Benign Positional Paroxysmal Vertigo (BPPV)

Original Editor - Lee Marshall, Lauren Russell, Brían Lillis, Anna Thommasen as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Chris Milne, Lee Marshall, Lauren Russell, Brían Lillis, Kim Jackson, Kai A. Sigel, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Admin, Anna Thommasen, Scott Buxton, 127.0.0.1, Ahmed M Diab, Melanie Reis, Karen Wilson, Candace Goh, Lucinda hampton, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Tony Lowe and Wendy Walker

Package Aims [edit | edit source]

The aim of this continuing professional development (CPD) package is to educate physiotherapists and increase awareness about Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) in an aging population. It introduces some of the current issues surrounding management of BPPV and aims to help reduce falls and unplanned hospital admissions by encouraging early diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

Not all aspects of BPPV are covered in-depth, but you are encouraged to use this package and its links as a guide to further your understanding of the condition and to guide future learning. A set of learning outcomes has been devised to help facilitate this process. At the end of this CPD package you should be able to:

• Describe BPPV and recognize the signs, symptoms, and pathophysiology related to this condition.

• Utilize an evidence-informed approach to diagnose and treat BPPV.

• Critique current management of BPPV and demonstrate how physiotherapists might contribute to diagnosis and treatment.

• Demonstrate the value of early diagnosis and treatment of BPPV in falls prevention and unplanned hospital admissions.

• Identify further learning needs associated with BPPV for practice.

• Critically reflect on your current and emerging role in diagnosis and treatment of BPPV.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Defining BPPV[edit | edit source]

BPPV is a peripheral vestibular disorder characterized by short episodes of mild to intense dizziness and influenced by specific changes in head position. BPPV is the most common cause of vertigo accounting for nearly one-half of patients with peripheral vestibular dysfunction. It is often self-limiting, but in some cases may become chronic and greatly affect an individual’s quality of life.[1]

Related Anatomy of the Ear[edit | edit source]

The inner ear is quite complex and includes both the organs for hearing (the cochlea) and balance (vestibular) (see Figure 1). The vestibular section of the ear consists of the saccule, utricle and three semicircular canals (anterior, posterior and horizontal). Each of these canals plays an essential role in maintaining balance.[2]The semicircular canals are responsible for detecting rotational movement of the head. They are situated at right angles to one another and contain fluid called endolymph. Inertial changes with rotation of the head cause this endolymphatic fluid to shift. The fluid shift lags behind movement of the head and as a result pressure is exerted on the cupula, the motion sensory receptor at the base of the canal. Information regarding movement is then transduced and sent to the brain for interpretation.[2]

The saccule and utricle play a role in detecting linear acceleration along with gravity. The macula of the utricle is considered the structure at fault for BPPV. It contains otoconia (calcium carbonate particles) which are surrounded by a gelatinous matrix and stereociliary hairs (see Figure 2). These calcium particles behave similarly to endolymph, reacting to changes in gravity and acceleration.[2]

For more in-depth information regarding ear anatomy please click the link: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1948907-overview#aw2aab6b3

Pathophysiology of BPPV[edit | edit source]

BPPV occurs when the otoconia of the macula are dislodged and transferred into the lumen of one of the semicircular canals. This unintentional movement interferes with the endolymphatic system and stimulates the motion receptor (ampulla) of the affected canal, resulting in vertigo.[2]

Following this phenomenon, nystagmus ensues as a result of either canalithiasis or cupulolithiasis. Canalithiasis refers to freely moving otoconia settling within the posterior semicircular canal, causing the canal to be gravitationally sensitive. This is thought to result in posterior canal BPPV, the most common form of the condition. In about 5% of cases cupulolithiasis occurs, where the otoconia adhere to the cupula of the lateral semicircular canal causing it to be heavier than the surrounding endolymph. This is thought to result in lateral canal BPPV. The direction of nystagmus is different depending on location of the calcium carbonate crystals. Nystagmus pattern is provoked by ampullary nerve excitation in the affected canal, which is directly connected to extraocular muscles of the eye.[2]

The exact reason for the calcium crystals separating from the macula is not well understood. The condition is believed to arise following viral infection or trauma, but in the majority of cases it occurs in the absence of any identifiable illness or upset. It is also believed to be linked to age-related changes in the protein and gelatinous matrix of the otolithic membrane.[2]

Further information regarding the history and pathophysiology of BPPV can be found in this journal article: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijol/2011/835671/

Epidemiology of BPPV[edit | edit source]

BPPV is an idiopathic condition with approximately 50-70% of cases occurring without any known cause. It is most prevalent in people between the ages of 50 and 70 years old, though it can occur at any time.[1] The prevalence of BPPV has been reported to range from 10.7 to 64 per 100,000[3] and is the cause of at least 50% of reported cases of dizziness in the elderly population.[4].

In individuals under the age of 50 years BPPV most commonly occurs following head trauma. It is believed that the otoconia become dislodged due to concussive forces on the vestibular system. BPPV is also associated with viruses of the ear, ototoxicity, and migraines.[5] A European study, estimating the prevalence and incidence of BPPV in the general adult population showed a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%.[6] Furthermore, the study found females were more likely to be affected than males, with a lifetime prevalence of 3.2% versus 1.6%, respectively.

Relevance to Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that 9% of elderly patients receiving comprehensive geriatric assessment for non-balance-related health issues, have unrecognized BPPV.[7] These individuals experience higher incidences of falls, impairments of daily living, and depression.[7] Furthermore, falls in the elderly can result in secondary injury and may lead to unplanned nursing home and hospital admissions. Persistent untreated or undiagnosed vertigo in the elderly can lead to increased caregiver burden and resultant societal costs. Physiotherapy methods of diagnosis and treatment are safe, simple to administer, cost-effective, and encouraged to help relieve this burden.

