Ankle Sprain

Original Editor - Dale Boren, Michael Kauffmann, Pieter Jacobs

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Laura Ritchie, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Michael Kauffmann, Kim Jackson, Pieter Jacobs, Reem Ramadan, Cath Young, Alex Palmer, Roberto Monfermoso, Dale Boren, Andrew Costin, Adam Vallely Farrell, Corentin Meese, Scott Cornish, 127.0.0.1, Scott Buxton, Anas Mohamed, Khloud Shreif, Nupur Smit Shah, WikiSysop, Asha Bajaj, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, Wanda van Niekerk, Anouck Leo, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Kai A. Sigel, Fasuba Ayobami, Tony Lowe, Lisa Parijs, Candace Goh, Shaimaa Eldib and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

An ankle sprain is where one or more of the ligaments of the ankle are partially or completely torn.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

An ankle sprain is a common injury. Inversion-type, lateral ligament injuries represent approximately 85% of all ankle sprains. The incidence of ankle sprain is highest in sports populations. Poor rehabilitation after an initial sprain increases the chances of this injury recurrence[1].

The ankle joint is the body part that is second-most likely to be injured in sport. [2] In the United States of America the total cost of ankle sprains is approximately $2billion[3]. [4]. A meta-analysis by Doherty et al, found that indoor sports carry the greatest risk of ankle sprain with an incidence of 7 per 1,000 cumulative exposures[5]. Severe ankle sprains occur commonly in basketball players. From a study of elite Australian basketball players, McKay et al (2001), reported that the rate of ankle injury was 3.85 per 1000 participations [6]. Recurrence rates amongst basketball players is reported to be greater than 70%[7]. Athletes with chronic ankle instability miss practices and competition, require ongoing care in order to remain physically active, and display sub-optimal performance.

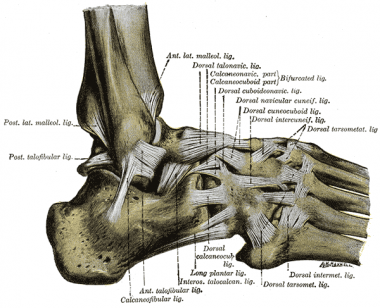

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Of the lateral ankle ligament complex the most frequently damaged one is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL). Their anatomical location and the mechanism of sprain injury mean that the calcaneo-fibular (CFL) and posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFL) are less likely to sustain damaging loads.

| [8] |

On the medial side the strong, deltoid ligament complex [posterior tibiotalar (PTTL), tibiocalcaneal (TCL), tibionavicular (TNL) and anterior tibiotalar ligaments (ATTL)] is injured with forceful "pronation and rotation movements of the hindfoot". [9]

The stabilising ligaments of the distal tibio-fibular syndesmosis are the anterior-inferior, posterior-inferior, and transverse tibio-fibular ligaments, the interosseous membrane and ligament, and the inferior transverse ligament. A syndesmotic (high ankle) sprain occurs with combined external rotation of the leg and dorsiflexion of the ankle.

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Several intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors predispose an athlete to chronic ankle instability. The most common risk factor is previous history of sprain. A previous sprain may compromise the strength and integrity of the stabilisers and interrupt sensory nerve fibres[10]. Sex, height, weight, limb dominance, postural sway and foot anatomy are intrinsic. Extrinsic risk factors may include taping, bracing, shoe type, competition duration and intensity of activity.

Mechanism of injury/pathological process[edit | edit source]

Lateral ankle sprains usually occur during a rapid shift of body center of mass over the landing or weight-bearing foot. The ankle rolls outward, whilst the foot turns inward causing the lateral ligament to stretch and tear. When a ligament tears or is overstretched its previous elasticity and resilience rarely returns. Some researchers have described situations where return to play is allowed too early, compromising sufficient ligamentous repair[11] Reports have proposed that the greater the level of plantar flexion the higher the likelihood of sprain[12] Yeung et al, 1994, in an epidemiological study of unilateral ankle sprains, reported that the dominant leg is 2.4 times more vulnerable to sprain than the non-dominant one. [7] [1]. A less common mechanism of injury involves forceful eversion movement at the ankle injuring the strong deltoid ligament.

