Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy

Original Editor - Melissa De Maeyer

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Mandeepa Kumawat, Mariam Hashem, Lisa De Donder, Melissa De Maeyer, Vanessa Rhule, Admin, Lotte De Clerck, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Oyemi Sillo, Kai A. Sigel, Rachael Lowe, HaniaElGibaly, Evan Thomas, Naomi O'Reilly and George Prudden

Description[edit | edit source]

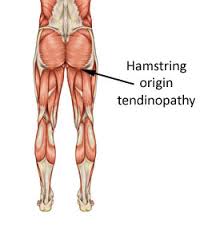

Hamstring origin tendinopathy, also called proximal hamstring tendinopathy or high hamstring tendinopathy, are a group of pathologies of the proximal hamstring tendon. They contain tendon degeneration, partial tearing and peritendinous inflammatory reaction.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

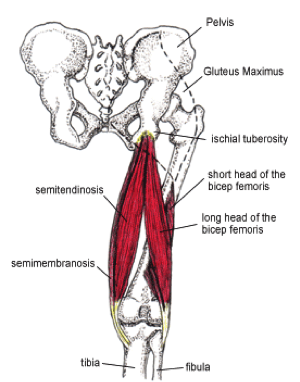

One of the most important muscle groups in running is the hamstring. They are active at multiple points in the gait cycle, namely the knee flexion and the hip extension.

The distal attachment is located on the top of your tibia, just behind the knee. The origin is divided in three branches, one starting from the femur and the two remaining ones starting from the ischial tuberosity. The junction between the tendons of the hamstrings and the ischial tuberosity is the area affected by high hamstring tendinopathy. The tendon’s thickness, fibrousness and poor blood supply is the cause of a difficult healing.[2]

The muscles of the hamstrings have a higher proportion of type 2 muscle fibers than the other muscles of the lower extremity. This suggests that these muscles can generate high intrinsic tension force. While running, the time increases that the hamstrings are under maximal stretch. The hamstrings and their tendon attachments have to endure heavy charges or high tensions because of these two forces, namely during eccentric contractions.[3]

(For extra information about pathology mechanisms see Tendinopathy)

Epidemiology / Etiology[edit | edit source]

Hamstring origin tendinopathy may arise after an acute tear at the origin that is not adequately treated. Still in most cases it’s a common overuse injury that is often seen in runners (more in middle- or long-distance runners than sprinters). It typically occurs with repetitive jumping, kicking and running activities. The hamstrings are prone to this type of injury as they contribute to the decelerating of the extension of the knee during activities such as sprinting and hill climbing. (Petersen J. et al, 2005)

The following factors can also increase the risk of hamstring origin tendinopathy:

Intrinsic factors:

- Malalignments

- Leg length discrepancy

- Imbalance

- Decreased flexibility

A study of stretching found that there are more hamstring problems with persons who didn’t stretch before participating in sports.[4]

- Joint laxity

- Female gender

- Age - When you get older, there is a reduction in muscle fiber size and number. This leads to a loss of mass and strength.[4]

- Overweight

- Proprioceptive weakness[5]

- Ischial tuberosity tenderness

- Core weakness

- Pelvic dysfunction[6]

- Previous injury - the strength is reduced by previous hamstrings, knee or groin injuries.[4]

- Neuromyofascial involvement- there is an increased neural tension and posterior thigh pain. There can be myofascial trigger points; this is associated with a decrease of flexibility.[4]

- Stiffness of the hip

- Tightness/Weakness of the hamstrings and quadriceps

- Bad pelvic/core stability.[7]

Extrinsic factors:

- excessive, repetitive load on the body

- training errors,

- environmental malconditions

- poor equipment

- Insufficient warming up - A warm-up with isometric contractions increases strength and length of the muscle.[4]

- Excessive training

- Fatigue - The muscle has less energy. There is also a lack of concentration, coordination and technique.[4]

Apparently core weakness and pelvic dysfunction seem to be closely related to the development of a hamstring tendinopathy.[6] The tendinopathy usually starts with micro-damage without a remarkable trauma. Normally the tendon is capable to intrinsic repair, meaning that the consequences of this injury are little. Sometimes, imbalance can cause further damage and failed healing. All of this leads to the formation of tendinosis. (Kannus 1997, Sharma and Maffulli 2005, Warden 2007.) Intrinsic and extrinsic factors contribute to the formation of this injury.[2]

Characteristics / Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Hamstring origin tendinopathy is related with deep buttock pain and pain in the posterior thigh. The pain is often felt in the lower gluteal region, radiating along the hamstings[6].