The high percentage of undiagnosed patients is testament to the lack of knowledge surrounding BPPV. We believe it is crucial to educate and inform health care workers, namely physiotherapists, regarding this condition in order to reduce the amount of undiagnosed cases. Through this, we aim to reduce the number of unplanned hospital admissions and falls amongst the elderly population.

The Signs & Symptoms[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of BPPV are often transient, with symptoms commonly lasting less than one minute (paroxysmal).[8] Episodes of BPPV can resolve after a few weeks or months, but may reappear at a later time. Signs and symptoms may include:[8]

• Dizziness

• Vertigo (a sense that your surroundings are spinning or moving)

• Lightheadedness

• Loss of balance

• Blurred vision and nystagmus associated with vertigo

• Nausea

• Vomiting

Activities that bring about the signs and symptoms of BPPV can vary from person to person, but are almost always brought on by a change in the position of the head. These positional changes may include:

• Moving the head to one side

- example: when turning in bed

• Tilting the head backwards to look up

– example: hanging up washing or taking something from the top shelf

• Bending over

– example: to tie shoe laces

The typical features of a patient presenting with BPPV include:

• > 40 years of age

• Vertigo and dizziness lasting one minute or less

• One or more of the signs/symptoms listed above

• Onset of symptoms during activities which involve a change in the position of the head

• Limitations or modification of movements, to avoid provoking symptoms

• History of falls resulting from symptomatic episodes

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Principles of Clinical Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

BPPV can easily be diagnosed and treated through simple clinic-based procedures.[9] In the past, a wide variety of different tests and procedures have been explored for diagnosis of BPPV, but many of these techniques have been discredited in recent years. Currently the primary method of diagnosis involves in-depth subjective screening, followed by physical investigations and diagnostic manoeuvres to confirm BPPV. These methods of diagnosis have been shown to be clinically appropriate, simple to perform, and cost effective.[10] Early diagnosis of BPPV is important and may help improve quality of life for patients and reduce the risk of more serious injury. Techniques may be easily incorporated into routine physiotherapy assessment and should be considered for any patients presenting with symptoms of dizziness and vertigo.

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

The subjective assessment is the first step in clinically diagnosing BPPV. Any complaints of dizziness necessitate the taking of a detailed patient history and further investigation of the symptoms.[11] Patient history alone is insufficient to accurately diagnose BPPV, but patient description of vertigo can give a very good indication of the cause.[10] Clinicians should look out for patients describing sudden severe attacks of vertigo or dizziness, precipitated by head position and movement.[1] The most common movements thought to provoke symptoms are rolling over in bed, extension of the neck to look up, and bending forward.[1] Patients typically describe their vertigo as a rotational or spinning sensation provoked by these movements.[10]

Different studies have aimed to identify and validate useful questions when suspecting a diagnosis of BPPV. There are however no current guidelines for appropriate BPPV screening questions. Some important aspects of the condition have been identified which should be explored to rule out other causes. Clinicians should be asking patients questions regarding:

1. Type of dizziness and vertigo

2. Duration of dizziness and vertigo

3. Precipitating and exacerbating factors

4. Accompanying symptoms

These criteria can help rule out other conditions and support a diagnosis of BPPV.[11] Noda et al.[12] found that the trigger and duration of vertigo were particularly important in diagnosing BPPV. They highly suggest asking patients questions to explore whether they experience onset of dizziness when turning over in bed and dizziness for less than 15 seconds.[12] Answering yes to either of these questions indicates a potential diagnosis of BPPV. In addition to this, practitioners should ensure that rotatory vertigo, or a spinning sensation, is being experienced and distinguish this from light-headedness, which is dizziness without the sensation of movement.[11]

Once the subjective assessment is complete, the health care professional should have a good idea whether further investigation is needed. As mentioned, patient history and subjective examination is insufficient to accurately diagnose BPPV on its own, but should be sufficient to rule out other causes of dizziness and develop a working hypothesis to guide the physical examination.

Physical Assessment[edit | edit source]

If details of the subjective assessment and patient history indicate BPPV, then further physical investigation is needed to confirm a diagnosis. Physical diagnosis maneuvers involve a series of movements which aim to provoke nystagmus and symptoms of vertigo. The two diagnostic maneuvers used clinically are the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and the Supine Roll Test. A positive result on either of these tests indicates a diagnosis of BPPV. They also help to distinguish the type of BPPV and identify the ear involved.

Dix-Hallpike Maneuver[edit | edit source]

Evidence-based guidelines state that clinicians should diagnose posterior canal BPPV when vertigo and associated nystagmus is provoked by the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. [10] This test is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV.[10] As posterior canal BPPV is the most common type of BPPV, occurring in up to 90% of cases, this is the first maneuver which should be performed during the physical examination.[9] The clinician should look for provocation of nystagmus and make note of the direction and pattern of eye movements, as this will give an indication of the ear at fault. Nystagmus may fatigue and reduce with repetition of the maneuver, so looking out for this symptom is important to minimize the need for repeat testing.[10] Continued communication with the patient is essential to help establish and monitor when uncomfortable symptoms of vertigo arise.

