Lumbar Vertebrae

Original Editors - Naomi O'Reilly

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Admin, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Scott Buxton, George Prudden, Joao Costa and Rachael Lowe

General Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Vertebral Bodies[edit | edit source]

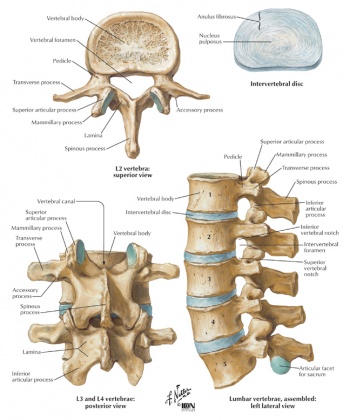

The Lumbar Vertebrae are larger and heavier than vertebral bodies in other regions. The lumbar vertebral body is kidney-shaped when viewed superiorly, so it is wider from side to side than from front to back, and a little thicker in front than in back with a thin cortical shell which surrounds cancellous bone. The posterior aspect of the vertebral body changes from slightly concave to slightly convex from L1 - L5 with an increasing diameter due to the increased load carried at each body.[1][2]

The main weight of the body is carried by the vertebral bodies and disks. The lamina, facets and spinous process are major parts of the posterior elements that help guide the movement of the vertebrae and protect the spinal cord.

Vertebral Foramen[edit | edit source]

The vertebral foramen is triangular in shape and is larger than in the thoracic vertebrae but smaller than in the cervical vertebrae.

Bony Structures[edit | edit source]

Pedicles[edit | edit source]

The pedicles originate posteriorly and attach to the cranial half of the body forming the vertebral arch with the laminae. The pedicles become shorter and broader becoming more lateral from L1 - L5 which narrows the anteroposterior diameter and widens the transverse diameter of the vertebral canal.

Laminae[edit | edit source]

Forming the Vertebral Arch with the Pedicles, each laminae is flat and broad blending in centrally with the spinous process.

Spinous Processes[edit | edit source]

The spinous processes are short and sturdy in the Lumbar Vertebrae, often described as "Hatchet-Shaped".

Transverse Processes[edit | edit source]

The transverse process is long and slender in the Lumbar Vertebrae with accessory processes on the posterior surface at the base of each process.

Articular Processes[edit | edit source]

The superior articular facets are directed posteromedially or medially while the inferior articular facets are directed anterolaterally or laterally with a mamillary process on posterior surface of each superior articular process.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Vertebral Causes of Spinal Pain:[4]

- Developmental:Spondylolisthesis, Scoliosis, Hypermobility, Various uncommon disorders.

- Degenerative: Disc lesions without root compression, Disc lesions with root compression, Disc lesions with compression of spinal cord or cauda equina, Osteoarthrosis of the apophyseal joint, Hyperostosis, Instability.

- Trauma: Fracture, Stress fracture, Subluxation, Ligamentous injury.

- Tumour: Secondary carcinoma, Myelomatosis.

- Infection: Staphylococcal, Tuberculous, E.coli, Brucella melitensis.

- Inflammatory Arthropathy: Ankylosing spondylitis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Reiter´s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn´s disease, Psoriasis.

- Metabolic: Osteoporosis, Osteomalacia

- Unknown: Paget´s Disease

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

Sequence proposed by Maitland for the physical examination of the intervertebral segment:[4]

- Active Tests

- Active movements: in standing, except for rotation which is best tested in sitting.

- Auxiliary tests associated with active movements tests.

- Isometric tests in the lumbar area produces considerable intervertebral movement. It may be necessary to test the muscle isometrically in different positions of the joint range and to compare the degree of pain produced by an active resisted movement with that of a passive movement.

- Passive Tests

- Movement of the pain-sensitive structures in the vertebral canal and intervertebral foramen.

- Palpation: The positions of the vertebrae should be assessed in relation to adjacent vertebrae. Palpation of the spinous process posteriorly and laterally is useful both in regard to the position of the vertebra and to the state of the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments. No too much importance should be placed on abnormalities found on this assessment, only relevant if they are verified by radiology.

- Passive range or intervertebral movement.

Computed Tomography (CT)[edit | edit source]

In a study which compares radiography with CT, low dose CT scored better than radiography on the following: sharp reproduction of disc profile and vertebral end-plates, intervertebral foramina and pedicles, intervertebral joints, spinous and transverse processes, sacro-iliac joints, reproduction of the adjacent soft tissues, and absence of any obscuring superimposed gastrointestinal gas and contents. The reviewers visualised disk degeneration, spondylosis/diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and intervertebral joint osteoarthritis more clearly and were more certain with low dose CT. [5]

Radiography[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spine radiography is often performed instead of CT for radiation dose concerns. In a study which compares radiography with CT, radiography scored better on sharp reproduction of cortical and trabecular bone.[5] Other studies showed that radiography is likely to be cost-effective only when satisfaction is valued relatively highly. Therefore, strategies to enhance satisfaction for patients with low back pain without using lumbar radiography should be pursued.[6]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)[edit | edit source]

