Shoulder Examination

Original Editor - Leonid Klichinsky Top Contributors - Leonid Klichinsky, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Naomi O'Reilly, Scott A Burns, Tony Lowe, Admin, Marleen Moll, Rachael Lowe, Matt Milburn, Kai A. Sigel, George Prudden, Rucha Gadgil, Mariam Hashem, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami, Jess Bell and Rishika Babburu

Shoulder Examination[edit | edit source]

The prerequisite for any treatment in the shoulder region of a patient with pain is a precise and comprehensive picture of the signs and symptoms as they occur during the assessment and as they existed until then. Because of its many structures (most of which are in a small area), its many movements, and the many lesions that may occur either inside or outside the joints, the shoulder complex is difficult to assess. Having a systematic and structured approach to the shoulder history and examination ensures that key aspects of the condition are elicited and important conditions are not missed. Information gathered in this process can help guide decisions about the need for special tests or investigations and ongoing management.

Note, the evaluation strategies based on clinical tests and diagnostic imaging has been challenged over time, with clinical tests appearing unable to clearly identify the structures that generated pain. The interpretation of diagnostic imaging is also still controversial. [1]

Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

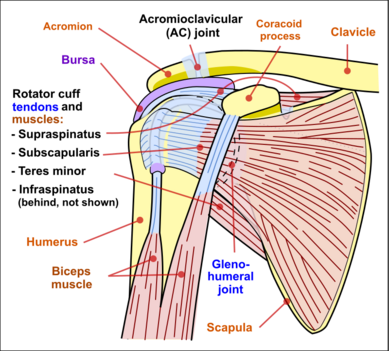

The range of motion (ROM) of the arm relative to the trunk does not just come from the glenohumeral joint. Movement also occurs in the acromioclavicular (a.c.) joint, sternoclavicular (s.c.) joint and the upper costosternal and costovertebral joints. Another prerequisite for normal movement is that the scapula should be able to move freely, relative from the dorsal thorax wall.

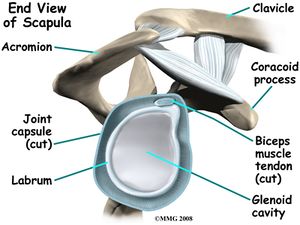

The glenohumeral joint is a multiaxial, ball-and-socket, synovial joint with a relatively shallow socket: the cavitas glenoidalis. The joint depends primarily on the muscles and ligaments for its support, stability and integrity.[2] The ring of firbocartilage labrum (glenoid labrum), surrounds and deepens the glenoid cavity of the scapula about 50%.[3]

Stability is mostly offered by the periarticular muscles, that originate from the scapula and insert on the caput humeri. This rotator cuff includes the m.supraspinatus, m. infraspinatus and m. subscapularis. The spina scapulae is a bony ridge on the dorsal side and is the insertion location of the m. trapezius and m. deltoideus. The spina scapulae broadens on the lateral side, shaping the acromion. The space between the acromion and humerus head is called the subacromial space. In this space you'll find the tendons of the rotators and the bursa subacromialis (= bursa subdeltoidea). The tuberculum minus and tuberculum majus are divided by the sulcus intertubercularis, where the tendon of the caput longum m. biceps brachii runs. This tendon continues into into the joint and has its insertion on the top ridge of the cavitas glenoidalis (labrum glenoidale).

For a full overview of shoulder anatomy, please read this page on the shoulder.

Anamnesis/Medical History[edit | edit source]

Anamnesis refers to the client's account of their past medical history. The anamnesis is a significant part of the assessment of patients with musculoskeletal dysfunction. Different anamnestic elements are collected including

- Characteristics of symptoms

- Mechanisms of pain

- Expectations, preferences and psychosocial factors of patients (yellow flags)

These elements are all weighted and included in the clinical reasoning process to guide the subsequent physical examination

Patient History[edit | edit source]

- Listen carefully to the patient’s past medical history, this may well rule out red flags and guide the shoulder examination

- History of presenting condition, how long have the complaints persisted, how did it develop, was there a trauma-moment?

