Calcaneal Spurs: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Evan Thomas (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 220: | Line 220: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /><br> | |||

[[Category:Conditions]] [[Category:Sports_Injuries]] [[Category:Foot]] [[Category:Bones]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | |||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project | |||

Revision as of 07:06, 6 January 2017

Original Editors - Caro De Koninck

Top Contributors - Mahyar Firouzi, Lionel Geernaert, Julie Lhost, Ivakhnov Sergei, Caro De Koninck, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Scott Cornish, Admin, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Joao Costa, Evan Thomas, Naomi O'Reilly, Priyanka Chugh, Wanda van Niekerk and 127.0.0.1

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Search words:

Calcaneal

Calcaneal spur

Heel spur

Heel pain

Plantar fasciitis

Bony spur

Calcification plantar fascia

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

A calcaneal spur, or commonly known as a heel spur, occurs when there is a bone spur (a bony outgrowth) formed on the heel bone. Calcaneal spurs can be located at the back of the heel (dorsal heel spur) or under the sole (plantar heel spur). The dorsal spurs are often associated with achilles Tendinopathy, while spurs under the sole are associated with Plantar fasciitis.

The apex of the spur lies either within the origin of the planter fascia (on the medial tubercle of the calcaneus) or superior to it (in the origin of the flexor digitorum brevis muscle). The relationship between spur formation, the medial tubercle of the calcaneus and intrinsic heel musculature results in a constant pulling effect on the plantar fascia consequent a inflammatory process.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

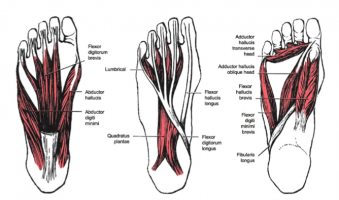

M. Soleus

M. Gastrocnemius

M. Plantaris

M. Abductor Digiti minimi

M. Flexor digitorum brevis

M. Extensor digitorum brevis

M. Abductor hallucis

M. Extensor hallucis brevis

M. Quadratus plantae

Plantar fascia

All of these structures are in a position to exert a traction force on the tuberosity and adjacent regions of the calcaneus, especially when excessive or abnormal pronation occurs. The origin of the spurs appears to be repetitive trauma that produced microtears in the plantar fascia near its attachment and the attempted repair led to inflammation which is responsible for the release and the maintenance of the symptoms.[2][3][4][5]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of the spur has been debated. At the beginning of the twentieth century, gonorrhea was considered a prime ethiological factor. Heredity, metabolic disorders, tuberculosis, systemic inflammatory diseases and many other disorders have also been implicated. Now abnormal biomechanics (excessive or abnormal pronation) enjoys wide support as the prime etiological factor for the painful plantar heel and the inferior calcaneal spur. The spur is thought to be a result of the biomechanical fault and an incidental finding when associated with the painful plantar heel.

The most common etiology involves abnormal pronation with resultant increased tension forces developed in the structures attaching in the region of the calcaneal tuberosity.

Asymptomatic heel spurs are relatively common in the normal, adult population. One epidemiologic study found that 11% of the adult U.S. population demonstrated a calcaneal spur as an incidental radiographic finding.[6]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The painful heel is a relatively common foot problem but calcaneal spurs are not considered a primary cause of heel pain. A calcaneal spur is caused by long-term stress on the plantar fascia and muscles on the foot and may develop as a reaction to plantar fasciitis.[7]

The pain, mostly localised in the area of the medial process of the calcaneal tuber, is caused by pressure in the region of the plantar aponeurosis attachment to the calcaneal bone. The condition may exist without producing symptoms, or it may become very painful, even disabling.[8]

Most heel pain patients are middle-aged adults. Some of them are obese, so obesity can be considered a risk factor. Not all heel spurs cause symptoms and are often painless, but when they do cause symptoms people often experience more pain during weight-bearing activities, in the morning or after a period of rest. The experienced pain, however, is not the result of pressure of weight on the top of the spur but comes from an inflammation around tendons where they attach to the bone.

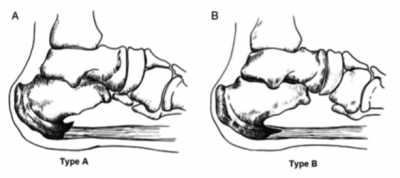

Two types of calcaneal spurs may be distinguished. Type A spurs are superior to the plantar fascia insertion, and type B spurs stretch forward from the plantar fascia insertion to extend distally within the plantar fascia.

