Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Original Editors - Sarah Carlisle & Jill Thompson from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Sallie Rediske, Patrick Yoder, Sarah Carlisle, Vidya Acharya, Jill Thompson, Niha Mulla, Kim Jackson, Redisha Jakibanjar, Brock Ford, Admin, WikiSysop, Tony Lowe, Elaine Lonnemann, Wendy Walker, George Prudden, Rucha Gadgil, 127.0.0.1 and Rishika Babburu

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) is a debilitating and complex disorder that is not a single disease but the result of a combination of factors and is a subset of chronic fatigue. This is characterized by intense fatigue that is not improved by bed rest and that may be worsened by physical activity or mental exertion. This unexplained fatigue must last at least 6 consecutive months, must significantly interfere with daily activities/work, and the individual must concurrently demonstrate 4 or more of 8 specific symptoms.[1] There has been some difficulty in exactly defining CFS due to its very nature, and there have been multiple studies attempt to develop and finalize diagnostic criteria for CFS. [2] A Cochrane Review done in 2016 described CFS as an illness characterized by persistent, medically unexplained fatigue [with] symptoms that include severe, disabling fatigue, as well as musculoskeletal pain, sleep disturbance, headaches, and impaired concentration and short-term memory.[1][3]

CFS over the years has been known by various names such as chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome, chronic Epstein-Barr virus, myalgic encephalomyelitis, neuromyasthenia, as well as the, “yuppie flu”.[1]

CFS is characterized with overlapping symptoms (about 70%) with Fibromyalgia that have some biologic denominator.[4]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Reported prevalence is dependent on which definition/diagnostic criteria used, the type of population that was surveyed, and the study methods of the research being referenced. The Cochrane Review of 2016 reported estimates that between 2 in 1000 and 2 in 100 adults in the USA are affected by CFS.[3] Whereas other Goodman et all report studies finding prevalence among adults to be between 0.23% and 0.42% with higher incidence in women, minority groups, and people with lower educational attainment and occupational status.

- More common in women [1]

- Members of minority groups [1]

- Lower educational attainment and occupational status [1]

- Age range 29-35 years although all age groups can be affected [1]

- Illness duration ranges from 3-9 years. [1]

- Children developed CFS typically in the teen years although it was much less common [1]

- Research conducted by the CDC suggest that less than 20% of people with CFS have been diagnosed in the US. [1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Common reported symptoms:

- Fatigue [2] prolonged (lasting more than 6 months), overwhelming fatigue commonly exacerbated by minimal physical activity. [1]

- Exertional Malaise [2]

- Sleep Disturbance [2]

- Cognitive Impairment

- Decreased Concentration

- Impaired short term memory [2]

- Myalgia [2]

- Frequent or recurring sore throat [1][5]

- Fever (common at onset) [1]

- Muscle Pain [1][5] (common at onset)

- Muscle Weakness (common at onset)

- Multiple Joint Pain [5] without swelling or redness [1]

- Neurally mediated hypotension (NMH) (May experience lightheadedness, lower blood pressure and pulse, visual dimming, slow response to verbal stimuli) [1]

- Tender lymph nodes in neck or armpit [1][5]

Chronic Fatigue Vs. Tiredness: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEcd0KxfVOM[6]

Prognosis:

- CFS will vary from person to person but will often follow a course, alternating between periods of illness and relative well-being. Some people may experience partial or complete remission of symptoms; however, they often reoccur. [1]

- Recovery rates can be unclear, depending on the study, improvement rates vary from 8% to 63% with a median of 40% of people improving during follow up. [1]

- Full recovery may be rare, with an average of only 5-10% sustaining total remission. [1]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- Neurally mediated hypotension (NMH) is a common finding in individuals with CFS. Individuals with NMH have a low blood pressure and heart rate; thus, they can experience syncope, visual dimming, or a slow response to verbal stimuli. [1]

- Anxiety [7][8]

- Depression [7][8][9] Connection between immuno-inflammatory and TRYCAT pathways and physio-somatic symptoms. [8]

