Ege's Test

Original Editors - Van Horebeek Erika

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Marlies Schils, Van Horebeek Erika, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Aarti Sareen, WikiSysop, Aminat Abolade, Claire Knott, Wanda van Niekerk, Evan Thomas and Vidya Acharya

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Ege's Test is also called the weight-bearing McMurray test because when patients perform this test, they have to put weight on their knees. Depending on the meniscus we want to investigate, the patient’s feet are turned outwards (medial meniscus) or inwards (lateral meniscus). [1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

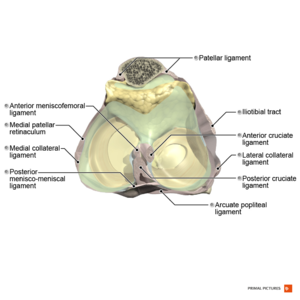

Articularis Genus consists of a number of anatomical structures, including the menisci. We have two menisci, a lateral and a medial. These cover the tibial articular surfaces.

The medial meniscus is larger than the lateral meniscus and has a C shape. This will combine with the Lig. Collaterale Mediale.

The lateral meniscus is smaller than the medial meniscus and has an O-shape. This is more mobile than the medial meniscus and will combine with the M. Popliteus [2]

Purpose[edit | edit source]

The purpose of the test is to detect a Meniscus tear on the medial or lateral side of the knee. [3][4][5][6][7][8]

Technique[edit | edit source]

Ege's test is performed in a standing position.

Start Position[edit | edit source]

- The knees are in extension

- The patient stands with feet 30-40cm apart

- Depending on the meniscus (medial or lateral) you are testing, the patient's feet are positioned to allow either maximum external rotation of the knee (medial meniscus) or maximum internal rotation of the knee (lateral meniscus). [9]

Test Movement[edit | edit source]

For Medial Meniscus tears, the patient squats with both lower legs in maximum external rotation and then stands up slowly. The distance between the knees increases and each knee becomes externally rotated as the squatting proceeds. [3][4][5][6] By performing the squat in maximum external rotation, genu varus will be induced (knees point outward). The patient squats as far as possible and then returns to the starting position (extension of the knee). [10]

To detect a Lateral meniscus tear, both lower extremities are held in maximum internal rotation of the knee while the patient squats and stands up. A complete squat in full Internal rotation is rarely possible, even for healthy knees, therefore the patient is allowed to steady himself/herself for a slightly less-than-full squat. In contrast to the medial meniscus test, the distance between the knees decreases and the knees become internally rotated as the squatting proceeds. [3][4][5][6] By performing the squat in maximal internal rotation, genu valgus will be induced (knees point inward). The patient squats as far as possible and then returns to the starting position (extension of the knee). [10]

Test Outcome[edit | edit source]

The test is positive when pain and/or a click is felt by the patient at the related site of the joint line. Further squatting is stopped as soon as the pain and/or click is felt, thus a full squat is not needed in all of the patients. Sometimes pain and/or click may not be felt until maximum squat or may be felt as the patient comes out of the squat, both of which are still considered positive for this test. Pain and/or click are typically felt at around 90° of knee Flexion. [3][4][5][6][7][8] [10]

Considerations[edit | edit source]

- It is important that during the test both feet stay on the ground.[10]

- It is important that the maximum rotation is maintained throughout the squat [10]

- These movements cannot be fully performed even by healthy people so first, it is important that the patient does not perform the squat fully to prevent pain exacerbation. Secondly, it is important that the patient use support if needed (e.g. on the treatment table). [10]

Anteriorly-located meniscal tears produce the symptoms earlier in knee flexion whereas tears located on the posterior horn of the menisci produce the symptoms in deeper knee flexion.

Flexion-extension and internal-external rotation components of the test are similar to that of McMurrays test. However, the most important difference is the weight-bearing position of the patient. Varus and valgus stress is also produced during internal and external rotation positions. [3]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

| N (Akseki et al.) |

effected side |

accuracy |

sensitivity |

specificity |

pos. liklihood |

neg. likelihood |

total % of wrong predictions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 211 |

med |

0,71 |

0,67 |

0,81 |

3,5 |

0,4 |

26% |

| lat |

0,84 |

0,64 |

0,90 |

5,3 |

0,5 |

21% | |

| M = 24% ± 2,55 |

[3][5][7]

According to Akseki et al. (B) the test correlated well to arthroscopic findings with a 0,341 kappa score. Akseki et al. compared diagnostic values of the Ege’s test with McMurray’s test and Joint line tenderness. There were no statistically significant differences found between the three tests in detecting a meniscus tear ( p > 0,05). However, for medial meniscus tears, Ege’s test scored better for accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity (respectively, 0,71, 0,67 and 0,81). For lateral meniscus tears, Ege's test gave results superior to the others: 0,84 accuracy, 0,64 sensitivity and 0,90 specificity. Ege’s test is more specific than sensitive. [3]

Looking at the different types of Meniscal tears, Akseki et al. found that degenerative tears of the medial menisci were missed in 66% (8 of 12!). Medial meniscal tears were diagnosed correctly with Ege’s test in 84% of cases, compared to only 61% with McMurray’s test. Similarly, Ege’s test was better at diagnosing longitudinal and bucket-handle medial meniscal tears.[3]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Two standard tests for a torn meniscus are McMurray's test and joint line tenderness (JLT). McMurray's test is done with the patient lying down. Ege's test is not possible to perform in every patient with a meniscal injury because of the weight-bearing requirements. This test must be performed keeping in view the balance and pain of the patient.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Akseki D, Özcan Ö, Boya H, Pınar H. A new weight-bearing meniscal test and a comparison with McMurray’s test and joint line tenderness. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2004 Nov 1;20(9):951-8.

- ↑ Richmond JC. Knee arthroscopy. McKeon BP, Bono JV, editors. New York: Springer; 2009 Apr 11.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Akseki D, Özcan Ö, Boya H, Pınar H. A new weight-bearing meniscal test and a comparison with McMurray’s test and joint line tenderness. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2004 Nov 1;20(9):951-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hegedus EJ, Cook C, Hasselblad V, Goode A, Mccrory DC. Physical examination tests for assessing a torn meniscus in the knee: a systematic review with meta-analysis. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2007 Sep;37(9):541-50.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Hing W, White S, Reid D, Marshall R. Validity of the McMurray's test and modified versions of the test: a systematic literature review. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2009 Jan 1;17(1):22-35.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Manish Pruthi MS DNB, Ravi K Gupta MS DNB MNAMS FIMSA, Akshay Goel MS. Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College Hospital, Chandigarh, India. Current concepts in meniscal injuries.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bossen D, Jurado M. The Accuracy of Physical Examination Techniques in Diagnosing Meniscus Lesions.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dan Lorenz, MS, PT, ATC/L, CSCS, KPTA Research Committee Member. Literature Review: CLINICAL TESTS FOR MENISCUS LESIONS.

- ↑ Hegedus EJ, Cook C, Hasselblad V, Goode A, Mccrory DC. Physical examination tests for assessing a torn meniscus in the knee: a systematic review with meta-analysis. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2007 Sep;37(9):541-50.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Blok BK, Cheung DS, Platts-Mills TF. First Aid for the Emergency Medicine Boards. McGraw Hill Education.; 2016.