| Aspect | Mechanism of injury | Ligaments |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral | Inversion and plantarflexion | anterior talofibular ligament calcaneo-fibular ligament posterior talofibular ligament |

| Medial | Eversion | posterior tibiotalar ligament tibiocalcaneal ligament tibionavicular ligament anterior tibiotalar ligament |

| High | External rotation and dorsiflextion | anterior-inferior tibiofibular ligament posterior-inferior tibiofibular ligamen transverse tibiofibular ligament interosseous membrane interosseous ligament inferior transverse ligament |

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

- Patient presents with inversion injury or forceful eversion injury to the ankle. May have previous history of ankle injuries or instability.

- Able to partial weight-bear only on the affected side.

- If patient presents with description of cold foot or paraesthesia, suspect neurovascular compromise of peroneal nerve.

- Tenderness, swelling and bruising can occur on either side of the ankle.

- No bony tenderness, deformity or crepitus present.

- Passive inversion or plantar flexion with inversion should replicate symptoms for a lateral ligament sprain. Passive eversion should replicate symptoms for a medial ligament sprain.

- Special Tests: +ve Anterior Draw, Talar Tilt or Squeeze Test (depending on the structures involved)

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

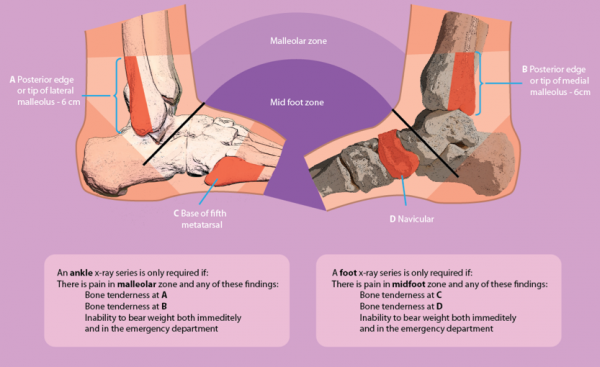

The Ottawa Ankle Clinical Prediction Rules are an accurate tool to exclude fractures within the first week after an ankle injury.[13]

Additional differential diagnosis to look out for:[14]

- Impingement

- Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

- Sinus Tarsi Syndrome

- Cartilage or psteochondral injuries

- Peroneal Tendinopathy or subluxation

- Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

Classification grading systems[edit | edit source]

There are numerous grading systems used for the classification of ligament sprains, each having their strengths and weaknesses. Different therapists may employ different systems so effective continuity of care, the patient should see the same therapist each time. Authors do not always disclose which system they used, reducing rigour and quality of some research[15].

The traditional grading system for ligament injuries focuses on a single ligament[15]

- Grade I represents a microscopic injury without stretching of the ligament on a macroscopic level.

- Grade II has macroscopic stretching, but the ligament remains intact.

- Grade III is a complete rupture of the ligament.

As there are ankle multiple ligaments across the joint it may not be always straight forward to use a grading system that is designed for describing the state of a single ligament unless it is certain that only a single ligament is injured.

Some authors have therefore resorted to grading lateral ankle ligament sprains by the number of ligaments injured[16]. It is, however, hard to be certain on the number of ligaments torn unless there is clear, high quality radiographic or surgical evidence.

A third system which can be adopted is a 3 graded classification based on the severity of sprain injury[15].

- Grade I Mild - Little swelling and tenderness with little impact on function

- Grade II Moderate - Moderate swelling, pain and impact on function. Reduced proprioception, ROM and instability

- Grade III Severe - Complete rupture, large swelling, high tenderness loss of function and marked instability

This scale is largely subjective due to individual therapist interpretation. However, the same can be said for the other classifications unless clear radiographic evidence is available or assessed and treated by surgical intervention.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)

Clinical Examination[edit | edit source]

With an ankle sprain multiple structures may be involved, therefore a full foot and ankle assessment is recommended[15], including the mechanism of injury, observation of the patient's gait pattern, standing posture and wear on the individual's shoes.[17] Any gross deformity, mal-alignment or atrophy of the musculature should also be observed and noted as well as any oedema and/or ecchymosis.