- Pain distribution and severity: disturbed sleep, can de patient lie on the affected side, degree of hindrance in daily living at home and at work

- Self care and other treatments the patient has tried

- Shoulder complaints in the past: course, treatment and result of the treatment

- Relation between the complaints and work situation

- Relation between the complaints and sports activities

Try to get an impression of the location of the complaints, ask about[edit | edit source]

- The location of the pain, radiation in the arm

- Aggravating activities, e.g. difficulty with overhead activities, lifting objects, activities of daily living, sports or recreational activities

- Painful limitation when moving the upper arm in one or more directions

- Feeling of instability

- Added complaints in the neck

Questions to ask to determine possible pathologies[edit | edit source]

- Does moving your neck change your symptoms?

- Do you ever feel unstable during arm movement?

- When you do actions with your arms over your head, does this aggravate your pain level?

- Is it difficult to move your arm?

- When performing actions with your arms over your head, do your arms feel heavier?[4]

Mechanism of Injury[edit | edit source]

Asking about the mechanism of any specific injury is critical, particularly about three factors relating to the time of injury: anatomical site, limb position and subjective experiences. Take care to clarify the patient’s description of the anatomical site. A description of the arm position at the time of the injury is also valuable. For example, falling on an abducted and externally rotated arm increases the risk of shoulder dislocation or subluxation. Finally, exploring the subjective experiences of the patient at the time of injury can be useful. For example, a snapping or cracking sound may be related to a bone or ligament breaking; feeling something ‘pop out’ may suggest a joint dislocation or subluxation.

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

This video gives a 15 minute great summary of the key important procedures.

]

Clear the Cervical Spine[edit | edit source]

The cervical spine can refer pain to the shoulder/scapular region. It is imperative that the cervical spine be screened appropriately as it may be contributing to the patient’s clinical presentation.

Objective[edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

The key principle with this phase of the shoulder examination is symmetry. The shape, position and function of each shoulder should be relatively similar. Some differences can occur due to shoulder dominance; the dominant shoulder may sit lower and may appear somewhat larger due to larger muscle mass. Also look at position of scapula and or winging and any abnormal postures of swellings/injuries.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Palpation of the shoulder region may provider the physical therapist with valuable information. The physical therapist should note the presence of swelling, texture, and temperature of the tissue. Additionally the physical therapist may observe asymmetry, sensation differences, and pain reproduction. Key palpable structures include:

- Acromioclavicular Joint

- Sternoclavicular Joint

- Rotator Cuff Muscle Insertions

- Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

- Tenderness and altered sensation (subjective) local or referred

- Surface temperature, texture (objective) - a hot tense surface may indicate infection, inflammation/synovitis, recent trauma or tumour

- Swelling - may indicate effusion, tumour, nodule or bone changes

- Crepitus with movement - occurs in osteoarthritis, tendinopathy and fracture[9]

Neurologic Assessment[edit | edit source]

A comprehensive neurological examination may be warranted in patients that present with a primary complaint of shoulder pain. The presence of neurological symptoms including numbness and tingling may warrant this examination.

Myotomes[edit | edit source]

- C4 – Shoulder Elevation/Shrug

- C5 – Shoulder Abduction

- C6 – Elbow Flexion, Wrist Extension

- C7 – Elbow Extension, Wrist Flexion

- C8 – Thumb Abduction/Extension

- T1 – Finger Abduction

Dermatomes[edit | edit source]

- C4 – Top of Shoulders

- C5 – Lateral Deltoid

- C6 – Tip of Thumb

- C7 – Distal middle Finger

- C8 – Distal 5th Finger

- T1 – Medial Forearm

Pathological Reflexes[edit | edit source]

Deep Tendon Reflexes[edit | edit source]

- Biceps Brachii – C5 Nerve Root

- Brachioradialis – C6 Nerve Root

- Triceps – C7 Nerve Root

Movement Testing[edit | edit source]

The patient performs active movements in all functional planes for the shoulder. This includes flexion, extension, abduction, adduction and internal and external rotation. Estimate the range of movement or measure with a goniometer and compare the affected with the unaffected shoulder and with the normal expected range.[9][14]

Active Range of Motion (ROM)[edit | edit source]

| Active movements of the shoulder complex | ROM |

|---|---|

| Elevation through abduction | 170°-180° |

| Elevation through forward flexion | 160°-180° |

| Elevation through the plane of the scapula | 170°-180° |

| Lateral (external) rotation | 80°-90° |

| Medial (internal) rotation | 60°-100° |

| Extension | 50°-60° |

| Adduction | 50°-75° |

| Horizontal adduction/abduction (cross-flexion/ cross-extension) | 130° |

| Circumduction | 200° |

| Scapular protraction | |

| Scapular retration | |

| Combined movements (if necessary) | |

| Repetitive movements (if necessary) | |

| Sustained positions (if necessary) |

Dysfunction - affecting movements. Which movements are limited, as this can help isolate the problem.

