Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)

Original Editors - Chelsey Walker, Jacqueline Keller, Katie Schwarz, Jenny Nordin, Chris Slininger as part of the Texas State University Evidence-based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Chelsey Walker, Xiomara Hernandez, Chris Slininger, Jacqueline Keller, Celien Van den Meerssche, Vanwymeersch Celine, Admin, Katie Schwarz, Laura Ritchie, Jenny Nordin, Fasuba Ayobami, Yves Hubar, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Kai A. Sigel, Scott Buxton, Momina Khalid, Alicia Fernandes, Wendy Walker, Claire Knott, Wanda van Niekerk and Aminat Abolade

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

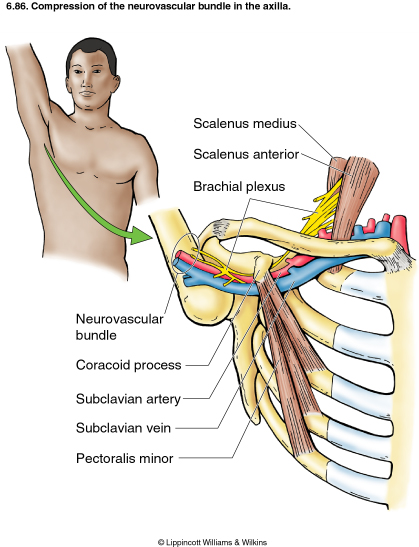

- The term ‘thoracic outlet syndrome’ describes compression of the neurovascular structures as they exit through the thoracic outlet (cervicothoracobrachial region).

- The thoracic outlet is marked by the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly, the middle scalene posteriorly, and the first rib inferiorly.[1] [2]

- This condition has emerged as one of the most controversial topics in musculoskeletal medicine and rehabilitation[3].

- The term ‘TOS’ does not specify the structure being compressed. Investigators, namely, identify two main categories of TOS:

- The vascular form (arterial or venous), which raises few diagnostic problems,

- The neurological form, which occurs in more than 95-99% of all cases of TOS,

Therefore, the syndrome should be differentiated by using the terms arterial TOS (ATOS), venous TOS (VTOS), or neurogenic (NTOS).[1][2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

- The first narrowing area is the most proximal and is named the interscalene triangle: This triangle is bordered by the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly, the middle scalene muscle posteriorly, and the medial surface of the first rib inferiorly.

The presence of the scalene minimus muscle and the fact that both the anterior and middle scalene muscles have their insertion in the first rib (which can cause overlapping) can cause a narrow space and therefore compression. The brachial plexus and the subclavian artery pass through this space.

- The second passageway is called the costoclavicular triangle, which is bordered anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, posteromedially by the first rib, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula. The subclavian vein, artery, and plexus brachialis cross this costoclavicular region and then further enter the subcoracoïd space. Just distal to the insterscalene triangle. Compression of these structures can occur as a result of congenital abnormalities, trauma to the first rib or clavicle, and structural changes in the subclavian muscle or the costocoracoid ligament.

- The last passageway is called the subcoracoid or sub-pectoralis minor space: This last passageway is beneath the coracoid process, just under the pectoralis minor tendon. The borders of the thoraco-coraco-pectoral space include the coracoid process superiorly, the pect minor anteriorly, and ribs 2-4 posteriorly. Shortening of the Pectoralis Major can lead to a narrowing of this last space and therefore compression of the neurovascular structures during hyperabduction.[2][4][5]

- Certain anatomical abnormalities can potentially compromise the thoracic outlet as well. These include:

- the presence of a cervical rib,

- congenital soft tissue abnormalities,

- clavicular hypomobility [3], and

- functionally acquired anatomical changes[4].

- Soft tissue abnormalities may create compression or tension loading of the neurovascular structures found within the thoracic outlet (such as hypertrophy, a broader middle scalene attachment on the 1st rib, or fibrous bands that increase stiffness).

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

- TOS affects approximately 8% of the population

- its is 3-4 times as frequent in women as in men between the ages of 20 and 50. Females have less-developed muscles, a greater tendency for drooping shoulders owing to additional breast tissue, a narrowed thoracic outlet, and an anatomical lower sternum. These factors change the angle between the scalene muscles and consequently cause a higher prevalence in women.[4][5][6]

- The mean age of people effected by TOS is 30–40;

- it is rarely seen in children. Almost all cases of TOS (95–98%) affect the brachial plexus; the other 2–5% affect vascular structures, such as the subclavian artery and vein.