The mean spur length for type A calcaneal spurs is significantly longer statistically than the mean spur length for type B spurs, while patients with type B spurs reported more severe clinical pain.[9]

Differently, spurs can be classified into three types:

- There are those which are large in size but are asymptomatic, because the angle of growth is such that the spur does not become a weight-bearing point and/or the inflammatory changes have been arrested.[10]

- Secondly, there are those which are large as well as painful upon weight-bearing, because the pitch of the calcaneus has been changed by a depression of the longitudinal arch and, as a result, the spur may become a weight-bearing point, sometimes causing intractable refractory pain.[10]

- Lastly, there are those which have only a rudiment of proliferation and whose outline is irregular and jagged, usually accompanied by an area of decreased density around the origin of the plantar fascia, indicating a subacute inflammatory process. All calcaneal spurs undoubtedly begin in this manner, but only a few become symptomatic at this stage, because the etiologic factors are acute.[10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Because chronic heel pain is a common manifestation of many conditions, these must be excluded before planning treatment. Medical (diagnostic) imaging as well as medical signs are often used to differentiate some of the conditions that are mentioned below from calcaneal spurs.

1. Musculoskeletal causes:

- Peroneal tendonitis: (inflammation of one or both peroneal tendons)

MRI scan (level 3B) or ultrasound investigation (level 4).

- Haglund's deformity(with or without bursitis): (symptomatic osseous posterior-superior prominence of the calcaneus)

Radiographs or Sonography of foot in maximal dorsiflexion (level I).[11]

- Sever's disease(calcaneal apophysitis): (inflammation of the calcaneal apophysis due to overloading)

Clinical[12] (level 3B), ultrasonography[13] (level 4).

2. Traumatic influences:

- Calcaneal fractures (and stress fractures): (fractures as a consequence of repetitive load to the heel)

Ottawa Ankle Rules, Radiography, MRI (isotopic bone scan) and ultrasound.[14]

3. Neurological causes:

- Baxter nerve entrapment: (chronic compression of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve)

Clinical (Tinel’s sign) (level 2A).

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome (sinus tarsi): (Impingement of the posterior tibial nerve)

Clinical (Tinel’s sign, dorsiflexion-eversion test) (level 1B).

4. Other:

- Heel fat pad syndrome: (Atrophy or inflammation of the shock-absorbing fatty pad or corpus adiposum)

Clinical, ultrasound scan (level 1B).

- Chronic lateral ankle pain with other cause:

MRI (level 4).

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is based on the patient's history and on results of the physical examination. The suspicion diagnose is confirmed mostly in the X-ray on the calcaneus, but diagnostic adjuncts are available to assist the clinician.[15] Radiology may demonstrate calcaneal spur formation or calcification at either the insertion of the Achilles tendon or the origin of the plantar fascia.[16]

Rarely MRI may be required.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)

Examination[edit | edit source]

There are different aspects that need to be taken in consideration when performing the clinical examination.

- Is there a limitation in range of motion in the ankle and foot?

Spend more attention to passive dorsiflexion in the toes.

Video : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QsCmuO37-aA

- Palpation of the plantar fascia end heel. The presence of the calcaneal spur, any tenderness (site/severity) or deformities can be felt (in combination with the dorsiflexion in the ankle)

- Is there any atrophy of the heel pad in compare with the other foot in combination with reduced muscle strength?

- Is there any swelling?

- Sensation

→ Hypesthesias/dysthesias? (tibial nerve) → Tinel’s sign

- Are there any skin tears on the foot?

- Any difference in foot-alignement in compare with the other foot?

→ Weight-bearing

- Evaluation of the gait

Management

[edit | edit source]

‘The clinical practice guidline revision 2010’ mentions different phases in revalidation, divided in ‘tiers’. We need to take into account the fact that it’s difficult to differentiate the cause of complains on the dorsal side of the heel. That is the reason a plantar heel pain treatment ladder may be used for treating heel pain complains.

If a certain tier reduces complains, the therapy should go on. If there is no improvement noticed, the therapist needs to move on to a higher tier in the treatment.