Performing the Dix-Hallpike Maneuver[edit | edit source]

Prior to initiation of the maneuver clinicians should explain the basic features of the test and warn patients that it may provoke sudden onset of vertigo. After informed consent has been given, the patient is positioned in supine so that the head can hang, with support, off the posterior edge of the examination table by 20°.[10] The examiner should be in a position so that they are able to take the patient through the maneuver safely and effectively without losing support of the head. Bhattacharyya et al.[10] give a good description of the maneuver and break the procedure down into a series of five steps (see Figure 3):

Step 1) To begin the maneuver the patient should be seated on a table or plinth in an upright position, with the examiner to one side.

Step 2) The examiner rotates the patient’s head 45° to one side and positions their own body so that rotation may be maintained through the next portion of the maneuver. If the right side is to be tested then the head begins rotated 45° to the right. If the left side is being tested the head begins rotated 45° to the left.

Step 3) With the head fully supported and maintained at 45° of rotation, the examiner quickly moves the patient from the seated position to a supine position with the patient’s neck extended 20° off the edge of the examination table. The patient’s eyes should be visible and examined for nystagmus, making note of the latency, duration and direction of movement. The patient should also be questioned regarding symptoms of vertigo.

Step 4) After resolution of vertigo and nystagmus, the patient is slowly returned to the upright position. Patients may experience a reversal of the nystagmus when returning to this position and symptoms should be allowed to resolve before moving on.

Step 5) The entire maneuver should then be repeated with the head rotated to the opposite side.

A video demonstration of the Dix-Hallpike Maneuver and associated nystagmus

A positive Dix-Hallpike maneuver will elicit a typical pattern of nystagmus described as a mix of torsional and vertical movement, with the upper pole of the eye beating toward the downward facing affected ear.[9] If one ear is affected, nystagmus will be provoked when the affected ear is positioned downwards and not upwards. If both ears are affected nystagmus is elicited in both directions. A summary table of possible nystagmus characteristics has been provided.

Diagnostic Strength of Dix-Hallpike Maneuver[edit | edit source]

As mentioned, the Dix-Hallipike maneuver is considered the gold standard test for the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV and as such is one of the most common tests used for diagnosis.[10] As the current gold standard, few tests have explored the sensitivity and specificity of this maneuver, but studies have reported sensitivity up to 82% and specificity of 71% amongst experienced clinicians.[14] It is proposed to have a positive predictive value of 83% and a negative predictive value of 52%.[15] Due to the lower negative predictive value, a negative result cannot entirely rule out a diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV. If BPPV is still suspected, the test may need to be repeated on subsequent visits to confirm a negative or positive diagnosis.[10]

Supine Roll Test[edit | edit source]

If the Dix-Hallpike maneuver is negative, the patient should be tested for lateral (also referred to as horizontal) canal BPPV using the supine roll test. Lateral canal BPPV is the second most common type of BPPV with incidences of 10% to 15%.[10] The supine roll test is the preferred maneuver to diagnose lateral canal BPPV, though it is not as well-established as the Dix-Hallpike maneuver.[9] Again, the clinician should look for provocation of nystagmus and make note of the direction and pattern of eye movements. Prior to initiation of the maneuver, clinicians should explain the basic features of the test and warn patients that it may provoke sudden onset of vertigo. A positive test is indicated by the presence of vertigo and elicitation of nystagmus. The procedure may be broken down into some simple steps (see Figure 4):

Step 1) The patient is initially positioned in supine with the head in a neutral position over the edge of the table.

Step 2) With support from the clinician, the head is quickly rotated 90° to one side with the clinician observing the eyes for nystagmus.

Step 3) After any elicited nystagmus has resided, the head is returned to neutral and the eyes are once again observed for nystagmus.

A positive supine roll test will evoke two different patterns of nystagmus, which reflect the two different types of lateral canal BPPV. The two types of lateral canal BPPV are Geotropic and Apogeotropic. The pattern of nystagmus may also be described as geotropic or apogeotropic. Geotropic nystagmus refers to a nystagmus pattern where the upper half of the eye is directed towards the ground. Apogeotropic nystagmus refers to the opposite movement. The typical pattern of nystagmus seen for each type of BPPV is presented in the table below.

Patterns of Nystagmus[edit | edit source]

Table 1. was adapted from Balasouras et al.[9] and provides a basic summary of the different patterns of nystagmus which can be elicited by the two diagnostic maneuvers discussed. For additional information on the characteristic patterns of nystamus provoked in patients with BPPV, the reader is directed to Balasouras et al.[9], Parnes et al.[1], and Bhattacharyya et al.[10].

Imaging and Additional Investigations[edit | edit source]

Imaging and additional testing is generally not required or recommended for confirming diagnosis of BPPV, unless additional neurological symptoms exist or the patient has additional symptoms which warrant further exploration.[9][10][16] Imaging is not deemed to be useful in regular diagnosis of BPPV as the pathology occurring within the semicircular canals of the ear is beyond the resolution of current neuroimaging techniques.[10]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Treatment Techniques for BPPV[edit | edit source]

Management of BPPV has changed drastically over the past 20 years. Traditionally, treatment included advice on avoiding movements that induced vertigo and patients were prescribed medications for symptomatic relief.[1] Currently a shift has occurred towards treatment involving manual therapy and self-management techniques taught by qualified professionals. While spontaneous resolution of BPPV is possible, manual techniques are effective, easy to administer, and should be considered the first line of treatment.[17]

The correct treatment technique will depend on which side and semicircular canal has been affected.[18] Both the Modified Epley’s Maneuver and the Semont Liberatory Maneuver have been found to be beneficial in reducing symptoms of BPPV resulting from pathology of the posterior semicircular canal. Lateral canal positioning techniques have been shown to improve symptoms arising from pathology of the lateral semicircular canal.[1]

