Piriformis Syndrome

Original Editors - Marlies Verbruggen

Top Contributors - Marlies Verbruggen, Vidya Acharya, Admin, Kim Jackson, Kudzanayi Ronald Muzenda, Ajay Upadhyay, Rachael Lowe, Nupur Smit Shah, Maëlle Cormond, Carolie Siffain, WikiSysop, Wendy Snyders, Daphne Jackson, Claire Knott, Heba El Saeid, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Wanda van Niekerk, Ahmed M Diab and Kai A. Sigel

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Piriformis syndrome (PS) is a painful musculoskeletal condition, characterized by a combination of symptoms including buttock or hip pain.[1][2][3] In several articles, piriformis syndrome is defined as a peripheral neuritis of the branches of the sciatic nerve caused by an abnormal condition of the piriformis muscle (PM), such as an injured or irritated muscle.[4][3] There are more women diagnosed with Piriformis syndrome than men, with a female–to–male ratio of 6:1. This ratio can be explained by the wider quadriceps femoris muscle angle in the os coxae of women.[5][6][3] There are two types of piriformis syndrome. The first type is called “Primary piriformis syndrome.” It is caused by an anatomical variation, like a split piriformis muscle, a split sciatic nerve or an anomalous sciatic nerve path. The second type is called “Secondary piriformis syndrome.” It is the result of a precipitating cause, such as a macrotrauma, microtraumata, ischemic mass effect or local ischemia.[6][3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The piriformis muscle (PM) originates from the pelvic surface of the sacral segments S2-S4 in the regions between and lateral to the anterior sacral foramina, the sacro-iliac joint (superior margin of the greater sciatic notch), the anterior sacroiliac ligament and occasionally the anterior surface of the sacro-tuberous ligament. It passes through the greater sciatic notch to insert onto the greater trochanter of the femur.

The PM is functionally involved with external rotation, abduction and partial extension of the hip.[7][8]

The sciatic nerve generally exits the pelvis below the belly of the muscle, however many congenital variations may exist.[8]

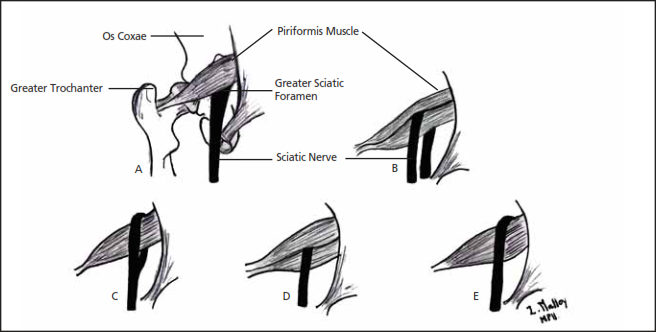

The relationships between the PM and sciatic nerve have been classified by Beaton and Anson using a six category classification system (Beaton and Anson, 1938). An anomalous relationship would be labelled between type ‘‘B’’ through type ‘‘F’’ since type ‘‘A’’ is considered to have a normal relationship between the PM and the sciatic nerve.[9]

Variations in the relationship of the sciatic nerve to the piriformis muscle shown on the diagram above: (A) the sciatic nerve exiting the greater sciatic foramen along the inferior surface of the piriformis muscle; the sciatic nerve splitting as it passes through the piriformis muscle with the tibial branch passing (B) inferiorly or (C) superiorly; (D) the entire sciatic nerve passing through the muscle belly; (E) the sciatic nerve exiting the greater sciatic foramen along the superior surface of the piriformis muscle. The nerve may also divide proximally, where the nerve or a division of the nerve may pass through the belly of the muscle, through its tendons or between the part of a congenitally bifid muscle.[3]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

According to Boyajian- O’ Neill L.A. et al., who has a level of evidence of 2A, there are two types of piriformis syndrome- primary and secondary.

Primary piriformis syndrome

Primary piriformis syndrome has an anatomical cause, with variations such as a split piriformis muscle, split sciatic nerve, or an anomalous sciatic nerve path. Among patients with piriformis syndrome, fewer than 15% of cases have primary causes.[3] At present, there are no accepted values for the prevalence of the anomaly and little evidence to support whether or not the anomaly of the sciatic nerve causes piriformis syndrome or other types of sciatica.[9] These findings suggest that piriformis and sciatic anomalies may not be as important to the pathophysiology of piriformis syndrome as previously thought.[9]

Secondary piriformis syndrome

Secondary piriformis syndrome occurs as a result of a precipitating cause, including macrotrauma, microtrauma, ischemic mass effect, and local ischemia.

