Metatarsalgia

Original Editors - David De Meyer

Top Contributors - Diego Zaragoza, Lucinda hampton, Maxim de Clippele, Kim Jackson, David De Meyer, Evan Thomas, Admin, Adam Vallely Farrell, Rachael Lowe, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Jess Bell, 127.0.0.1, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Khloud Shreif and WikiSysop

Definition[edit | edit source]

Metatarsalgia is a general term used to denote a painful foot condition in the metatarsal region (the area just proximal the toes, more commonly referred as the ball-of-the-foot). This is a disorder that can affect the bones as well as joints at the plantar forefoot.

Metatarsalgies are often accompanied by excessive callus formation over a bony protrusion, with severe pain and pressure sensitivity around the callus.[1,2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The most important and relevant anatomy is the metatarsals. The metatarsals are proximally connected to the tarsal bones and distally to the the phalanges. The joints between the metatarsals and the repsective proximal phalanx is called the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP). These joints form the ball of the foot, and the ability yo move in these joints is very important for normal walking. Knowledge of the other foot bones and structures (muscles, tendons, ligaments…) is also necessary to distinguish the sctructures and pathologies.[1]

More information about anatomy of the foot and ankle can be found here.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

There can be multiple causative factors that lead to the development of metatarsalgia, but the majority seem to be related to foot and ankle deformity. This can lead to a fundamental etiological component of metatarsalgia, that being the repetitive loading of a locally concentrated force in the forefoot during gait.

Metatarsalgia is most often localized to the first metatarsal head. The next most frequent site of metatarsal head pain is under the second metatarsal. This can be due to either a short first metatarsal bone or a hypermobility of the first ray (metatarsal bone and the medial cuneiform behind it), both of which result in excess pressure being transmitted into the second metatarsal head.[2,3,4]

One or more of the metatarsal heads become painful and/or inflamed, usually due to excessive pressure. It’s common to experience acute, recurrent, or chronic pain with metatarsalgia. The pain is often caused from poorly fitted footwear, most frequently by high heel shoes and other restrictive footwear (Figure 1: Over-compression around the metatarsal heads can be related to metatarsalgia) [6]. Footwear with a narrow toe area forces the ball-of-foot area to be forced into a minimal amount of space (latero-medial over-compression). This can hamper the walking process and lead to extreme discomfort in the forefoot. [5,9]

Other factors that can cause excessive pressure are:

- Participating in high impact activities without proper footwear and/or orthotics

- Older age as the pad in the foot tends to thin out making it much more susceptible pressue and pain

- An imbalance in the length of the metatarsals

- Disturbances in gait

- Morphology of the foot (e.g. increased bone length that protrudes into the bottom of the foot)

- A shortened Achilles tendon

Forefoot pain may also be caused by conditions of the lesser toes, such as hammertoes, mallet toes, and claw toes. The pathophysiology of lesser toe deformities is complex and is affected by the function of intrinsic and extrinsic muscle units. In addition to lesser toe and metatarsal abnormality, forefoot pain can be attributed to interdigital neuritis, disorders of the plantar skin, and gastrocsoleus contracture.[2]

Norman Espinosa divided metatarsalgia into three categories in his review. He listed the various conditions associated with each subtype.

- Primary metatarsalgia refers to symptoms arising from innate abnormalities in the patient’s anatomy leading to overload of the affected metatarsal. According to Jesse F. Doty, metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the lesser toes (mainly due to plantar plate insufficiency) is also a common cause of metatarsalgia. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title - Secondairy metatarsalgia can be caused by systemic conditions such as arthritis of the MTP joint.

- Iatrogenic metatarsalgia can occur after (failed) reconstructive surgery.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Metatarsalgia typically affects the bottom of the second metatarsophalangeal joint. However, any of the other metatarsals can be affected. In more unusual cases, more than one metatarsal can be affected on one foot. When metatarsalgia affects the second metatarsophalangeal joint, it also sometimes referred to as “second metatarsophalangeal stress syndrome”.

