Prostate Cancer

Original Editors - Students from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Taylor Carta, Devin Conway, Shaimaa Eldib, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Tony Lowe, Evan Thomas, Vidya Acharya, Nicole Sandhu, Jess Bell, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Elaine Lonnemann, Mandy Roscher, 127.0.0.1, Rosie Swift, Tarina van der Stockt, Venugopal Pawar and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

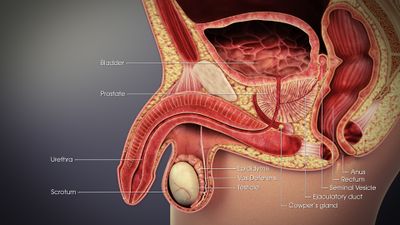

Prostate cancer affects the prostate gland, which is part of the reproductive system and functions to create seminal fluid.[1] Prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in men after skin cancer and is the second leading cancer-related cause of death in men.

- It is slow-growing and affects one-third of all males by the age of 50[2]

- Commonly metastasizes, primarily spreading to bone, which frequently causes lumbar pain[2]

- Even with such a fairly high mortality and metastasis rate, the microscopic changes that occur in the prostate can be slow-growing and may never cause health issues and often cause no signs or symptoms[2]

- Variations in the rate of prostate cancer progression and spreading suggest genetic involvement along with familial predisposition and diet[2]

Overall

- Prostate cancer has become a significant issue due to the fact that it has become so prevalent.

- Approximately 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer globally.

- More men are being diagnosed due to an increase in routine screenings

- More men are living longer with the disease due to advancements in treatment.[2]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed organ cancer in men and the second leading cause of male cancer death in the United States. Lung cancer is first.[3]

- Relatively few patients with prostate cancer die of the disease although this still amounts to over 26,000 deaths per year in the United States. It is projected that rates of prostate cancer will continue to increase through to 2025, particularly in men aged over 69 years[4]

- Prostate cancer occurs more commonly in the developed world

- The overall 5-year survival rate is 99% in the United States

- Incidence rates have been increasing although the death rate has been decreasing since 1992 when PSA testing became widely available

- Ninety-nine percent of all prostate cancers occur in those over the age of 50, but when it occurs in younger men, it can be quite aggressive

- In the United States, prostate cancer is more common in African Americans by more than double the rate in the general population

- It is less common in men of Asian and Hispanic descent than in Whites

- In Europe, prostate cancer is the third most diagnosed cancer after breast and colorectal.

- In the United Kingdom, it is the second most common cause of male cancer death after lung cancer, similar to the situation in the United States

- More than 80% of men will develop prostate cancer by age 80. However, in this age group, it will probably be slow growing, lower grade, relatively harmless and have little impact on their survival

- According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), every American man has a lifetime risk of 11.6% of developing clinically significant prostate cancer (Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 or higher)[3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical Signs and Symptoms[2][5][6] (also may be present with other prostate-related disease processes such as Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) or Prostatitis).[5]

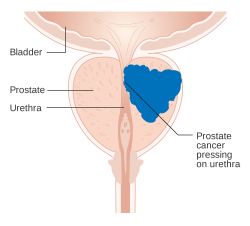

- Urinary retention or other urinary complaints

- Low back pain, inner thigh or perineal pain or stiffness

- Hematuria

- Blood in semen

- Suprapubic or pelvic pain/discomfort

- Sexual dysfunction

- Early prostate cancer may be asymptomatic. Routine screenings of prostate cancer are commonly being done on asymptomatic men.

Manifestations of Metastasized Prostate Cancer[2][5]:

- Sciatica

- Bone pain and lower extremity pain

- Lymphedema of the groin or lower extremities

- Neurological changes from spinal cord compression

- Anaemia

- Weight loss and loss of appetite

Associated signs and symptoms to ask the patient about include:

- Melena

- Sudden moderate to high fever

- Chills

- Changes in bowel or bladder function

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

A retrospective study by Chamie et al. titled “Comorbidities, Treatment and Ensuing Survival in Men with Prostate Cancer” looked at men diagnosed with prostate cancer and how comorbidities affected their mortality and treatment.[7]

Survival differences corresponding to 5-year and 10-year survival rates were studied. “The respective 5-year and 10-year survival for those without any comorbid conditions were 88% and 75%; men with moderate-severe COPD were 50% and 12%; diabetes with end-organ damage were 57% and 36%.” So, just based off of this single study conducted it can be speculated that comorbidities such as COPD and diabetes could factor into the mortality of those diagnosed with prostate cancer.[7]