Tier 1: Effect in <6 weeks

Tier 2: Effect in about <6 months

Tier 3: Effect in >6 months

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Tier I

● Non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAID)[17]

→ Grade I recommendation

● Cortisone injections[18]

→ Grade B recommedation

Tier II

● Repeat cortisone injections[19][20][21]

→ Grade B recommedation

● Botulinum toxin[22][23][24]

→ Grade I recommendation

Tier III

● Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy[25]

● In-step fasciotomy[26][27]

● Minimal invasive surgical technique

→ All grade B recommendation

Non Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Tier I

● Padding & strapping of the foot[28][29]

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jKGDhxcdtzE

● Therapeutic orthodic insoles for short-term painrelieve[30][31]

● Achilles & plantar fascia stretching[32][33]

Video : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hauyuX-uCq8

→ All grade B recommedation

Tier II

● Prefabricated and custom orthodic device

prefabricated shows better results compared to the custom device in the improvement of symptoms [34]

→ Grade B recommedation

● Night splints[35]

→Grade B recommedation

●Physiotherapy[36]

→ Grade I recommedation

● Cast or boot immobilisation[37]

→ Grade C recommedation

Tier III

● ESWT (Extracorporal Shock Wave Therapy)[38][39][40][41]

→ Grade B recommedation

● Bipolar radiofrequency (microtenotomy)[42]

→ Grade C recommedation (2010)

Missing Evidence In The Guidlines

[edit | edit source]

1) We need to take into account that some treatments are proven effective in treating “fasciitis plantaris”, but not in the presence of calcaneal spurs.We can conclude that those recommendations can only be used when the calcaneal spur is associated with fasciitis plantaris.

2) Bipolar radiofrequency (microtenotomy) :

In the guidline, this treatment received a grade C recommendation. This grade may change in the future due to new research.

- March ‘15: “Bipolar radiofrequency microtenotomy appears to be a safe procedure that can provide outcomes equivalent to those with open surgery, with less morbidity, for recalcitrant plantar fasciitis.” [43] (Level of evidence : 3)

- December ‘15: “RM is as effective as PF in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Patients who underwent both procedures experienced no benefit and a higher rate of complications.” [44] For long-term efficacy a larger research scale is needed.

3)‘Low level laser therapy’ is found to be an effective method for treating heel spurs. More research with larger groups is needed for more evidence.[45]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Calcaneal spurs, both upper and lower spurs, are treated with conventional physiotherapy.

● Low Dose Radiotherapy (side effects : radiation side effects and syndromes)

Using this method, there is evidence that the re-irritation of the painful heel spur syndrome is a safe and effective treatment. There was a significant response for at least 2 years in reduction of pain (level of evidence: 2B)[46]. A placebo effect can occur (level of evidence : 1B)[47]. There is still no clear decision what dose is the most effective (1.0 Gy or 0.5 Gy).

● Cryoultrasound therapy and cryotherapy are both effective for treating chronic plantar fasciitis with heel spurs. Cryoultrasound therapy seemed to be better. (level of evidence : 1B)[48]

● Thermotherapy

1)Cold therapy may be used to relieve inflammation and numb pain.

2)Heat therapy to loosen tense muscles and promote oxygen-and nutrient-rich blood flow to the afflected area (level of evidence : 1A).[49]

→ Thermotherapy might be useful for reduction of pain during excercises.

● ‘Low level laser therapy’ is found to be an effective method for treating heel spurs. Although, more research with larger groups is needed for more evidence. (Level of Evidence: 4)[50]

● Conventional therapy includes ultrasound, Laser, passive and active stretching and strengthening of the muscles of the legs and cold and warmth applications (Contrast Bath). The aim is to eliminate the inflammation surrounding the spur. This kind of treatment may take 6 to 12 months.

● Conservative treatment:

While conservative treatments can help reduce the symptoms of bone spurs, they do not always treat the source of your pain.

● radial shockwave therapy consists of very high-energy mechanical waves, pointed at the Fasciitis plantaris. By the growth of blood vessels the inflammation shall be taken away.(D'andrea greve et al., 2009, B)

● Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy:

However there are different studies who claim ESWT is not effective in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. (Buchanan et al. 2002, A2; Haake et al. 2003, A2) Because of this discrepancy between studies, further support for an effective treatment with ESWT is needed, because there was a remarkable positive effect of ESWT pointed at the calcaneal spur, but the difference between the presence and absence of a calcaneal spur was not significant enough (level of evidence: 1A).[51] According to De Vera Barredo et al.(2007, A1) night splints, massage, taping, acupuncture, walking casts, laser therapy and cryotherapy are more means to help the patient.