The pain increases while repetitive activity (such as long-distance running) and in worse cases pain is also mentioned while the person is sitting or driving a car. Usually there’s no acute trauma when the pain starts to appear, it gradually gets worse[8].

Continued exercises and stretching can cause even more pain[3].

Pain down the back of the thigh can be caused by irritation of the sciatic nerve. This nerve passes very close to the ischial tuberosity.[2] Due to its degenerative nature, this injury is classified as a tendinopathy rather than a tendonitis, an inflammatory pathology.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

First of all, it’s essential to determine if the pain is local or referred. If the patient says that the pain varies in location it will be referred pain. Pain in the buttock combined with pain in the lower back may refer to the lumbar spine. This may be caused by a problem with muscles, ligaments or disks.

If the pain is more local and constant it’s a pathology in the buttock itself. If the pain is located near the ischial tuberosity it may represent to hamstring origin tendinopathy or also ischiogluteal bursitis.

If the patient complains of higher pain (upper gluteal region) there might be a problem with the piriformis muscle.

Pain over the sacrum or near the sacroiliac joint refers to a pelvic stress fracture or inflammation or malalignment of the sacroiliac joint. There are also some uncommon cases where buttock and posterior thigh pain refer to chronic compartment syndrome of the posterior thigh. Due to the resemblance of some symptoms of this injury with other hip injuries, it’s important to get a proper diagnosis; this will likely entail a physical examination and an MRI.[3]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

An MRI is required to confirm the diagnosis and to take a look at the severity of the injury.

An MRI can recognize tendon thickening, tearing, inflammation and swelling at the tuber ishiadicum. You can also use ultrasound, but this technique isn’t able to give a precise visualization of bone marrow edema.[9]

Normally a high hamstring injury may be combined with stress reaction or bone edema in the ischial tuberosity and findings of the tendon. In case of a tendinopathy an increased signal is noticeable on T1-weighted images with no abnormalities on fat-suppressed T2-weighted images.[3][1]

However a series of provocation tests have been developed in order to help for the diagnose of this injury.

Pain provocation tests:

1) Palpation of the tuber ishiadicum

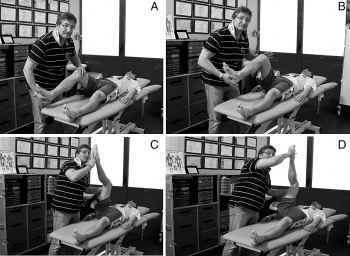

2) The Puranen-Orava test

This test is a standing stretch of the hamstrings, there must be a hip flexion of 90°. The foot rests on a support and the knee is in extension.

3) Bent-knee stretch test:

The test is performed while the patient is lying on his back. The hip and knee are maximally flexed. Slowly the therapist will straighten the knee till its maximal extension; the hip must remain in a 90° flexion. The test is also doable without the assistance of a therapist. The patient can use a rope or a belt to straighten his knee like depicted on the picture.

4) Modified bent-knee stretch test

The test is performed while the patient is lying on his back, the hip and knee are in extension. The therapist takes the heel in one hand and holds the knee with the other hand. He brings the hip and knee in maximal flexion and then rapidly straightens the knee.

These tests are used to identify a hamstrings origin tendinopathy, but do not replace an MRI.[2]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

A good flexibility of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles is a good prevention for this injury.

Some preventive techniques related to sport and hamstring injuries are to avoid block drills in the beginning of the season or on two following days.[9]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Anti-inflammatory drugs can help to deliver the irritated tissue around the tendon.[2]

