diabetes, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, constipation and endocrine disorders.[22]

- Personal health risks:

- <10% of adults in supported living eat a balanced diet.

- >80% of adults with learning disabilities engage in levels of physical activity below the Department of Healths minimum recommendation.

- People with learning disabilities are more likely to be either underweight or overweight/obese.[22]

Obstacles Within Health System[edit | edit source]

People with learning disabilities have poorer health than people without disabilities, and to an extent, this is avoidable. People with learning disabilities face inequalities from early life, and this includes barriers in accessing timely, appropriate and effective health care.

People with learning disabilities have an increased risk of early death compared to the general population. The causes of mortality in people with moderate to severe learning disabilities is three times higher than the general population.[23]

A range of organisational barriers to accessing healthcare services have been identified, these include:

- Lack of services

- Physical barriers

- Failure by healthcare professional to make adjustments for people with regard to literacy and communication difficulties

- ‘Diagnostic overshadowing’ – where symptoms of physical ill health are mistaken or attributed to a person’s behavioural problem

- Negative attitude of healthcare staff towards people with learning disabilities.[22]

Role of the Physiotherapist[edit | edit source]

Mainstream or Specialist Physiotherapy Services[edit | edit source]

In the past, it was standard practice for people with learning disabilities to be referred on to specialist services. This placed a lot of demand on the specialist services. In recent years, this has changed and we are now encouraging those with learning disabilities to use mainstream services.[24] This is a result of changes in the Department of Health policies, which aims to "ensure that people with learning disabilities, including those from minority ethnic communities, have the same right of access to mainstream health services as the rest of the population" . When we use the term ‘mainstream’ services, we are referring to what would be classed as services which are used regularly and can be used by the general population.

In order to be referred on to specialist services, a person must have been diagnosed with a learning disability, which as has been previously stated is defined as having a reduced ability to understand new or complex information or learn new skills, a reduced ability to cope independently, and the condition started before adulthood with a lasting effect on the individual's development.[25] If a person is known to have a learning disability, they will be referred on to a specialist learning disability team. Once the team receives the referral, they will make a decision on whether the person requires specialist input or if they can be put into the mainstream system.[26]

It is possible for patients with a learning disability to be seen by a mainstream physiotherapist, depending on the severity their condition affects them, as long as reasonable adjustments are made. If a mainstream physiotherapist treats a patient with a learning disability, they can liaise with the specialist physiotherapist if they need any support to ensure the patient receives the best care.[26]

Physiotherapy Assessment[edit | edit source]

As already mentioned in the previous section, those with learning disabilities tend to have difficulty with communication. This can make carrying out subjective and objective assessments difficult and may feel daunting to those who are not used to dealing with a patient who has a learning disability. Before the patient has even arrived for their appointment, you need to make sure you prepare if you know before hand that the patient you are seeing has a learning disability. The ACPPLD [27]created a document (figure 3.1) that is aimed at helping mainstream physiotherapists treating patients with learning disabilities.

Points to be taken into consideration are:

- Preparation before the appointment is key so try to find out in advance about the patient's history and health plan.

- When planning the appointment, the individual's comfort, accessibility and ability need to be understood.

- Consent needs to be gained before commencing the assessment.

- For the most part, the subjective and objective assessments are similar to what would be provided to the general population, however, some adjustments will need to be made to suit the individual needs of the patient. As such, it is important that you have a sound understanding of all the fundamental components of an assessment.

- During the assessment, make sure to use short and simple sentences and always be checking their understanding of what you are saying.[28]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

The main aims of physiotherapy management and intervention are as follows:

- Assess the needs of the patient and carers

- Maintain good general health of the patient

- Prevent or minimise contractures and prevent fixed positional deformities occurring

- Maximize the patient’s functional movement, ability and independence

- Share knowledge with the patient, carers and family members [29]

As previously mentioned, some of the conditions that come under the term ‘learning disability’ have a physical impact on the individual. This impact can vary greatly and so care needs to be tailored. An awareness of any physical, sensory and/ or communication problems a person has is essential to ensure effective treatment.[29]

The physiotherapist will be able to deal with musculoskeletal, neurological and respiratory issues that may be specifically related to an individual’s condition or something that is completely unrelated. For example, if a patient has a purely musculoskeletal issue that is not due to their condition, a musculoskeletal physiotherapist, may be more suited to treat them. However, if a person has quite demanding communication and care needs, as well as other comorbidities, it may be more appropriate for the specialist physiotherapist to treat them, but they could still have some input from a physiotherapist specialising in the area that concerns the issue.

