Rhabdomyolysis

Original Editors - Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Emily Kordik, Michael Beavin, George Tate, Elaine Lonnemann, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Kim Jackson, Jason Copelin, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Candace Goh and Lauren Lopez

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Rhabdomyolysis is a serious condition caused by muscle injury. Rhabdomyolysis is serious and can be life-threatening[1].

- The etiology of rhabdomyolysis can be classified as: nontraumatic eg infections ; or traumatic, traumatic rhabdomyolysis are crush syndrome from accidents, earthquakes, and other natural and manufactured disasters[2].

- When muscle tissue gets seriously injured, it breaks down and dies, releasing its contents (including myoglobin) into the bloodstream. Myoglobin is toxic to the kidneys, and can lead to kidney complications, such as kidney failure, and changes in balance of electrolytes in the blood, which can lead to serious problems with the heart and other organs[1].

Image 1: Urine from a person with rhabdomyolysis showing the characteristic brown discoloration as a result of myoglobinuria

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Approximately 25,000 cases of rhabdomyolysis are reported each year in the USA.

- The prevalence of acute kidney injury in rhabdomyolysis is about 5 to 30%[2]

- Eighty-five percent of victims of traumatic injuries develop rhabdomyolysis.[3]

- It is also suggested that victims of severe injury that develop rhabdomyolysis and later acute renal failure have a mortality of 20%.[3]

- Rhabdomyolysis can occur at any age, but the majority of cases are seen in adults.

- Males, African-American race, obesity, age more than 60 are factors that demonstrate a higher incidence of rhabdomyolysis.

- The most common cause for rhabdomyolysis in children is infection(30%). [2]

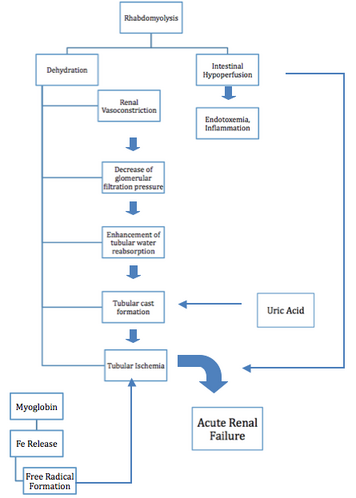

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Rhabdomyolysis occurs due to injury eg mechanical, chemical, toxins, poisons, burns. These injuries have a detrimental effect to the cell membranes throughout the body. When a cell membrane is damaged the breakdown releases organic and inorganic intracellular components eg potassium, myoglobin, lactic acid, purines, and phosphate which enter the circulation.[4]

After the restoration of blood flow after the injury these components become toxic to the body and in most cases are life threatening, making rhabdomyolysis a medical emergency.[5] Myoglobin levels rise within hours of muscle damage, but can return to normal in 1-6 hours if continuous muscle injury is not present.[6]

Myoglobin is usually filtered through glomeruli (of the kidneys) and reabsorbed in the proximal tubules by endocytosis, however when rhabdomyolysis occurs there is an excess of myoglobin, which overloads the proximal tubule cells ability to convert iron to ferritin, which then results in intracellular ferrihemate accumulation.[6] Since iron can donate and except electrons as well as having the ability to generate free radicals the urine’s pH can lead to metabolic acidosis. This process puts oxidative stress and injury to the renal cells, which if untreated can lead to renal cell failure.[5]

When there is an excess of myoglobin the tubules are unable to reabsorb it.[5][4] Systemic vasoconstriction sets in which results in water reabsorption in renal tubules, which then increases myoglobin concentration in urine. This in turn causes formation of casts that obstruct renal tubules. Another contributing factor of cast formation is apoptosis that occurs in epithelial cells.[6] This obstruction causes formation of free radicals from iron, which can lead to renal failure.[5]

Potassium is another byproduct of muscle lysis. With too much potassium in the circulation hyperkalemia can occur, which is life threatening, due to its cardiotoxicty effects.[5] Cardiac arrhythmias can occur due to increased levels of potassium in the blood. In some cases, early death occurs due to ventricular fibrillation.[7]

Calcium accumulation in the muscles occurs in the early stages of rhabdomyolysis. Massive calcification of necrotic muscles can occur which can lead to hypercalcemia.[6] If hyperkalemia is present hypercalcemia can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, muscular contraction, or seizures.[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology for rhabdomyolysis can be classified into two broad categories. Traumatic or physical causes and nontraumatic or nonphysical causes.

