Tension-type headache

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Laure Lievens, Admin, Fasuba Ayobami, Emma Guettard, Vanessa Rhule, Astrid Lahousse, Kim Jackson, Kapil Narale, Elaine Lonnemann, Jacquelyn Brockman, Vidya Acharya, Grite Apanaviciute, Anouk Van den Bossche, Jonathan Wong and Ahmed M Diab

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Tension-type headache (TTH) is a neurological disorder characterized by headache attacks ranging in severity from mild to moderate, dull aching bilateral pain around the temporal region, feeling not unlike a pressing or tightening band (that is non-pulsating) around the forehead, neck, shoulder, and sometimes behind the eyes[2]. Their associated symptoms will be discussed further in the ‘Characteristics’[3] section below. Diagnosis criteria for TTH is based on the International Headache Society classification. This is discussed further under the ‘Diagnostic Procedures’ section below.

TTH is the most common type of primary headache[4]: its lifetime prevalence in the general population ranges in different studies from 30 to 78%. At the same time, it is the least studied of the primary headache disorders, despite the fact that it has the highest socio-economic impact, imposing a heavy burden on the global population. Despite this, they remain poorly managed and incompletely understood.

The exact mechanism behind TTH is unknown. Peripheral pain mechanisms are most likely to play a role in infrequent episodic TTH and frequent episodic TTH, whereas central pain mechanisms play a more important role in Chronic TTH.[1][3]According to the Global Burden of Disease (2019), tension-type headaches (TTH) have an estimated worldwide prevalence at an average of 26.0% (22.7–29.5%), with 23.4% in men and 27.1% in women[5].

Classification of Tension-type headaches[edit | edit source]

All subtypes of tension-type headaches share common characteristics: bilateral non-pulsating pain, with mild to moderate intensity that does not worsen with movement or is associated with nausea or vomiting[6]. Mild nausea exclusively appears in the Chronic Tension-type Headache[6]. Pain is focused around the parietal, frontal and suboccipital regions[7].

Infrequent episodic[edit | edit source]

The infrequent subtype has episodes less than once per month and has very little impact on the individual. The pain is typically bilateral, pressing, or tightening in quality and mild to moderate intensity. It is not worsened with physical activity. There is no nausea, but photophobia or phonophobia may be present.[8] It can be further classified into;

- Infrequent episodic tension-type headache associated with pericranial tenderness: Episodes fulfil the criteria for infrequent episodic tension-type headache, which is discussed under the Diagnostic Procedures of this topic. In addition, there is an increased pericranial tenderness on palpation[9].

- Infrequent episodic tension-type headache not associated with pericranial tenderness: Episodes fulfil the criteria for infrequent episodic tension-type headache, which is discussed under the Diagnostic Procedures of this topic. But there is no increase in pericranial tenderness[9]

Frequent episodic[edit | edit source]

Frequent episodes of headache, typically bilateral, pressing or tightening in quality and of mild to moderate intensity, lasting minutes to days. The pain does not worsen with routine physical activity and is not associated with nausea, although photophobia or phonophobia may be present[9]. It can be further divided into:

- Frequent episodic tension-type headache associated with pericranial tenderness: Episodes fulfil the criteria for frequent episodic tension-type headache, which is discussed under the Diagnostic Procedures of this topic. In addition, there is an increased pericranial tenderness on manual palpation.[9]

- Frequent episodic tension-type headache not associated with pericranial tenderness: Episodes fulfil the criteria for frequent episodic tension-type headache, which is discussed under the Diagnostic Procedures of this topic. But there is no increase in pericranial tenderness.[9]

Chronic tension-type headaches[edit | edit source]

A disorder evolving from frequent episodic tension-type headache, with daily or very frequent episodes of headache, typically bilateral, pressing or tightening in quality and of mild to moderate intensity, lasting hours to days, or unremitting. The pain does not worsen with routine physical activity, but may be associated with mild nausea, photophobia or phonophobia.[9] It can be further classified as:

- Chronic tension-type headache associated with pericranial tenderness: Episodes fulfil the criteria for chronic tension-type headache, which is discussed under the Diagnostic Procedures of this topic. In addition, there is an increased pericranial tenderness on manual palpation.[9]

- Chronic tension-type headache not associated with pericranial tenderness: Episodes fulfil the criteria for chronic tension-type headache, which is discussed under the Diagnostic Procedures of this topic. But there is no increase in pericranial tenderness.[9]

Probable tension-type headache[edit | edit source]

Tension-type-like headache missing one of the features required to fulfil all criteria for a type or subtype of tension-type headache coded above, and not fulfilling criteria for another headache disorder[9]. It can be further divided into three categories namely:

- Probable infrequent episodic tension-type headache: One or more episodes of headache fulfilling all but one of criteria 1-4 for Infrequent episodic tension-type headache. Not fulfilling ICHD-3 criteria for any other headache disorder. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.[9]

- Probable frequent episodic tension-type headache: Episodes of headache fulfilling all but one of criteria 1-4 Frequent episodic tension-type headache. Not fulfilling ICHD-3 criteria for any other headache disorder. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.[9]

- Probable chronic tension-type headache: Headache fulfilling all but one of criteria 1-4 for Chronic episodic tension-type headache. Not fulfilling ICHD-3 criteria for any other headache disorder. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis[9].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The brain itself is insensitive to pain, so that is not what hurts when a headache arises.

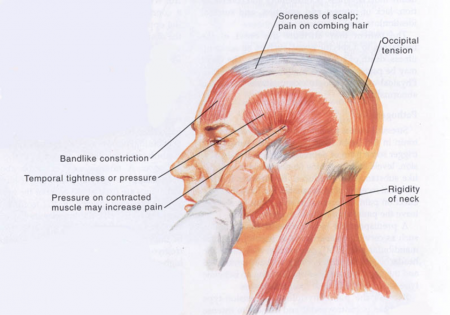

The pain instead occurs in the following locations:

- The tissues covering the brain.

- The attaching structures at the base of the brain.

- Muscles and blood vessels around the scalp, face, and neck.

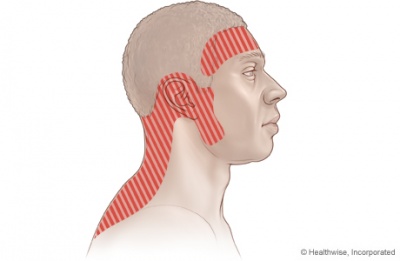

The pain is commonly described as a tight feeling, as if the head were in a vise. It usually occurs on both sides of the head and is often experienced in the forehead, in the back of the head and neck, or in both regions. Soreness in the shoulders or neck is common. The muscles who are tight in the frontal and temporal region are: the masseter, pterygoid, sternocleidomastoid, splenius and trapezius muscles.

Most of all the pain the patient feels is in the following area:

- The pain is of mild-to-moderate intensity and is steady, not throbbing or pulsating.

- The headache is not accompanied by nausea or vomiting.

- The pain is not worsened by routine physical activity (climbing stairs, walking).

- Some patients may have either sensitivity to light or sensitivity to noise, but not both.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The causes of tension-type headache remain poorly understood. Although tension-type headaches were once thought to be primarily due to muscle contractions, this theory has largely been discounted. Instead, researchers think that tension-type headaches occur due to an interaction of different factors that involve pain sensitivity and perception, as well as the role of brain chemicals (neurotransmitters). Genetic factors are likely be involved in chronic tension-type headache, whereas environmental factors (physical and psychological stress) may play a role in the physiologic processes involved with episodic tension-type headache.

Pain Sensitivity and perception

Research indicates that patients with tension-type headache may have abnormalities in the central nervous system, which includes the nerves in the brain and spine, that increase their sensitivity to pain[10].