Metatarsalgia is defined as pain in the anterior segment of the foot. Viladot stated that it is one of the most common types of pain. Symptoms of metatarsalgia include:

- Pain and tenderness of the plantar surface of the heads of the metatarsal bones or of the metatarsophalangeal joint

- Development of callus under the prominent metatarsal heads

- Increased pain during the mid-stance and propulsion phases of walking as body weight is shifted forward onto the forefoot.[3]

The pain is typically described as a deep bruise. Sometimes, it will feel like there is a rock under the ball of the foot. These symptoms are usually worsened when walking or standing barefoot on a hard surface or poorly cushioned shoe, and better when in well-cushioned shoes. At the end of a day, with substantial standing and/or walking, the area can throb.

When a patient reports forefoot pain, the first thing is to observe whether a callus is present. There may be tenderness over the plantar surface of the metatarsals, as well as the possibility of a depression on the dorsum over the head of the metatarsal bone. There may also be a decreased passive range of motion of the involved metatarsophalangeal joint. [4]

It is not uncommon to have a callus located under the affected metatarsal. Pain usually is first noticed at the bottom of the ball of the foot and there is no swelling. With progression, swelling can appear, along with tenderness at the top side of the joint. In some cases, bursitis will form adjacent to the metatarsal. In even more advanced cases, the joint capsule and ligaments on the bottom of the joint can wear-out and rupture, leading to the progressive development of a hammertoe. [5] Prof. Espinosa found that claw-toes with synovitis or even subluxation of the MTP joints were a common finding.[6]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

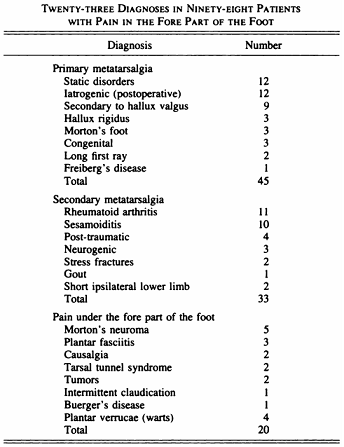

A study by Scranton (1980) of metatarsalgia in 98 patients revealed 23 distinct diagnoses. These diagnoses were grouped in three main headings: primary metatarsalgia, secondary metatarsalgia, and pain under the forefoot. The following table shows the different diagnoses divided under the three main catogories. [7]

Four of these diagnoses are mentioned below. Scranton divided metatarsalgia into structural, systemic, and miscellaneous forefoot pain categories. Structural and postoperative etiologies were the most common causes of forefoot pain; however, rheumatoid arthritis, Morton’s neuroma, and sesamoiditis were also relatively common. Although the greatest percentage of pain in the forefoot, especially under metatarsal heads, is caused by callosities, the most common of these diagnoses will be considered. [8]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

To differentiate one diagnosis from another, the use of the patient’s history, physical exam, roentgenograms, cholesterol-crystal force-plate analysis, intra-articular/digital injections and additional laboratory studies (electromyography, arteriograms, venograms,..) can be used.[9]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Foot Function Index (FFI) - The Brazilian-Portuguese version of the FFI questionnaire was found to be a valid and reliable instrument for foot function evaluation, and can be used both in scientific settings and in clinical practice. → Level of evidence: 2B[10]

- Foot Posture Index (FP1-6) - No scientific evidence found correlated to metarsalgia

- Manchester-Oxford foot questionnaire (MOxFQ) → Level of evidence: 4[11]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Look for evidence of systemic disease especially:

- diabetic neuropathy

- inflammatory arthropathy

- neurological disease

- vascular disease

Examination must begin proximally:

- any stiffness or deformity (including length discrepancy) which might alter pressures on the forefoot?

- tight Achilles tendon or reduced ankle dorsiflexion, especially if there is fixed equinus (remember to examine in subtalar neutral position)

- pes cavus

• overpronated foot with unstable 1st ray - peripheral neurological examination

- tenderness or a positive Tinel sign over the major nerve trunks

- hallux deformity or painful 1st MTPJ

- hammer or claw toes - if so, how flexible is the MTPJ. With the MTPJ reduced (if possible) is the fat pad reduced under the metatarsal heads?