The most common causes of rhabdomyolysis are trauma, immobilization, sepsis, and cardiovascular surgeries[2]. Causes of rhabdomyolysis include:

- trauma or crush injuries, eg car accident

- taking illegal drugs eg cocaine, amphetamines or heroin

- extreme muscle exertion, eg running marathons or improper resistance training

- a side effect of some medicines, eg cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins) or amphetamines used for ADHD, although the risk is very low

- prolonged muscle pressure eg when someone is lying unconscious on a hard surface

- hyperthermia or heat stroke

- dehydration

- high fever

- an infection

- being bitten or stung by wasps, hornets or snakes

- having a seizure

- drinking too much alcohol

- being born with some genetic conditions or muscular dystrophies

You are at greater risk of rhabdomyolysis if you are an older adult, have diabetes, take part in extreme sports or use a lot of drugs or alcohol.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of rhabdomyolyis vary from person to person. The three most common signs and symptoms are muscle pain, weakness, and dark urine.[3][5]

Muscle pain as well as weakness and tenderness may be general or specific to muscle groups. The calves and low back are the most general muscle groups that are affected.[3] According to the author Efstratiadis, back pain and limb pain are the most frequent sites in patients with rhabdomyolysis.[5] However, over 50% of the patients with rhabdomyolysis may not complain of muscle pain or weakness.[3]

- The initial sign of rhabdomyolysis is discolored urine which can range from pink to dark black.[3][5]

- Other signs and symptoms include, local edema, cramps, hypotension, malaise, fever, tachycardia, nausea and vomiting.[3][5]

- Often during the early stages of rhabdomyolysis the following conditions may also be present: hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, elevated liver enzymes, cardiac dysrrhythmias and cardiac arrest.[3]

- Some late complications include acute renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[3]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Blood tests for creatine kinase, a product of muscle breakdown, and urine tests for myoglobin can help diagnose rhabdomyolysis (although in half of people with the condition, the myoglobin test may come up negative). Other tests may rule out other problems, confirm the cause of rhabdomyolysis, or check for complications.

- Common complications of rhabdomyolysis include very high levels of potassium in the blood, which can lead to an irregular heartbeat or cardiac arrest and kidney damage (which occurs in up to half of patients).

- About one in four also develop problems with their liver.

- Compartment syndrome may also occur after fluid resuscitation. This serious compression of nerves, blood vessels, and muscles can cause tissue damage and problems with blood flow[8].

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Early diagnosis and treatment of rhabdomyolysis and its causes are keys to a successful outcome. You can expect full recovery with prompt treatment. Doctors can even reverse kidney damage. However, if compartment syndrome is not treated early enough, it may cause lasting damage.

Clients with rhabdomyolysis, you will be admitted to the hospital. Treatment with intravenous (IV) fluids helps maintain urine production and prevent kidney failure. Rarely, dialysis treatment may be needed to help kidneys filter waste products while they are recovering. Management of electrolyte abnormalities (potassium, calcium and phosphorus) helps protect the heart and other organs. Client may also need a surgical procedure (fasciotomy) to relieve tension or pressure and loss of circulation if compartment syndrome threatens muscle death or nerve damage. In some cases, client may need to be in the intensive care unit (ICU) to allow close monitoring.

- Most causes of rhabdomyolysis are reversible.

- If rhabdomyolysis is related to a medical condition, such as diabetes or a thyroid disorder, appropriate treatment for the medical condition will be needed. And if rhabdomyolysis is related to a medication or drug, its use will need to be stopped or replaced with an alternative.[8]

- Hyperkalemia may be fatal and should be corrected vigorously

- Hypocalcemia should be corrected only if it causes symptoms

- Compartment syndrome requires immediate orthopaedic consultation for fasciotomy[9]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

It is important to keep in mind the cause of rhabdomyolysis. It is important to not overexert the patient to prevent them from creating more muscle breakdown. The most important thing is for the patient to retain range of motion as well as to properly hydrate.