Brain Chemicals (neurotransmitters)

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers in the brain. Several types of neurotransmitters have been identified as playing a role in increasing activity in pain pathways in the brain and affecting how the brain reacts to pain stimulation. In particular, serotonin (also called 5-HT) and nitric oxide are thought to be involved in these chemical changes. Release of these chemicals may activate nerve pathways in the brain, muscles, or elsewhere and increase pain.

Myofascial tenderness and hardness in THH

Tension-type headaches may also be linked to myofascial trigger points in the neck and shoulder muscles. Studies have consistently shown that the pericranial myofascial tissues are considerably more tender in patients with TTH than in healthy subjects, and that the tenderness is positively associated with both the intensity and the frequency of TTH episodes. Tenderness is uniformly increased throughout the pericranial region in both episodic and chronic subtypes of TTH. It has also been demonstrated that the pericranial muscles are harder on palpation, suggesting tension. Muscle tension is suggested as one of the main causes of TTH, which could be a result of stress and/or anxiety[2]. Tenderness and hardness have been found to be increased both on days with and on days without headache suggesting that these factors are of importance for the development of headache and not only a consequence of the headache.[11]

Prevalence:

The lifetime prevalence in the general population ranges in different studies from 30 to 78%. In a population-based study in Denmark the lifetime prevalence of TTH was high (78%), but the majority had episodic infrequent TTH (1 day a month or less) without specific need for medical attention.[12] About 24% to 37% had TTH several times a month, 10% had it weekly, and 2% to 3% of the population had chronic TTH, usually lasting for the greater part of a lifetime.[12]

Age and sex:

In contrast to migraine, in TTH, women are only slightly more affected than male (the female-to-male ratio of TTH is 5:4) and the average age of onset (25 to 30 years) is delayed. The peak prevalence occurs between ages 30 to 39 and decreases slightly with age.[12]

For children it has been estimated that around 6.1% to 13.6% suffer from migraine and 9.8% to 24.7% suffer from tension-type headache (TTH).[13]

TTH patients have a future risk of dementia, indicating a potentially linked disease pathophysiology that warrants further study. The association between TTH and dementia is greater in women, older adults, and with comorbidities. Clinicians should be aware of potential dementia comorbidity in TTH patients.[14]

Infrequent episodic tension-type headache is primarily caused by environmental factors, while frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache is caused partly by genetic factors. It is expected that identification of genetic markers will be difficult due to multifactorial inheritance.[15]

Risk factors:

TTH was associated with smoking during pregnancy, parent-reported total difficulties at age 3.5 years, higher percent body fat, and being bullied at age 11.[13]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis for tension-type headache in the general population is favourable: 45% of adults with frequent or chronic tension-type headache at baseline were in remission when examined three years later, although 39% still had frequent headaches, and 16% had chronic tension-type headache. Poor outcome was associated with the presence of chronic tension-type headache at baseline, coexisting migraine, not being married, and sleep problems. Predictive factors for remission were older age and absence of chronic tension-type headache at baseline. The prognosis for patients who need medical intervention or specialist headache care is presumably not so favourable but is difficult to determine because case mix varies considerably from clinic to clinic and country to country.[3]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis TTH and migraine:[edit | edit source]

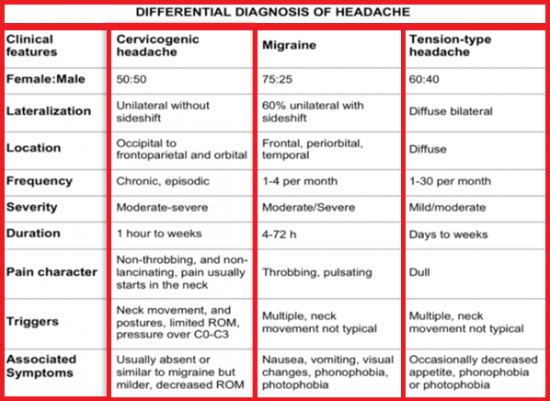

Migraines and tension headaches have some similar characteristics, but also some important differences[16]:

- Migraine pain is usually throbbing, while tension-type headache pain is usually a steady ache

- Migraine pain often affects only one side of the head, while tension-type headache pain typically affects both sides of the head

- Migraine headaches, but not tension-type headaches, may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting, sensitivity to light and sound, or aura

Some other differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Other possible differential diagnoses include: [12]

- Medication-overuse headache: History of previous primary headache. Use of analgesics and ergotamine at a high frequency and worsening of headache on discontinuation of medication. Over several months, frequency and duration increases such that attacks become daily or near daily, although not necessarily more severe. Opioids and barbiturate-containing analgesics most commonly produce this syndrome.

- Sphenoid sinusitis: Vertex or frontal pain, often described as pressure, but not necessarily with additional sinus symptoms.

- Giant cell arteritis: Generally over 50 years of age. New head pain associated with soreness of the scalp; polymyalgia rheumatica and often jaw or tongue claudication.

- Temporomandibular disorder (TMD): Pain over temporalis associated with noise and clicking over TMJ with jaw movement. Often associated with bruxism and limited jaw movements, or pain or locking of the jaw with opening of mouth.

- Pituitary tumor: Abnormal neurologic examination. Visual field defects and galactorrhea may occur.

- Brain tumor: Abnormal neurologic examination including reflex asymmetry, sensory asymmetry, or motor weakness. Papilledema suggests an intracranial mass lesion.

- Chronic subdural hematoma: Abnormal mentation, abnormal neurologic examination including reflex asymmetry, sensory asymmetry, or motor weakness.

- Pseudotumor cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension): As well as papilledema, there may be reduced visual acuity, visual field defect (enlarged blind spot), or diplopia caused by a sixth nerve palsy. CSF pressures are abnormal and are increased to >200 mm water in nonobese and >250 mm water in obese people.

- Cervical pathology: Rarely, serious cervical pathology such as a herniated disk may contribute to headache.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic criteria for the subtypes of tension-type headache from the IHS classification[9]

Diagnostic criteria for Infrequent episodic tension-type headache:[edit | edit source]

1. At least 10 episodes occurring on <1 day per month on average (<12 days per year) and fulfilling criteria 2-4

2. Headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days

3. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

-bilateral location

-pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality

-mild or moderate intensity

-not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

4. Both of the following:

-no nausea or vomiting (anorexia may occur)

-no more than one of photophobia or phonophobia

5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Diagnostic criteria for Frequent episodic tension-type headache:[edit | edit source]

1. At least 10 episodes occurring on ≥1 but <15 days per month for at least 3 months (≥12 and <180 days per year) and fulfilling criteria

2. Headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days

3. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

-bilateral location

-pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality

-mild or moderate intensity

-not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

4. Both of the following:

-no nausea or vomiting (anorexia may occur)

-no more than one of photophobia or phonophobia

5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Diagnostic criteria for Chronic tension-type headache:[edit | edit source]

1. Headache occurring on ≥15 days per month on average for >3 months (≥180 days per year)1 and fulfilling criteria 2-4

2. Headache lasts hours or may be continuous

3. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

-bilateral location

-pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality

-mild or moderate intensity

-not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

4. Both of the following:

-no more than one of photophobia, phonophobia or mild nausea

-neither moderate or severe nausea nor vomiting

5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- HARDSHIP: The Headache-Attributed Restriction, Disability, Social Handicap and Impaired Participation questionnaire which is designed for application by medical or trained interviewers. HARDSHIP integrates diagnostic questions (these are based on ICHD-3 β criteria), demographic enquiry and investigate the several components of headache-attributed burden: symptom burden, health-care utilization, disability and productive time loss, the impact on education and earnings, perception of control, interictal burden, overall individual burden, effects on relationships and family, effects on other people including household partner and children, quality of life, wellbeing, obesity as a comorbidity.[17]