- interdigital tenderness, palpable swelling or a positive metatarsal head compression test or Mulder's click

- interdigital corns

- tenderness and/or calluses under the metatarsal heads - check the relationship between the relative positions of heads and calluses. Most calluses are relatively diffuse although there may be increased thickening under the MT heads. However, a very localised callus should raise suspicions of a plantar condylar eminence

- metatarsophalangeal instability or irritability

- it is often possible to assess the relative heights and lengths of metatarsals by palpation

- look for scars of previous surgery

Always screen the patient for diabetes - a urine test is usually enough

This will usually indicate one or more possible factors which may be contibuting to forefoot pain. Differential injections around interdigital nerves and into MTP joints may help distinguish between MTP synovitis and interdigital neuralgia (although at least 10% of patients with each of these conditons also has the other) (Miller 2001). In the end it often requires experience-based judgement to decide which factors should be tackled and in what order. [12]

For second metatarsophalangeal joint instability, Dotty and Jesse F. devided the clinical staging of examination findings in 4 grades: [13]

- Grade 0: No MTP joint malalignment; prodromal phase with pain but no deformity

- Physical Examination Findings: MTP joint pain, thickening or swelling of the MTP joint, diminished toe purchase, negative drawer test result.

- Grade 1: Mild malalignment of MTP joint; widening of web space, medial deviation

- Physical Examination Findings: MTP joint pain, swelling of MTP joint, reduced toe purchase, mildly positive drawer test result (<50% subluxated).

- Grade 2: Moderate malalignment; medial, lateral, dorsal, or dorsomedial deformity, hyperextension of MTP joint

- Physical Examination Findings: MTP joint pain, reduced swelling, no toe purchase, moderately positive drawer test (>50% subluxated).

- Grade 3: Severe malalignment; dorsal or dorsomedial deformity; second toe can overlap hallux; might have flexible hammertoe

- Physical Examination Findings: Joint and toe pain, little swelling, no toe purchase (can dislocate MTP joint), flexible hammertoe.

- Physical Examination Findings: Joint and toe pain, little swelling, no toe purchase (can dislocate MTP joint), flexible hammertoe.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Unloading pressure to the ball-of-the-foot can be accomplished with a variety of footcare products. Orthotics designed to relieve ball-of-foot pain usually feature a metatarsal pad. The orthotic is constructed with the pad placed behind the ball-of-the-foot to relieve pressure and redistribute weight from the painful area to more tolerant areas. Other products often recommend include: gel metatarsal cushions, metatarsal bandages, NSAID’s, such as ibuprofen ; however, these agents rarely provide a long-term solution. NSAIDS are most commonly used for the relief of mild to moderate pain. But you have to use the right shoes. [4,7]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment is initially non conservative. The pressure on the forefoot can be reduced by stretching exercises to perform at the level of the lower limb, amounting. Also custom-made orthopedic insoles can reduce pressure.

Sometimes, in very specific cases, an infiltration, followed by taping a few weeks, brings some comfort, also some mobilization exercises are recommended. [2]

Gajdosic and coworkers demonstrated that a 6-week stretching program increased the maximal ankle dorsiflexion angle and length extensibility. They further demonstrated that stretching enhances the dynamic passive length and passive resistive properties. [14] - level of evidence 1b.

If these treatments have insufficient impact, surgery may be considered, depending on the defects, causes. In cases of hallux valgus or varus position, it should also be surgically corrected. The most common procedure is an osteotomy, where the metatarsal (one or more) responsible for the excess pressure, is shortenend or lifted. After surgery, one can basically rely on an immediate postoperative specifically designed shoe.[2,4,5]

Distal metatarsal osteotomies (such as The Weil osteotomy) provide a longitudinal decompression and is particularly relevant in patients suffering from metatarsalgia due to an excessively long metatarsal. One problem is the plantar translation of the metatarsal head during shortening. [15] - level of evidence 3a . Based on those results, Maceira and coworkers introduced the so-called “triple-osteotomy”. This modified osteotomy affords precise and accurate shortening of the metatarsal without unwanted plantar translation of the heads. The triple osteotomy also preserves the relationship between the dorsal interossei and transverse axis of rotation of the MTP joint to avoid an extension deformity. [16] - level 4 evidence.

