Lachman Test

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Admin, Evan Thomas, Ahmed Essam, David Adamson, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Tony Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Jonathan Wong, Alistair James, Ammar Suhail, WikiSysop, Kai A. Sigel and Wanda van Niekerk Alistair James

Purpose[edit | edit source]

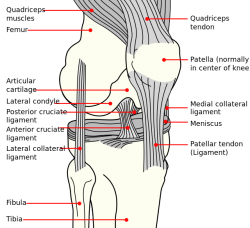

The Lachman test is a passive accessory movement test of the knee performed to identify the integrity of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The test is designed to assess single and sagittal plane instability.

Technique[edit | edit source]

Before testing the integrity of the ACL, the integrity of the PCL should be assessed first as a torn PCL will affect the results of the ACL test[1].

With patient in supine, place their knee in about 20-30 degrees flexion. This can be achieved through placing a towel under the patient's knee, or by the therapist placing their own knee on the bed under the patient's. According to Bates' Guide to Physical Examination, the leg should also be externally rotated slightly. The examiner should place one hand behind the tibia and the other on the patient's thigh. It is important that the examiner's thumb be on the tibial tuberosity. On pulling the tibia anteriorly, an intact ACL should prevent forward translational movement of the tibia on the femur ("firm end-feel").

Anterior translation of the tibia associated with a soft or a mushy end-feel indicates a positive test. More than about 2mm of anterior translation compared to the uninvolved knee suggests a torn ACL ("soft end-feel"), as does 10mm of total anterior translation. An instrument called a "KT-1000" can be used to determine the magnitude of movement in millimeters.

Technique Modification[edit | edit source]

The Stable Lachman test is recommended for examiners with small hands. The patient lies supine with the knee resting on the examiner’s knee. One of the examiner’s hands stabilizes the femur against the examiner’s thigh, and the other hand applies anterior stress. Adler and associates described a modification of this method, which they called the “drop leg Lachman test.” The patient lies supine. The test leg is abducted off the side of the examining table, and the knee is flexed to 25°. One of the examiner’s hands stabilizes the femur against the table while the patient’s foot is held between the examiner’s knees. The examiner’s other hand then is free to apply the anterior translation force. These researchers found that greater anterior laxity was demonstrated by this version of the test than by the classic version. The two legs are compared.[3]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Many systematic reviews have established the Lachman test to be the most sensitive test in the battery of ACL integrity tests[5], and also with the highest intra-rater and inter-rater reliability[6]. A systematic review of systematic reviews concludes that the Lachman test is the only test capable of ruling in and out an ACL injury by itself[7].

Katz and Fingeroth [8] reported that the Lachman test has a diagnostic accuracy of acute ACL ruptures (within 2 weeks of examination) of 77.7% sensitivity and >95% specificity. This study reported the diagnostic accuracy of subacute/chronic ACL ruptures (more than 2 weeks before examination) as having an 84.6% sensitivity and >95% specificity. It is important to note that in this study all examinations were performed under anesthesia, and therefore the diagnostic accuracy in physiotherapy clinical practice may be less.

Clinical Notes[edit | edit source]

Frank reported that to achieve the best results, the tibia should be slightly laterally rotated and the anterior tibial translation force should be applied from the posteromedial aspect. The hand on the tibia should apply the translation force[9].

With acute trauma, swelling prevents the examiner from getting a true indication of the joint’s mobility. The best time to assess joint laxity is immediately after the injury, before swelling occurs, or in the chronic state. The examiner may need to allow time for swelling to reduce before true joint mobility can be assessed.

Other special tests with the purpose of diagnosing ruptures of the ACL by testing its integrity include the knee anterior drawer test and the pivot shift test.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mulligan EP, Anderson A, Watson S, Dimeff RJ. THE DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF THE LEVER SIGN FOR DETECTING ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT INJURY. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1057-1067.

- ↑ Scott Holmes and Eric Sorenson, Lachmans Test, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bHytLhg-1vM, online video, last accessed 30 November 2009

- ↑ Adler GG, Hoekman RA, Beach DM. Drop leg Lachman test: a new test of anterior knee laxity. The American journal of sports medicine. 1995 May;23(3):320-3.

- ↑ CRTechnologies.Drop Leg Lachman Test (CR) . Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHgtxuoKNrE

- ↑ Prins M. The Lachman test is the most sensitive and the pivot shift the most specific test for the diagnosis of ACL rupture. Australian journal of physiotherapy. 2006;52(1):66–66.

- ↑ Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, Lützner J, Schmitt J, Kopkow C. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – A systematic review. Manual therapy. 2015;20(3):402–11.

- ↑ Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, Roy JS, Desmeules F. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Physical therapy in sport. 2017;23:143–55.

- ↑ Katz JW, Fingeroth RJ. The diagnostic accuracy of ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament comparing the Lachman test, the anterior drawer sign, and the pivot shift test in acute and chronic knee injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 1986;14:88-91. http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/14/1/88.short (accessed 18 July 2013)

- ↑ Frank C. Accurate interpretation of the Lachman test. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1986 Dec(213):163-6.