- Fibromyalgia [1][8][10]

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome [8][9]

- Myofascial pain syndrome [8]

- Temporomandibular joint syndrome [8]

- Interstitial cystitis [8]

- Raynaud's phenomenon [8]

- Prolapsed mitral valve [8]

- Migraine [8]

- Allergies [8]

- Multiple chemical sensitivities [8]

- Sicca syndrome [8]

- Obstructive or central sleep apnea [8]

Medications[edit | edit source]

While studies have investigated the use of various medications, none have been found to have consistent results. However, the following drugs are used to address and manage symptoms [6]:

- Medications to reduce pain, discomfort, and fever

- Medications to treat anxiety

- Medications to treat sleep disturbance (amitryptyline, nefazodone [1])

- Modafinil [2]

- Medications to treat joint pain (amytryptyline [1])

- Medications to treat depression (sertralin, paroxetine, nefazodone [1])

- Anti-inflammatory drugs (aspirin, acetaminophen [1])

- NSAIDS to address headache relief [1]

- Rintatolimod improved measures of exercise performance compared with a placebo (low strength of evidence) [4]

- Deydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) was found in a pilot study to significantly reduce the pain, helplessness, anxiety, thinking, memory, and activities of daily living difficulties associated with CFS; however, further research is necessary. [1]

- Based on current evidence corticosteroids cannot be recommended for CFS due to complications of long-term use. Mineralcorticoids and Intravenous Immunoglobulin are not recommended either and need further research. [1]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Currently there are no specific tests available that identify CFS. One study reports that patients with CFS have demonstrated abnormal white blood cell count and brain MRI results. [6] Goodman suggests that physicians rule out other diagnoses (from list below: Differential Diagnosis) and make use of the CDC’s criteria to determine if an individual has CFS. [1] The CDC’s criteria are: [1][5]

1. Clinically evaluated, unexplained persistent or relapsing chronic fatigue that is any of the following:

- New or definite onset

- Not the result of ongoing exertion

- Not substantially alleviated by rest

- Results in substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities

2. The concurrent occurrence of 4 or more of the following symptoms:

- Substantial impairment in short-term memory or concentration

- Sore throat

- Tender lymph nodes

- Muscle pain

- Multiple arthralgias (joint pain) without swelling or redness

- Headaches of a new type, pattern, or severity

- Unrefreshing sleep

- Post-exertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours

The symptoms must have persisted or recurred during 6 or more consecutive months of illness and must not have predated the fatigue. [1]

Sixteen gene abnormalities have been found in individuals with CFS, some related to immunity and defense; however, further research is needed to determine just how gene expression might effect those with CFS. [5]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

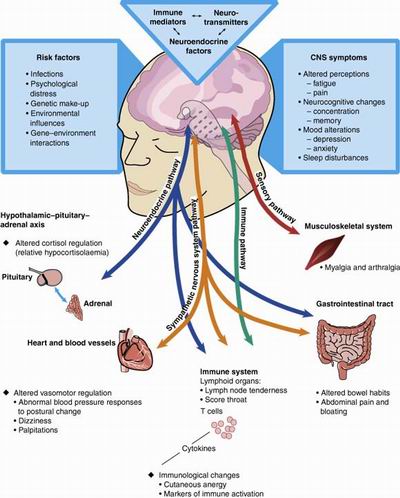

- The etiology and pathophysiology remain unknown. [1][5][8] Several attempts in research have been made to investigate the etiology, causes, and pathogenesis of CFS. Earlier theories focused on the prominence of symptoms that suggested an acute viral illness or a psychiatric disorder. Other theories have documented abnormalities including brain structure and function, neuroendocrine responses, sleep architecture, immune function, virological studies, exercise capacity, and psychological profiles. [1]

- CFS involves complex interactions between regulating systems and seem to involve both the central and peripheral nervous systems, the immune system, and the hormonal regulation system. The etiology and pathogenesis is believed to be multi-factorial. [1]

- Recent infection (cold, flulike illness) [1]