As with the assessment, many of the skills used in treatment is similar to what the general population will receive, however, a different approach can be taken to help support the individual as well as ensuring their needs are being met.[29]

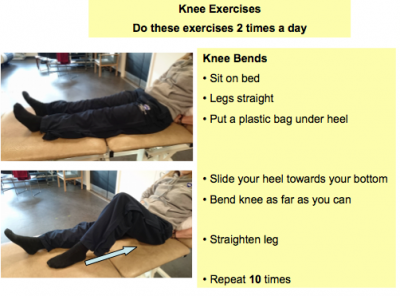

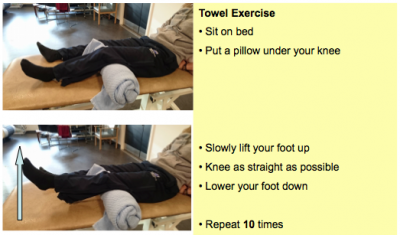

If providing exercise sheets, it can help to have pictures along with simple language.[30] Photographing the patient doing the exercises themselves and putting this on the sheet can sometimes be of benefit as they recognise themselves and are therefore more likely to do the exercises. See figures 3.3 and 3.4 below for examples of exercise sheets including text and photographs.

NHS Shetland provide an Adult Learning Disability Physiotherapy Service Guide. This gives an overview of interventions and outcomes depending on the functional ability of an individual.

Rebound Therapy[edit | edit source]

Rebound therapy is the therapeutic use of trampolines. It is currently used with people with a wide range of abilities including those with a mild physical and learning disability, to those with multiple and profound learning disabilities.[31][32]

Benefits:

- Raise low tone or lower increased tone

- Increase body part awareness, spatial awareness, proprioception and sensory awareness

- Promote relaxation

- Challenges balance to help improve dynamic balance issues

- Increase vocalisation in those with reduced vocal ability, creating a gateway to communication sometimes giving squeals of delight

- Gasps and intakes of breath can also stimulate the cough reflex [32]

As with any physiotherapy intervention, there are contraindications that need to be considered before any treatment can occur.

The Rebound Therapy Association for Chartered Physiotherapists (RTACP) has produced guidelines on rebound therapy and states 3 absolute contraindications consisting of:

- Cranio-vertebral Instability: including Atlanto-Axial Instability (AAI) and Atlanto-Occipital Instability (AOI). AAI is a condition experienced by 10-20% of people with Down’s Syndrome and occurs due to weakened ligaments causing slack joints.[33]

- Detaching retina

- Pregnancy

For more information on promoting safe practice with Rebound therapy, please read the RTACP guidelines.

Hydrotherapy[edit | edit source]

Hydrotherapy is a treatment which takes place in heated water using its buoyancy and thermal properties to provide postural support and reduce load on unstable joints.[34]

Benefits:

- Help relieve pain

- Promote relaxation

- Improve cardiorespiratory system

- Provide resistance to help strengthen muscles

- Improve confidence and promote independence [34][35]

Contraindications:

- Acute vomiting and diarrhea

- Skin conditions or infections

- Hypotension or hypertension

- Cardiac conditions

- Decreased vital capacity

- Uncontrolled epilepsy

- Fear of water

Care should be taken if a person has:

24-hour Postural Care[edit | edit source]

People who are physically able can adjust and correct their position and posture if they become uncomfortable, however, some people with learning disabilities, especially those with profound and multiple disabilities, may not be able to do so. They may be physically incapable of moving themselves and not be able to communicate their discomfort. As a result, they tend to end up in a poor position which can have adverse effects on their health. These effects include pain, contractures, spinal deformities (such as scoliosis), an increased risk of fractures, loss of function, breathing difficulties and an increased likelihood of surgery.[37][38]

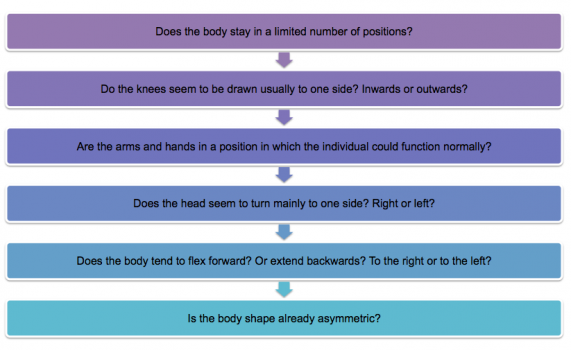

As physiotherapists, we can use postural care to prevent poor positioning. Postural care aims to protect and restore body shape by using appropriate equipment and positioning techniques.[39]When considering postural care as part of treatment, an assessment tool, called the Mansfield Checklist of Need for Postural Care, can be used to identify whether there is a need for postural care. [40]

The checklist consists of the following questions:

If you answer yes to any of these questions, the individual may benefit from postural care.