Treatment Techniques for Posterior Canal BPPV[edit | edit source]

Modified Epley's Maneuver [edit | edit source]

In 1992, Epley[19] first described the Canalith Repositioning Procedure (CRP) and demonstrated that 100% of the patients’ symptoms were relieved with this technique. Originally, Epley’s maneuver included sedation and mechanical skull vibrations.[1] A modified Epley’s maneuver, or Particle Repositioning Maneuver (PRM), has since been created that does not involve skull vibrations or sedation. It is show to be equally beneficial and easier to administer than the original technique.[1] Epley’s maneuver is designed to utilize gravity to move debris through the posterior semicircular canal into the utricle, resulting in decreased symptoms of BPPV.[20] It has been found to be well tolerated by patients and has a high success rate.[21] Epley’s maneuver involves the following steps (see Figure 5):

Step 1) Place the patient in a sitting position

Step 2) Rotate the patient’s head 45° towards the effected ear

of neck extension where the affected ear is pointed towards the ground

Step 3) Hold the position for 30 seconds

Step 4) Turn the head 90° so that the unaffected ear faces the ground, ensuring that 30° of neck extension is maintained

Step 5) Hold the position for 30 seconds

Step 6) Keeping the head and neck in this position relative to the body, the patient rolls onto their shoulder that the head is facing (resulting in the rotation of the head another 90o and the patient should be looking downwards at a 45° angle

Step 7) Hold the position for 30 seconds

Step 8) Bring the patient to an upright posture while maintaining the 45° rotation of the head

Step 9) Have the patient sit for 30 seconds.[22]

A video demonstration of the Modified Epley’s Maneuver

Following the maneuver, the patient should be advised:

• To keep their head upright- Don’t pitch their head up or down

• Not to lie supine for 48 hours

• Not to lie on the affected side for 1 week

• Avoid bending over for 1 week (if possible)

• They may feel a sensation of light-headedness and may be slightly off balance for a few days following the treatment.[24]

Following treatment, the patient may be taught to perform this maneuver on their own as a complimentary therapy.[25] This can be especially beneficial for patients who do not respond to a single treatment, or those with frequent recurrence.[25] Recurrence rates have been estimated at 50% within the first 4-5 years after initial treatment. An accurate history is important to determine if the patient is at high risk of reoccurrence.[26]

When self-administered, Epley’s maneuver has been found to be more effective than the self-administered Semont Liberatory maneuver. It has been shown to be most beneficial when performed as an adjunct treatment to Epley’s maneuver administered clinically by a health care practitioner.[21]

Semont Liberatory Maneuver [edit | edit source]

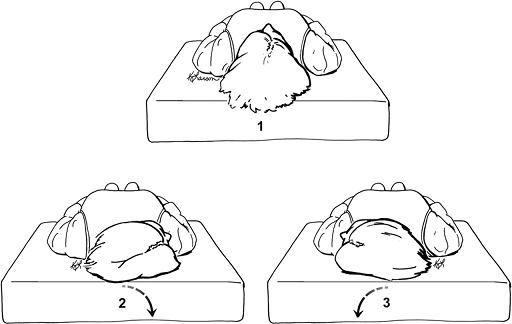

First described in 1988, the Semont liberatory maneuver aims to move particles through the posterior semicircular canal and into the utricle, much like Epley’s maneuver.[1] The Semont liberatory maneuver may be summarized in the following steps (see Figure 6):

Step 1) Place the patient in a sitting position with the head turned away from the affected side

Step 2) Quickly and passively bring the patient backwards to a position of side lying (on the affected side) with the head turned upward

Step 3) Hold the position for 5 minutes

Step 4) Quickly and passively bring the patient back to the sitting position and then to side lying on the opposite side with the head turned downward

Step 5) Hold this position for 5 minutes

Step 6) Bring the patient to an upright posture.

A video demonstration of the Semont Liberatory Maneuver

While the Semont liberatory maneuver has been shown to be effective, the quality of the research is poorer than that for the Epley’s maneuver.[21] For this reason, Epley’s maneuver should be the main technique used in the treatment of BPPV. The Semont liberatory maneuver may be attempted if symptoms persist after administration of Epley’s maneuver.

Treatment Techniques for Lateral Canal BPPV[edit | edit source]

While less common, lateral BPPV can be caused by particles within the lateral semicircular canal. A correct diagnosis of lateral BPPV is important as a posterior canal repositioning maneuver will be ineffective for this type of BPPV.[1]

Prolonged Position Maneuver[edit | edit source]

The prolonged position maneuver can be used for lateral BPPV and involves the patient lying on their side with the affected ear up for 12 hours. It has been shown that this maneuver is effective and resolves symptoms in 90% of patients after the first attempt.[1] It is worth noting that with this maneuver there is a risk that some patients will experience movement of particles into the posterior canal, resulting in posterior BPPV.[1] If movement into the posterior canal occurs, the Epley’s maneuver can be applied to resolve symptoms.