Piriformis syndrome is most often (50% of the cases) caused by macrotrauma to the buttocks, leading to inflammation of soft tissue, muscle spasms, or both, with resulting nerve compression.

Muscle spasms of the PM are most often caused by direct trauma, post-surgical injury, lumbar and sacroiliac joint pathologies or overuse.[4][5][6][10][2][3]

PS may also be caused by shortening of the muscles due to altered biomechanics of the lower limb, low back and pelvic regions [7]. This can result in compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve. [4][6][10]

When there is a dysfunction of the piriformis muscle, it can cause various signs and symptoms such as pain in the sciatic nerve distribution, including the gluteal area, posterior thigh, posterior leg and lateral aspect of the foot.[5]Microtrauma may result from overuse of the piriformis muscle, such as in long-distance walking or running or by direct compression. An example of this kind of direct compression is known as “wallet neuritis”, which is a repetitive trauma caused by sitting on hard surfaces.[3]

Etiology of the piriformis syndrome[11]

| Gluteal trauma in the sacroiliac or gluteal areas | predisposing anatomic variants |

| Myofascial trigger points | Hypertrophy and spasm of the piriformis muscle |

| Secondary to laminectomy | Abcess, hematoma, myositis |

| Bursitis of the piriformis muscle | Neoplasms in the area of the infrapiriform foramen |

| Colorectal carcinoma | Neurinoma of the sciatic nerve |

| Episacroiliac lipoma | Intragluteal injection |

| Femoral nailing | Myositis ossificans of the piriformis muscle |

| Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome |

Other causative factors are anatomic variations of the divisions of the sciatic nerve, anatomic variations or hypertrophy of piriformis muscle, repetitive trauma, sacro-iliac arthritis and total hip replacement.[5][6][12][2] A Morton's Toe can also predispose the patient to developing piriformis syndrome. A fraction of the population is at high risk, particularly skiers, truck drivers, tennis players and long-distance bikers.[5]

Tonley JC[4] had another view about the cause of PS. He said: ”The piriformis muscle may be functioning in an elongated position or subjected to high eccentric loads during functional activities secondary to weak agonist muscles. For example, if the hip excessively adducts and internally rotates during weight-bearing tasks, due to weakness of the gluteal maximus and / or the gluteus medius, a greater eccentric load may be shifted to the piriformis muscle. Perpetual loading of the piriformis muscle through overlengthening and eccentric demand may result in sciatic nerve compression or irritation”.[4]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with piriformis syndrome have many symptoms that typically consist of persistent and radiating low back pain, (chronic) buttock pain, numbness, paraesthesia, difficulty with walking and other functional activities such as pain with sitting, squatting, standing, with bowel movements and dyspareunia in women.[4][5][1][12][3][13][14].

They can also have pressure pain on the buttock on the same side as the piriformis lesion and point tenderness over the sciatic notch in almost all instances.[13]]

Swelling in the legs and disturbances of sexual functions have also been observed in patients with PS.[13]

The buttock pain can radiate into the hip, the posterior aspect of the thigh and the proximal portion of the lower leg.[4]

There may be an aggravation of pain with activity, prolonged sitting or walking, squatting, hip adduction and internal rotation and maneuvers that increase the tension of the piriformis muscle.[4][5][1][12]

Depending on the patient, the pain can lessens when lying down, bending the knee or when walking. However, some patients cannot tolerate the pain in any position and can only find relief when they’re walking.[14][13]

Piriformis syndrome is not characterized by neurological deficits typical for a radicular syndrome, such as declined deep tendon reflexes and myotomal weakness. The patient may present with a limp when walking or with their leg in a shortened and externally rotated position while supine[1][13]. This external rotation while supine can be a positive piriformis sign, also called a splayfoot. It can be the result of a contracted piriformis muscle.[6][3]

Three specific conditions may contribute to PS:

- Myofascial referred pain from trigger points in the PM

- Adjacent muscles, nerve and vascular entrapment by the PM at the greater sciatic foramen

- Dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Dysfunction, lesion and inflammation of sacroiliac joint [1]

- Pseudoaneurysm in the inferior gluteal artery following gynaecologic surgery

- Thrombosis of the iliac vein [2]

- Painful vascular compression syndrome of the sciatic nerve, caused by gluteal varicosities

- Herniated intervertebral disc [3]

- Post-laminectomy syndrome or coccygodinia [4]

- Posterior facet syndrome at L4-5 or L5-S1 [5]

- Unrecognized pelvic fractures [6]

- Lumbar osteochondrosis

- Undiagnosed renal stones [15]

- Lumbosacral radiculopathies

- Osteoarthritis (lumbosacral spine)

- Sacroiliac joint syndrome

- Degenerative disc disease

- Compression fractures

- Intra-articular pathology in the hip joint: labral tears [9], femuro-acetabular impingement (FAI)[14]

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Tumors, cysts

- Gynaecological conditions

- Diseases such as appendicitis, pyelitis, hypernephroma, uterine disorders, prostate disorders and malignancies in pelvic viscera.

- Psychgenic disorders: physical fatigue, depression, frustration

- Sacroiliitis [13][16][11][4]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

There are two types of piriformis syndrome - primary and secondary.

- Primary piriformis syndrome has an anatomic cause, such as a split piriformis muscle, split sciatic nerve, or an anomalous sciatic nerve path.

- Secondary piriformis syndrome occurs as a result of a precipitating cause, including macrotrauma, microtrauma, ischemic mass effect, and local ischemia.

Among patients with piriformis syndrome, fewer than 15% of cases have primary causes. Piriformis syndrome is most often caused by macrotrauma to the buttocks, leading to inflammation of soft tissue, muscle spasm, or both, with resulting nerve compression. Microtrauma may result from overuse of the piriformis muscle, such as in long-distance walking or running or by direct compression. An example of this kind of direct compression is “wallet neuritis” (ie, repetitive trauma from sitting on hard surfaces).

Investigations[edit | edit source]

Radiographic studies have limited application to the diagnosis of piriformis syndrome. Although standard antero-posterior radiographs of the pelvis and hips, lateral views of the hips and either CT or MRI of the lumbar spine are recommended to rule out the possibility that the symptoms experienced by the patients originate from the spine or the hip joint.[11]

Electromyography (EMG) may be also beneficial in differentiating piriformis syndrome from other possible disorders, such as intervertebral disc herniation. Interspinal nerve impingement will cause EMG abnormalities of muscles proximal to the piriformis muscle. In patients with piriformis syndrome however, EMG results will be normal for muscles proximal to the piriformis muscle and abnormal for muscles distal to it.

Electromyography examinations that incorporate active maneuvers, such as the FAIR test, may have a greater specificity and sensitivity than other available tests for the diagnosis of piriformis syndrome[3]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

Examination[edit | edit source]

A complete neurological history and physical assessment of the patient is essential for an accurate diagnosis. The physical assessment should include the following points:

- an osteopathic structural examination with special attention to the lumbar spine, pelvis and sacrum, as well as any leg length discrepancies

- diagnostic tests

- deep-tendon reflex testing, strength and sensory testing

Diagnostic tests [edit | edit source]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

The patient reports sensitivity during palpation at the greater sciatic notch, in the region of sacroiliac joint or over the piriformis muscle belly. It is possible to detect the spasm of the PM by careful, deep palpation.[6][1][12]

With deep digital palpation in the gluteal and retro-trochanteric area, there may be tenderness and pain with an exacerbation of tightness and leg numbness.[16]

Pace sign[edit | edit source]

Pace’s sign consists of pain and weakness by resisted abduction and external rotation of the hip in a sitting position. A positive test is occurs in 46.5% of the patients with piriformis syndrome.[5][1][3][11]

Lasèque sign / Straight Leg Raise Test[11][edit | edit source]

The patient reports buttock and leg pain during passive a straight leg raise performed by the examiner.[16]

Freiberg sign[edit | edit source]

Involves pain and weakness on passive forced internal rotation of the hip in the supine position. The pain is thought to be a result of passive stretching of the piriformis muscle and pressure placed on the sciatic nerve at the sacrospinous ligament. Positive in 56,2% of the patients.[11]

FAIR[16][edit | edit source]

Painful flexion-adduction-internal rotation

Beatty’s maneuver[edit | edit source]