- High rates after a fever and Lyme disease [1]

- Personality characteristics of neuroticism (instability, anxiety, aggression)

- Introversion

- Acute physical or psychologic stress (trigger)

- Stressful life events (loss of a loved one or a job)

- Studies suggest that physiological and psychological factors need to both be addressed when working with an individual with CFS to better treat the illness. [5]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Neurological

- Symptoms reported by chronic fatigue syndrome patients-including fatigue; impaired concentration, attention, memory; and headache. [8]

- Decline in grey matter volume due to decrease in physical activity. [8][1]

- Volume changes and problems in the integrity of white matter. [8][1]

- Defective serotonergic signaling in the brain at or above the hypothalamus. Specifically, in relation to the 5-HTT gene demonstrating promoter polymorphism. [8][1]

Endocrine

- Research suggests abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and serotonin pathways, suggesting an altered physiological response to stress. [8]

- Abnormal cortisol secretion which correlates with health and physical function. [8][1]

Immune System

- Poor natural killer cell cytotoxicity (natural killer cell function, not number) [8]

- Although immune dysfunction is common in patients with CFS it is not specific to CFS [8]

http://www.medicalook.com/Nutritional_supplement/Chronic_Fatigue_Syndrome.html [3]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

First, other common conditions should be ruled out prior to diagnosis. See Differential Diagnosis section for details.

There is no known cure for CFS, therefore focus is aimed at symptom relief and improved function. A combination of drug and nondrug therapies is recommended. However, no single therapy has proven to help all individuals with CFS. [1]

Focus on lifestyle changes:[1]

- Prevention of overexertion

- Reduced Stress

- Dietary restrictions

- Gentle Stretching

- Nutritional supplementation

Drug Therapy to address:[1]

- Sleep disturbances

- Pain

Systematic Reviews have shown effectiveness and benefits with cognitive behavior therapy and graded exercise therapy.[1]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy begins by assessing the patient’s current health status to see if signs of deconditioning exist. If so, Goodman suggests starting with a strengthening program and then progressing to activities that test the cardiovascular system. [1] Physical therapy management of CFS is focused on progressing from minimal activity to 30 minutes of continuous exercise during periods of remission, [1]always focusing on gentle, graded, flexible exercise that is monitored continuously [5] Goodman suggests monitoring vital signs and assessing fatigue levels using a 5-point scale during exercise and activities. [1] Education about the syndrome, the importance of exercise, and how to pace oneself in everyday activities to avoid fatigue and relapse is a key component in the management of CFS. [1]One study states that due to the necessary and unique components of helping individuals manage chronic fatigue, physical therapists need to be trained on how to both deliver pain management and exercise programs to these individuals. [5]

Graded exercise therapy (GET) has been shown to be a more effective treatment option than stretching and relaxation exercises for individuals with CFS, while all the above options are important aspects of care for the individual. [1] GET, along with counseling and behavioral therapies, has shown improvements in measures of fatigue, function, global improvement, and work impairment. [5] GET, when combined with CBT, had greater success in reducing fatigue and improving physical function than did adaptive pacing therapy (APT) or specialist medical care (SMC) alone. While APT encourages adaptation to illness, CBT and GET encourage gradual increases in activity with the aim of ameliorating the illness. [7] GET results are still variable (see chart below [5]) and will benefit from further research to determine effects on individuals with CFS. [5]

According to the European Journal of Clinical Investigation in regards to Exercise Guidelines for Patients with CFS, there are four subgroups of the parameters considered in the GET and CBT interventions. These include time- or symptom-contingency, exercise frequency, exercise modality, and home exercises. A time-contingent approach to exercise therapy for patients with CFS is superior over the symptom-contingent approach. As for exercise frequency, available studies point towards a treatment of 10-11 sessions of 4-5 months. Exercise modalities that are most appropriate for people with CFS are aerobic in nature. This might include activities such as swimming, biking, and especially walking. Strength, balance, and stretching activities could be added to aerobic exercise, however, as a stand-alone-treatment, these interventions are ineffective. Home exercise should, based on the evidence, consist of 5 exercise bouts, starting for a duration between 5 and 15 minutes, gradually increasing to 30 minutes. See chart below for a visual depiction of the current evidence. [8]