Barrel Roll[edit | edit source]

Another option for treatment of lateral canal BPPV is termed the “barrel roll”. In this maneuver the patient is rolled 360°, beginning and ending in the supine position, while maintaining the lateral semicircular canal perpendicular to the ground.[1] During this treatment technique, the patient is rolled away from the affected ear in 90° increments until a full roll is achieved.[1]

The evidence for both of these treatment techniques is of low quality and further research is needed. Based on the current evidence, the rate of effectiveness for these treatment techniques is approximately 75%.[10]

Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises[edit | edit source]

Vestibular rehabilitation exercises are commonly included in the treatment of BPPV and are designed to train the brain to use alternative visual and proprioceptive cues to maintain balance and gait.[18] It has been shown that these exercises improved nystagmus, postural control, movement-provoked dizziness, the ability to perform activities of daily living independently, and levels of distress.[18] While no single vestibular rehabilitation exercise has been shown to reduce the symptoms of BPPV, a program of therapies that can include self-administered repositioning maneuvers, gaze stabilization exercises, falls prevention training, and patient education may be beneficial in reducing the symptoms of BPPV and improve quality of life.[10]

The evidence supporting the efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation exercises in reducing symptoms of BPPV is lacking.[10] Steenerson et al.[28], found that Epley’s maneuver administered by a health care practitioner was a better treatment technique than vestibular rehabilitation exercises. Vestibular exercises were, however deemed to be better than no treatment at all. No single form of vestibular rehabilitation exercise has been found to be superior and exercises appear to have a greater effect when performed together, rather than as single exercises alone.[10]

Cawthorne-Cooksey Exercises[edit | edit source]

The Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises aim to relax the neck and shoulder muscles, train eyes to move independently of the head, and to practice balance and head movements that cause dizziness.[29] The exercises consist of a series of eye, head, and body movements, in increasing difficulty, which aim to provoke symptoms.[10] The goal of these exercises is to fatigue the vestibular response and force the central nervous system to compensate by habituation to the stimulus.[10]

A video description of the Cawthorne-Cooksey Exercises

Brandt-Daroff Exercises[edit | edit source]

The Brandt-Daroff exercises are a series of particle repositioning exercises that can be performed without a qualified health professional present and are easily taught to the patient.[29] While beneficial, these exercises are more time consuming than other forms of treatment. They are completed by the patient in bed, 3 sets a day for 2 weeks and aim to help reduce the chance of reoccurrence of BPPV and promote the loosening of canaliths.[10] Radke et al.[31] found that when these exercises are performed as the only form of treatment, they were successful at relieving the symptoms of BPPV in only 25% of individuals after one week of administration. The Brandt-Daroff exercises have been found to be a beneficial adjunct treatment in the symptomatic relief of BPPV.[10]

The Brandt-Daroff exercises may be summarized in the following steps (see Figure 7):

Step 1) Have the patient sit on the edge of the bed and turn their head 45° to one side

Step 2) Quickly have the patient lie down on the opposite side that their head is facing

Step 3) Have the patient hold this position for 30 seconds

Step 4) Return to the sitting position

Step 5) Repeat steps 1-4 while facing the opposite direction, alternating until 6 repetitions have been completed.[29]

A video demonstration of the Brandt-Daroff Exercises

Medication[edit | edit source]

Previously, vestibular suppressants have been prescribed to treat BPPV. These medications are shown to have little effect; with any positive result occurring over a similar timescale to that of a control, suggesting spontaneous resolution of the vertigo.[10] Due to the mechanical nature of BPPV and its association with very brief episodes of vertigo, BPPV management via drugs is essentially ineffective.[2]

Implications in Falls and Unplanned Hospital Admissions [edit | edit source]

Falls: What's the Problem?[edit | edit source]

Dizziness is one of the most common symptoms described by elderly people and can be associated with balance disorders, reduced quality of life, functional decline and falls.[33][34] The incidence of falls is a huge problem when considered alongside the shifting demographics in the UK.[35] There are large financial implications for the NHS in relation to hospitalization following falls and the cost of treating resultant injuries. The UK population is ageing and therefore the cost of falls incurred by the NHS and other agencies is expected to escalate.[35]

Here are some facts and figures which relate to falls:

- In 2007 there were over 1 million falls[36]

- One in 3 people over 65 have a fall every year[36]

- Every 5 hours in the UK, an elderly person dies after a fall at home[36]

- Based on current trends in the UK, hip fractures among older people resulting from a fall may rise to 120,000 per annum by 2015[36]

To put these figures into context, in relation to falls, in the UK:

- One hip fracture every 9 mins; each with an estimated cost of £12,000-18,000[37]

- One wrist fracture every 10 mins; each with an estimated cost of £450[37]

- 500 people admitted to hospital every day[37]

Falling has been reported as the primary reason for an elderly patient to be admitted to accident and emergency.[38] In addition, falling is the main mechanism for minor injury in the elderly population.[39]

Falling is not just a problem attributed to the UK; approximately 40% of the population over the age of 65 in the USA falls at least once a year, with 1 in 40 of them being admitted to hospital. Of those that are hospitalized, only around half will still be alive 12 months later.[40] Findorff et al.[41] stated that 20-30% of people who fall in the USA require medical support, the cost of which is estimated at $6-8 billion per year. For those over the age of 65, falls account for approximately 6% of medical expenditure for that age-group within the USA.[40] Based on the causes and circumstances of falls, it has been estimated that 2/3 of deaths caused by falls are in fact preventable.

These facts and figures clearly highlight the huge economic impact of falls on the NHS and financial obligation which accompanies treatment of associated injuries. It is imperative that illnesses/disorders which can make individuals more likely to suffer falls as a result of impaired balance are treated effectively. This will help to prevent unplanned hospital admissions which are both costly for the NHS and to the patients’ quality of life.