Consider the following if movements are limited by:

- Pain: tendinopathy, impingement, sprain/strain, labral pathology

- Mechanical block: labral pathology, frozen shoulder (see MRI image to the right)

- Night pain (lying on affected shoulder): rotator cuff pathology, anterior shoulder instability, ACJ injury, neoplasm (particularly unremitting)

- Sensation of ‘clicking or clunking’: labral pathology, unstable shoulder (either anterior or multidirectional instability)

- Sensation of stiffness or instability: frozen shoulder, anterior or multidirectional instability

Passive ROM[edit | edit source]

May include each of the motions stated in the active ROM section. The therapist may opt to include overpressure to further stress the joint.

Muscle Length Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment of the flexibility of certain muscles may be warranted in patients with shoulder pain. These muscles may include, but are not limited to:

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Pectoralis Minor/Major

- Levator Scapulae

- Upper Trapezius

- Scalenes (anterior/middle/posterior)

Muscle Strength[edit | edit source]

Resistive testing of the shoulder muscles typically includes the following motions:

- Shoulder Flexion

- Shoulder Extension

- Shoulder Abduction

- Horizontal Abduction

- Horizontal Adduction

- Internal Rotation

- External Rotation

Resistive testing of the scapular stabilisation muscles may include:

- Upper trapezius

- Middle trapezius

- Lower trapezius

- Serratus Anterior

- Rhomboids

- Levator Scapulae

Joint Mobility Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment of the mobility of the joint may indicate hypomobility within the joint and/or reproduce symptoms.

- Glenohumeral

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Inferior

- Distraction

- Acromioclavicular

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Sternoclavicular

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Superior

- Inferior

- Scapulothoracic

- Elevation

- Depression

- Upward/downward rotation

- Protraction/Retraction

Special Tests[edit | edit source]

Several special tests exist for particular disorders of the shoulder. Below are links to the specific pages for each pathology that describe the special tests:

- Subacromial Related Shoulder Pain [16][17][18]

- Biceps Tendinopathy [19][20]

- Labral Tears [21][22][23]

- Laxity/Instability [24][25][26]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI)

- Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH)

- Constant-Murley Shoulder Outcome Score (CMS)

- University of Pennsylvania Shoulder Score (U-Penn)

- Visual Analogue Scale

- Patient Specific Functional Scale

Special Questions[edit | edit source]

Patients with shoulder pain should be questioned for the presence of red or yellow flags. A thorough medical history and possibly the use of a medical screening form is the initial step in the screening process. The chart below highlights some of the most common red flag conditions for patients with shoulder pain.

Red Flags[edit | edit source]

Red flags are sign and symptoms alerting the physiotherapist on a possible presence of a non-musculoskeletal, life-threatening pathology, fracture, infection, tumor and inflammatory rheumatic conditions. Examples include:[1][27]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica. Often presents as bilateral shoulder pain and weakness. These patients must be assessed for temporal arteritis

- Acute compartment syndrome. May result from significant limb swelling following an injury or an excessively tight bandage or cast. The pain is disproportionate to the injury. Pulselessness of the limb does not usually occur, or is a very late sign. This condition is a surgical emergency[9]

- Open fractures

- Fractures with nerve or vascular compromise

- Skin, but more particularly joint infections

- Neoplasia

- Serious and life threatening conditions that present with symptoms mimicking shoulder pain, such as referred ischaemic cardiac pain

- Left Shoulder- -MI 68.7% of patients reported shoulder pain during an acute myocardial infarction[28]

Yellow Flags[edit | edit source]

To assess for yellow flags, if suspected these tools may be used;

- The Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ)

- Depression Screening tools such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or the Depression Anxiety Screening Scale (DASS) are useful in screening patients for depression.