A study by Matthes and colleagues from 2018 examined the association between comorbidities with the treatment of prostate cancer and prostate cancer-specific mortality in Switzerland.[8] They found that the age of a patient is a stronger predictor of treatment choices than comorbidities, but comorbidities have a greater impact on mortality.[8]

Some studies have also shown that there is a lower risk of getting a less dangerous form of prostate cancer and an increased risk of getting a more advanced form of it in obese men. Other studies have found that obesity may create a greater risk of dying from prostate cancer.[9]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Screening test[edit | edit source]

Prostate-specific Antigen (PSA) Test:

- A blood test used to test for elevated levels of PSA, which occurs with any changes in the prostate.

- The risk of disease increases as the PSA level increases; however, a normal level of PSA has not been determined[2].

- If prostate cancer develops the PSA levels will typically increase past 4 ng/mL of blood, according to the American Cancer Society.

-PSA level between 4 and 10: 25% chance of having prostate cancer

-PSA greater than 10: over 50% chance of having prostate cancer

- No PSA level guarantees the absence of prostate cancer[5].

-Approximately 15% of men with a PSA below 4 will be positive for prostate cancer when biopsied3

- There are several factors that may increase PSA levels[9]

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force[10] recommends against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer due to the test often producing false positives, which can then lead to harmful side effects from proceeding diagnostic tests or treatment[5]. This recommendation is considered controversial and is currently in the process of being updated according to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force website.[10]

Digital Rectal Examination (DRE)[edit | edit source]

- A DRE is an exam in which the doctor inserts a finger into the rectum to allow the ability to palpate the back of the prostate gland, which allows for the ability to feel possible cancers or bumps[9]

- There is a lack of evidence to support the efficacy of DRE.[11] The majority of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer have abnormal PSA levels, but normal DRE results[5]

- This test may still be included in screening because even though it is less effective than a PSA blood test overall it may still be able to detect cancer in men that may demonstrate normal PSA levels

Prostate cancer often grows slowly; therefore, men without symptoms of prostate cancer who do not have a 10-year life expectancy may not be screened. Overall health status, not just age, is important when making decisions, and patients should talk to their healthcare provider about the pros and cons of being tested and treated for prostate cancer. [9][12]

The recommended age to start screening for prostate cancer according to the American Cancer Society[9]:

- 50 years of age for men with an average risk, and who have at least a 10-year life expectancy

- 40-45 years of age for African American men and those with a first-degree relative diagnosed with prostate cancer before 65 years old

- 40 years of age for men with several first-degree relatives who had prostate cancer at an early age

Biopsy[edit | edit source]

- The diagnosis of prostate cancer is established via a biopsy of the prostate gland and may be indicated for individuals who have elevated PSA levels.[5]

- A small piece of the prostate gland is removed and examined under a microscope for cancer cells. If cancer cells are found then a Gleason score will be determined from the biopsy.

- A Gleason score indicates how likely the cancer is to spread. It ranges from 2–10, the lower the score the less likely it is that cancer will spread[12]

- False-negative results often occur; therefore, multiple biopsies may be done before prostate cancer can be detected and confirmed[5][12][9]

- A small probe is inserted into the rectum and uses sound waves (ultrasound) to create a picture of the prostate.

- TRUS is not utilized as a screening tool because it cannot always differentiate between normal tissue and cancerous tissue. Instead, it is often used in conjunction when a prostate biopsy to help guide the biopsy needles into the right area of the prostate.

- TRUS can also be utilized to determine the PSA density and to tell which treatment choices are appropriate.[9]

Staging[2]:[edit | edit source]

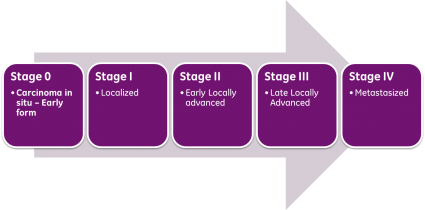

Stage I: Cancer cannot be felt during a DRE, but it may be found during surgery being done for another reason. Cancer has not yet spread to other areas.

Stage II: Cancer can be felt during a DRE or discovered during a biopsy. Cancer has not yet spread.