Impact of BPPV on Falls and Admissions[edit | edit source]

It has been well established that disorders within the vestibular system increases the risk of falling.[7] The presence of the vestibular dysfunction means that patients do not receive the correct information signals, making them unable to initiate the appropriate avoidance behaviour prior to impact, worsening the eventual outcome of the fall.[42] BPPV has been found to account for approximately 20% of all dizziness and is the most common vestibular disorder; BPPV is therefore hugely implicated in falls.[8]

BPPV and other vestibular disorders have been deemed the primary etiology in 13% of falls. In a study by Oghalai et al.[7] it was found that out of a random sample of an inner-city geriatric population, 9% were found to have previously undiagnosed BPPV. They also found that those with unrecognized BPPV were more likely to have reduced activities of daily living scores and to have sustained a fall in the past 3 months. Gananca et al.[43] carried out a study to determine the circumstances and consequences of falls in elderly people and found that 43.8% of the participants had BPPV diagnosis. Out of the 64 participants, over half (53.1%) had reported recurrent falls, with over 80% reporting a tendency to fall. This highlights vestibular disorders, within which BPPV appears to be most prevalent, as a major precursor of falls in the elderly.[43]

Research has shown that elderly patients suffering from BPPV suffer more falls than those not suffering from BPPV, increasing the likelihood of unplanned hospital admissions for secondary injuries such as fractures.[10] Based on a recent survey in the USA, people over the age of 40, who reported dizziness and vertigo, were 12 times more likely to have also reported a fall.[44] Marchetti et al.[39] found that patients who had suffered a hip fracture were also likely to suffer from a vestibular dysfunction.

Due to the increased prevalence of BPPV with age, patients suffering from this condition will often have medical comorbidities which need to be taken into consideration when diagnosing and treating BPPV. Patients with BPPV demonstrate higher rates of diabetes, stroke, hypertension and vision problems.[45] Patients with pre-existing conditions, especially stroke and peripheral neuropathy (as a result of diabetes), may already have existing balance, gait and proprioceptive problems. This predisposes these patients to a greater risk of falling during symptomatic periods and great care must be taken to minimize these risks and ensure effective treatment.[45] Patients who have osteoporosis are at greater risk of fractures from falls and therefore should be identified and monitored very closely with falls risk assessments.[36] When looked at from a different perspective, it would be useful to routinely screen patients who are identified as having a history of recurrent falls for BPPV. This would ensure BPPV is diagnosed in patients who are routinely falling as a result of the condition and allow them to get the appropriate treatment, aiming to prevent future falls and unplanned hospitals admissions.

Individuals with balance or vestibular disorders such as BPPV have a tendency to restrict their activity levels and social commitments, in an attempt to avoid the consequences of falling.[39] It has been found that those patients with a fear of falling also report psychological issues such as reduced confidence, anxiety, and depression.[36] This evidence highlights the effect that BPPV can have in diminishing the quality of life for sufferers.

What Role Do Physiotherapists Have?[edit | edit source]

Acquiring a good knowledge of the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment techniques involved in the management of BPPV allows for early diagnosis and effective intervention. It is necessary for us, as physiotherapists to recognize BPPV in the initial assessment; avoiding unnecessary clinical tests and hospital visits being required before BPPV is diagnosed.[34] As physiotherapists are often the first point of contact for these patients, it is vital that we have the skills to recognize BPPV. Once a diagnosis has been made, treatment can begin, this ensures that the patient recovers as quickly as possible, and minimizes the impact of BPPV on their life. In reality, diagnosis of BPPV is relatively straightforward when patient’s history and correct diagnostic tests are performed in the physical assessment.[17] The treatment of BPPV, as described in this learning package, is also simple to perform and is a cost and time effective method of management. The impact of falls and hospital admissions resulting from BPPV is costly both in terms of healthcare bills but also on patients’ physical health and quality of life. At present, BPPV is being undiagnosed too frequently, and is often only recognized upon admittance due to a secondary injury caused by a fall.[45] By physiotherapists having the appropriate knowledge and developing their skills in the diagnostic and treatment techniques, BPPV can be managed more effectively. Appropriate intervention by physiotherapists and other healthcare professionals can help to reduce the falls associated with BPPV and as a result prevent unplanned hospital admissions.

Due to the high recurrence rate of BPPV, it is recommended that patients are educated as to how to self-manage the condition so that if it does present itself again, the patient is able to treat themselves accordingly. A longitudinal study suggested that BPPV has a recurrence rate of between 40-50% in a 5 year follow up following treatment which was initially successful, therefore patients should be taught how to self-manage their condition, and therefore minimize the likelihood of readmission.[2] If a patient is not seen until after a fall, it is imperative to discover what led to the fall, possibly getting reports from other witnesses such as family members who may have a better recollection of the incident.[40] We, as physiotherapists have a huge role in falls prevention and need to be able to make an informed judgment for referral to falls prevention teams, especially if the patient has recurring BPPV. Post fall assessments have resulted in significantly fewer falls through the detection of risk factors and previously undetected conditions, thus reducing hospital admissions.

What Now? [edit | edit source]

An increased knowledge and awareness of BPPV will have a positive impact on the health of the elderly population and their quality of life. These changes are extremely relevant in the context of the UK’s shifting demographics and ever-aging population and as physiotherapists we have an important role to play. Now that you have a basic understanding of the anatomy, pathophysiology and current management of this condition, you are encouraged to reflect on you current role in BPPV management and consider how your own practice may be improved. You are encouraged to further your learning by completing the self-test questions in the next section of this package.

Self-Test[edit | edit source]

The following set of self-test questions has been developed to test your knowledge on BPPV and to encourage self-reflection on current practice. Many of the answers can be found within this CPD package, but the reader is encouraged to use links provided to explore additional resources available on this subject.