Chart summarizing the clinical messages: exercise therapy for people with chronic fatigue syndrome. [8]

Isometric yoga is another possible treatment method for those with CFS. It along with conventional therapy was more effective in relieving fatigue than was conventional therapy alone in patients with CFS who did not respond adequately to conventional therapy. The results of this study suggested that an isometric yoga program is both feasible and acceptable for patients with CFS. The results also indicated that isometric yoga can significantly improve fatigue, enhance vigor, reduce pain, and improve quality of life. [9]

Psychological Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) has emerged as a treatment option for those with CFS. General improvements have been reported in fatigue, pain, and social adjustment. [5][1][10] CBT involves enabling individuals to develop a consistent approach to activity, gradually increase activity, develop healthy sleep patterns, and identify and challenge unhelpful cognitions. [10] CBT is one of the few non-pharmacological management techniques recommended for individuals with CFS [5]; however, it, too, has had mixed results. If an individual is experiencing high levels of pain, Marshall suggests other treatment strategies be used in combination because CBT is aimed more specifically at managing fatigue levels. [5] CBT is an individualized, proactive approach on the patient’s part, involving self-reflection and monitoring in the hopes of discovering what kinds of behaviors or thoughts are causing the CFS symptoms. [1][10] CBT also involves learning coping strategies and initiating a daily schedule of rest and activity in order to address fatigue levels and optimize function.[1] According to Stahl, Rimes, and Chalder, there should be a greater emphasis placed on behavioral change in the early stages of treatment, which may result in greater subsequent cognitive change and superior treatment outcomes. [10]

Roberts found that individuals with hypocortisolism and CFS do not respond as well as others after 12-15 sessions of CBT. [6] The study questions if these individuals require a longer duration of CBT, a modified version, or a combination of therapies including hydrocortisone replacement therapy. [6] Further studies are necessary in order to address these questions.

Due to some of the limitations of CBT as an effective treatment option for patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, researchers looked to evaluate the effectiveness of CBT versus a multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment. It has been noted that patient with CFS who reported a higher frequency of weight fluctuations, physical shaking and pain, who were more symptom focused and anxious had a poor CBT outcome compared to other patients. [1] Therefore, other treatment options must be considered to aid in the rehabilitation of this population. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment might include CBT and other different strategies such as gradual reactivation, pacing, mindfulness, body awareness therapy, normalization of sleep/wake rhythm and social reintegration. [1] Vos Vromans et al found that multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment is more effective in sustaining the decrease in fatigue severity and that patients are more satisfied with the results at 52 weeks compared to CBT. [1]

See Physical Therapy Management for information regarding combination of GET and CBT.

Self Management[edit | edit source]

Marshall [5] stated that in their study, individuals with CFS reported trying to self-manage their symptoms in addition to physical therapy or alternative techniques. Self-pacing, stretches, breathing exercises, and yoga were among the kinds of activities reported; with stretches and breathing exercises managing pain levels the best (see chart below). [5]

For more information on the benefits of yoga for individuals with CFS, see Physical Therapy Management.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following are possible differential diagnoses: [1][8]

- Fibromyalgia: Patients with Fibromyalgia usually present with increased pain, while patients with CFS experience greater fatigue.

- Mononucleosis

- Lyme Disease

- Thyroid conditions

- Diabetes

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Various Cancers

- Depression

- Bipolar disorder

Case Reports/ Case Studies

[edit | edit source]

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Case Report: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3028106/ [2]

- 39-year-old female, previously healthy, developed mononucleosis with typical symptoms and findings.

- Lab tests were diagnostic of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

- Fatigue worsened, was not relieved by rest, and eventually was so severe that the patient became bedridden and unable to work.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome was diagnosed at one clinic and later confirmed at another.

- While levels of complement split products were elevated, the patient remained chronically and severely fatigued.