Additional information should be written to describe the patient’s position and also explain how this may impact the patient.

Following the assessment of body symmetry, equipment such as wheelchairs, specialised seating, orthotics and sleep systems can be used to maintain a good position over a full 24 hour period.[41][37][38]

Please watch this short video which gives a brief explanation of what postural care is.

[42]

As posture care needs to be provided essentially 24 hours a day, families and carers will often need to help with maintaining a good position. This requires them to be well educated and trained in the proper technique. Physiotherapists can help provide this by involving family members and/or carers in appointments so that they can practice in a setting where support is provided.

Falls Prevention[edit | edit source]

There is a high incidence of falls and injuries in those with learning disabilities making it a serious problem. Injuries in those with a learning disability are twice as likely to occur, compared to the general population, and they are 6-8 times more likely to die as a result. 25% to 40% of people with learning disabilities experience at least one fall (with or without injury) a year, with approximately one-third of falls reported to result in injury.[43]

A Falls Pathway Service was set up by a Community Learning Disabilities Physiotherapy Team in Glasgow. An evaluation of the service [44] was carried out and showed that there was an improvement in both gait and balance, with a reduction in the number of falls.

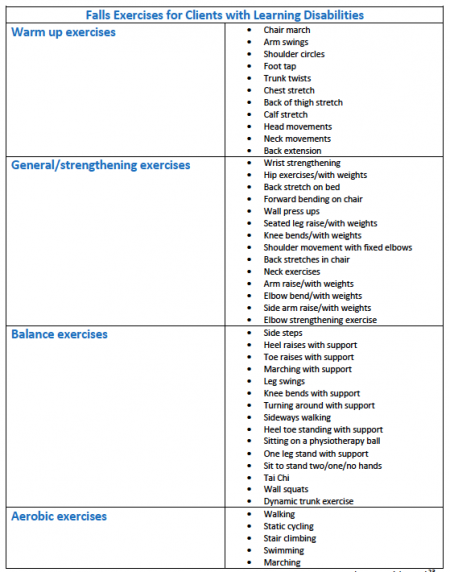

The Falls Pathway Service is a 12-week home-based exercise programme. Figure 3.5 below shows a list of exercises a physiotherapist can choose from.[43][44]

The programme involves individuals with learning disabilities completing 2–3 exercises from each section: warm up, general/strengthening, and balance every day for 12 weeks; plus 2–3 aerobic exercises per week for 12 weeks. The exercises are selected by the physiotherapist suited to the individual’s needs.

By following this pathway, physiotherapists are:

- Promoting and providing increased opportunities for weight bearing to reduce the risk of osteoporosis

- Helping to rebuild confidence and overcome fears of falling/causing injury

- Promoting physical activity and exercise[44]

Physical Activity Promotion[edit | edit source]

What can you do to promote health in those with a learning disability?

Promoting health enables people to take control and be responsible for improving their own health. It extends beyond the focus on individual behaviour, towards a variety of social and environmental interventions.[45]

With the two leading causes of death being respiratory and coronary heart disease respectively[22], Physical activity needs to be promoted in these individuals.

Those with a learning disability are less likely to participate in physical activity due to:

- Poor motor coordination

- Poor balance

- Inability to perform multiple tasks simultaneously

- Short attention span

- Hyperactivity

- Poor lifestyle orientations

- Poor self-esteem

- Inability to handle a situation[46]

People with learning disabilities are already at risk of developing numerous conditions and being sedentary will only increase this risk. As physiotherapists, we should be getting people with learning disabilities to engage in physical activity where possible.

Effects of physical activity

Engaging in physical activity has shown to:

- Improve lung capacity

- Reduce resting heart rates and blood pressure

- Decrease body fat mass

- Increase lean body mass and muscle strength

- Maintain bone mass and reduce trauma-induced fractures by carrying out weight-bearing activities

- Reduce depression and anxiety levels and improve self-image, mental health and social skills [46]

Education[edit | edit source]

Another large part of a physiotherapist’s role is educating all those involved in a person care to help manage their long-term conditions.[29]In order to do this, the individual, their family members and/or carers need to have a good level of health literacy so they understand what information they are receiving, but also so they can give informed consent and make decisions.

Educating everyone involved in an individual’s care as to what their different health needs are aims to improve their understanding of the condition and why we are making specific decisions in relation to the treatment approach.

