Stroke: Physiotherapy Treatment Approaches: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

== State of the Evidence == | == State of the Evidence == | ||

The past decade has seen an exponential growth in the number of Randomised Control Trials in relation to physiotherapy interventions utilised in Stroke. Veerbeek et al (2014) highlight that the number of RCTs on Stroke Interventions has almost quadrupled in the past 10 years, with strong evidence seen in 30 out of 53 interventions for beneficial effects on one or more outcomes. They suggest the main change lies in the increased number of interventions to which ‘strong evidence’ could be assigned and an increase in the number of outcomes for which the findings are statistically significant. <ref name="JM 2014" /><br> | |||

Higher intensity of practice appears to be an important aspect of effective physical therapy and suggestion is that intensity of practice is a key factor in meaningful training after stroke, and that more practice is better. 17 hours of therapy over a 10 week period has been found to be necessary for significant positive effects at both the body function level as well as activities and participation level of the ICF. Yet despite the fact that National Clinical Guidelines advocate for at least 45 mins of therapy daily as long as there are rehabilitation goals and the patient tolerates this intensity, and recognition that high-intensity practice is better there still remains a big contrast between the recommended and actual applied therapy time. Recent surveys in the Netherlands showthat patients with stroke admitted to a hospital stroke unit only received a mean of 22 minutes of physical therapy on weekdays. Similarly, in the United Kingdom inpatients received 30.6 minutes physical therapy per day. Both of these significantly fall short of the recommended 45 mins daily. <ref name="JM 2014" /> | |||

While the body of knowledge in relation to physiotherapy in stroke rehabilitation is still growing further confirmation of the evidence for physiotherapy after stroke, and facilitating the transfer to clinical practice, requires a better understanding of the neurophysiological mechanisms, including neuroplasticity, that drive stroke recovery, as well as the impact of physiotherapy interventions on these underlying mechanisms. Similarily further research is required to support physiotherapy implementation strategies in order to optimize the transfer of scientific knowledge into clinical practice. | |||

High growth in evidence does in its own way create challenges for physiotherapists in keeping up to date with new evidence as it becomes available and there is a need for further investigation into more effective and efficient methods for physiotherapists to keep their knowledge and skill level up-to-date in the long term.<ref name="JM 2014" /> | |||