- Quality of life: WHOQoL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire-BREF). This is an shortened version of the WHOQoL-100 developed by The World Health Organization. It’s a self-report questionnaire that contains 26 items, these are subdivided into 4 QoL domains: psychological health, physical health, social relationships, environment and two other items which measure general health and overall QoL.[18]

- The Headache Impact Test-6 questionnaire (HIT-6): this questionnaire evaluates the impact of headache on the quality of life.[19]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

After appropriately diagnosing TTHs, medical professionals must then determine what the most effective treatment is for these headaches. Treatment for tension-type headache includes acute therapy for individual attacks and preventive treatment to minimise the number of attacks that occur. Acute and preventive treatment can be used together. Acute attacks of tension-type headache are usually treated with simple analgesics such as oral aspirin, paracetamol and NSAIDs. Daily preventive treatment should be considered for patients with frequent headaches or who respond poorly to abortive treatment (pain reducing treatment) alone. Amitriptyline usually in doses of 75-150 mg a day. In addition to its effects on pain, amitriptyline decreases muscle tenderness. [3]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy is the most commonly used non-pharmacologic treatment for TTH [12]. There are many different modes of treatments that can be effective, some more than others. Cervical exercises, relaxation, massage, postural exercises, cranio-cervical techniques, thermotherapy, vertebral mobilisation, and stretching are effective in reducing TTH symptoms such as pain frequency and intensity. Strength training shows a moderate effect on reducing pain[20]. Soft tissue interventions and dry needling can be used to improve pain intensity and frequency in patients with tension type headache[21]. In the studies that featured joint mobilisations, cervical range of motion showed improvements. Also, biofeedback can be used as a technique to help patients learn to control their muscle tension. [22]

Manual therapy is commonly used for TTH treatment, which consists of joint mobilisation and manipulation. A systematic review found manual therapy's effeciveness to equal prophylactic medication and tricyclic antidepressants for treating TTH[2]. There is evidence that the increased myofascial pain sensitivity in tension-type headache also could be caused by central factors (central sensitization at the level of the spinal dorsal horn/trigeminal nucleus and supraspinally)[23]. Research suggests high-velocity hands-on therapy may not be beneficial for patients with central sensitization [21]. Although manual therapy and exercises generally cause hypoalgesia, in patients with central sensitization manual therapy may induce hyperalgesia if not properly controlled. Aggressive exercise or manual therapy in early rehabilitation may worsen symptoms if excessive or forceful movements trigger sensitized peripheral nociceptors causing prolonged pain. [21][24] So, it is crucial for clinicians to accurately identify and understand patients' symptoms by frequent reassesments. Literature shows that manual therapy has been effective in improving other parameters, such as quality of life, impact and pain disability and psychological aspects thereby lowering the socioeconomic cost of the disease. [22]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- American. Physical Therapy. Association (APTA)

http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=fd8a18c8-1893-4dd3-9f00-b6e49cad5005

- World Health Organization

www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders II. Available from http://ihs-classification.org/en [last accessed 21/6/9]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Turkistani A, Shah A, Jose AM, Melo JP, Luenam K, Ananias P, Yaqub S, Mohammed L. Effectiveness of Manual Therapy and Acupuncture in Tension-Type Headache: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021 Aug 31;13(8):e17601. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17601. PMID: 34646653; PMCID: PMC8483450.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Loder E, Rizzoli P. Tension-type headache. BMJ. 2008;336(7635):88–92. doi:10.1136/bmj.39412.705868.AD

- ↑ Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Zwart JA. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007 Mar;27(3):193-210.

- ↑ Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Linde M, Steiner TJ. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. The journal of headache and pain. 2022 Dec;23(1):34.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Arnold M. Headache classification committee of the international headache society (IHS) the international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211.