Palpation is used to feel for the structures that may be involved in the injury, including bone, muscle and ligamentous structures, followed by an active and passive range of movement assessment.

| [18] | [19] |

Special Tests[edit | edit source]

- Anterior Draw - tests the ATFL

- Talar Tilt - tests the CFL

- Posterior Draw - tests the PTFL

- Squeeze test - for syndesmotic sprain

- External rotation stress test (Kleiger’s test) - syndesmotic sprain

| [20] | [21] |

It is recommended that these tests be performed at 4-7 days post acute injury to allow the initial swelling and pain to settle, enabling the therapist to gain a more accurate diagnosis[15].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Mild ankle sprain

- Natural full recovery within 14 days

- Taping and follow up to evaluate healing progression[13][22](level of evidence: 1a)

First time lateral ligament sprains can be innocuous injuries that resolve quickly with minimal intervention and some approaches suggest that only minimal intervention is necessary. The NICE guidelines 2016 recommend advice and analgesia, but not routine physiotherapy referrals[23]. However, it has has also been highlighted that recurrence rate of first time lateral ankle sprains is 70%[24](level of evidence: 3b). With the recurrence rate so high and the guidelines not recommending any rehabilitation, this approach has been questioned[25](level of evidence: 2b).

Severe Ankle Sprain

Physiotherapy is required with functional therapy of the ankle shown to be more efficient than immobilisation. Functional therapy treatment can be divided in 4 stages, moving onto to the next stage as tissue healing allows [13](level of evidence: 1a)

- Inflammatory phase,

- Proliferative phase,

- Early Remodelling,

- Late Maturation and Remodelling. [13][22][26](level of evidence 1a)[27](level of evidence: 1a)

Inflammatory Phase (0-3 days)[edit | edit source]

Goals:[edit | edit source]

Reduction of pain and swelling and improve circulation and partial foot support

The most common approach to manage ankle sprain is the PRICE protocol: Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation[28] (Level of evidence 5)

Recommendations for the Patient:

- Protection: Protect the ankle from further injury by resting and avoiding activities that may cause further injury and/or pain

- Rest: Advise rest for the first 24 hours after injury, possibly with crutches to offload the injured ankle and altering work and sport and exercise requirements as needed

- Ice: Apply a cold application (15 to 20 minutes, one to three times per day)

- Compression: Apply compression bandage to control swelling caused by the ankle sprain

- Elevation: Ideally elevate ankle above the level of the heart, but as a minimum, avoid positions where the ankle is in a dependent position relative to the body

Despite its widespread clinical use, the precise physiologic responses to ice application have not been fully elucidated. Moreover, the rationales for its use at different stages of recovery are quite distinct. There is insufficient evidence available from RCTs to determine the relative effectiveness of RICE therapy for acute ankle sprains in adults. But no evidence exist to reject the RICE protocol. [29] (Level of evidence 1a)

Foot and Ankle ROM:

- Patient performs active movements with the toes and ankle within pain free limits to improve local circulation. [22][30](level of evidence 1b)[31](level of evidence 1a)

- Manual therapy in the acute phase could also effectively increase ankle dorsiflexion. [32] (Level of evidence 3a)

- Anteroposterior manipulation and RICE results in greater improvement in range of movement than the application of RICE alone. [33] (Level of evidence 1b)

Proliferative Phase (4-10 days)[edit | edit source]

Goals:[edit | edit source]

Recovery of foot and ankle function and improved load carrying capacity.

1. Patient education regarding gradual increase in activity level, guided by symptoms.

2. Practise Foot and Ankle Functions

- Range of Motion

- Active Stability

- Motor Coordination

It is important to begin early with the rehabilitation of the ankle. First week exercises produce significant improvements to short term ankle function.[34](level of evidence 1b)

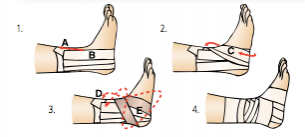

3. Tape/Brace :

- Apply tape as soon as the swelling has decreased.