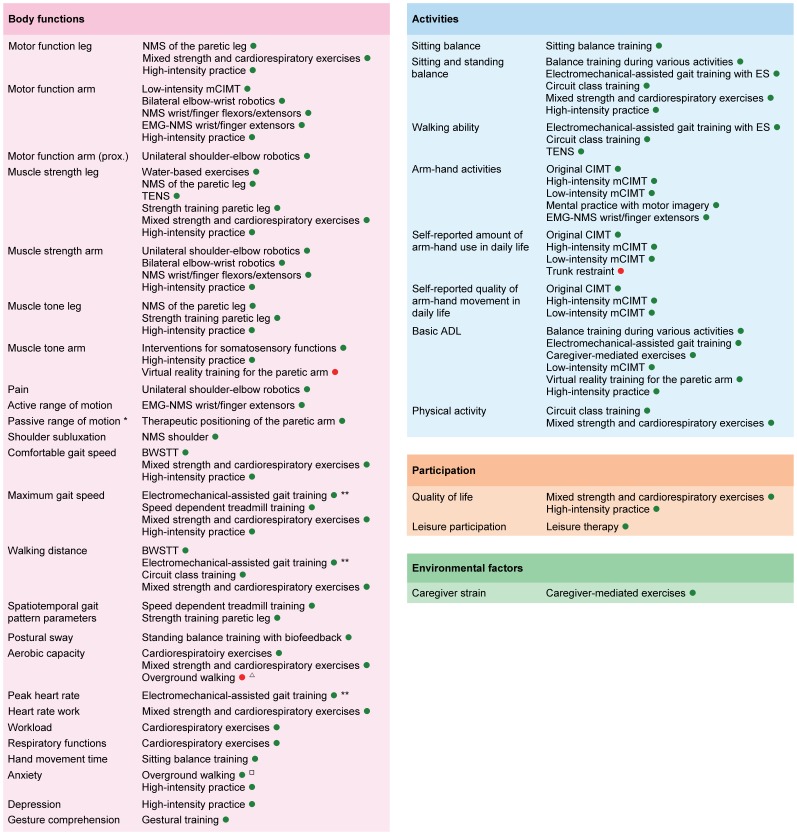

The following Fig.1 graphically displays therange of outcomes classified according to the ICF, with corresponding interventions for which is strong evidence that they significantly affect those outcomes. It should be noted that the clinical applicability of some interventions like electromechanical-assisted gait training and robot-assisted arm training is questionable, due to the accompanying high costs of the equipment. For these interventions, there are often alternative ‘strong evidence’ interventions available. <ref name="JM 2014" /> | |||

[[Image:Stroke Outcome.jpg|left|Overview of Outcomes for which Interventions are available with Significant Summarized Effects. Legend: A green point indicates that the intervention has a significant positive effect on the outcome, while a red point indicates that the intervention has a significant negative effect on the outcome;]] | [[Image:Stroke Outcome.jpg|left|Overview of Outcomes for which Interventions are available with Significant Summarized Effects. Legend: A green point indicates that the intervention has a significant positive effect on the outcome, while a red point indicates that the intervention has a significant negative effect on the outcome;]] | ||

| Line 14: | Line 24: | ||

'''''Figure 1. Overview of Outcomes for which Interventions are available with Significant Summarized Effects'''<br>'' | '''''Figure 1. Overview of Outcomes for which Interventions are available with Significant Summarized Effects'''<br>'' | ||

''This graphically displays the outcomes classified according to the ICF, with corresponding interventions for which is strong evidence that they significantly affect those outcomes.Legend: A green point indicates that the intervention has a significant positive effect on the outcome, while a red point indicates that the intervention has a significant negative effect on the outcome; <ref name="JM 2014">Veerbeek JM, van Wegen E, van Peppen R, van der Wees PJ, Hendriks E, Rietberg M, Kwakkel G. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014 Feb 4;9(2):e87987.</ref>''<br> | ''This graphically displays the outcomes classified according to the ICF, with corresponding interventions for which is strong evidence that they significantly affect those outcomes. Legend: A green point indicates that the intervention has a significant positive effect on the outcome, while a red point indicates that the intervention has a significant negative effect on the outcome; <ref name="JM 2014">Veerbeek JM, van Wegen E, van Peppen R, van der Wees PJ, Hendriks E, Rietberg M, Kwakkel G. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014 Feb 4;9(2):e87987.</ref>''<br> | ||

== Interventions == | == Interventions == | ||

Revision as of 22:43, 21 May 2017

Original Editor - Naomi O'Reilly

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lauren Lopez, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Shaimaa Eldib, Rucha Gadgil and Amrita Patro

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A wide range of treatment techniques and approaches from different philisophical backgrounds are utilised in Neurological Rehabilitation. Research to support the different approaches varies hugely, with a wealth of research to support the use of some techniques while other approaches have limited evidence to support its use but rely on ancedotal evidence. This page provides a brief overview of some of the approaches used in Stroke Rehabilitation with evidence based clinical guideline recommendations.

State of the Evidence[edit | edit source]

The past decade has seen an exponential growth in the number of Randomised Control Trials in relation to physiotherapy interventions utilised in Stroke. Veerbeek et al (2014) highlight that the number of RCTs on Stroke Interventions has almost quadrupled in the past 10 years, with strong evidence seen in 30 out of 53 interventions for beneficial effects on one or more outcomes. They suggest the main change lies in the increased number of interventions to which ‘strong evidence’ could be assigned and an increase in the number of outcomes for which the findings are statistically significant. [1]

Higher intensity of practice appears to be an important aspect of effective physical therapy and suggestion is that intensity of practice is a key factor in meaningful training after stroke, and that more practice is better. 17 hours of therapy over a 10 week period has been found to be necessary for significant positive effects at both the body function level as well as activities and participation level of the ICF. Yet despite the fact that National Clinical Guidelines advocate for at least 45 mins of therapy daily as long as there are rehabilitation goals and the patient tolerates this intensity, and recognition that high-intensity practice is better there still remains a big contrast between the recommended and actual applied therapy time. Recent surveys in the Netherlands showthat patients with stroke admitted to a hospital stroke unit only received a mean of 22 minutes of physical therapy on weekdays. Similarly, in the United Kingdom inpatients received 30.6 minutes physical therapy per day. Both of these significantly fall short of the recommended 45 mins daily. [1]