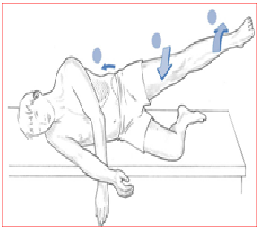

An active test that involves elevation of the flexed leg on the painful side, while the patient is lying on the asymptomatic side. The abduction causes deep buttock pain in patients with PS, but back and leg pain in patients with lumbar disc disease.[11]

The Hughes test[edit | edit source]

External isometric rotation of the affected lower extremity following maximal internal rotation may also be positive in PS patients.[11]

Hip Adbuction Test[edit | edit source]

The patient lies on the side with lower leg flexed to provide support and the upper leg straight, in line with the trunk. The practitioner stands in front of the patient at the level of the feet and observes (no hands on) as the patient is asked to abduct the leg slowly.

Normal – Hip abduction to 45°.

Abnormal – if hip flexion occurs (indicating TFL shortness) and/or leg externally rotates (indicating piriformis shortening) and/or ‘hiking’ of the hip occurs at the outset of the movement (indicating quadratus overactivity and therefore, by implication, shortness)

Patients with piriformis syndrome may also present with gluteal atrophy, as well as shortening of the limb on the affected side.

In chronic cases muscle hypotrophy is present in the affected extremity.

Trendelenburg test may also be positive.[16]

Management/Intervention[edit | edit source]

Medical management[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment for piriformis syndrome includes pharmacological agents (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants and neuropathic pain medication), physical therapy, lifestyle modifications and psychotherapy.[11]

Injections of local anaesthetics, steroids, and botulinum toxin into the PM muscle can serve both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The practitioner should be familiar with variations in the anatomy and the limitations of landmark-based techniques. An ultrasound guided injection technique has recently been utilized. This technique has been shown to have both diagnostic and therapeutic value in the treatment of PS.[11]

Piriformis syndrome often becomes chronic and pharmacological treatment is recommended for a short time period.[16]

Surgical management[edit | edit source]

Surgical interventions should be considered only when nonsurgical treatment has failed and the symptoms are becoming intractable and disabling. Classic indications for surgical treatment include abscess, neoplasms, hematoma, and painful vascular compression of the sciatic nerve caused by gluteal varicosities.[11]

Surgical release with tenotomy of the piriformis tendon to relieve the nerve from the pressure of the tense muscle has resulted in immediate pain relief, as reported by several authors.

Sometimes, the obturator internus muscle should be considered as a possible cause of sciatic pain. However, the diagnosis of the obturator internus syndrome can only be made by ruling out other possible causes of sciatic pain, which is similar to the manner in which piriformis syndrome is diagnosed.[16] Surgical release of the internal obturator muscle can result in both a short- and long-term reduction in pain in patients with retro-trochanteric pain syndrome and should be considered if conservative treatment fails.

The postoperative management consists of partial weight-bearing using crutches for 2 weeks and unrestricted range of motion exercises. The above surgical approach has shown promising short-term results[16]

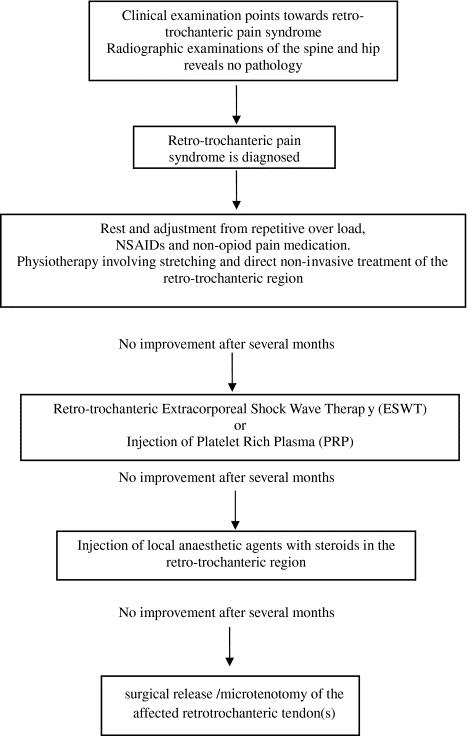

The treatment algorithm for retro-trochanteric pain syndrome:

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Although there is a paucity of recently published controlled trials in which critically examine the effectiveness of the noninvasive management modalities[11], a number of methods exists for the treatment of ‘Piriformis Syndrome’.