- “ESWT appeared effective in relieving heel pain among patients with calcaneal spur especially when given within the first 4 months after the start of patient complaint. ECSWT is recommended to be the first choice in treating calcaneal spur.” (level of evidence: 2A) [52]

- “ESWT should be useful when the treatment is given with an amount of at least 3x500 impulses.” (level of evidence: 1B) [53]

- “ESWT in addition to stretching exercises, heel cups, NSAID, and corticosteroid injections, was given to patients with heel pain and radiologically diagnosed heel spurs. This study aimed to investigate the effects of ESWT on calcaneal bone spurs and the correlation between clinical outcomes and radiologic changes. After five ESWT treatments, no patients had significant spur reductions, but 19 patients (17.6%) had a decrease in the angle of the spur, 23 patients (21.3%) had a decrease in the dimensions of the spur, and one patient had a broken spur. The therapy produces significant effects in reducing patients’ complaints about heel spurs but is maybe not the best therapy for heel spurs. Therefore further studies are required about the effectiveness of ESWT.”(level of evidence: 2C) [54]

Orthotics[edit | edit source]

The effect of orthotics can only be reached when the calcaneal spur is related to plantar fasciitis!

1) Night Splints

“A conservative treatment in combination with the use of a night splint that keeps the ankle in 5-degree of dorsiflexion for eight weeks; Patients without previous treatments for plantar fasciitisobtain significant relief of heel pain in the short term with the use of a nightsplint incorporated into conservative methods; however, this application does not have a significant effect on prevention of recurrences after a two-year follow-up.” (level of evidence: 4)

or Heel spur pads should relieve heel spur pressure and inflammation and catch shock forces and distribute them evenly throughout the heel reducing stress. However: “Heel spur pads were ineffective in reducing rearfoot pressure and increased rearfoot peak forces while orthotics and customised orthotics reduced rearfoot peak forces on both sides. Pre-fabricated and customised orthotics are therefore useful in distributing pressure uniformly over the rearfoot region.” (level of evidence: 3A) [55]

3) Foot wear Modification

- Footlogics: provides relief from Plantar Fasciitis (heel pain & heel spurs), Achilles Tendonitis and also ball of foot pain. Corrects over-pronation, fallen arches & flat feet.

- Insoles: “Patients with heel pain, diagnosed as Sever's injury, wore insoles with no other treatments added and all patients maintained their high level of physical activity throughout the study period. Significant pain reduction during physical activity when using insoles was found. (level of evidence: 1B) [56]

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Websites:

Buzzle.com, Intelligent Life on the web. Calcaneal spur. http://www.buzzle.com/articles/calcaneal-spur.html (accessed 15 november 2010)

MedicineNet.com. Definition of calcaneal spur. http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=7095 (accessed 15 november 2010)

Books:

Brukner & Khan’s, Clinical sports medicine, 4th edition, p.844-851

Dr. Mark E. Wolpa, The sports medicine guide – treating and preventing common athletic injuries, p.51- 54

Paul M. Taylor & Diane K. Taylor, conquering athletic injuries, p.77-78

David C. Reid, Sports injury assessment and rehabilitation, p.195- 200

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Lateral plantar nerve release with or without calcaneal drilling for resistant plantar fasciitis. [57] (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26321559?dopt=Abstract)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Johal KS .,‘Plantar fasciitis and the calcaneal spur: Fact or fiction?’., Foot Ankle Surg.,18 March 2012 (level of evidence 3B)

- ↑ Gill LH. Plantar fasciitis: diagnosis and conservative management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 1997

- ↑ McCarthy DJ, Gorecki GE: The anatomical basis of inferior calcaneal lesions. J Am Podiatry Assoc 69527-536,1979 (level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ Young CC, Rutherford DS, Niedfeldt MW. Treatment of plantar fasciitis. AmfckLRFam Physician 2001 (level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Heyd, Reinhard, et al. "Radiation therapy for painful heel spurs." Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 183.1 (2007): 3-9. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ McCarthy DJ, Gorecki GE: The anatomical basis of inferior calcaneal lesions. J Am Podiatry Assoc 69527-536,1979 (level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ E.K. Agyekum., “Heel pain: A systematic review”., Chinese Journal of Traumatology., 2015 (level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ B. Jasiak-Tyrkalska., ‘Efficacy of two different physiotherapeutic preocedures in comprehensive therapy of plantar calcaneal spur’., Fizjoterapia Polska., January 2007 (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Zhou, Binghua, et al. "Classification of Calcaneal Spurs and Their Relationship With Plantar Fasciitis." The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 54.4 (2015): 594-600. (level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Henri L. Duvries., “Heel Spur (Calcaneal Spur)”., AMA Arch Surg., (level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Chauveaux, D., et al. "A new radiologic measurement for the diagnosis of Haglund's deformity." Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 13.1 (1991): 39-44. (level of evidence: I)