While the body of knowledge in relation to physiotherapy in stroke rehabilitation is still growing further confirmation of the evidence for physiotherapy after stroke, and facilitating the transfer to clinical practice, requires a better understanding of the neurophysiological mechanisms, including neuroplasticity, that drive stroke recovery, as well as the impact of physiotherapy interventions on these underlying mechanisms. Similarily further research is required to support physiotherapy implementation strategies in order to optimize the transfer of scientific knowledge into clinical practice.

High growth in evidence does in its own way create challenges for physiotherapists in keeping up to date with new evidence as it becomes available and there is a need for further investigation into more effective and efficient methods for physiotherapists to keep their knowledge and skill level up-to-date in the long term.[1]

The following Fig.1 graphically displays therange of outcomes classified according to the ICF, with corresponding interventions for which is strong evidence that they significantly affect those outcomes. It should be noted that the clinical applicability of some interventions like electromechanical-assisted gait training and robot-assisted arm training is questionable, due to the accompanying high costs of the equipment. For these interventions, there are often alternative ‘strong evidence’ interventions available. [1]

Figure 1. Overview of Outcomes for which Interventions are available with Significant Summarized Effects

This graphically displays the outcomes classified according to the ICF, with corresponding interventions for which is strong evidence that they significantly affect those outcomes. Legend: A green point indicates that the intervention has a significant positive effect on the outcome, while a red point indicates that the intervention has a significant negative effect on the outcome; [1]

Interventions [edit | edit source]

Positioning[edit | edit source]

Ability to change position and posture is affected in many individuals post stroke as a result of varying degrees of physical impairments. Therapeutic positioning aims to reduce skin damage, limb swelling, shoulder pain or subluxation, and discomfort, and maximise function and maintain soft tissue length. It is also suggested that positioning may assist in reduction of respiratory complications and avoid compromising hydration and nutrition.

Practice Statement

Consensus-based Recommendation

- Initial specialist assessment for positioning should occur in acute stroke as soon as possible and where possible within 4 hours of arrival at hospital.

- Arm Support devices such as a Lap Tray may be used to assist with arm positioning for those at risk ofshoulder subluxation

- Education and training around correct manual handling and positioning should be provided to the individual with stroke, their family/carer and health professionals, particularly nursing and other allied health staff.Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title- Elevation of the limb when resting should be considered for individuals who are immobile to prevent swelling in the hand and foot. [2]

Early Mobilisation[edit | edit source]

Immobility is associated with a number of post stroke complications such as deep vein thrombosis etc. Early mobilization aims to reduce the time that elapses between stroke and the first time the patient leaves the bed, increasing the amount of physical activity that the patient engages in outside of bed. There remains some ongoing discssion about the exact meaning of very early mobilization but Verbeek et al (2014) define early mobilization as ‘mobilizing a patient out of bed within 24 hours after the stroke, and encouraging them to practice outside the bed'. [3] [4]

Strong Recommendation AGAINST

- Starting intensive out of bed activities within 24 hours of stroke onset is not recommended. Mobilisation within 24 hours of onset should only be for patients who require little or no assistance to mobilise. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleStrong Recommendation FOR

- Commence mobilisation (out of bed activity) within 24 - 48 hrs of stroke onset unless receiving palliative care.Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Balance[edit | edit source]

Sitting[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

- Practising reaching beyond arm’s length while sitting with supervision/assistance should be undertaken for individuals who have difficulty with sitting.