- The Pain Catastrophizing Scale, helps determine if the patient is exaggerating their pain and symptoms and the severity of the situations as a whole.

Fractures[edit | edit source]

Fractures may result from trauma such as falls onto an outstretched hand. These are known as FOOSH injuries. Commonly fractured within the shoulder region are:

- Humeral Fractures

- Clavicle Fractures[29]

- Fractures of the clavicle usually result from a direct blow to the shoulder giving axial compression. The middle 1/3 of the clavicle is most often broken with an incidence of ~80%. Distal clavicle fractures have an incidence of 10-15% and medial clavicle fractures have and incidence of 3 to 5%. Significantly displaced fractures are managed surgically. Mid-shaft clavicle fractures have a lower rate of mal-union and better functional outcomes at one year.[30] A trial of conservative management may be warranted for non-displaced clavicular fractures.

Diagnostic Imaging Radiographs of the shoulder can be used to identify cysts, sclerosis, or acromial spurs, osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joint, or calcific tendonitis. Common radiographic views may include (this may vary depending on medical provider):

- Supraspinatus Outlet View

- Scapular Y-View

- Axillary View

- Anterior-Posterior (AP) View

Clinical Picture[edit | edit source]

Presentation of different shoulder pathologies

- Patients with suspected glenohumeral instability or labral pathology may have feelings of “looseness or instability” particularly in abducted and externally rotated positions.

- Patients with suspected adhesive capsulitis may report intense global shoulder pain initially combined with a progressive loss of range of motion.

- Patients with suspected subacromial or rotator cuff related impairment may report feelings of weakness, heaviness and/or pain.

- Shoulder Osteoarthritis - progressive, activity-related pain that is deep in the joint and often localised posteriorly. As the disease progresses, night pain becomes more common

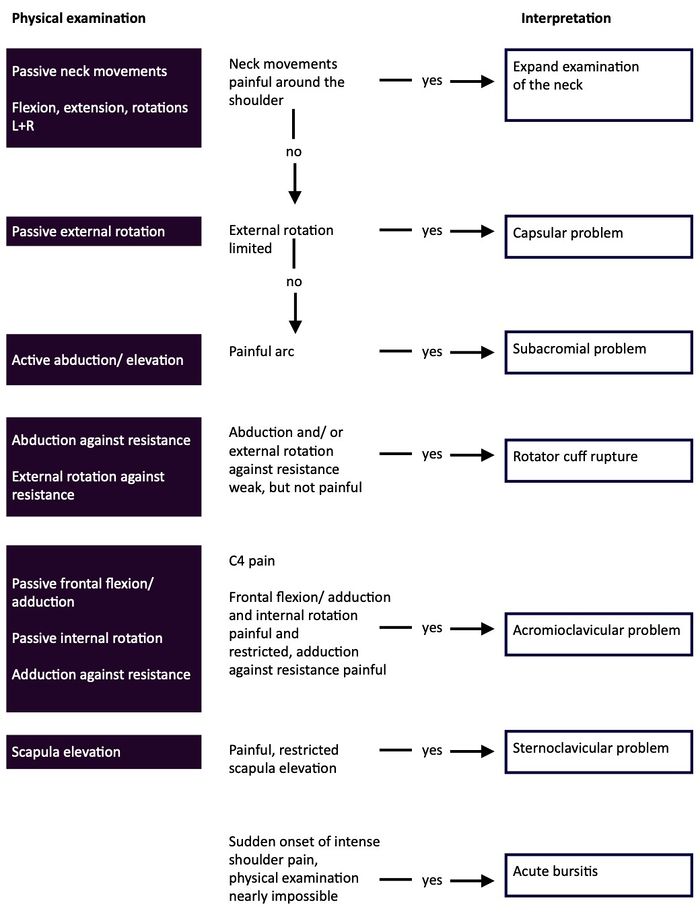

This flow diagram provides an aid to diagnosis of shoulder conditions:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ristori D, Miele S, Rossettini G, Monaldi E, Arceri D, Testa M. Towards an integrated clinical framework for patient with shoulder pain. Archives of physiotherapy. 2018 Dec;8(1):1-1. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5975572/(accessed 9.10.2022)

- ↑ Hess SA: Functional stability of the glenohumeral joint. Manual Therapy 5:63–71, 2000.