- ↑ Perhamre, Stefan, et al. "Sever’s injury: a clinical diagnosis." Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 103.5 (2013): 361-368. (level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Hosgoren, B., A. Koktener, and Gülçin Dilmen. "Ultrasonography of the calcaneus in Sever's disease." Indian pediatrics 42.8 (2005): 801. (level of evidence: 4)

- ↑ Yu, Sarah M., and Joseph S. Yu. "Calcaneal avulsion fractures: an often forgotten diagnosis." American Journal of Roentgenology 205.5 (2015): 1061-1067. (level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Andrew J., John A. DiPreta, and David Misener. "Plantar heel pain." Medical Clinics of North America 98.2 (2014): 339-352. (level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Aldridge, Tracy. "Diagnosing heel pain in adults." American family physician 70 (2004): 332-342. (Level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Donley BG, Moore T, Sferra J, Gozdanovic J, Smith R. The efficacy of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID) in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled study. Foot Ankle Int 28:20–23, 2007.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Kalaci A, Cakici H, Hapa O, Yanat AN, Dogramaci Y, Sevinç TT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis using four different local injection modalities: a randomized prospective clinical trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 99:108–113, 2009.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Kiter E, Celikbas E, Akkaya S, Demirkan F, Kilic BA. Comparison of injection modalities in the treatment of plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 96:293–296, 2006. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Buccilli TA Jr, Hall HR, Solmen JD. Sterile abscess formation following a cortico- steroid injection for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 44:466– 468, 2005. (level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Porter MD, Shadbolt B. Intralesional corticosteroid injection versus extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciopathy. Clin J Sport Med 15:119–124, 2005. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Placzek R, Holscher A, Deuretzbacher G, Meiss L, Perka C. [Treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with botulinum toxin Adan open pilot study on 25 patients with a 14-week-follow-up.]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 144:405–409, 2006. German. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Placzek R, Deuretzbacher G, Meiss AL. Treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with Botulinum toxin A: preliminary clinical results. Clin J Pain 22:190–192, 2006. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Babcock MS, Foster L, Pasquina P, Jabbari B. Treatment of pain attributed to plantar fasciitis with botulinum toxin a: a short-term, randomized, placebo- controlled, double-blind study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 84:649–654, 2005. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Urovitz EP, Birk-Urovitz A, Birk-Urovitz E. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain. Can J Surg 51:281–283, 2008. (level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Fishco WD, Goecker RM, Schwartz RI. The instep plantar fasciotomy for chronic plantar fasciitis. A retrospective review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 90:66–69, 2000.(level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Woelffer KE, Figura MA, Sandberg NS, Snyder NS. Five-year follow-up results of instep plantar fasciotomy for chronic heel pain. J Foot Ankle Surg 39:218–223, 2000. (level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Shikoff MD, Figura MA, Postar SE. A retrospective study of 195 patients with heel pain. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 76:71–75, 1986. (level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Williams PL. The painful heel. Br J Hosp Med 38:562–563, 1987. (level of evidence: 4)