Summary[edit | edit source]

The following video is a Physio Natters podcast focusing on learning disabilities. A physiotherapist, who works as a specialist with the community learning disability team in Fife, is the guest speaker. The podcast covers information about the role a physiotherapist plays and gives some helpful advice on what to do should you have a patient with a learning disability. It summarises some of the information discussed in this section so will hopefully help to reinforce your learning. It may also be a better option if you are an aural/auditory learner.

[47]

Whilst also providing some advice on how adjustments can be made so that physiotherapists in the mainstream services can help treat those with a learning disability. It has briefly touched on some of the complications that arise from those with learning disabilities having issues surrounding communication and health literacy. With that in mind, the following sections will explore the concepts of communication and health literacy in more detail, and also give advice on tools and strategies that physiotherapists can implement to overcome some of the barriers caused by these issues.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ World health organization. Chapter V. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online2004/fr-icd.htm?gf70.htm+ (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Department of health. Valuing people, a new strategy for learning disability for the 21st century. London: Department of Health, 2001. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/250877/5086.pdf (accessed 3 Jan 2017).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 BILD. Factsheet: learning disabilities. www.bild.org.uk/EasySiteWeb/GatewayLink.aspx?alId=2522 (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Mencap. What does learning disability really mean? [Video] 2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yvZYyeWE20 (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Emerson E, et al. People with learning disabilities in England 2011, 2011. http://boltonshealthmatters.org/sites/default/files/IHAL2012-04PWLD2011.pdf (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 The British Dyslexia Association. What are specific learning difficulties? http://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/educator/what-are-specific-learning-difficulties (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Collaborative on health and the environment. Learning and developmental disabilities research and resources. https://www.healthandenvironment.org/what-we-know/health-diseases-and-disabilities/learning-and-developmental-disabilities-research-and-resources (accessed 17 Jan 2017).

- ↑ European Intellectual Disability Research Network 2003. Intellectual disability in Europe. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2003. http://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Intellectual-Disability-in-Europe.pdf (accessed 12 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Emerson E, et al. People with learning disabilities in England 2011, 2011. http://boltonshealthmatters.org/sites/default/files/IHAL2012-04PWLD2011.pdf (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Public health wales. Monitoring the public health impact of health checks for adults with a learning disability in Wales. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/Documents/256/Health_Checks_Final_Report_March_2010.pdf (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Department of health, social services and public safety. Delivering the bamford vision. https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/dhssps/bamford-action-plan-2009-2011.pdf (accessed 3 Jan 2017).

- ↑ SCLD. A national statistics publication for Scotland key findings. Edinburgh: SCLD; 2016.

- ↑ Holt G, Bouras N. Health in learning disabilities: a training pack for staff working with people who have dual diagnosis of mental health needs and learning disabilities. 2nd ed. Brighton: Pavilion Publishing, 1997.

- ↑ Learn genetics. Chromosomal abnormalities. http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/disorders/chromosomal/ (accessed 20 Dec 2016).

- ↑ Center for disease control and prevention. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and congenital CMV infection. https://www.cdc.gov/cmv/congenital-infection.html (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- ↑ NHS Choices. Toxoplasmosis - symptoms. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Toxoplasmosis/Pages/Symptoms.aspx (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- ↑ Genetics Home Reference. Phenylketonuria. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/phenylketonuria (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Finlayson J, Morrison J, Skelton DA, Ballinger C, Mantry D, Jackson A, Cooper S-A. The circumstances and impact of injuries on adults with learning disabilities. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014 Aug 15;77(8):400–9.

- ↑ Durvasula S, Beange H, Baker W. Mortality of people with intellectual disability in northern sydney. Journal of intellectual and developmental disability. 2002; 27(4):255-264. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1366825021000029311 (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- ↑ Foundation for people with learning disabilities. Learning disability statistics. https://www.learningdisabilities.org.uk/learning-disabilities/help-information/learning-disability-statistics-/187687- (accessed 7 September 2022).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Rennie J. Learning disability: Physical therapy treatment and management. A collaborative Approach edition. 2nd ed. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Emerson E, Baines S. Health inequalities & people with learning disabilities in the UK: 2010. https://www.improvinghealthandlives.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_7479_IHaL2010-3HealthInequality2010.pdf (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Tyrer F, McGrother C. Cause-specific mortality and death certificate reporting in adults with moderate to profound intellectual disability. Journal of intellectual disability research. 2009;53(11):898–904. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19694898 (accessed 13 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Hodges C. Getting to grips with learning disabilities. Frontline 2005; 11(12). http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/getting-grips-learning-disabilities (accessed 20 Dec 2016).