Stage III: Cancer has spread to nearby tissue

Stage IV: Cancer has spread to lymph nodes or to other parts of the body [13]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The cause of prostate cancer is not yet known; however, there are several known risk factors that have been shown to indicate an increase in the risk of developing this type of cancer.[9]

Non Modifiable Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Advancing Age[edit | edit source]

- Most men who acquire prostate cancer are 65 years or older.

- It is very rare to develop prostate cancer before 45 years of age.

Race/Ethnicity[edit | edit source]

- African-American men have an increased risk of developing prostate cancer compared to white or Hispanic men, and the risk is less in men of Asian and Native American descent.[2]

- The mortality rates in African-American men are more than twice as high as in any other racial group.[5]

Geography[edit | edit source]

- Prostate cancer occurs more frequently in North America, northwestern Europe, Australia, and on the Caribbean islands, and it is less common in Asia, Africa, Central America, and South America.[9]

Family History[edit | edit source]

- There is an increased risk of developing prostate cancer if a brother or father had the disease, and the risk increases the more first degree relatives that have been affected.[2]

Gene Mutations[9][edit | edit source]

Viruses[edit | edit source]

Hormones[edit | edit source]

- A study performed showed a possible correlation between elevated levels of luteinizing hormone and of testosterone: dihydrotestosterone and a mild increase in the risk of prostate cancer[5]

Modifiable Risk Factors[2][9][edit | edit source]

Diet[edit | edit source]

- A diet high in animal fat, red meat, and high-fat dairy products may be attributed to an increased risk in developing prostate cancer.

Occupational exposures[edit | edit source]

- Such as chemicals (herbicides, pesticides, and toxic combustible products), cadmium, and other metals

Multiple sex partners[edit | edit source]

Low levels of vitamins or selenium[edit | edit source]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Early prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and is often diagnosed because men seek medical attention for issues regarding urinary dysfunction (i.e. retention) or low back, hip, or leg pain. Prostate cancer almost exclusively metastasizes to the bone of the pelvis, spine, or femur via the bloodstream or lymphatic system and spreads in the early stages. It has also been known to spread to the bladder, rectum, and distant organs such as the liver, lung,

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The first decision in managing prostate cancer is determining whether any treatment at all is needed. Prostate cancer, especially low-grade tumors, often grow so slowly that frequently no treatment is required; particularly in elderly patients and those with comorbidities that would reasonably limit life expectancy to 10 additional years or less[3].

Note: The interprofessional team can optimize the treatment of these patients through communication and coordination of care. Primary care providers, urologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and nurse practitioners provide diagnoses and care plans. The interprofessional team can improve outcomes for patients with prostate cancer.

Active Surveillance - Many low-risk cases can now be followed with active surveillance. Under active surveillance, patients are usually required to have regular, periodic PSA testing and at least one additional biopsy 12 to 18 months after the original diagnosis[3].

Localized prostate cancer[9][5][12][edit | edit source]

In localized disease, it should be understood that for the majority of patients, treatment selection makes very little difference in overall survival for at least the next 10 years. Therefore, definitive therapy should only be offered to those patients who are reasonably expected to live another ten years or longer based on age and co-morbidities[3].

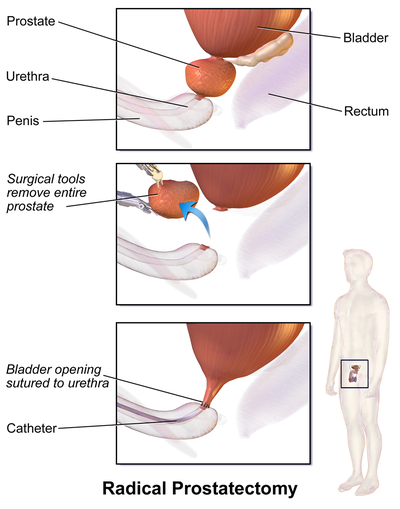

Definitive treatment of localized disease now includes radiation therapy (external beam and/or brachytherapy radioactive seed placement), radical prostatectomy and cryotherapy (usually reserved for radiation therapy failures). Radiation therapy tends to have much fewer side effects (about 50% less) than radical prostatectomy surgery with very similar overall survival.

- Most patients with potentially curable, localized disease, good performance status, reasonably good quality of life and greater than 10-year life expectancy, the choice of treatment should be an informed patient decision made after discussions including both urology (surgery) and radiation therapy.

