Cluster Headache Case Study

Patient Background[edit | edit source]

- 49 year old male

- Working as a construction manager for the past 20 years

- Has had intermittent low back pain for as long as he can remember

- Other co-morbidities include hypertension and diabetes type II, both of which are controlled with medication

- Patient has received previous outpatient care for his low back pain and describes that he had a decrease in pain for a period of time before the pain returned in his low back.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Subjective[edit | edit source]

The patient is a 40 year old African American male. The patient reports to physical therapy for a work-hardening evaluation that a company has requested in order to clear him for heavy labor. Half way through the lifting evaluation, the patient immediately stops in the middle of the timed trial and sits down against the wall. When the therapist attends to the patient, he reports that he has been experiencing these “headache attacks” for the past month around this time of day. The patient is moved to a private treatment room with the lights off so that he may lie down and rest; however, he instead paces back and forth around the room. Once the patient is stable, the therapist begins to interview the patient on the nature of these headaches. The patient reports that since he started working late night shifts at the construction company one month ago, he was forced to nap throughout the afternoon in order to be safe to work in the early hours of the morning. However, when he would wake up he would experience excruciating, burning pain above and behind his left eye. The pain was so severe that he could “feel something pulsating on the side of my head.” Once the pain subsided 20-30 minutes later, the patient looked in the mirror and saw that his left eyelid was red, swollen, and teary. The patient explains that these headaches have continued, and always seem to start after he wakes up at 5 p.m. (the time of this evaluation), approximately 3-4 times per week. When asked if lying down reduced the symptoms, the patient explained that laying down actually made the pain worse, so he is forced to pace around. However, when asked if his pain ever increases during an attack, the patient reports that the pain is often constant. In addition, the patient denies an increase in symptoms while staring at lights. The therapist asks if he ever feel nauseous, dizzy or confused. The patient denies any of these symptoms and believes these headaches are just “his body’s way of adjusting to the change in sleep patterns.”

- Past Medical History: CAD, DM, HTN

- Family History: CAD, DM

- Risk Factors: 1 pack/ day smoker, 1-2 Beer/ day

Objective Measurements[edit | edit source]

Vital Signs:

- Heart Rate: 88

- Blood Pressure: 122/ 80 (Controlled with Lisinopril)

- Respiratory Rate: 16

- Pain Scale: During attack 9/10

- Sensation: Intact

- Reflexes: Intact

AROM:

- Cervical Flexion: WNL

- Cervical Extension: WNL

- Cervical R/ L Rotation: WNL

- Cervical R/ L Sidebend: WNL

- Shoulder Flex/ ABD/ ER/ IR: WNL

MMT:

- Cervical Flexion/ Extension: 5/5

- Cervical ROT: 5/5

- Shoulder Flexion: 5/5

- Shoulder IR/ER: 5/5

- Shoulder ABD: 5/5

- Scapular Retractors: 4+/5

- Elbow Flexion/ Extension: 5/5

Palpation: No palpable tenderness along suboccipital, upper trapezius, or levator scapulae muscles.

Balance and Vestibular Assessments:

- Single Limb Stance Eyes Open: 36 seconds

- Single Limb Stance Eyes Closed: 20 seconds

- VOR x 1: Negative

- VOR x 2: Negative

- Saccades: Negative

- Smooth Pursuit: Negative

- Nystagmus: Negative.

- Visual Field Cut: Negative

Clinical Hypothesis[edit | edit source]

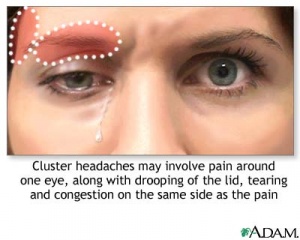

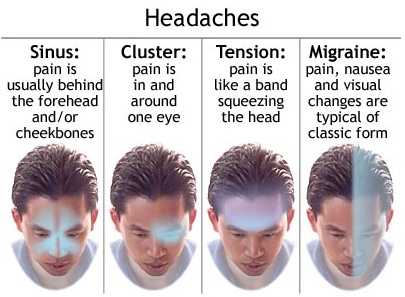

A patient’s severe headache with sudden onset would be very alarming as a therapist and definitely warrants addressing immediately and following up. The most likely diagnosis for the above patient would be a cluster headache. This diagnosis is relatively rare, however, the pain is typically described as sharp, pulsating, or pressure.[1] Cluster headaches are also typically suffered by males between the ages of 20-40.[2] Pain is commonly unilateral temporal or periorbital pain that lasts from 15 minutes to 3 hours and occurs with other autonomic symptoms. These descriptors match up to the patient’s reports and experience. Repeated occurrences of cluster headaches can occur in the same day and circadian patterns such as the repeated 5:00 occurrence is a common characteristic.[2],[1],[3] For this patient, the headache onset has been recent. However, assuming it is a true cluster headache, a seasonal pattern may later be observed with headaches occurring at similar times throughout the year.[3] The patient’s description of watery, red, and swollen eyes, is a typical finding with cluster headaches. These headaches are associated with a region innervated by the trigeminal nerve which causes ipsilateral autonomic reactions.[3]Common associated symptoms include ipsilateral conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinnorrhea, eyelid edema, forehead and facial swelling, miosis, and ptosis. Since the headache was rather sudden and severe, as a therapist we need to be concerned about when immediate referral may be necessary. The time to reach peak intensity is the primary determining factor in ruling out thunderclap headache which could be a dangerous form of headache that would require medical attention. It would be important to discuss this with the patient if he is able to verbalize the specific time and pain level of his current headache. A thunderclap headache reaches peak intensity in less than one minute.[4] A thunderclap headache may have associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, photosensitivity, neck involvement, and altered cognition.[4] However, the lack of these symptoms is not enough to definitively rule out thunderclap headache. Assuming the patient denies that the onset was within one minute to peak intensity and since his vital signs are normal, immediate referral may not be necessary in this case. I would want to refer the patient to his primary care physician for consultation considering the nature of the headaches and his history of CAD following this visit. Further testing or imaging may be warranted.