There are several factors that can cause TOS:

- Cervical ribs are present in approximately 0.5-0.6% of the population, 50-80% of which are bilateral, and 10–20% produce symptoms; the female to male ratio is 2:1.

- Cervical ribs and the fibromuscular bands connected to them are the cause of most neural compression.[7]

Fibrous bands are a more common cause of TOS than rib anomalies.

Congenital Factors:[edit | edit source]

- Cervical rib[8][9][10]

- Prolonged transverse process

- Anomalous muscles

- Fibrous anomalies (transversocostal, costocostal)

- Abnormalities of the insertion of the scalene muscles[8]

- Fibrous muscular bands[8]

- Exostosis of the first rib

- Cervicodorsal scoliosis[11]

- Congenital unilateral- or bilateral elevated scapula

- Location of the A. or V. Subclavian in relation to the M. scalene anterior

Acquired Conditions:[edit | edit source]

- Postural factors

- Dropped shoulder condition[8]

- Wrong work posture (standing or sitting without paying attention to the physiological curvature of the spine)

- Trauma[11]

- Clavicle fracture[8]

- Rib fracture[8]

- Hyperextension neck injury, whiplash[9][12]

- Repetitive stress injuries (repetitive injury most often form sitting at a keyboard for long hours.)[12]

Muscular Causes:[edit | edit source]

- Hypertrophy of the scalene muscles

- Decrease of the tonus of the M. trapezius, M. levator scapulae, M.rhomboids

- Shortening of the scalene muscles, M. trapezius, M. levator scapulae, pectoral muscles

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome vary from patient to patient due to the location of the nerve and/or vessel involvement. Symptoms range from mild pain and sensory changes to limb-threatening complications in severe cases.

- Patients with thoracic outlet syndrome will most likely present pain anywhere between the neck, face, and occipital region or into the chest, shoulder, and upper extremity, and paresthesia in the upper extremity.

- The patient may also complain of altered or absent sensation, weakness, fatigue, or a feeling of heaviness in the arm and hand.

- The skin can also be blotchy or discoloured. A different temperature can also be observed.

- Signs and symptoms are typically worse when the arm is abducted overhead and externally rotated with the head rotated to the same or opposite side. As a result, activities such as overhead throwing, serving a tennis ball, painting a ceiling, driving, or typing may exacerbate symptoms.[13][14]

- When the upper plexus (C5,6,7) is involved, there is a pain in the side of the neck, and this pain may radiate to the ear and face. Often, the pain radiates from the ear posteriorly to the rhomboids and anteriorly over the clavicle and pectoralis regions. The pain may move laterally down the radial nerve area. Headaches are not uncommon when the upper plexus is involved.

- Patients with lower plexus (C8, T1) involvement typically have symptoms that are present in the anterior and posterior shoulder regions and radiate down the ulnar side of the forearm into the hand, the ring, and small fingers.[3][5]

There are four categories of thoracic outlet syndrome, and each presents with unique signs and symptoms (see Table 1). Typically, TOS does not follow a dermatomal or myotomal pattern unless there is nerve root involvement, which will be important in determining your PT diagnosis and planning your treatment [3][4].

| Arterial TOS | Venous TOS | True TOS | Disputed Neurogenic TOS |

|

|

|

|

Compressors : a patient that experiences symptoms throughout the day, while using prolonged postures resulting in increased tension or compression of the thoracic outlet. The most common aggravating postures are head forward with the shoulder girdles protracted and depressed, or activities that involve working overhead with the arms elevated. These positions cause an increase in tension/compression (such as working overhead with elevated arms) that would result in an increase in tension or compression of the neurovascular bundle of the brachial plexus

Releasers: Describes patients who often experience paraesthesia at night that often wakes them up. It is caused by a release of tension or compression to the thoracic outlet, that restores the perineural blood supply to the brachial plexus, signaling a return of normal sensation. This is used as an indicator of a favorable outcome and resolution of symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due to its variability, TOS can be difficult to distinguish from other pathologies with similar presentations. A thorough history and evaluation must be done to determine if the patient’s symptoms are truly TOS. The following pathologies are the common differential diagnoses for TOS[15][16] :

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- De Quervain’s tenosynovitis

- Lateral epicondylitis

- Medial epicondylitis

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS I or II).