In more severe cases, when physical therapy does not help, a corticosteroid injection into the peritendinous soft tissues is recommended, injecting the substance in the tendon itself can be dangerous. It’s important to know that this does not replace the therapy but it’s a part of the therapy. However, corticosteroid injections can also have a negative impact on the tendons inter alia the weakening of tendons, the rupture of tendons, particularly in load-bearing tendons (Kleinman M. et al, 1983). Frederickson et al. found that patients whose MRIs showed more swelling around the tuberositas ischiadicum and less thickening of the tendon got more relief from a cortisone injection than patients with more pronounced tendon thickening. A novel treatment is platelet-rich plasma injection at the origin of the muscle.[2] Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) seems to be a promising alternative to the corticosteroid injections. The alpha and dense granulates that are present in the platelets, release multiple growth factors and cytokines that promote wound healing (Alsousou J. et al, 2009 & Mishra A. et al, 2009). An enhancement of the recruitment, proliferation and differentiation of the cells involved in soft-tissue regeneration has been reported by the authors of in vitro studies (Hall MP et al, 2009, De Mos M. et al, 2008)

The shockwave therapy has almost no influence on hamstrings origin tendinopathies.[1]

When the conservative therapy doesn’t work, the patients need surgery to decrease the pressure on the nerve and to divide the fibrous and damaged tendon.[4]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

When a patient is diagnosed with hamstring origin tendinopathy, it’s usually preferable to consult a physical therapist. The earlier he starts with a physiotherapy treatment the faster he’ll return to his normal function. Normally this will take a couple of weeks but sometimes, when a patient has had hamstring origin tendinopathy for a longer period, it may take months to recover.[7]

The first thing a physical therapist will have to do is trying to control the pain. This occurs with ice, electrical stimulation of the tendon and pulsed ultrasound.

In the beginning of the treatment a misalignment of the pelvis has to be corrected because this might increase the tension in the hamstring muscles. It can also cause a decreased strength of the muscles. This misalignment is usually an anterior tilt of the pelvis and can easily be corrected by manual or chiropractic manipulation.

Soft-tissue mobilization has to be included in the rehabilitation program. It’s very beneficial to break up the adhesions and scar tissues. A friction treatment with transverse frictions is commonly used. The therapist has to pay attention to not compress directly the ischial tuberosity as it can irritate underlying edema. Techniques like ART (Active Release Technique) or Gastron can be included as well.

At the same time the patient may start a gradually built up stretching program for the hamstrings. This is also a crucial step in the process. Both legs should be stretched to have some balance. Even the antagonist hip-flexor muscles should be stretched for an optimal function. The RoM can be increased by the use of ultrasound or shockwave therapy before stretching. Frequent stretching may avoid a reappearance of the injury.

It’s important to regain strength in the muscle. First it’s best to begin with double-leg non weight-bearing isometric exercises followed by single-leg closed-chain isometrics and isotonic open-chain exercises. A good treatment for tendinopathies is an eccentric muscle strengthening program. This can normalize the thickness and structure of the tendon. It can also prepare the hamstrings for the high-force load while running. Glute bridges are interesting exercises to start a strength rehabilitation program with. Afterwards the patient can start with introductory exercises such as a standing ‘hamstring catch’. By using a Swiss Ball we can increase the difficulty of the exercise. As Frederickson et al stated, Swiss ball curl is ideal for development of both eccentric and concentric strength. According to the tolerance and the progression of the patient these Swiss ball curls can be practiced with short range of motion to full range of motion and eventually, single-legged Swiss ball curls.

Another point that must not be neglected is the importance of core strength. Core strength is a considerable element for the rehabilitation of hamstring origin tendinopathy as it reduces the risk of recurrent hamstring strains. As stated above a misalignment of the pelvis has to be corrected. By reinforcing the musculature of the abdomen and the hip the pelvis can be stabilized, taking strain of the hamstring. Plank exercises, especially with leg lifts incorporated are recommended by Frederickson who has conducted numerous studies about the rehabilitation of the hamstrings. Exercises like these encourage co-activation of the glute and hamstring muscles.

The previously mentioned exercises are considered as conservative treatments. More aggressive treatments are the ones including medical treatment such as injections or even surgery (see: Medical Management). Surgery is recommended for a resistance towards the conservative treatment. According to Puranen et al‘s study satisfactory results can often be expected. The main purpose of this intervention is to relieve tension on the sciatic nerve. As showed in the study of Lempainen (2009) the majority of the athletes are able to return to the same level of sport after receiving surgery of a high hamstring tendinopathy. As this sounds encouraging we must keep in mind that the average recovery time of five months is a quite long period when it comes to time off from running.[11]

If the RoM of the muscle is normal and pain-free, pool running and stationary biking could be put into the rehabilitation program.[12][8][3][4][13][14]

Running again:

High hamstring tendinopathy is known as a disease that takes a long time to recover from. Fredericson et al. estimates a recovery of 8-12 weeks. It’s likely that cross training doesn’t stress the legs until the bent-knee stretch test can be done without pain.