The physical therapist treating a patient with rhabdomyolysis must make sure that the patient is not having any urinary problems which includes urine color.[10] Some interventions would include range of motion exercises (both active and passive), aerobic training, and gradual resistance training.[10]

In a recent study on rehabilitation for Rhabdomyolysis associated with breast cancer treatment, it was reported that physical activity such as strengthening and aerobic exercises were safe and beneficial to minimise immobility [11]. Exercise is crucial for reducing cancer-related fatigue, enhancing quality of life, and preventing unnecessarily long treatment wait times. It is preferable to take a holistic approach when treating a patient who is under intense physical and mental strain using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). The settings for effective physical rehabilitation in aiding a person's improvement of independence, safety, and confidence were supplied by the coordination of transitions from acute care to in-patient rehabilitation in conjunction with holistic approach.

Exertional Rhabdomyolysis and Return to Sport[edit | edit source]

A client’s fitness level is extremely important when considering the development of a workout program. Exertional rhabdomyolysis may occur when a client is not accustomed to the mode or intensity of the exercise prescribed. Fitness professionals must understand the importance of initial fitness level and progressional overload so that the exercise stress challenges the client appropriately. Fitness specialists should also consider the risks when providing eccentric training in a hot environment or if the client has any genetic risk factors for rhabdomyolysis.

Physical Therapy Management Return to Sport[edit | edit source]

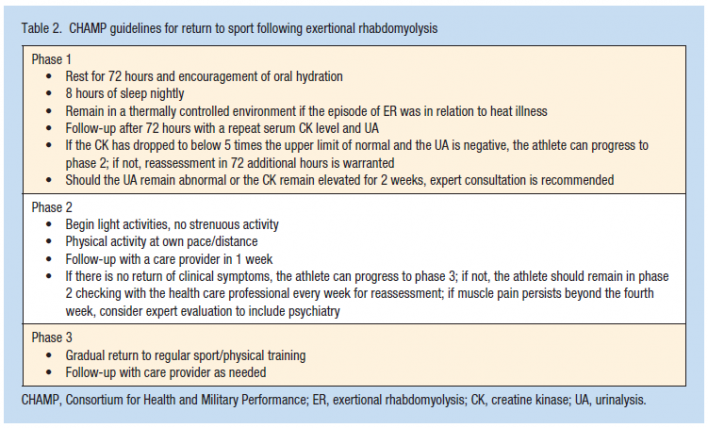

There is currently no evidence based guidelines for return to play after an episode of exertional rhabdomyolysis. However, a conservative return to sport protocol has been described by Consortium for Health and Military Performance (CHAMP) and is listed below.[12]

[12]

[12]

Image Courtesy of David C. Tietze, M.D.

Schleich et al, outlined a phased reintegration program for safe and effective return to play post exertional rhabdomyolysis (table 1 below). Following phase IV, athletes in the study continued with agility work, speed development, and resistance training under the supervision of strength and conditioning staff. Each athletes return-to-play time will vary depending on severity of rhabdomyolysis, previous fitness level, training experience and maturation.

Table 1. Overview of Phased Return [13]

Phase 1: Activities

Return to activities of daily living for 2 wk

Regular monitoring by athletic training staff

Screening for symptoms consistent with exertional rhabdomyolysis, sleep patterns, hydration, urine color, and class attendance

Monitoring of creatinine kinase and serum creatinine by primary care physician

Phase 2: Activities

Daily monitoring of hydration status, muscle soreness, and swelling

Initiation of physical activity: foam rolling, dynamic warm-up, aquatic jogging, and stretching

Phase 3: Activities

Daily monitoring of hydration status, muscle soreness, and swelling

Progression of physical activity: body-weight resistance movements, resistance training with elastic band, core training, stationary bicycling, and stretching

Phase 4: Activities

Daily monitoring of hydration status, muscle soreness, and swelling

Initiation of resistance training at 20%–25% of estimated 1-repetition maximum, agility exercises, and running

Risk stratification for recurrent rhabdomyolysis [14]

According to O’Connor et al., an athlete who experiences clinically relevant exertional rhabdomyolysis (ER) should first be risk-stratified as either low or high risk for a recurrence.

To be considered "suspicious for high risk,' at least one of the following conditions must exist or be present:

a. Delayed recovery (more than 1 wk) when activities have been restricted

b. Persistent elevation of CK (greater than five times the upper limit of the normal lab range) despite rest for at least 2 wk

c. ER complicated by acute renal injury of any degree

d. Personal or family history of ER

e. Personal or family history of recurrent muscle cramps or severe muscle pain that interferes with activities of daily living or sports performance

f. Personal or family history of malignant hyperthermia, or family history of unexplained complications or death following general anesthesia

g. Personal or family history of sickle cell disease or trait

h. Muscle injury after low to moderate work or activity

i. Personal history of significant heat injury (heat stroke)

j. Serum CK peak ≥ 100,000 U·L−1.