- Tape or a brace use depends on patient preference

- Boyce et al found that the use of an Aircast ankle brace for the treatment of lateral ligament ankle sprains produces a significant improvement in ankle joint function compared with standard management with an elastic support bandage.[35](level of evidence 2b)

- It remains uncertain, however, which treatment (brace, bandage or tape) is most beneficial. [13]

Two examples of ankle sprain taping techniques, but there are many other different techniques.

| [36]( | [37](l |

Early Remodelling (11 -21 days)[edit | edit source]

Goals: [edit | edit source]

Improve muscle strength, active (functional) stability, foot/ankle motion, mobility (walking, walking stairs, running).

Education:

- Provide information about possible preventive measures (tape or brace)

- Advice regarding appropriate shoes to wear during sport activities, in relation to the type of sport and surface

Practise foot and ankle functions (See Resource Videos below)

- Practice balance, muscle strength, ankle/foot motion and mobility (walking, stairs, running).

- Look for a symmetric walk pattern.

- Work on dynamic stability as soon as loa -bearing capacity allows, focusing on balance and coordination exercises. Gradually progress the loading, from static to dynamic exercises, from partially loaded to fully loaded exercises and from simple to functional multi-tasking exercises. Alternate cycled with non-cycled exercises (abrupt, irregular exercises). Use different types of surfaces to increase the level of difficulty.

- Encourage the patient to continue practicing the functional activities at home with precise instructions regarding the expectations for each exercise.

Taping/bracing

- Advise wearing tape or a brace during physical activities until the patient is able to confidently perform static and dynamic balance and motor coordination exercises.

Late Remodelling and Maturation[edit | edit source]

Goals:[edit | edit source]

Improve the regional load-carrying capacity, walking skills and improve the skills needed during activities of daily living as well as work and sports.

Practise and adjust foot abilities (functions and activities)

- Practise motor coordination skills while performing mobility exercises

- Continue to progress the load-bearing capacity as described above until the pre-injury load-carrying capacity is reached

- Increase the complexity of motor coordination exercises in varied situations until the pre-injury level is reached

- Encourage the patient to continue practicing at home

Chronic Ankle Instability[edit | edit source]

On-going issues following a lateral ligament injury within the ankle are reported in 19-72% of patients. An ability to complete certain movement tasks, evidence of deficits during the Star Excursion Balance Test and self-reported function as quantified using the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure can be utilised as predictive measures of a Chronic Ankle Instability (CAI) outcome in the clinical setting for patients with a first time lateral ankle sprain injury[38]. Around 20% of people develop CAI and this has been attributed to a delayed muscle reflex of stabilising lower leg muscles, deficits in lower leg muscle strength, deficits in kinaesthesia or impaired postural control[39](level of evidence 1a)[40].(level of evidence 1a)

Chronic ankle instability has been describes as a combination of mechanical (pathological laxity, arthrokinematic restrictions, and degenerative and synovial changes) and functional (Impaired proprioception and neuromuscular control, and strength deficits) insufficiencies[41].(level of evidence 1a) A sound treatment program must adhere to both mechanical and functional insufficiencies.

It is recommended that all patients undergo conservative treatment to improve stability and improve the muscle reflex and strength of the lower limb stabilising muscles. Although this will help some individuals, it cannot compensate for the defecit of the lateral ligament complex and surgery is occasionally required[39].(level of evidence 1a)

Ankle Bracing and Taping[edit | edit source]

Ankle Bracing and taping is often used as a preventative measure which has gained increasing research. Ankle taping may be used to help stabilise the joint by limiting motion and proprioception. Ankle taping is said to have a greater effect in preventing recurrent strains rather than an initial sprain[6].(level of evidence 3b) A study on basketball players detailed the effectiveness of ankle taping on reducing the risk of re-injury in athletes who have a history of ankle-ligament sprains. The large sample size of the study (n=10,393) and identification of 40 ankle injuries adds reliability to the results expressed. Tropp et al, 1985, undertook a study in soccer players who wore an ankle brace. The subjects in the brace group experienced a significant decrease in the incidence of ankle sprains when compared to no intervention[42].(level of evidence 3b) Surve et al, 1994, described similar effects in their prospective study with bracing but noted there was no difference in the ankle sprain severity in the braced and unbraced groups[43].(level of evidence 1b)