- Horner’s Syndrome

- Raynaud’s disease

- Cervical disease (especially discogenic)

- Brachial plexus trauma

- Systemic disorders: inflammatory disease, oesophageal or cardiac disease

- Upper extremity deep venous thrombosis (UEDVT), Paget-Schroetter syndrome

- Rotator cuff pathology

- Glenohumeral joint instability

- Nerve root involvement

- Shoulder Instability

- Malignancies (local tumors)

- Chest pain, angina

- Vasculitis

- Thoracic (T4) syndrome

- Sympathetic-mediated pain

Systematic causes of brachial plexus pain include:

- Pancoast’s Syndrome

- Radiation induced brachial plexopathy

- Parsonage Turner Syndrome[3][4]

There are conditions that can coexist with TOS. It is important to identify these conditions because they should be treated separately. These associated conditions include:

- carpal tunnel syndrome

- peripheral neuropathies (like ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow, shoulder tendinitis and impingement syndrome)

- fibromyalgia of the shoulder and neck muscles

- cervical disc disease (like cervical spondylosis and herniated cervical disk)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- DASH (Disability of Arm Shoulder and Hand)

- SPADI (Shoulder Pain And Disability Index)

- NPRS (Numeric Pain Rating Scale)

- McGill Pain Questionnaire

Diagnostic Procedures [edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of TOS is essentially based on history, physical examination, and provocative tests. I needed ,ultrasound, radiological evaluation, and electrodiagnostic evaluation. It must always be kept in mind that TOS diagnosis is usually confirmed by the elimination of other causes with similar clinical presentation. Especially differential diagnosis of cervical radiculopathies and upper extremity entrapment neuropathies can be hard (McGillicuddy 2004).[2][17] In order to diagnose accurately, the clinical presentation must be evaluated as either neurogenic (compression of the brachial plexus) or vascular (compression of the subclavian vessels). TOS manifestations are varied, and there is no single definitive test, which makes it difficult to diagnose.[5][13]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The following includes common examination findings seen with TOS that should be evaluated; however, this is not an all-inclusive list, and examination should be individualized to the patient.

History[18][edit | edit source]

Make sure to take a thorough history, clear any red flags, and ask the patient how signs and symptoms have affected his/her function.

- Types of symptoms

- Location and amplitude of symptoms

- Irritability of symptoms

- Onset and development over time

- Aggravating/alleviating factors

- Disability

Physical Examination[6][18][edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

- Temperature changes

- Supraclavicular fossa

- Scalene muscles (tenderness)

- Trapezius muscle (tenderness)

Neurological Screen[edit | edit source]

MMT & Flexibility of following muscles:

- Scalene

- Pectoralis major/minor

- Levator scapulae

- Sternocleidomastoid

- Serratus anterior

Special Tests[3][6][edit | edit source]

- Elevated Arm Stress/ Roos test.[5]

- Adson's.[5]

- Wright's.[5]

- Cyriax Release: the patient is seated or standing. The examiner stands behind the patient and grasps under the forearms, holding the elbows at 80 degrees of flexion with the forearms and wrists in neutral. The examiner leans the patient’s trunk posteriorly and passively elevated the shoulder girdle. This position is held for up to 3 minutes. The test is positive when paresthesia and/or numbness (release phenomenon) occurs, including reproduction of symptoms.

- Supraclavicular Pressure: the patient is seated with the arms at the side. The examiner places his fingers on the upper trapezius and thumb on the anterior scalene muscle near the first rib. Then the examiner squeezes the fingers and thumb together for 30 seconds. If there is a reproduction of pain or paresthesia the test is positive, this addresses compromise to brachial plexus through scalene triangles.[3]

- Costoclavicular Maneuver: this test may be used for both neurological and vascular compromise. The patient brings his shoulders posteriorly and hyperflexes his chin. A decrease in symptoms means that the test is positive and that he neurogenic component of the neurovascular bundle is compressed.[5]

- Upper Limb Tension

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion: The test is performed with the patient in sitting. The cervical spine is passively and maximally rotated away from the side being tested. While maintaining this position, the spine is gently flexed as far as possible moving the ear toward the chest. A test is considered positive when the lateral flexion movement is blocked.