- Definitive therapy can have significant side effects such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence, discussions often focus on balancing the goals of therapy (possible cancer cure, the potential for increased survival, psychologically "getting rid" of the cancer) with the risks of lifestyle alterations (treatment side effects, complications, cost, possible lack of ultimate survival benefit and questionable quality of life improvement over doing nothing)[3].

Definitive Treatments include:

Prostatectomy: [edit | edit source]

- This involves the removal of the prostate gland. A radical prostatectomy is the removal of the prostate gland and some surrounding tissue[14].

Radiation therapy: [edit | edit source]

- Use of high-energy radiation to try to kill the cancer cells.1. External beam radiation therapy: the radiation is directed into the cancer cells from the outside of the body 2.Brachytherapy (Internal radiation therapy): Radioactive pellets surgically implanted into the cancerous area to try to kill the cells from the inside of the body

Hormone therapy:[edit | edit source]

- Aims to block the cancer cells from obtaining the essential hormones needed to grow.

Cryotherapy:[edit | edit source]

- Treatment includes placing a probe near the cancer cells to try to kill them by freezing them.

Chemotherapy: [edit | edit source]

- Use of drugs (oral or intravenous) to try to kill or reduce in size the cancer cells.

Vaccine treatment: [edit | edit source]

- Cancer vaccine made specifically for each man that works to boost the body’s immune system to kill prostate cancer cells. This is mainly used for advanced cancers that are not responding to hormone therapy.

Metastatic prostate cancer[9][edit | edit source]

Rarely can prostate cancer that has metastasized be cured. Management of these patients usually includes such treatments as:

- Preventing and treating cancer spread to bones via medications (i.e. Biphosphonates, Denosumab, etc.)

- Relief of particular symptoms (i.e. relieving bone pain via pain medication)

- Trying to slow further progression of the disease

Medications[edit | edit source]

There are many medications that can be used in the treatment of prostate cancer. Pharmacotherapy is used in the treatment of prostate cancer in hopes to induce remission, reduce morbidity and reduce complications.[5] A list of FDA approved drugs for the treatment of prostate cancer can be found at the National Cancer Institute: http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/prostate.

Some of the more common medications used for prostate cancer include[5]

- Hormone Therapy: used to stop the production of testosterone or to block uptake of testosterone by cancer cells[15]

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists: causes medical castration which reduces production of testosterone Androgen antagonists: inhibits interaction with testosterone

2. Bisphosphonates: used in men with castrate-resistant cancer and with bone metastases eg Zoledronic acid

3. Antifungal agents: works similar to antiandrogens and are used when antiandrogens fail eg Ketoconazole

4. Chemotherapeutic agents

5. Corticosteroids: modifies the body's immune response eg Prednisone, Hydrocortisone, Dexamethasone

I6. Immunologic agents: stimulates patient's own immune system eg Provenge

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The most common impairments found with genitourinary cancer include

- Strength (88.2%) i.e. deconditioning

- Incontinence (81.7%) and urgency - one of the most common side effects of prostate cancer treatment.[17]

- Genitourinary dysfunction ( eg.erectile dysfunction).[18]

- Pain (25.5%)

- Fatigue

- Peripheral Neuropathy

- Lymphedema[17]

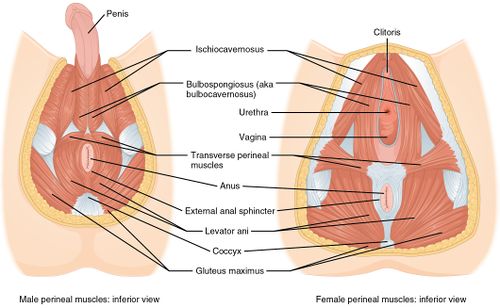

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT)[edit | edit source]

The mainstay of conservative treatment

- Improve urinary control by increasing the strength, endurance, and coordination of the pelvic floor muscles.[19]

- Pilates and pelvic floor muscle training (with electrical stimulation) improve urinary incontinence post-prostatectomy.[19] (the results for the effectiveness of PFTM for incontinence are not conclusive for its long term effects).

- A systematic and meta-analysis examining the effect of preoperative PFMT on postoperative urinary incontinence following radical prostatectomy found that preoperative PFMT improves postoperative urinary incontinence at 3 months but not at 6 months, suggesting it improves early continence but not long-term continence rates.[20]

Biofeedback training[edit | edit source]

Erectile dysfunction has a negative effect on the quality of life of men and their sexual partners.