Standing[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

Practice of standing balance should be provided for individuals who have difficulty with standing. Strategies could include:

Gait[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

Tailored repetitive practice of walking (or components of walking) should be practiced as often as possible for individuals with difficulty walking. The following modalities can be used to achieve this:Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

- Circuit Class Therapy (with a focus on overground walking practice) [8]

- Treadmill Training with or without body weight support [9]

- Virtual Reality Training [10] [11]

Weak Recommendation

Other interventions may be used in addition to those above:

Treadmill[edit | edit source]

Electromechanical Assisted[edit | edit source]

Rhythmic Cueing[edit | edit source]

Virtual Reality[edit | edit source]

Overground Walking[edit | edit source]

Community Walking[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation

- Individualised goals should be set and assistance with adaptive equipment, information, and further referral on to other agencies should be provided for individuals who have difficulty with outdoor mobility in the community.

- Walking practice may benefit some individuals and if provided, should occur in a variety of community settings and environments, and may also incorporate virtual reality training that mimics community walking. [16] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Orthotics[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation

Upper Limb[edit | edit source]

Bilateral Arm Training[edit | edit source]

Bilateral Arm Training provides intensive training of bilateral coordination to enable practice of bimanual skills. This approach was developed in response to identified limitations of Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) which precludes the opportunity to practice bilateral skills particularly functional activities that are inherently bimanual. Unilateral and bilateral training are similarly effective. However, intervention success may depend on severity of upper limb paresis and time of intervention post-stroke.

Weak Recommendation

Constraint Induced Movement Therapy[edit | edit source]

Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) involves intensive targeted practice with the affected limb while restraining the non-affected limb, which means that during task-specific practice, individuals with hemiplegic stroke are forced to use their affected limb. Following a neurological incident, often the affected arm and hand are not used sufficiently even if there is some functional activity present. To address this ‘Learned non-use’, the approach of CIMT was developed whereby the non-affected limb was constrained hereby forcing the affected limb to work. This forced-use therapy combined with shaping and goal-directed training is now commonly known as CIMT. [21] [22]

Different categories of CIMT can be distinguished for use in Stroke depending on the duration of the immobilization of the paretic arm and the intensity of task-specific practice: [1]

Original CIMT Applied for 2 to 3 weeks consisting of immobilization of the non-paretic arm with a padded mitt for 90% of waking hours utilising task-oriented training with a high number of repetitions for 6 hours a day; and behavioral strategies to improve both compliance and transfer of the activities practiced from the clinical setting to the patient’s home environment.

High-intensity mCIMT Consists of immobilization of the non-paretic arm with a padded mitt for 90% of waking hours with between 3 to 6 hours of task-oriented training a day. Found to be more beneficial in the acute stage pf rehabilitation with less effect on chronic upper limb impairment.

Low-intensity mCIMT Consisted of immobilization of the non-paretic arm with a padded mitt for > 0% to < 90% of waking hours with between 0 to 3 hours of task-oriented training a day.

Strong Recommendations

- Intensive Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (minimum 2 hours of active therapy per day for 2 weeks, plus restraint for at least 6 hours a day) should be provided to improve arm and hand use for individuals with some active wrist and finger extension. [23] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title- Trunk restraint may also be incorporated into the active therapy sessions at any stage post-stroke. [24] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Electrical Stimulation[edit | edit source]

Functional Electrical Stimulationappears to moderately improve upper limb activity compared with both no intervention and training alone. These findings suggest that FES should be used in stroke rehabilitation to improve the ability to perform functional upper limb activities.

Strong Recommendation

- Use of electrical stimulation in conjunction with motor training should be used to improve upper limb function after stroke . [25] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Robot Assisted Arm Training[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

- Mechanically assisted arm training (e.g. robotics) should be used to improve upper limb function in indivduals with mild to severe arm weakness after stroke. (Mehrholz et al 2015 [156])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Virtual Reality[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

- Virtual Reality and interactive games should be used to improve upper limb function in individuals with mild to moderate arm impairment after stroke. Virtual reality therapy should be provided for at least 15 hours total therapy time. (Laver et al 2015 [96])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Mirror Therapy[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation

- Mirror Therapy may be used as an adjunct to routine therapy to improve arm function after stroke for individuals with mild to moderate weakness, complex regional pain syndrome and/or neglect. (Thieme et al 2012 [162])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Mental Practice[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation

- Mental practice in conjunction with active motor training may be used to improve arm function for individuals with mild to moderate weakness of their arm,. (Kho et al 2014 [157]; Barclay-Goddard et al 2011 [158]; Braun et al 2014 [128])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Splinting[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation AGAINST

- Routine practice should not include Hand and wrist orthoses (splints) as they have no effect on function, pain or range of movement (Tyson et al 2011 [129])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Cardiorespiratory Training[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

- Rehabilitation should include individually tailored exercise interventions to improve cardiorespiratory fitness.Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Practice Statement

Consensus-based Recommendations

- Commence cardiorespiratory training during their inpatient stay.