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR- |

| Elevated Arm Stress | 52-84% | 30-100% | 1.2-5.2 | 0.4-0.53 |

| Adson's | 79% | 74-100% | 3.29 | 0.28 |

|

Wright's |

70-90% | 29-53% | 1.27-1.49 | 0.34-0.57 |

| Cyriax Release | NT | 77-97% | NA | NA |

| Supraclavicular Pressure | NT | 85-98% | NA | NA |

| Costoclavicular Maneuver | NT | 53-100% | NA | NA |

| Upper Limb Tension | 90% | 38% | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion | 100% | NT | NA | NA |

Electrodiagnostic evaluation and imaging[edit | edit source]

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography are often helpful as components of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected TOS. Nerve conduction studies usually reveal decreased ulnar sensorial potentials, decreased median action potentials, and normal or close to normal ulnar motor and median sensorial potentials. Vascular TOS can be identified with venography and arteriography.

Besides the electrophysiological studies, imaging studies can provide useful information in the diagnosis of TOS. Cervical spine and chest x-rays are important in the identification of bony abnormalities (such as cervical ribs or “peaked C7 transverse processes)

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. Journal Of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. June 2010;18(2):74-83.

Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. June 2010;18(3):132-138.

Resources[edit | edit source]

NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

In summary, thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) involves compression of nerves and blood vessels in the thoracic outlet, leading to various symptoms. It's complex and controversial, with anatomical and acquired factors contributing to its development. Diagnosis involves history, examination, and tests, with treatment ranging from physical therapy to surgery. Ongoing research aims to improve understanding and management of this condition.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 1

This presentation was created by Walt Lingerfelt, Fellow in training at Evidence in Motion. Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 1 / View the presentation |

|

Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 2

This presentation was created by Walt Lingerfelt, Fellow in training at Evidence in Motion. Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 2 / View the presentation |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Laulan J, Fouquet B, Rodaix C, Jauffret P, Roquelaure Y, Descatha A. Thoracic outlet syndrome: definition, aetiological factors, diagnosis, management and occupational impact. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2011 Sep 1;21(3):366-73.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Köknel TG. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Agri: Agri (Algoloji) Dernegi'nin Yayin organidir= The journal of the Turkish Society of Algology. 2005 Apr;17(2):5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Hooper TL, Denton J, McGalliard MK, Brismée JM, Sizer PS. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2010 Jun 1;18(2):74-83.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Laulan J, Fouquet B, Rodaix C, Jauffret P, Roquelaure Y, Descatha A. Thoracic outlet syndrome: definition, aetiological factors, diagnosis, management and occupational impact. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2011 Sep 1;21(3):366-73.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 César Fernàndez et al.; Manual Therapy for Musculoskeletal Pain Syndromes; Elsevier, 2016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Lindgren KA. Thoracic outlet syndrome. International Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2010 Mar 1;32(1):17-24.

- ↑ Boezaart AP, Haller A, Laduzenski S, Koyyalamudi VB, Ihnatsenka B, Wright T. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. International journal of shoulder surgery. 2010 Apr;4(2):27.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Atasoy E. Thoracic outlet syndrome: anatomy. Hand clinics. 2004 Feb 1;20(1):7-14.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sanders RJ, Hammond SL, Rao NM. Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of vascular surgery. 2007 Sep 1;46(3):601-4.

- ↑ Urschel HC. Transaxillary first rib resection for thoracic outlet syndrome. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2005 Dec 1;10(4):313-7.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hamm M. Impact of massage therapy in the treatment of linked pathologies: Scoliosis, costovertebral dysfunction, and thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of Bodywork and movement therapies. 2006 Jan 1;10(1):12-20.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Andrew K Chang, MD et al.; Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in Emergency Medicine; Medscape, Mar 04, 2014

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sandra J. Shultz et al.; Examination of Musculoskeletal Injuries; Human kinetics, 2010

- ↑ Robert A. Donatelli; Physical therapy of the Shoulder; Churchill Livingstone, 1991

- ↑ Watson LA, Pizzari T, Balster S. Thoracic outlet syndrome part 1: clinical manifestations, differentiation and treatment pathways. Manual therapy. 2009 Dec 1;14(6):586-95.

- ↑ Buckley L, Schub E. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. October 2010; Accessed November 2,2011

- ↑ Gillard J, Pérez-Cousin M, Hachulla É, Remy J, Hurtevent JF, Vinckier L, Thévenon A, Duquesnoy B. Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome: contribution of provocative tests, ultrasonography, electrophysiology, and helical computed tomography in 48 patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2001 Oct 1;68(5):416-24.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Vanti C, Natalini L, Romeo A, Tosarelli D, Pillastrini P. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. Eura medicophys. 2007 Mar 1;43:55-70.