The high pressure under the metatarsal heads can be reduced by applying metatarsal pads. In a double-blind study, tear-drop shaped, polyurethane metatarsal pads were applied by experienced physiatrists to a total of 18 feet. As a result, there were significantly decreased maximal peak pressures and pressure time intervals during exercise that correlated with better pain and function outcomes. [2,8]

Espinosa stated (with 2 clinical studies (level 2A evidence) and 1 retrospective study (level 2B evidence) as reference) that generally, accommodative insoles may redistribute pressure under the foot while functional orthoses are intended to control abnormal intersegmental motion. But both of them may be useful in the non-operative management of metatarsalgia.[17]

Not much scientific literature exists to confirm the effectiveness of these conservative treatment for the treatment of central metatarsalgia. Nevertheless, such measures often meet with success and have the additional benefit of not compromising future treatment [18]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8 (2008) - level of evidence: 1a

Resources[edit | edit source]

- The use of collagen injections in the treatment of metatarsalgia: A Case Report http://www.jfas.org/article/S1067-2516(10)00288-7/abstract

- Sports medicine - metatarsalgia http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/85864-overview

- J.Gregg, P. Marks (2007). Australasian Radiology: Metatarsalgia: An ultrasound perspective. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Pages 493-499.

- Associatie orthopdedie Lier http://www.associatie-orthopedie-lier.be/Generic/servlet/Main.html;jsessionid=B2F5539057DBEF99F23742666B6A844C?p_pageid=37247

- Foot and ankle institute http://voetenenkelinstituut.be/aandoeningen/voorvoet/metatarsalgie/

- Figure: http://www.sunnybrook.ca/uploads/metatarsalgia.jpg

7. Treatment & medication

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/85864-treatment

- Walter R. Frontera, Julie K. Silver, Thomas D. Rizzo (2008). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Elsevier Health Sciences. Pages 461-475.

- Metatarsalgia - forefoot pain http://www.sportsinjurybulletin.com/archive/metatarsalgia.html

References[edit | edit source]

1. Doty, Jesse F., and Michael J. Coughlin. "Metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the

lesser toes." The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 53.4 (2014): 440-445.

(level of evidence: 2a)

2.Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review:

metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8 (2008)

(level of evidence: 1a

3.G. McPoil Thomas and Schuit Dale. “Management of metatarsalgia secondary to

biomechanical disorders”. Physical Therapy 66(6): 970-2; July 1986

(level of evidence: 3c)

4. Sobel Ellen, D.P.M., Ph. D., C.PED. and Levitz Steven, D.P.M.; “Metatarsalgia : Diagnosis

and Manangement, Etiologies and Differential diagnoses”. Podiatry Management

(level of evidence: 5)

5 . Britt A Durham, Metatarsalgia Treatment & Management, medscape,2012

(level of evidence: 5)

6. W Yoo, Effect of the Intrinsic Foot Muscle Exercise Combined with Interphalangeal

Flexion Exercise on Metatarsalgia with Morton’s Toe, 2014, Pubmed

(level of evidence:3b)

7. Hashimoto T, Sakuraba K.: Strength training for the intrinsic flexor muscles of the foot:

effects on muscle strength, the foot arch, and dynamic parameters before and after the training. J

Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26: 373–376. ,pubmed

(level of evidence: 5)

8. Med Clin North Am. 2014 Mar;98(2):233-51. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.10.003. Epub

2013 Dec 10. Metatarsalgia, lesser toe deformities, and associated disorders of the forefoot.

(level of evidence: 4)

9. Gajdosik, RL, et al., A stretching program increases the dynamic passive length and passive

resistive properties of the calf muscle-tendon unit of unconditioned younger women. Eur J Appl

Physiol.

(level of evidence: 1b)

10. Maceira, E. et al, Analisis dela rigidez metatarso-falangica en las osteotomias de Weil.

Revista de Medicina y Cirugia del Pie.