- ↑ Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 166:1305–1310, 2006.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Roos E, Engstrom M, Soderberg B. Foot orthoses for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int 27:606–611, 2006.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME, Moore EA, Murray JC, Wilding GE, Baumhauer JF. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A:1270–1277, 2003.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Digiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, Graci PA, Williams TT, Wilding GE, Baumhauer JF. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:1775–1781, 2006.(level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Pfeffer, Glenn, et al. "Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis." Foot &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Ankle International 20.4 (1999): 214-221.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Lee, Sae Yong, Patrick McKeon, and Jay Hertel. "Does the use of orthoses improve self-reported pain and function measures in patients with plantar fasciitis? A meta-analysis." Physical Therapy in Sport 10.1 (2009): 12-18.(level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Cleland JA, Abbott JH, Kidd MO, Stockwell S, Cheney S, Gerrard DF, Flynn TW. Manual physical therapy and exercise versus electrophysical agents and exercise in the management of plantar heel pain: a multicenter randomized clinical trial.(level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician 72:2237–2242, 2005. (level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Lee, Gregory P., John A. Ogden, and G. Lee Cross. "Effect of extracorporeal shock waves on calcaneal bone spurs." Foot &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; ankle international 24.12 (2003): 927-930. (level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Marks W, Jackiewicz A, Witkowski Z, Kot J, Deja W, Lasek J. Extracorporeal shock- wave therapy (ESWT) with a new-generation pneumatic device in the treatment of heel pain. A double blind randomised controlled trial. Acta Orthop Belg 74:98– 101, 2008. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Chuckpaiwong B, Berkson EM, Theodore GH. Extracorporeal shock wave for chronic proximal plantar fasciitis: 225 patients with results and outcome predictors. J Foot Ankle Surg 48:148–155, 2009. (level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Pribut SM. Current approaches to the management of plantar heel pain syndrome, including the role of injectable corticosteroids. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 97:68–74, 2007. (Level of Evidence: 5)

- ↑ Weil L Jr, Glover JP, Sr Weil LS. A new minimally invasive technique for treating plantar fasciosis using bipolar radiofrequency: a prospective analysis. Foot Ankle Spec 1:13–18, 2008. (Level of Evidence: 4)

- ↑ Lucas, Douglas E., Scott R. Ekroth, and Christopher F. Hyer. "Intermediate-Term Results of Partial Plantar Fascia Release With Microtenotomy Using Bipolar Radiofrequency Microtenotomy." The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery54.2 (2015): 179-182.(level of evidence: 3B)

- ↑ Chou, Andrew Chia Chen, et al. "Radiofrequency microtenotomy is as effective as plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis." Foot and Ankle Surgery (2015). (Level of Evidence: 4)

- ↑ Cinar, E., F. Uygur, and S. Toprak Celenay. "AB1447-HPR The efficacy of low level laser therapy in the treatment of calcaneal spur." Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 71.Suppl 3 (2013): 757-757. (Level of Evidence: 4)

- ↑ Hautmann, M. G., U. Neumaier, and O. Kölbl. "Re-irradiation for painful heel spur syndrome." Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 190.3 (2014): 298-303. (level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Holtmann, Henrik et al. “Randomized Multicenter Follow-up Trial on the Effect of Radiotherapy for Plantar Fasciitis (painful Heels Spur) Depending on Dose and Fractionation – a Study Protocol.” Radiation Oncology (London, England) 10 (2015): 23. PMC. Web. 8 Jan. 2016. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Costantino, C., et al. "Cryoultrasound therapy in the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with heel spurs. A randomized controlled clinical study." European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine 50.1 (2014): 39-47. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ E.K. Agyekum., “Heel pain: A systematic review”., Chinese Journal of Traumatology., 2015 (level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Cinar, E., F. Uygur, and S. Toprak Celenay. "AB1447-HPR The efficacy of low level laser therapy in the treatment of calcaneal spur." Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 71.Suppl 3 (2013): 757-757. (Level of Evidence: 4)

- ↑ Lee, Gregory P., John A. Ogden, and G. Lee Cross. "Effect of extracorporeal shock waves on calcaneal bone spurs." Foot &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; ankle international 24.12 (2003): 927-930. (level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ .Tarek Shafshak ., “The Efficacy of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy in Calcaneal Spur”., American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation., 2014 (level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Krischek O., “Symptomatic low-energy shockwave therapy in heel pain and radiologically detected plantar heel spur”., Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb., April 1998 (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Yalcin E., “Effects of extracorporal shock wave therapy on symptomatic heel spurs: a correlation between clinical outcome and radiologic changes”., Rheumatol Int.; February 2012 (level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ Chia KK., “Comparative trial of the foot pressure patterns between corrective orthotics, formthotics, bone spur pads and flat insoles in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis”., Ann Acad Med Singapore., October 2009 (level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Perhamre S1., “Sever's injury: treatment with insoles provides effective pain relief”., Scand J Med Sci Sports., December 2011 (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Sadek, Ahmed Fathy, Ezzat Hassan Fouly, and Mostafa Mohammed Elian. "Lateral plantar nerve release with or without calcaneal drilling for resistant plantar fasciitis." Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 23.2 (2015): 237. (level of evidence: 1B)