The moment that you can do the exercise shown on the picture below, you can begin with the return-to-running program described here:

Week 1: Walk 5min/jog 1min, build to sets on alternating days (ex. 2x5min/1min, off, 3x5min/1min, off, ect)

Week 2: If no pain, walk 5min/jog 5min, build to 5 sets on alternating days

Week 3: If no pain, advance to 20min jog, no more than 5 days per week

Week 4: If no pain, advance to 20min run at normal training pace, no more than 5 days per week

Week 5-8: If no pain, gradually increase running speed, volume, and acceleration as tolareted[2]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Maurice H. Zissen, et al. High Hamstring Tendinopathy: MRI and Ultrasound Imaging and Therapeutic Efficacy of Percutaneous Coorticosteroid Injection [Internet]. American Roentgen Ray Society 2010.Available from: http://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdf/10.2214/AJR.09.3674 Level of evidence 2B, grades of recommendation B

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 High hamstring tendinopathy injuries – Signs, symptoms and research-backed treatment solutions for a literal pain in the butt. Available from: http://runnersconnect.net/running-injury-prevention/high-hamstring-tendinopathy-injuries-a-pain-in-the-butt/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Michael Fredericson, et al. High Hamstring Tendinopathy in Runners. Meeting the Challenges of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Rehabilitation [Internet]. The Physician and Sportsmedicine 2005. Available from: http://www.agilept.com/downloads/high-hamstring-tendinopathy-in-runners.pdf - Level of evidence 2A, grades of recommendation B

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 P.BRUKNER & K. KAHN, clinical sports medicine, McGraw-Hill, Australia, 2005 (third edition), P388-390

- ↑ White, K. E., High hamstring tendinopathy in 3 female long distance runners. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2011, 10 (2), 93-99 Level of evidence 4. grades of recommendation C

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Fredericson, M.; Moore, W.; Guillet, M.; Beaulieu, C., High hamstring tendinopathy in runners: Meeting the challanges of diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2005, 33 (5), 32-43. Level of evidence 4, grades of recommendation C

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Tele Demetrious and Brett Harrop. Hamstring Origin Tendonitis. PhysioAdvisor 2008. http://www.physioadvisor.com.au/9628550/hamstring-origin-tendonitis-hamstring-injury-p.htm Level of evidence 5, grades of recommendation D

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Puranen J.; Orava S., The hamstring syndrome. A new diagnosis of gluteal sciatic pain, American Journal of Sports Medicine, 1988, 16(5): 517 – 521. Level of evidence 4, grades of recommendation C

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 McCormack R. J., The management of bilateral high hamstring tendinopathy with ASTYM treatment and eccentric exercise: a case report, The Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 2012, 20(3) 142 – 146. Level of evidence 4, grades of recommendation C

- ↑ Physiotutors. Bent Knee Stretch Test ⎟ Proximal Hamstring Tightness and Tendinopathy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xg0ghED6AS8

- ↑ Lempainen, L.; Sarimo, J.; Mattila, K.; Vaittinen, S.; Orava, S., Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy: Results of Surgical Management and Histopathologic Findings. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2009, 37 (4), 727-734. Level of evidence 3A, grades of recommendation B

- ↑ Reid, D.C., 1992. Sports injury assessment and rehabilitation. USA: Churchill Livingstone Inc. Pp. 415, 417, 554-570. Level of evidence 2A, grades of recommendation B

- ↑ Daniel Lorenz and Michael Reiman. The Role and Implementation of Eccentric Training in Athletic Rehabilitation: Tendinopathy, Hamstring Strains, and ACL Reconstruction [Internet]. Sports Physical Therapy Section 2011. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3105370/?tool=pubmed Level of evidence 2A, grades of recommendation B

- ↑ Mike Walden. Hamstring Origin Tendinitis / Tendinopathy. Sportsinjuryclinic.net 2011 http://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/cybertherapist/back/buttocks/hamstring_tendinitis.htm Level of evidence 5, grades of recommendation D