Conceptual links between MRI findings and spine-related symptoms. Primary MRI predictors of interest on italic.[8]

- MRI findings linked to Low Back Pain:

- Vertebrae Endplate Changes

- Annular Fissures

- Facet Osteoarthritis

- Disc Dessication

- Disc Height Narrowing

- Disc Bulging

- MRI Findings Linked to Radicular Symptoms

- Central canal stenosis

- Disc extrusions

- Nerve root impingement

- MRI Findings Linked to Both

- Spondylolisthesis

- Disc protrusions

MRI for low back pain is of little value in making a diagnosis based on specific spinal pathoanatomic changes. With respect to chronic low back pain or radicular symptoms, MRI findings does not explain the vast majority of incident symptom cases.[8]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Invasive Treatment[edit | edit source]

- Percutaneous Vertebroplasty: percutaneous intraosseous methylmethacrylate cement injection to treat osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures and spinal column neoplasms.[10]

- Kyphoplasty: Kyphoplasty is a type of vertebral augmentation for compression fractures.[11]

- Lumbar Fusion: The goal of a lumbar fusion is to stop the pain at a painful motion segment in the lower back. Most commonly, this type of surgery is performed for pain and disability caused by lumbar degenerative disc disease or a spondylolisthesis.[11]

There are also many surgical approaches to performing spinal fusion, such as Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion(ALIF), Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion(PLIF), eXtreme Lateral Interbody Fusion(XLIF), Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion(TLIF), posterolateral gutter fusion, anterior/posterior fusion, and certain minimally invasive approaches. [11]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

- Traction: Large forces are not required to separate the vertebrae. Vertebral separation could provide relief from radicular symptoms by removing direct pressure or contact forces from sensitised neural tissue. [12]

- Manual Mobilisation: Physiotherapists use manual mobilisation for different pathologies of the lumbar spine. Good knowledge of the appropriate technique is needed as well as take into account some contraindications, for example, high velocity spinal manipulation techniques are contraindicated in individuals with osteoporosis.

- Therapeutic Exercise: Exercise interventions, alone or in combination with other treatments, have a positive effect on diverse pathologies, for example, low-back pain due to spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.[13]Exercise interventions can be considered as well as preventive treatment because it has positive effects on bone mineral density, and exercise programs can prevent fractures due to falls. [14]

- Postural Taping uses tape applied to the skin to provide increased proprioceptive feedback about postural alignment, improve thoracic extension, reduce pain and facilitate postural muscle activity and balance.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Moore KL, Agur AM; Dalley AF. Essential Clinical Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams; Wilkins, 2011.

- ↑ Ombregt, L. Applied Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. Chapter 31 In: A System of Orthopaedic Medicine. Elsevier, 2013.

- ↑ Kenhub - Learn Human Anatomy. Lumbar Spine Anatomy and Function - Human Anatomy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VEPp4od4RjY [last accessed 12/04/2023]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 G.D. Maitland. Vertebral Manipulation. Fourth Edition. London-Boston: Butterworths, 1977.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Alshamari M, Geijer M, Norrman E, Lidén M, Krauss W, Wilamowski F, Geijer H. Low dose CT of the lumbar spine compared with radiography: a study on image quality with implications for clinical practice. Acta Radiologica. 2016 May;57(5):602-11.

- ↑ Miller P, Kendrick D, Bentley E, Fielding K. Cost-effectiveness of lumbar spine radiography in primary care patients with low back pain. Spine. 2002 Oct 15;27(20):2291-7.

- ↑ Dr Jamie Motley. Lumbar Spine Radiology Tutorial. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AhDELuXS3LM [last accessed 12/04/2023]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Suri P, Boyko EJ, Goldberg J, Forsberg CW, Jarvik JG. Longitudinal associations between incident lumbar spine MRI findings and chronic low back pain or radicular symptoms: retrospective analysis of data from the longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBACK). BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2014 Dec;15:1-0.

- ↑ Donald Corenman, MD, DC. How to Read a MRI of the Normal Lumbar Spine | Lower-Back | Vail Spine Specialist. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PZqimf1DbcE [last accessed 12/4/2023]

- ↑ Barr JD, Barr MS, Lemley TJ, McCann RM. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for pain relief and spinal stabilization. Spine. 2000 Apr 15;25(8):923-8.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Spine Health. Description of Kyphoplasty Surgery. http://www.spine-health.com/treatment/back-surgery/description-kyphoplasty-surgery. Acessed: 2017/04/14

- ↑ Krause M, Refshauge KM, Dessen M, Boland R. Lumbar spine traction: evaluation of effects and recommended application for treatment. Manual Therapy 2000; 5:72-81.

- ↑ McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Manual therapy. 2003 May 1;8(2):80-91.

- ↑ Li WC, Chen YC, Yang RS, Tsauo JY. Effects of exercise programmes on quality of life in osteoporotic and osteopenic postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation. 2009 Oct;23(10):888-96.