Factors to be aware of that may warrant immediate referral in patients complaining of headaches include:[1]

- a thunderclap headache with pain occurring suddenly and peaking within a few minutes

- history of HIV

- coexisting infection

- reports of experiencing the worst headache of their life in a patient >50 years old

- associated neurological findings

- an aura lasting greater than 60 minutes

- SBP >180 or DBP >120

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Multidisciplinary approach

- Neurologist

- ENT

- PT: May need to rule out more serious complications before initiating PT

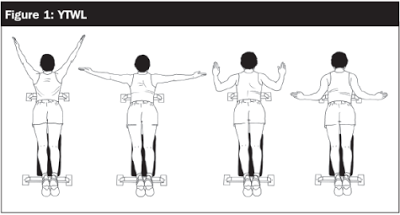

- Y's and T's

- Deep neck flexors

Manual Therapy

- Mobilizations to cervical spine [9]

Other

- General stretching to postural muscles (i.e. Upper Trap) [7]

- Heat [10]

- Ultrasound[10]

- TENS [10]

- Soft tissue/trigger point massage [6],[10]

- Balance and gait training with use of varying sensory inputs [7]

- Posture education [6],[7]

- Education on ergonomics at home and in the workplace [6]

Adjuncts to Physiotherapy

- Relaxation therapy [6],[7],[9]

- Biofeedback [6]

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (stress-management) [10]

- Acupuncture [10]

- Medications [6],[9]

Outcomes[edit | edit source]

With physical therapy improvement was made in the severity of the patient's symptoms. Patient was educated on his smoking and drinking habits as both of these have been shown to increase cluster headache symptoms. Patient began a medication regime[9] started by his doctor and also went through a conditioning program as aerobic exercise has also been shown to decrease cluster headache symptoms. By the end of treatment patient's pain went from 9/10 to 6/10 and he was discharged to continue the aerobic program and HEP.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

One half of the adult population worldwide is affected by a headache disorder[1]. As physical therapists, we will encounter patients who have multiple comorbidities, including headaches, which can impact their treatment plan. Since cluster headaches usually present suddenly with severe pain, immediate referral must be considered. Although physical therapists cannot directly treat cluster headaches, we must be aware of and be flexible with patient’s symptoms from the headache, and know when to refer them onto another medical professional. A knowledge base on what types of symptoms point to cluster headaches is important to have in order to help distinguish which symptoms fall within our scope of practice. We as physical therapists may be the first practitioners to pick up on specific details that indicate further medical intervention is needed. A multidisciplinary approach to treating cluster headaches is necessary to ensure optimal patient care for cluster headaches.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hainer BL, Matheson EM. Approach to Acute Headache in Adults. Am Fam Physcian. 2013 May; 87(10): 682-687.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weaver-Agostoni J. Cluster Headache. Am Fam Physician. 2013 July; 88(2): 122-128.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bhargava A, Pujar G, Banakar B, et al. Study of cluster headache: A hospital-based study. J Neurosciences In Rural Practice. 2014 October; 5(4): 369-373.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Schwedt, TJ. Thunderclap Headaches: A Focus on Etiology and Diagnostic Evaluation. J of Head and Face Pain. 2013 March.

- ↑ Types of Headaches Picture (House Call MD blog) {internet image}. 2011. Available from: http://www.myhousecallmd.com/headaches-why-wont-my-head-stop-pounding/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Biondi D. Physical Treatments for Headache: A Structured Review. Headache.2005 Jun;45(6):738-46.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Whitney S, Wrisley D, Brown K, Furman J. Physical Therapy for Migraine-Related Vestibulopathy and Vestibular Dysfunction with History of Migraine. Laryngoscope. 2000 Sept; 110(9): 1528-34.

- ↑ Posture Exercises (wordpress.com) {internet image}. 2014. Available from: https://smashingonline.wordpress.com/2014/02/06/5-exercises-to-improve-your-tennis-game/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Chaibi A, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB. Manual Therapies for Migraine: A Systematic Review. J Headache Pain. 2011 Apr;12(2):127-33.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Vernon H, McDermaid C S, Hagino C. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of complementary/alternative therapies in the treatment of tension-type and cervicogenic headache. PubMed [10581824]. 2002 Feb [cited 2015 Mar]. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/ShowRecord.asp?AccessionNumber=12000003174#.VQyOvEtgNuY.