The non-invasive treatments include: physical therapy, (osteopathic) manipulative treatment[3] and lifestyle modification[11].

According to Tonley et al., the most commonly reported physical therapy interventions include ultrasound, soft tissue mobilization, piriformis stretching, hot packs or cold spray and various lumbar spine treatments (evidence level 2A). In addition, its case report Tonley et al. describes an alternative treatment approach for piriformis syndrome. The intervention focused on functional exercises Therapy Exercises for the Hip aimed at strengthening the hip extensors, abductors and external rotators, as well as correction of faulty movement patterns (evidence level 4). Despite positive outcomes (level of evidence 4) full resolution of low back pain, cessation of buttock and thigh pain) in this single case report care must be taken in establishing cause and effect based on a single patient. Further investigation is needed[4]

To achieve a 60 – 70% improvement, the patient usually follows 2 – 3 treatments weekly for 2-3 months.[15][18] (level of evidence 2b)

First of all, the patient must be placed in contralateral decubitus and FAIR position (Flexed Adducted Internally Rotated). Start with an ultrasound treatment: 2.0-2.5 W/cm2, for 10-14 minutes. Apply the ultrasound gel in broad strokes longitudinally along the piriformis muscle from the conjoint tendon to the lateral edge of the greater sciatic foramen.[4][5][15][2][18][3] (level of evidence 2b) Before stretching the piriformis muscle, treat the same location with hot packs or cold spray for 10 minutes. The use of hot and cold before stretching is very useful to decrease pain. [4][5][15][18][3] After that, begin with stretching of the piriformis which can be executed in a variety of ways. Stretch the piriformis muscle by applying manual pressure to the muscle’s inferior border. It is important not to press downward, rather directing pressure tangentially, toward the ipsilateral shoulder. When pressing downward, the sciatic nerve will compress against the tendinous edge of the gemellus superior. However, when applying tangential pressure, the muscle’s grip will weaken on the nerve and relieve the pain of the syndrome.[4][15][18][3]

Another way to stretch this muscle is in the FAIR position. The patient lies in a supine position with the hip flexed, adducted and internally rotated. Then the patient brings his foot of the involved side across and over the knee of the uninvolved leg. We can enhance the stretch, by letting the physical therapist perform a muscle–energy technique. This technique involves the patient abducting his limb against light resistance, which is provided by the therapist for 5-7 seconds, with 5-7 repetitions.[5][6][15][18]

After stretching, continue with myofascial release at the lumbosacral paraspinal muscles and McKenzie exercises. When the patient lies in the FAIR position, the lumbosacral corset can be used.[15][18][3]

The therapist can also give several tips to avoid an aggravation of the symptoms. This includes:

- Avoid sitting for a long period

- Stand and walk every 20 minutes

- Make frequent stops when driving to stand and stretch

- Prevent trauma to the gluteal region

- Avoid further offending activities.

- Daily stretching is recommended to avoid the recurrence of the piriformis syndrome.[5][6][3]

The patient can also perform several exercises and treatments at home including:

- Rolling side to side with flexion and extension of the knees while lying on each side

- Rotate side to side while standing with the arms relaxed for 1 minute every few hours

- Take a warm bath

- Lie flat on the back and raise the hips with your hands and pedal with the legs like you are riding a bicycle

- Knee bends, with as many as 6 repetitions every few hours.[5]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Boyajian- O’ Neill L.A. et al. Diagnosis and Management of Piriformis syndrome : an osteopathic approach. The journal of the American and osteopathic association Nov 2008; 108(11): 657-664. (2A)

Jankovic D, Peng P, van Zundert A. Brief review: piriformis syndrome: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Can J Anaesth. 2013 Oct;60(10):1003-12. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0009-5. Epub 2013 Jul 27. PubMed PMID: 23893704 (2A)

Resources[edit | edit source]

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliac_joint_syndrome

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Deep_Vein_Thrombosis

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Disc_Herniation

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Coccygodynia

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Facet_Syndrome

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Pelvic_Fractures

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Spinal_Stenosis

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Nephrolithiasis_%28Kidney_Stones%29

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Radiculopathy

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Degenerative_Disc_Disease

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_compression_fracture

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Labral_Tear

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Femoroacetabular_Impingement

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliitis

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Las%C3%A8gue_sign

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/FAIR_test

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Trendelenburg_Test

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Roland%E2%80%90Morris_Disability_Questionnaire

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Piriformis syndrome (PS) is a painful musculoskeletal condition and is most often caused by macrotrauma to the buttocks, leading to inflammation of soft tissue, muscle spasms, or both, with resulting nerve compression.