1) Explain in your own words what Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2) Describe the pathophysiology of BPPV and name the two most likely causes.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3) Describe the possible signs and symptoms of a patient presenting with BPPV.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

4) What are some typical movements/activities which may provoke symptoms of BPPV?

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5) Create a series of questions which may be useful to ask the patient when suspecting a diagnosis of BPPV.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

6) Utilizing the links provided in this package, determine any cautions and contraindications which may affect performance of the Dix-Hallpike Maneuver and Supine Roll Test.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

7) Briefly describe what you need to look for when performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and Supine Roll Test.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

8) Think about how you might describe the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and Supine Roll Test to the patient. What elements of these tests might be important for the patient to understand before administration?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

9) Using the links provided watch videos on the diagnostic and treatment techniques discussed in this package. If you are still unclear on the techniques ask a colleague or supervisor for advice and guidance.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

10) a. A patient is suffering from BPPV in the right posterior semicircular canal. Which of the two diagnostic tests would elicit a positive result? What characteristic symptoms would you expect to see upon completion of this test?

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

b. What treatment approach would you take and how might you modify the Epley’s maneuver to be used for treatment of this patient?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

11) a. A patient presents with left lateral canal BPPV. What characteristic symptoms would you expect to see? How would you go about treating this patient?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

b. What is the possible side effect of attempting a lateral canal repositioning technique? What can be done if this side effect occurs?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

12) Take a moment to reflect on your own practice. How do you usually asses and treat patients who present with episodes of dizziness? Are there any things you would change, based on this information in this package?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

13) Make a list of questions you still have regarding BPPV. Utilizing the links provided to see if you can answer these questions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

14) Discuss with a colleague the implications of early BPPV diagnosis and treatment in falls prevention and unplanned hospital admissions. Are there any things you can do as practitioners to influences these?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

For a printable PDF of the self-test questions please follow this link: BPPV CPD Self-Test Questions

Links[edit | edit source]

Defining BPPV and its Pathophysiology

- http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijol/2011/835671/

- http://www.neuroanatomy.wisc.edu/selflearn/BPPV.htm

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnostic Videos

- Dix-Hallpike Maneuver: http://www1.imperial.ac.uk/resources/6891997E-5A13-41E7-875B-5982A5F07A87/[46]

Treatment Links

- Epley’s Maneuver: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ZgUx9G0uEs[23]

- Semont Liberatory Maneuver: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A72UjulJSzE[27]

- Cawthorne-Cooksey Exercises:

- http://foi.avon.nhs.uk/Download.aspx?r=1&did=7775&f=CawthorneCookseyExercises-3.pdf

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXyg9n3nFQk[30]

- Brandt-Daroff Exercises: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTZfIv165sY[32]

Additional Videos

- Diagnosis and Treatment: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOJOArGmepM[47]

- Nystagmus Pattern for Right BPPV: http://www1.imperial.ac.uk/resources/B1C72EE9-92DC-41DC-B802-D3B779FE8873/[48]

Additional Links for BPPV

- NHS- Clinical Knowledge Summaries: http://www.cks.nhs.uk/benign_paroxysmal_positional_vertigo/management/scenario_diagnosis/diagnosis/hallpike_manoeuvre#471758006

- Patient.co.uk: http://www.patient.co.uk/health/Benign-Paroxysmal-Positional-Vertigo.htm

Read 4 Credit[edit | edit source]

|

Would you like to earn certification to prove your knowledge on this topic? All you need to do is pass the quiz relating to this page in the Physiopedia member area.

|

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Parnes L, Agrawal S, Atlas J. Diagnosis and Management of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) 2003; 169(7): 681-693.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Fife TD. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Seminars in neurology. 2009;29(5):500-508.

- ↑ Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2004: CD003162.

- ↑ Froehling DA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Beatty CW, Offord KP, Ballard DJ. Benign positional vertigo: incidence and prognosis in a population based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1991;66:596-601

- ↑ Ishiyama A, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW. Migraine and benign positional vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2000;109:377–380.

- ↑ Von Brevern M, Radtke, A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, Lempert T, Neuhauser H. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2007;78:710-715.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, Stewart MG, Jenkins HA. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2000;122(5):630-634.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Musat J. The Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Benign Paraoxysmal Positional Vertigo in the Elderly. Romanian Journal of Neurology 2010;9(4):189-192.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Balasouras DG, Koukoutsis G, Ganelis P, Korres GS, Kaberos A. Diagnosis of single- or multiple-canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo according the type of nystagmus. International Jounral of Otalaryngology. 2011; 1-13.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 10.19 10.20 10.21 10.22 10.23 Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2008;139(5):S47-S81.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Strupp M and Brandt T. Diagnosis and treatment of vertigo and dizziness. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008; 105(10): 173-180.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Noda K, Ikusaka M, Ohira Y, Takada T, Tsukamoto, T. Predictors for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with positive Dix-Hallpike test. International Journal of General Medicine. 2011; 4: 809–814.

- ↑ Dix Hallpike. [Video: Website]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8NxjG80V7OU . 2011. (Accessed October 30 2012).

- ↑ Lopez-Escamez J, Gamiz M, Fernandez-Perez A, Gomez-Fiñana M, Sanchez-Canet I. Impact of treatment on health-related quality of life in patients with posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otology & neurotology. 2003; 24(4): 637-641.

- ↑ Hanley K and O-Dowd T. Symptoms of vertigo in general practice a prospective study of diagnosis. British Journal of General practice. 2002; 52: 809-812.