Reports are inconclusive on the effective of ankle taping. Several reports have suggested the ineffectiveness of taping[6] (level of evidence 3b)[44].(level of evidence 3b) It’s effectiveness is also affected by the experience of the taper. Some of the advantages of bracing over taping are; cost[45],(level of evidence 2a) reusability, no expertise is required for application and minimal effect of an allergic reaction[46].(level of evidence 2a)

Resources[edit | edit source]

- The Sprained Ankle from the Connecticut Centre for Orthopedic Surgery contains a range of resources on Ankle Sprains including patient resources and surgical techniques.

Coordinated Health TV Ankle Sprain Video Series

| [47] | [48] | [49] |

Denver-Vail Orthopedics, P.C Ankle Sprain Video Series

| [50] | [51] |

| [52] | [53] |

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Physical Therapy Management of Acute Ankle Sprain

This presentation was created by Rich Westrick and Cody McAndrew as part of the Regis University OMPT Fellowship. Physical Therapy Management of Acute Ankle Sprain/ View the presentation |

|

PT in Injury Prevention: Ankle Sprains

This presentation was created by Sumesh Thomas as part of the Regis University OMPT Fellowship. PT in Injury Prevention: Ankle Sprains/ View the presentation |

|

Current Best Evidence: Management of Chronic Ankle Sprain

This presentation was created by Cheryl Sparks as part of the Regis University OMPT Fellowship. Current Best Evidence: Management of Chronic Ankle Sprain/ View the presentation |

Error: Image is invalid or non-existent. |

Current Best Evidence: Management of Chronic Ankle Sprain

This presentation was created by Chris Kramer as part of the Regis University OMPT Fellowship. Current Best Evidence: Management of Chronic Ankle Sprain/ View the presentation |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Roos KG, Kerr ZY, Mauntel TC, Djoko A, Dompier TP, Wickstrom EA. The epidemiology of lateral ligament complex ankle sprains in National Collegiate Athletic Association sports. American journal of sports medicine. 2016.The American Journal of Sports Medicine Vol 45, Issue 1, pp. 201 - 209

- ↑ Fong, D. T. P., Hong, Y., Chan, L. K., Yung, P. S. H., & Chan, K. M. (2007).

- ↑ Soboroff, S. H., Pappius, E. M., & KOMAROFF, A. L. (1984). Benefits, risks, and costs of alternative approaches to the evaluation and treatment of severe ankle sprain. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 183, 160-168.

- ↑ A systematic review of ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Medicine, 37(1), 73-94.

- ↑ Doherty, C., Delahunt, E., Caulfield, B., Hertel, J., Ryan, J., & Bleakley, C. (2014). The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. Sports medicine, 44(1), 123-140.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 McKay GD, Goldie PA, Payne WR, Oakes BW. Ankle injuries in basketball: injury rate and risk factors. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:103–108.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Yeung, M. S., Chan, K. M., So, C. H., & Yuan, W. Y. (1994). An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. British journal of sports medicine, 28(2), 112-116.

- ↑ Dr Glass DPM. Ankle Sprain Injury Explained. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_u5w856Yjvg [last accessed 28/08/12]

- ↑ Malleolar fractures: nonoperative versus operative treatment. A controlled study. Bauer M, Bergström B, Hemborg A, Sandegård J. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985 Oct; (199):17-27.

- ↑ Beynnon, B. D., Murphy, D. F., & Alosa, D. M. (2002). Predictive factors for lateral ankle sprains: a literature review. Journal of athletic training, 37(4), 376.

- ↑ Hubbard, T. J., & Hicks-Little, C. A. (2008). Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. Journal of athletic training, 43(5), 523.