- The main cause of erectile dysfunction after a radical prostatectomy is neurogenic, because of intraoperative injury to the neurovascular bundle.[21]

- A prospective, randomized, controlled trial conducted by Prota et al. compared early postoperative biofeedback pelvic-floor biofeedback training (PFBT) to usual care and found early PFBT appears to have a significant impact on the recovery of erectile dysfunction.[22] Other studies have found similar results.[23][24][25][26]

- Physical therapists working with individuals post-prostate cancer treatment or individuals with a history of prostate cancer should always screen for genitourinary dysfunction as incontinence and erectile dysfunction may remain for a period of time after cancer treatment. The physical therapist should treat or refer appropriately.[17]

The method used by Prota et al. is as follows:[22]

- an electromyographic apparatus was used, a surface electrode (3M, Sumare, Brazil) was inserted into the anus and the reference electrode was placed on the left lateral malleolus

- the patients practised 3 series of 10 rapid contractions while lying on their right side and viewing a computer monitor to improve the phasic musculature component

- then patients practised 3 sustained contractions of 5, 7 or 10 s depending on ability to maintain the contraction of pelvic-floor muscle tonic component

- patients were then placed in the supine position, with hips flexed to approximately 60 °, to practice 10 contractions during prolonged expiration, avoiding the Valsalva manoeuver

- Verbal and written instructions were used to conduct daily home exercises while lying, sitting and standing

Additional treatment[edit | edit source]

- It is important to treat the patient as a whole, which includes targeted aerobic training and strengthening exercises for prevention and management of cancer-related fatigue exhibits efficacy when used during and after treatment in various types of cancer according to some studies.[17]

Differential Diagnosis[2][5][edit | edit source]

- Obstruction of lower urinary tract

- Prostatitis

- Prostatic abscess

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- Tuberculosis of Genitourinary System

- Musculoskeletal: Low back, hip, or leg pain

- Bony metastases of prostate cancer are often blastic as found by radiologic imaging, they can cause lytic lesions which may mimic Paget's disease.[5]

- Any sudden neurologic changes of the lower extremities such as weakness in older men with a history of prostate cancer should raise awareness of possible spinal cord compression.[5]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

1. Glode, LM. Case Reports on Prostate Cancer. Reviews in Urology 2004;6(Suppl 7):S39-S45. Published 2004. Available from: PMC.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1472886/

2. Kubicka-Wolkowska J, Debska-Szmich S, Lisik-Habib M, Noweta M, Potemski P. Malignan acanthosis nigricans associated with prostate cancer: a case report. BMC Urology. 2014;14:88. Published November 2014. Available from: PMC http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25399333

3. Bourlon M, Glode L, Crawford E. Base of the Skull Metastases in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Oncology Journal. December 2014. Available from: Cancer network. http://www.cancernetwork.com/oncology-journal/base-skull-metastases-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer

4. Aksoy S, Orhan K, Kursun S, Eray Kolsuz M, Celikten B. Metastasis of prostate carcinoma in the mandible manifesting as numb chin syndrome. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2014;12:401. Published December 2014. Available from: PMC. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4326431/

Resources[edit | edit source]

American Cancer Society

Toll-free number: 1-800-227-2345

Website: www.cancer.org

Prostate Cancer Foundation (formerly CaPCURE)

Toll-free number: 1-800-757-2873 (1-800-757-CURE) or 1-310-570-4700

Website: www.pcf.org

US Too International, Inc.

Toll-free number: 1-800-808-7866 (1-800-80-US-TOO)

Website: www.ustoo.com

Urology Care Foundation

Toll-free number: 1-800-828-7866

Website: www.urologyhealth.org

National Association for Continence

Toll-free number: 1-800-252-3337 (1-800-BLADDER)

Website: www.nafc.org

National Cancer Institute

Toll-free number: 1-800-422-6237 (1-800-4-CANCER); TYY: 1-800-332-8615

Website: www.cancer.gov

National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship

Toll-free number: 1-888-650-9127

Website: www.canceradvocacy.org

To get more information, visit the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Prostate Cancer Treatment Option Overview, which a site that can help to find a healthcare provider or treatment site that cares for cancer. Also, go to Facing Forward: Life After Cancer Treatment for more information about treatment and can help help assist with various treatment sources.[9]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ WebMD. What Is the Prostate? http://www.webmd.com/men/what-is-the-prostate (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Goodman C, Synder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists Screening for Referral. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Saunders 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Stephen W. Leslie; Taylor L. Soon-Sutton; Hussain Sajjad; Larry E. Siref. Prostate Cancer Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550/#:~:text=Pathophysiology,-The%20prostate%20is&text=Prostate%20cancer%20is%20an%20adenocarcinoma,tissue%20forming%20a%20tumor%20nodule. (last accessed 8.6.2020)