(level of evidence: 3a)

12. Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8 (2008) (level of evidence: 2a)

13. G. McPoil Thomas and Schuit Dale. “Management of metatarsalgia secondary to biomechanical disorders”. Physical Therapy 66(6): 970-2; July 1986 (level of evidence: 3c)

14. Sobel Ellen, D.P.M., Ph. D., C.PED. and Levitz Steven, D.P.M.; “Metatarsalgia : Diagnosis and Manangement, Etiologies and Differential diagnoses”. Podiatry Management (level of evidence: 5)

15. Britt A Durham, Metatarsalgia Treatment & Management, medscape,2012 (level of evidence: 5)

16. W Yoo, Effect of the Intrinsic Foot Muscle Exercise Combined with Interphalangeal Flexion Exercise on Metatarsalgia with Morton’s Toe, 2014, Pubmed (level of evidence:3b)

17. Hashimoto T, Sakuraba K.: Strength training for the intrinsic flexor muscles of the foot: effects on muscle strength, the foot arch, and dynamic parameters before and after the training. J Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26: 373–376. ,pubmed (level of evidence: 5)

18. Med Clin North Am. 2014 Mar;98(2):233-51. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.10.003. Epub 2013 Dec 10. Metatarsalgia, lesser toe deformities, and associated disorders of the forefoot. (level of evidence: 4)

19. Gajdosik, RL, et al., A stretching program increases the dynamic passive length and passive resistive properties of the calf muscle-tendon unit of unconditioned younger women. Eur J Appl Physiol. (level of evidence: 1b)

20. Maceira, E. et al, Analisis dela rigidez metatarso-falangica en las osteotomias de Weil. Revista de Medicina y Cirugia del Pie. (level of evidence: 3a)

- ↑ http://www.eorthopod.com/content/foot-anatomy

- ↑ W Yoo, Effect of the Intrinsic Foot Muscle Exercise Combined with Interphalangeal Flexion Exercise on Metatarsalgia with Morton’s Toe, 2014, Pubmed

- ↑ G. McPoil Thomas and Schuit Dale. “Management of metatarsalgia secondary to biomechanical disorders”. Physical Therapy 66(6): 970-2; July 1986

- ↑ Sobel Ellen, D.P.M., Ph. D., C.PED. and Levitz Steven, D.P.M.; “Metatarsalgia : Diagnosis and Manangement, Etiologies and Differential diagnoses”. Podiatry Management

- ↑ Department of Foot and Ankle Surgery, Kaiser Medical Center, Santa Rosa; metatarsalgia http://www.permanente.net/homepage/kaiser/pdf/33070.pdf

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot &amp;amp;amp; ankle international 29.8 (2008)

- ↑ J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Jul;62(5):723-32. Scranton PE Jr; Metatarsalgia: diagnosis and treatment.

- ↑ Sobel Ellen, D.P.M., Ph. D., C.PED. and Levitz Steven, D.P.M.; “Metatarsalgia : Diagnosis and Manangement, Etiologies and Differential diagnoses”. Podiatry Management

- ↑ J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Jul;62(5):723-32. Scranton PE Jr; Metatarsalgia: diagnosis and treatment

- ↑ Martinez, Bruna Reclusa, et al. Validity and reliability of the Foot Function Index (FFI) questionnaire Brazilian-Portuguese version. 2016.

- ↑ Haque, Syed, et al. Outcome of Minimally Invasive Distal Metatarsal Metaphyseal Osteotomy (DMMO) for Lesser Toe Metatarsalgia. Foot & Ankle International. 2015.

- ↑ http://www.foothyperbook.com/elective/metatarsalgia/metatarsalgiaExam.html

- ↑ Doty, Jesse F., and Michael J. Coughlin. "Metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the lesser toes." The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 53.4 (2014):

- ↑ Gajdosik, RL, et al., A stretching program increases the dynamic passive length and passive resistive properties of the calf muscle-tendon unit of unconditioned younger women. Eur J Appl Physiol.

- ↑ Maceira, E. et al, Analisis dela rigidez metatarso-falangica en las osteotomias de Weil. Revista de Medicina y Cirugia del Pie.

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; ankle international 29.8