- ↑ Wright, I. C., Neptune, R. R., van den Bogert, A. J., & Nigg, B. M. (2000). The influence of foot positioning on ankle sprains. Journal of biomechanics, 33(5), 513-519.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Van der Wees PJ, Lenssen AF, Feijts YAEJ, Bloo H, van Moorsel SR, Ouderland R, et al. KNGF-Guideline for Physical Therapy in patients with acute ankle sprain. Dutch J Phys Ther. 2006; 116(Suppl 5):**. Available from: https://www.kngfrichtlijnen.nl/images/imagemanager/guidelines_in_english/KNGF_Guideline_for_Physical_Therapy_in_patients_with_Acute_Ankle_Sprain.pdf (accessed 29 Aug 2012).

- ↑ GP Online (2007). Differential diagnosis of common ankle injuries, Available at: http://www.gponline.com/differential-diagnosis-common-ankle-injuries/article/766219 (Accessed: 24th Aug 2014).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Lynch S. Assessment of the Injured Ankle in the Athlete. J Athl Train 2002 37(4) 406-412

- ↑ Gaebler C, Kukla C, Breitenseher M J, et al. Diagnosis of lateral ankle ligament injuries: comparison between talar tilt, MRI and operative findings in 112 athletes. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:286–290

- ↑ Anthony L. Ankle Physical Examination, Available at: http://orthosurg.ucsf.edu/oti/patient-care/divisions/sports-medicine/conditions/physical-examination-info/ankle-physical-examination/ (Accessed: 24 Aug 2014).

- ↑ Via Christi. Musculoskeletal Physical Exam: Ankle. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QiSm8rz2cmo [last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Massage Therapy Practise. Ankle Palpation. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uI8Z0obhpew [last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Physiotutors. Anterior Drawer Test (Ankle)⎟Lateral Ankle Sprain. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mZIqricuKjE

- ↑ Physiotutors. The Talar Tilt Test | Lateral Ankle Sprain. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHNbm6Z3XK4

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Fongemie A, Dudero A, Standemo G, Stovitz S, Dahm D, THomas A, et al. Health Care Guideline [Internet]. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Health care guideline: ankle sprain. 7th ed. 2006. Available from: http://www.icsi.org/ankle_sprain/ankle_sprain_4.html (accessed 29 Aug 2012)

- ↑ NICE, 2016. Sprains and Strains. https://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario [accessed 5 January 2016]

- ↑ Sefton JM, Hicks-Little CA, Hubbard TJ, Clemens MG, Yengo CM, Koceja DM, Cordova ML. Sensorimotor function as a predictor of chronic ankle instability. Clinical Biomechanics. 2009 Jun 30;24(5):451-8.

- ↑ Doherty C, Bleakley C, Hertel J, Caulfield B, Ryan J, Delahunt E. Recovery From a First-Time Lateral Ankle Sprain and the Predictors of Chronic Ankle Instability A Prospective Cohort Analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Apr 1;44(4):995-1003

- ↑ Van der Wees PJ, Lenssen AF, Hendriks EJM, Stomp DJ, Dekker J, de Brie RA. Effectiveness of exercise therapy and manual mobilisation in acute ankle sprain and functional instability: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006; 52:27-37. Available from: http://svc019.wic048p.server-web.com/ajp/vol_52/1/AustJPhysiotherv52i1van_der_Wees.pdf (accessed 29 Aug 2012)

- ↑ Kerkhoffs GM, Rowe BH, Assendelft WJ, Kelly KD, Struijs PA, van Dijk CN. Immobilisation for acute ankle sprain. A systematic review.. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121(8):462-71. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/content/knrf19kk4tvc266/ (Level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Balduini FC, Vegso JJ, Torg JS, et al. Management and rehabilitation of ligamentous injuries to the ankle. Sports Med. 1987;4(5):364-380. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3313619 (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ van den Bekerom MP1, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM., What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?. Journal of Athletic Training. 2012 Jul-Aug;47(4):435-43https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22889660 (Level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Bleakley CM, O'Connor S, Tully MA, Rocke LG, MacAuley DC, McDonough S. The PRICE study (Protection Rest Ice Compression Elevation): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing standard versus cryokinetic ice applications in the management of acute ankle sprain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007; 8:125. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2474-8-125.pdf (accessed 29 Aug 2012)