- ↑ Kelly SP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Cook MB. Past, Current, and Future Incidence Rates and Burden of Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the United States. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4(1):121-7.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 Medscape. Prostate Cancer. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1967731-overview (accessed 9 April 2016)

- ↑ Wikipedia. Prostate Cancer. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostate_cancer# (accessed 10 April 2016).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chamie K, Daskivich TJ, Kwan L, Labo J, Dash A, Greenfield S, Litwin MS. Comorbidities, treatment and ensuing survival in men with prostate cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2012 May;27(5):492-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Matthes KL, Limam M, Pestoni G, Held L, Korol D, Rohrmann S. Impact of comorbidities at diagnosis on prostate cancer treatment and survival. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(4):707-15.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 American Cancer Society. Prostate Cancer. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/index (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate Cancer: Screening. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening?ds=1&s=prostate%20cancer (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ↑ Naji L, Randhawa H, Sohani Z, Dennis B, Lautenbach D, Kavanagh O et al. Digital Rectal Examination for Prostate Cancer Screening in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(2):149-54.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prostate Cancer. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/index.htm (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ↑ Wikipedia. Cancer staging. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancer_staging (accessed 10 April 2016).

- ↑ Wikipedia. Prostatectomy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostatectomy (accessed 10 April 2016).

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Conditions Prostate Cancer. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prostate-cancer/multimedia/prostate-cancer/img-20006744 (accessed 9 April 2016)

- ↑ OsmosisProstate cancer Available fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8sC3s9Jek7U&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Alappattu MJ, Coronado RA, Lee D, Bour B, George SZ. Clinical characteristics of patients with cancer referred for outpatient physical therapy. Physical Therapy 2015 April;95(4):526-38.

- ↑ American Cancer Society. Surgery for prostate cancer. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/surgery.html

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gomes CS, Pedriali FR, Urbano MR, Moreira EH, Averbeck MA, Almeida SH. The effects of Pilates method on pelvic floor muscle strength in patients with post‐prostatectomy urinary incontinence: A randomized clinical trial. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2018 Jan;37(1):346-53.

- ↑ Chang JI, Lam V, Patel MI. Preoperative pelvic floor muscle exercise and postprostatectomy incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European urology. 2016 Mar 1;69(3):460-7.

- ↑ Dubbelman YD, Dohle GR, Schröder FH. Sexual function before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a systematic review of prognostic indicators for a successful outcome. European urology. 2006 Oct 1;50(4):711-20.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Prota C, Gomes CM, Ribeiro LH, de Bessa Jr J, Nakano E, Dall'Oglio M, Bruschini H, Srougi M. Early postoperative pelvic-floor biofeedback improves erectile function in men undergoing radical prostatectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. International journal of impotence research. 2012 Sep;24(5):174.

- ↑ Sighinolfi MC, Rivalta M, Mofferdin A, Micali S, De Stefani S, Bianchi G. Potential effectiveness of pelvic floor rehabilitation treatment for postradical prostatectomy incontinence, climacturia, and erectile dysfunction: a case series. The journal of sexual medicine. 2009 Dec;6(12):3496-9.

- ↑ Van Kampen M, De Weerdt W, Claes H, Feys H, De Maeyer M, Van Poppel H. Treatment of erectile dysfunction by perineal exercise, electromyographic biofeedback, and electrical stimulation. Physical therapy. 2003 Jun 1;83(6):536-43.

- ↑ Lin YH, Yu TJ, Lin VC, Wang HP, Lu K. Effects of early pelvic-floor muscle exercise for sexual dysfunction in radical prostatectomy recipients. Cancer nursing. 2012 Mar 1;35(2):106-14.

- ↑ Dorey G, Speakman M, Feneley R, Swinkels A, Dunn C, Ewings P. Randomised controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle exercises and manometric biofeedback for erectile dysfunction. Br J Gen Pract. 2004 Nov 1;54(508):819-25.