- Encourage to participate in ongoing regular physical activity regardless of level of disability.Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Strength Training[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation

- Progressive resistance training should be offered to those with reduced strength in their arms or legs. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Circuit Class[edit | edit source]

Aquatherapy[edit | edit source]

Electrotherapy[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation

- Electrical stimulation may be used for those with reduced strength in their arms or legs (particularly for those with less than antigravity strength).

- Electrical stimulation may be used to prevent or reduce shoulder subluxation. (Vafadar et al 2015 [75])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation[edit | edit source]

TENS[edit | edit source]

Electromyographic Biofeedback[edit | edit source]

Spasticity Management[edit | edit source]

Stretch[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation AGAINST

- Routine use of stretch to reduce spasticity is not recommended.(Katalinic et al 2010 [64]; Kim et al 2013 [65]; Jung et al 2011 [66])

- Adjunct therapies to Botulinum toxinum A such as electrical stimulation, casting, taping and stretching may be used to reduce spasticity. (Stein et al 2015 [56]; Krewer et al 2014 [57]; Etoh et al 2015 [58]; Ochi et al 2013 [59]; Wu et al 2014 [60]; Yamaguchi et al 2012 [61]; Mills et al 2016 [62]; Santamato et al 2015 [63])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Botulinum Toxin[edit | edit source]

Weak Recommendation

- Botulinum Toxin A in addition to rehabilitation therapy may be used to reduce upper limb spasticity but is unlikely to improve activity or motor function. (Foley et al 2013 [38]; Dashtipour et al 2015 [39]; Baker et al 2015 [40]; Gracies et al 2014 [42])

- Botulinum Toxin A in addition to rehabilitation therapy may be useful for improving muscle tone in patients with lower limb spasticity but is unlikely to improve motor function or walking. (Wu et al 2016 [60]; McIntyre et al 2012 [51]; Olvey et al 2010 [52])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Contracture Management[edit | edit source]

Strong Recommendation AGAINST

- For people with stroke at risk of developing contracture, routine use of splints or prolonged positioning of upper or lower limb muscles in a lengthened position (stretch) is not recommended. (Katalinic et al 2010 [64])Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titlePractice Statement

Consensus-based Recommendations

- For stroke survivors, serial casting may be trialled to reduce severe, persistent contracture when conventional therapy has failed.

- For stroke survivors at risk of developing contracture or who have developed contracture, active motor training to elicit muscle activity should be provided.

Fatigue Management[edit | edit source]

Practice Statement

Consensus-based Recommendations

- Therapy for stroke survivors with fatigue should be organised for periods of the day when they are most alert.

- Information and education about fatigue should be provided to individuals with Stroke and their Families/Carers

- Potential modifying factors for fatigue should be considered including avoiding sedating drugs and alcohol, screening for sleep- related breathing disorders and depression

- While there is insufficient evidence to guide practice, possible interventions could include exercise and improving sleep hygiene

[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Veerbeek JM, van Wegen E, van Peppen R, van der Wees PJ, Hendriks E, Rietberg M, Kwakkel G. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014 Feb 4;9(2):e87987.

- ↑ Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management A Quick Guide for Physiotherapy. National Stroke Foundation, Australia, 2010.

- ↑ Veerbeek JM, van Wegen E, van Peppen R, van der Wees PJ, Hendriks E, Rietberg M, Kwakkel G. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014 Feb 4;9(2):e87987.