- Once compliment split products normalized, the patient had complete resolution of symptoms of CFS and returned to work.

“Doctor, I’m so tired!” Refining your work-up for chronic fatigue. [4]

- 35 year old female presents to your clinic complaining of fatigue that started 8-months ago and has gotten progressively worse.

- Sleeps really well on the weekends, but typically gets less than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week. Regardless of the hours of sleep she gets, she never wakes up feeling refreshed.

- She reports being too tired to exercise.

- Although she has a strong network of family and friends, she does not have energy for socializing.

- She ends up being referred for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and is scheduled to return in 4-weeks.

- Patient implements healthy lifestyle changes recommended by healthcare providers to sleep greater than 7 hours each night and eat a healthy diet. Patient also started a walking program, eventually reaching 3 hours of walking each week.

- 4-weeks after lifestyle changes, she implements a weekly resistance training program.

- Patient intentionally increased her social activities.

- 6-months after initial visit, patient reports significant improvement although she is still fatigued more easily than most people.

The Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Depression and Low Self-Esteem in the Context of Pediatric Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS/ME): A Case Study. [3]

- 16 year old female diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome.

- After being diagnosed, some of her early experiences and critical incidents were noted to lead to assumptions and general beliefs of herself.

- These general beliefs showed evidence of triggers that caused changes in her thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Unhelpful and helpful coping strategies were noted.

- These different characteristics were considered when creating a plan of care with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

- Based on this study, CBT may be useful when working with young people with chronic fatigue syndrome and mood difficulties.

- See study for more specific details regarding evaluation methods and plan of care.

What happens when you have a disease doctors can’t diagnose? – Jennifer Brea: https://www.ted.com/talks/jen_brea_what_happens_when_you_have_a_disease_doctors_can_t_diagnose [5]

- Jennifer Brea shares her experience with chronic fatigue syndrome from the beginning of her symptoms, through the journey of being diagnosed, to the life she now lives with her condition.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Support Group & CFS Information: http://www.chronicfatiguesyndrome.me.uk/ [7]

Physical Therapist’s Guide to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=13f232c1-2d06-4063-8a3b-5ae844fdd075 [8]

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome a ‘Real’ Disease in Need of a New Name and Diagnostic Criteria, Says IOM http://www.apta.org/PTinMotion/News/2015/2/12/ChronicFatigueIOM/ [9]

Treating Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): The IACFS/ME Conference Overviews Part V https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2017/02/15/treating-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-mecfs-iacfsme-conference-overviews-part-v/ [10]

Chronic Fatigue Vs. Tiredness: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEcd0KxfVOM [6]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 1.47 1.48 1.49 1.50 1.51 1.52 1.53 1.54 1.55 1.56 1.57 1.58 1.59 Goodman CC., Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Haney, E. et al. Diagnostic Methods for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Systematic Review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Annals of Internal Medicine. June 2015:162(12), 834-841.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Larun, L. et al. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016:(12). DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003200.pub6

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists Screening for Referral. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Inc; 2013.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 Marshall, R BSc (HONS), Paul, L PhD, Wood, L PhD. The search for pain relief in people with chronic fatigue syndrome: a descriptive study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2011:27(5);373-383. Available from: PubMed.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Teitel AD MD MBA, Zieve D MD MHA. Chronic fatigue syndrome. PubMed Health: A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. 2012. Available from: PubMed.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Cella, M., White, PD., Sharp, M., Chalder. T. Cognitions, behaviours and co-morid psychiatric diagnosies in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychological Medicine. 2013 (43). 370-380. DOI 10.1017/S0033291712000979

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome:Redefining an Illness Washington,DC: National Academies Press (US); 2015 Feb 10.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Anderson, G. et al. Biological phenotypes underpin the physio-somatic symptoms of somatization, depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome. Aeta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2014:83-97.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Snell, C. R. et al. Discriminative Validity of Metabolic and Workload Measurements for Identifying People with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Physical Therapy Journal. November 2013:93, 1484-1492.