- ↑ Alvarenga GA, Barbosa MA, Porto CC. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo without nystagmus: diagnosis and treatment. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngol. 2002; 77(6): 799-804.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Angeli SI, Hawley R, Gomez O. Systematic approach to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery 2003;128(5):719-725.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Swartz R, Longwell P. Treatment of Vertigo. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2005; 71: 1115-1122.

- ↑ Epley J. The Canalith Repositioning Procedure: For Treatment of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. American Academy of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. 1992; 107(3): 399-404.

- ↑ Epley J. Positional Vertigo Related to Semicircular Canalithiasis. American Academy of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. 1995; 112: 154-161.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Helminski J, Zee D, Janssen I, Hain T. Effectiveness of Particle Repositioning Maneuvers in the Treatment of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: A Systematic Review. Physical Therapy. 2010; 90: 663-678.

- ↑ Gans R, Harrington-Gans P. Treatment Efficacy of Benign aroxysmal ositional Vertigo (BPPV) with Canalith Repositioning Maneuver and Semont Liberatory Maneuver in 376 Patients. Vestibular Diagnosis and Rehabilitation Science and Clinical Application. 2002; 23(2): 129-142.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 How to do the Epley Maneuver. [Video: Website] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ZgUx9G0uEs. 2010 (Accessed October 23 2012)

- ↑ Kenny T. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. http://www.patient.co.uk/health/Benign-Paroxysmal-Positional-Vertigo.htm (Accessed October 16 2012).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Furman J, Hain T. “Do try this at home” Self-treatment of BPPV. Neurology. 2004; 63: 8-9.

- ↑ Nunez R, Cass S, Furman J. Short- and long-term outcomes of canalith repositioning for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. American Academy of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. 2000; 122: 647-652.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Libertory Semont Maneuver for Right BPPV. [Video: Website]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A72UjulJSzE. 2011. (Accessed October 23 2012)

- ↑ Steenerson R, Cronin G. Comparison of the canalith repositioning procedure and vestibular habituation training in forty patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. American Academy of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. 1996; 114: 61-64.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Brain and Spine Foundation. Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises: A Fact Sheet for Patients and Carers. http://www.brainandspine.org.uk/information/publications/brain_and_spine_booklets/vestibular_rehabilitation_exercises/index.html (Accessed October 12 2012).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises. [Video: Website]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXyg9n3nFQk. 2011. (Accessed October 30 2012).

- ↑ Radke A, Neuhauser H, von Brevern M, Lempert T. A modified Epley’s procedure for self-treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 1999; 53: 1358-1360.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Brandt-Daroff Exercises for BPPV Dr. Michael Teixido. [Video: Website]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTZfIv165sY. 2011. (Accessed October 30 2012).

- ↑ Lawson J, Johnson I, Bamiou DE, Newton JL. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: clinical characteristics of dizzy patients referred to a Falls and Syncope Unit. QJM: Journal of International Medicine 2005; 98:357–364.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Pollack L. Awareness of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in central Israel. BMC Neurology 2009; 9:17:9-17.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Scottish Executive. All Our Futures: Planning for Scotland with an Aging Population 2007. www.scotland.gov.uk (accessed 28 October 2012).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 Age Scotland. At Home with Scotland’s Older People: Facts and Figures 2011-2012, 2011 http://www.ageuk.org.uk/documents/en-gb-sc/policy/2011%20at%20home%20with%20scotland's%20older%20people%20-%20%20web%20pdf%20hi-res.pdf?dtrk=true (accessed 20th October 2012)

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 NHS Scotland. Prevention of Falls in Older People 2007. www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/924/0076048.ppt (accessed 20th October 2012)

- ↑ Zur O, Berner YN, Carmeli E. Correlation between vestibular function and hip fracture following falls in the elderly: a case-controlled study. Physiotherapy 2006;92(4):208-213.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Marchetti GF, Whitney SL, Redfern MS, Furman JM. Factors Associated With Balance Confidence in Older Adults With Health Conditions Affecting the Balance and Vestibular System. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011 11;92(11):1884-1891.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006;35(suppl 2):ii37-ii41.

- ↑ Findorff MJ, Wyman JF, Nyman JA, Croghan CF. Measuring the direct healthcare costs of a fall injury event. Nurs Res 2007;56(4):283-287.

- ↑ Kristinsdóttir EK, Jarnlo GB, Magnusson M. Asymmetric vestibular function in the elderly might be a significant contributor to hip fractures. Scand J Rehabil Med 2000;32(2):56-60.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Gananca FF, Gazzola JM, Aratani MC, Perracini MR, Gananca MM. Circumstances and Consequences of Falls in Elderly People with Vestibular Disorder. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol 2006;72(3):388-93.

- ↑ Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2004. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(10):938

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Gananca FF, Gazzola JM, Gananca CF, Caovilla HH, Gananca MM, Cruz OLM.Elderly Falls Associated with Benign Paroxysmal PositionalfckLRVertigo. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol.fckLR2010;76(1):113-20.

- ↑ Imperial College London. Dix-Hallpike Maneuver. [Video: Website] http://www1.imperial.ac.uk/resources/6891997E-5A13-41E7-875B-5982A5F07A87 (Accessed November3 2012).

- ↑ How to Diagnose and Treat Horizontal Canal BPPV EDITED. [Video:Website] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOJOArGmepM. 2012. (Accessed October 15 2012).

- ↑ Imperial College London. Nystagmus Pattern for Right BPPV. [Video:Website] http://www1.imperial.ac.uk/resources/B1C72EE9-92DC-B802-D3B779FE8873/. (Accessed November 2 2012).