- ↑ Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of Patients With Stroke: Rehabilitation, Prevention and Management of Complications, and Discharge Planning: a National Clinical Guideline. (2010)

- ↑ Bang DH, Cho HS. Effect of body awareness training on balance and walking ability in chronic stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of physical therapy science. 2016;28(1):198-201.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 van Duijnhoven HJ, Heeren A, Peters MA, Veerbeek JM, Kwakkel G, Geurts AC, Weerdesteyn V. Effects of Exercise Therapy on Balance Capacity in Chronic Stroke. Stroke. 2016 Oct 1;47(10):2603-10.

- ↑ Stanton R, Ada L, Dean CM, Preston E. Biofeedback improves activities of the lower limb after stroke: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2011 Dec 31;57(3):145-55.

- ↑ English C, Hillier SL. Circuit class therapy for improving mobility after stroke. The Cochrane Library. 2010 Jan 1.

- ↑ Mehrholz J, Pohl M, Elsner B. Treadmill training and body weight support for walking after stroke. The Cochrane Library. 2014 Jan 1.

- ↑ Corbetta D, Imeri F, Gatti R. Rehabilitation that incorporates virtual reality is more effective than standard rehabilitation for improving walking speed, balance and mobility after stroke: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2015 Jul 31;61(3):117-24.

- ↑ Rodrigues-Baroni JM, Nascimento LR, Ada L, Teixeira-Salmela LF. Walking training associated with virtual reality-based training increases walking speed of individuals with chronic stroke: systematic review with meta-analysis. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2014 Dec;18(6):502-12.

- ↑ Mehrholz J, Elsner B, Werner C, Kugler J, Pohl M. Electromechanical-assisted training for walking after stroke. Stroke. 2013 Oct 1;44(10):e127-8.

- ↑ Stanton R, Ada L, Dean CM, Preston E. Biofeedback improves activities of the lower limb after stroke: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2011 Dec 31;57(3):145-55.

- ↑ Nascimento LR, de Oliveira CQ, Ada L, Michaelsen SM, Teixeira-Salmela LF. Walking training with cueing of cadence improves walking speed and stride length after stroke more than walking training alone: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2015 Jan 31;61(1):10-5.

- ↑ Howlett OA, Lannin NA, Ada L, McKinstry C. Functional electrical stimulation improves activity after stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2015 May 31;96(5):934-43.

- ↑ Barclay RE, Stevenson TJ, Poluha W, Ripat J, Nett C, Srikesavan CS. Interventions for improving community ambulation in individuals with stroke. The Cochrane Library. 2015 Jan 1.

- ↑ Tyson SF, Kent RM. The effect of upper limb orthotics after stroke: a systematic review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011 Jan 1;28(1):29-36.

- ↑ Momosaki R, Abo M, Watanabe S, Kakuda W, Yamada N, Kinoshita S. effects of ankle–foot orthoses on functional recovery after stroke: a propensity score analysis based on Japan rehabilitation database. PloS one. 2015 Apr 2;10(4):e0122688.

- ↑ Van Delden AE, Peper CE, Beek PJ, Kwakkel G. Unilateral versus bilateral upper limb exercise therapy after stroke: a systematic review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2012 Feb 5;44(2):106-17.

- ↑ Coupar F, Pollock A, Van Wijck F, Morris J, Langhorne P. Simultaneous bilateral training for improving arm function after stroke. The Cochrane Library. 2010 Apr 14.

- ↑ Morris DM, Taub E, Mark VW. Constraint-induced movement therapy: characterizing the intervention protocol. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42(3):257–68

- ↑ Taub, E.,Uswatte, G. Constraint-induced movement therapy: answers and questions after two decades of research. 2006 NeuroRehabilitation, 21(2), 93-95.

- ↑ Corbetta D, Sirtori V, Castellini G, Moja L, Gatti R. Constraint‐induced movement therapy for upper extremities in people with stroke. The Cochrane Library. 2015.

- ↑ Wee SK, Hughes AM, Warner M, Burridge JH. Trunk restraint to promote upper extremity recovery in stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2014 Sep;28(7):660-77.

- ↑ Howlett OA, Lannin NA, Ada L, McKinstry C. Functional electrical stimulation improves activity after stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2015 May 31;96(5):934-43.