- ↑ Freitag F. Managing and treating tension-type headache. Medical Clinics. 2013 Mar 1;97(2):281-92.

- ↑ Handbook of clinical neurology, ISSN: 0072-9752, Vol: 97, Issue: C, Page: 355-8

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. (2018). Cephalalgia, 38(1), 1–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202

- ↑ Schmidt-Hansen PT, Svensson P, Bendtsen L, Graven-Nielsen T, Bach FW. Increased muscle pain sensitivity in patients with tension-type headache. Pain. 2007 May 1;129(1-2):113-21.

- ↑ Paolo Martelletti, Timothy J. Steiner. Handbook of Headache: Practical Management. Springer Science & Business Media, 14 Aug 2011

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Chowdhury D. Tension type headache. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15(Suppl 1):S83–S88. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.100023

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Waldie KE, Thompson JM, Mia Y, Murphy R, Wall C, Mitchell EA. Risk factors for migraine and tension-type headache in 11 year old children. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):60. Published 2014 Sep 10. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-60

- ↑ Yang FC, Lin TY, Chen HJ, Lee JT, Lin CC, Kao CH. Increased Risk of Dementia in Patients with Tension-Type Headache: A Nationwide Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156097. Published 2016 Jun 7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156097

- ↑ Russell, M.B. Genetics of tension-type headache. J Headache Pain 8, 71–76 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-007-0366-y

- ↑ http://pennstatehershey.adam.com/content.aspx?productid=114&pid=10&gid=000011 (Accessed March 8th,2020)

- ↑ Steiner, Timothy & Gururaj, Gopalakrishna & Andrée, Colette & Katsarava, Zaza & Ayzenberg, Ilya & Yu, Shengyuan & Jumah, Mohammed & Tekle-Haimanot, Redda & Birbeck, Gretchen & Herekar, Arif & Linde, Mattias & Mbewe, Edouard & Manandhar, Kedar & Risal, ajay risal & Jensen, Rigmor & Queiroz, Luiz & Scher, Ann & Wang, Shuu-jiun & Stovner, Lars. (2014). Diagnosis, prevalence estimation and burden measurement in population surveys of headache: presenting the HARDSHIP questionnaire. The journal of headache and pain. 15. 3. 10.1186/1129-2377-15-3.

- ↑ Vahedi S. World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF): Analyses of Their Item Response Theory Properties Based on the Graded Responses Model. Iran J Psychiatry. 2010;5(4):140–153.

- ↑ Shin HE, Park JW, Kim YI, Lee KS. Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) scores for migraine patients: Their relation to disability as measured from a headache diary. J Clin Neurol. 2008;4(4):158–163. doi:10.3988/jcn.2008.4.4.158

- ↑ Varangot-Reille C, Suso-Martí L, Romero-Palau M, Suárez-Pastor P, Cuenca-Martínez F. Effects of Different Therapeutic Exercise Modalities on Migraine or Tension-Type Headache: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with a Replicability Analysis. J Pain. 2022 Jul;23(7):1099-1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2021.12.003. Epub 2021 Dec 18. PMID: 34929374.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Kamonsekia D.H, Lopesb E.P, van der Meerc H.A, and Calixtre L.B. Effectiveness of manual therapy in patients with tension-type headache - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2022:44(10):1780–1789.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Espí-López GV, Arnal-Gómez A, Arbós-Berenguer T, González ÁA, Vicente-Herrero T. Effectiveness of Physical Therapy in Patients with Tension-type Headache: Literature Review. J Jpn Phys Ther Assoc. 2014;17(1):31–38. doi:10.1298/jjpta.17.31

- ↑ Bendtsen L. Central and peripheral sensitization in tension-type headache. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2003 Nov;7:460-5.

- ↑ Courtney CA, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Bond S. Mechanisms of chronic pain–key considerations for appropriate physical therapy management. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2017 May 27;25(3):118-27.