To be considered a "low risk" athlete, none of the high-risk conditions should exist, and at least one of the following conditions must exist or be present:

a. Rapid clinical recovery and CK normalization after exercise restrictions

b. Sufficiently fit or well trained athlete with a history of very intense training/exercise bout

c. No personal or family history of rhabdomyolysis or previous reporting of debilitating exercise-induced muscle pain, cramps, or heat injury

d. Existence of other group or team-related cases of ER during the same exercise sessions

e. Suspected or documented concomitant viral illness or infectious disease

f. Taking a drug or dietary supplement that could contribute to the development of ER

Complete history and physical examination should be completed and referral to experts for consideration of myopathic disorders before return to sport for any individual at high risk.

Prevention of recurrent episodes in pre-disposed individuals [15]

Regardless of cause:

• Avoid triggers

• Hydrate

• Warm-up before exercise

Fatty acid beta-oxidation:

• Low fat diet

• Replacement of essential fatty acids with walnut or soy oils

Vitamin D deficiency:

• Monitoring and normalization of vitamin D levels

Brief video regarding physical therapy management[16][17]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NDdoiNNaMKI

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Most Common Differential Diagnoses[18]

- Burns, Electrical

- Carnitine Deficiency

- Child Abuse and Neglect, physical abuse

- Dermatomyositis

- Multisystem Organ Failure of Sepsis

- Myoglobinuria[4]

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

- Sepsis

- Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

- Systemic Lupus Erythmatosus

- Thromboembolism

- Toxic Shock Syndrome

- Toxicity, Ethanol

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Health Direct Rhabdomyolysis Available: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/rhabdomyolysis (accessed 17.9.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Stanley M, Adigun R. Rhabdomyolysis. 2017 Available: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/28509/(accessed 17.9.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Huerta-Alardin AL, Varon J, Marik P. Bench-to-beside review: Rhabdomyolysis - an overview for clinicians. Critical Care 2005; 9: 158-169

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Vanholder R, Mehmet S, Erek E, Lameire N. Rhabdomyolysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2000; 1553-1561.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Efstratiadis G, Voulgaridou A, Nikiforou D, et al. Rhabdomyolysis updated. Hippokratia 2007; 11(3): 129-137.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Bagley WH, Yang H, Shah KH. Rhabdomyolysis. Intern Emergency Medicine 2007; 2: 210-218

- ↑ Savage DCL, Forbes M. Idiopathic Rhabdomyolysis. Archieves of Disease in Childhood 1971; 26: 594-607

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 WebMd Rhabdomyolysis Available: https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/rhabdomyolysis-symptoms-causes-treatments (accessed 17.9.2021)

- ↑ Khan F. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. The Netherlands Journal Of Medicine [serial online]. October 2009;67(9):272-283. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 23, 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Brown T. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis: Early Recognition is Key. The Physician and Sports Medicine 2004; 32: 1-5

- ↑ Burns G, Wilson CM. Rehabilitation for Rhabdomyolysis Associated With Breast Cancer Treatment. Cureus. 2020 Jun 15;12(6).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tietze DC, Borchers J. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis in the Athlete: A Clinical Review. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2014;:1941738114523544.

- ↑ Schleich, K., Slayman, T., West, D. and Smoot, K. (2016). Return to Play After Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Journal of Athletic Training, 51(5), pp.406-409.

- ↑ O'Connor, F., Brennan, F., Campbell, W., Heled, Y. and Deuster, P. (2008). Return to Physical Activity After Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 7(6), pp.328-331.

- ↑ Hannah-Shmouni F, McLeod K, Sirrs S. Recurrent exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(4):426-430. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110518.

- ↑ Schleich, K., Slayman, T., West, D. and Smoot, K. (2016). Return to Play After Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Journal of Athletic Training, 51(5), pp.406-409.

- ↑ O'Connor, F., Brennan, F., Campbell, W., Heled, Y. and Deuster, P. (2008). Return to Physical Activity After Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 7(6), pp.328-331.

- ↑ Muscal E. Rhabdomyolysis: Differential Diagnoses and Workup. eMedicine 2009.