Patients with piriformis syndrome have many symptoms that typically consist of persistent and radiating low back pain, (chronic) buttock pain, numbness, paraesthesia, difficulty with walking and other functional activities.

A complete neurological history and physical assessment of the patient is essential for an accurate diagnosis. The physical assessment should include the following points:

- osteopathic structural examination with special attention to the lumbar spine, pelvis and sacrum, as well as any leg length discrepancies

- diagnostic tests

- deep-tendon reflex testing, strength and sensory testing

When diagnosed, patients need to first rest and then adjustments are needed in regards to repetitive overloads placed on the body. NSAIDs and non-opiod pain medications are recommended for a short period but patients need to perform physiotherapy including stretching and direct non-invasive treatment of the retro-trochanteric region. Surgical intervention should be considered only when nonsurgical treatment has failed and the symptoms are becoming intractable and disabling.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Kirschner JS, Foye PM, Cole JL. Piriformis syndrome, diagnosis and treatment. Muscle Nerve Jul 2009;40(1):10-18

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cramp F, Bottrell O, et al. Non–surgical management of piriformis syndrome: A systematic review. Phys Ther Rev 2007;12:66-72. ( A1)

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Lori A, Boyajian-O’ Neill, et al. Diagnosis and management of piriformis syndrome:an osteopathic approach. J Am Osteopath Assoc Nov 2008;108(11):657-664.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Tonley JC, Yun SM, et al. Treatment of an individual with piriformis syndrome focusing on hip muscle strengthening and movement reeducation: a case report. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40(2):103-111.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 Shah S, Wang TW. Piriformis syndrome. eMedicine specialities: Sports medicine: hip 2009 fckLR http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/87545-overview

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Klein MJ. Piriformis syndrome. eMedicine Specialities: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Lower limb Musculoskeletal conditions 2010 fckLR http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/308798-overview

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Cynthia Chapman DC a, Barclay W. Bakkum DC, PhD b, Chiropractic management of a US Army veteran with low back pain and piriformis syndrome complicated by an anatomical anomaly of the piriformis muscle: a case study , Journal of Chiropractic Medicine (2012) 11, 24–29 (3B)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kevork Hopayian, Fujian Song, Ricardo Riera, Sidha SambandanThe clinical features of the piriformis syndrome: a systematic review (2A)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 NICOLAS ROYDON SMOLL, Variations of the Piriformis and Sciatic Nerve With Clinical Consequence: A Review, Clinical Anatomy 23:8–17 (2010) (3A)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hopayian K, Song F, Riera R, Sambandan S. The clinical features of the piriformis syndrome: a systematic review. European Spine Journal. 2010 Dec 1;19(12):2095-109.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 Jankovic D, Peng P, van Zundert A. Brief review: piriformis syndrome: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Can J Anaesth. 2013 Oct;60(10):1003-12. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0009-5. Epub 2013 Jul 27. PubMed PMID: 23893704.(2A)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Hopayian K. The clinical features of the piriformis syndrome. Surgical and radiologic anatomy. 2012 Sep 1:1-.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Kunbong Choi, The etiology, diagnosis and treatment of piriformis syndrome (2004)(5)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Conservative Management of Piriformis Syndrome Douglas Volume 27 * Number 2 * 1992 * Journal of Athletic Training (2C)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Fishman LM, Dombi GW, et al. Piriformis syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome a 10-Year study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil March 2002;83:295-301

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 Meknas K, Johansen O, Kartus J. Retro-trochanteric sciatica-like pain: current concept. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011 Nov;19(11):1971-85. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1573-2. Epub 2011 Jun 16. Review. PubMed PMID: 21678093; (2A)

- ↑ Physiotutors. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdAD9GNv8FI

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Fishman LM, Anderson C, Rosner B. Botox and physical therapy in the treatment of the piriformis syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002;81(12):936-942. (A2)