- ↑ Tillman B, Petersen W: Clinical anatomy. In Wulker N, Mansat M, Fu F, editors: Shoulder surgery: an illustrated textbook, London, 2001, Martin Dunitz.

- ↑ Flynn T, et al. Users’ guide to the musculoskeletal examination fundamentals for the evidence-based clinician. Evidence in Motion; 2008 .

- ↑ Ascension via christi Joint-by-Joint Musculoskeletal Physical Exam: Shoulder and Neck Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9kYF8K0HSs&app=desktop (last accessed 23.11.2019)

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (3 of 9): Range of motion. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7HfaAlgaro [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (4 of 9): Scapular control (Is there scapular dyskinesia?). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pEY93k5XXL0 [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (5 of 9): AC joint examination. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-y_NUVmHe-E [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 AFP Initial assessment of the injured shoulder Volume 41, No.4, April 2012 Pages 217-220 Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2012/april/initial-assessment-of-the-injured-shoulder/ (last accessed 23.11.2019)

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (6 of 9): Ruling out a SLAP tear (Kuhn's tests). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YMPZi2_Jy9o [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (7 of 9): Exam to detect a SLAP tear. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=beVd-cX_TX8 [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (8 of 9): Examination for impingement (rotator cuff). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8Rl0_KE3OA [last accessed 25/01/14]|}

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (9 of 9): Testing for instability. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fz2g5gI3RGg [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ Hislop HJ, Montgomery J. Daniels and Worthingham's Muscle Testing: Techniques of Manual Examination. Saunders 2007, 8th edition

- ↑ Magee, David J. Orthopedic physical assessment-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014.

- ↑ Calis M, et al. Diagnostic values of clinical diagnostic tests in subacromial impingement syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis, 2000 59, 44-47.

- ↑ Murphy D, Hurwitz R. A theoretical model for the development of a diagnosis-based clinical decision rule for the management of patients with spinal pain. 2007; 8: 1, 75

- ↑ Song L, Yan HB, Yang JG, Sun YH, Hu DY. Impact of patients' symptom interpretation on care-seeking behaviors of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010 Jul;123(14):1840-5

- ↑ Flynn T, et al. Users’ guide to the musculoskeletal examination fundamentals for the evidence-based clinician. Evidence in Motion; 2008

- ↑ Rutkow IM. Rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis: a critical review. Arch Surg. 1978 Jun;113(6):718-20

- ↑ Tamura M, Hoda MA, Klepetko W. Current treatment paradigms of superior sulcus tumours. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009 Oct;36(4):747-53. Epub 2009 Aug 20

- ↑ Strauss E. Flanagin BA, Mitchell MT, Thistlethwaite WA, Alverdy JC. Usefulness of liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol 2010;9 Suppl:39-42.

- ↑ Diagnosis and treatment of atypical presentations of hiatal hernia following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010 Mar;20(3):386-92. Epub 2009 Oct 24.

- ↑ McKee MD. Clavicle fractures in 2010: sling/swathe or open reduction and internal fixation? Orthop Clin North Am. 2010 Apr;41(2):225-31

- ↑ Altamimi SA, McKee MD. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Mar;90 Suppl 2 Pt 1:1-8

- ↑ BJSM Videos. Shoulder Exam (2 of 9): Inspection and Palpation. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xf52jbNA7wg [last accessed 25/01/14]

- ↑ Murphy D, Hurwitz R. A theoretical model for the development of a diagnosis-based clinical decision rule for the management of patients with spinal pain. 2007; 8: 1, 75 .

- ↑ Osman A et al. The Pain Catastophizing Scale:Further Psychometric Evaluation with Adult Samples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000; Vol.23(4): 351-365.

- ↑ McKee MD. Clavicle fractures in 2010: sling/swathe or open reduction and internal fixation? Orthop Clin North Am. 2010 Apr;41(2):225-31

- ↑ Altamimi SA, McKee MD. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Mar;90 Suppl 2 Pt 1:1-8