- ↑ NHS Fife. Community LD Team Online Client Referral Form. https://www.nhsfife.org/nhs/index.cfm?fuseaction=nhs.pagedisplay&p2sid=DC302A78-FCE1-C2E8-E9AEC0BB86CA2738&themeid=3B984BF2-65BF-00F7-D42941481355468F (accessed 21 Dec 2016).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Cole A. Into the mainstream: physio access for those with learning disabilities. Frontline 2016; 22(11). http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/mainstream-physio-access-those-learning-disabilities (accessed 15 Dec 2016).

- ↑ ACPPLD. So your next patient has a learning disability. ACPPLD. 2016. http://acppld.csp.org.uk/documents/so-your-next-patient-has-learning-disability (accessed 21 Sept 2016).

- ↑ The National Autistic Society. Communicating and interacting. http://www.autism.org.uk/about/communication/communicating.aspx (accessed 3 January 2017).

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Findlay A, An Approach to Treating and Managing Severe Physical Disability. In: Rennie, J editor. Learning disability: Physical Therapy Treatment and Management - A Collaborative Approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p200 - 214.

- ↑ Mencap. Communicating with people with a learning disability, 2016. https://www.mencap.org.uk/learning-disability-explained/communicating-people-learning-disability (accessed 20 December 2016).

- ↑ Rebound Therapy Association for Chartered Physiotherapists. Safe Practice in Rebound Therapy. http://acppld.csp.org.uk/documents/safe-practice-rebound-therapy (accessed 20 December 2016).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Smith S, Cook D, Rebound Therapy. In: Rennie, J editor. Learning disability: Physical Therapy Treatment and Management - A Collaborative Approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p249 - 262.

- ↑ Ali FE, Al-Bustan MA, Al-Busairi WA, Al-Mulla FA, Esbaita EY. Cervical spine abnormalities associated with Down syndrome. International Orthopaedics 2006; 30(4): 284-289. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2532127/ (accessed 20 January 2017).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Jorgić B, Dimitrijević L, Lambeck J, Aleksandrović M, Okičić T, Madić D. Effects of aquatic programs in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: systematic review. Sport science 2012; 5(2): 49-56. https://www.sposci.com/PDFS/BR0502/SVEE/04%20CL%2009%20BJ.pdf (accessed 19 December 2016).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Auty PO, Hydrotherapy. In: Rennie, J editor. Learning disability: Physical Therapy Treatment and Management - A Collaborative Approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p215 - 231.

- ↑ Davis BC, Harrison RA. Hydrotherapy in Practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1988.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Millet R. Body works: postural care for people with profound learning disabilities. Frontline 2015; 21(12). http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/body-work-postural-care-people-profound-learning-disabilities (accessed 21 Dec 2016).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Mencap. Raising our Sights how-to guide 4 health, 2010. https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-06/2012.340%20Raising%20our%20sights_Guide%20to%20health_FINAL.pdf (accessed 21 Dec 2016).

- ↑ Goldsmith J, Goldsmith L, Postural Care. In: Rennie, J editor. Learning disability: Physical Therapy Treatment and Management - A Collaborative Approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p179 - 199.

- ↑ Postural Care CIC. The Mansfield Checklist. http://www.simplestuffworks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/The-Mansfield-Checklist.pdf (accessed 5 January 2017).

- ↑ ACPPLD. Learning disability physiotherapy. http://acppld.csp.org.uk/learning-disabilities-physiotherapy (accessed 21 Sept 2016).

- ↑ Mencap. Postural care: What is postural care? [Video] 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXZjm1tbs-0 (accessed 4 Jan 2017).

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Glasgow Caledonian University. Injury and Fall Prevention for People with Learning Disabilities. 2016. http://acppld.csp.org.uk/documents/injury-fall-prevention-people-learning-disabilities (accessed 20 Dec 2016).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Crockett J, Finlayson J, Skelton DA, Miller G. Promoting Exercise as Part of a Physiotherapy-Led Falls Pathway Service for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A Service Evaluation. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2015; 28(3): 257-264. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25179503 (accessed 22 Dec 2016).

- ↑ World Health Organization. Health Promotion. http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/ (accessed 3 January 2017).

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Kumari PP, Raj P. Role of Physical Activity in Learning Disability: A Review. Clinical and Experimental Psychology 2016; 2 (Suppl 1). https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/role-of-physical-activity-in-learning-disability-a-review-2471-2701-1000118.pdf (accessed 3 Jan 2017).

- ↑ The Physio Matters Podcast. Physio Natters! Session 6 - Learning Disabilities - Andrew Lee, Jack March & Rob Tyer [Video] 2016. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aDmN5CI7wt8 (accessed 23 Dec 2016).