- ↑ Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft-tissue injury. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1):251-61. Available from: http://www.smawa.asn.au/_uploads/res/120_3630.pdf (accessed 29 Aug 2012)

- ↑ Bleakley CM, McDonough SM, MacAuley DC., Some conservative strategies are effective when added to controlled mobilisation with external support after acute ankle sprain: a systematic review., The Australian journal of physiotherapy. 2008;54(1):7-20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18298355/ (Level of evidence 3a)

- ↑ Green T1, Refshauge K, Crosbie J, Adams R., A randomized controlled trial of a passive accessory joint mobilization on acute ankle inversion sprains., Physical Therapy, 2001 April, 81(4):984-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11276181/ (Level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Chris M Bleakley et al., Effect of accelerated rehabilitation on function after ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial., BMJ, 2010. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c1964 (Level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Boyce SH, Quigley MA, Campbell S. Management of ankle sprains: a randomised controlled trial of the treatment of inversion injuries using an elastic support bandage or an Aircast ankle brace. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(2):91-6. Available from: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/39/2/91.full.pdf+html (Level of evidence 2b)

- ↑ Finest Physio. Finest Physio: Ankle Taping. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_XlzZMSV8E [last accessed 09/12/12]

- ↑ itherapies. Mulligan Taping Techniques: Inversion Ankle Sprain. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEjKhf-qDJU [last accessed 09/12/12]

- ↑ Doherty C, Bleakley C, Hertel J, Caulfield B, Ryan J, Delahunt E. Recovery from a first-time lateral ankle sprain and the predictors of chronic ankle instability: a prospective cohort analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Apr;44(4):995-1003.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Al-Mohrej OA, Al-Kenani NS. Chronic ankle instability: Current perspectives. Avicenna journal of medicine. 2016 Oct;6(4):103.

- ↑ Eechaute C, Vaes P, Van Aerschot L, Asman S, Duquet W. The clinimetric qualities of patient-assessed instruments for measuring chronic ankle instability: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Jan 18;8(1):1.

- ↑ Hertel, J. (2002). Functional anatomy, pathomechanics, and pathophysiology of lateral ankle instability. Journal of athletic training, 37(4), 364.

- ↑ Tropp H, Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. Stabilometry in functional instability of the ankle and its value in predicting injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16:64–66.

- ↑ Surve I, Schwellnus MP, Noakes T, Lombard C. A fivefold reduction in the incidence of recurrent ankle sprains in soccer players using the Sport- Stirrup orthosis. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:601–606.

- ↑ Rovere, G. D., Clarke, T. J., Yates, C. S., & Burley, K. (1988). Retrospective comparison of taping and ankle stabilizers in preventing ankle injuries. The American journal of sports medicine, 16(3), 228-233.

- ↑ Olmsted, L. C., Vela, L. I., Denegar, C. R., & Hertel, J. (2004). Prophylactic ankle taping and bracing: a numbers-needed-to-treat and cost-benefit analysis. Journal of athletic training, 39(1), 95.

- ↑ Callaghan, M. J. (1997). Role of ankle taping and bracing in the athlete. British journal of sports medicine, 31(2), 102-108.

- ↑ Coordinated Health TV. Ankle Sprains Part 1: Anatomy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDFbZFNtPfs[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Coordinated Health TV. Ankle Sprains Part 2: Symptoms & Evaluation. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dP17ZY3zxa4 [last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Coordinated Health TV. Ankle Sprains Part 3: Rehab & Protection. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dznWBbwLq6k[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 1 How they occur, what ligaments are injured and initial treatment. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B0-n-ndTAX0[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 2 Stretching and Range of Motion Exercises. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHJbvf4TW2Y[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 3 Stretching and Range of Motion Exercises. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6xRWb9dFbU[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 4 Proprioception - Balance. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AsEV5OYghSQ[last accessed 24/03/2015]