Autogenic Drainage

Original Editor - The Open Physio project.

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Admin, Jarapla Srinivas Nayak, WikiSysop, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Shreya Pavaskar, Tony Lowe, Evan Thomas, Oyemi Sillo, Adam Vallely Farrell and Emily Mulligan

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Autogenic Drainage (AD), is an airway clearance technique that is characterized by breathing control, where the individual aims to adjust the rate, depth, and location of lung volumes during respiration[1]. AD is based on a series of physiological principles believed to enable the patient to achieve an independent airway clearance regimen that is adapted to their individual pathology and pulmonary function[2]. Autogenic drainage was developed in Belgium in the late 1960s by Chevaillier. During 1980's, it was utilized throughout Europe to treat asthmatic patients who had suffered retention of secretions in the chest and difficulty in clearing the secretions.[3]

The overall aim of AD is to reach the highest possible expiratory airflow in different generations of the bronchi simultaneously with an active, but not forced expiration. Secretions are systematically transported from peripheral to more central airways by breathing at lower lung volumes in the expiratory reserve volume (ERV), through progressively higher lung volumes in the inspiratory reserve volume (IRV)[5]. Chevaillier previously described these three phases as 'unstick', 'collect', and 'evacuate'. Nowadays, these phases are not seen as separate, rather that they blend into one another.

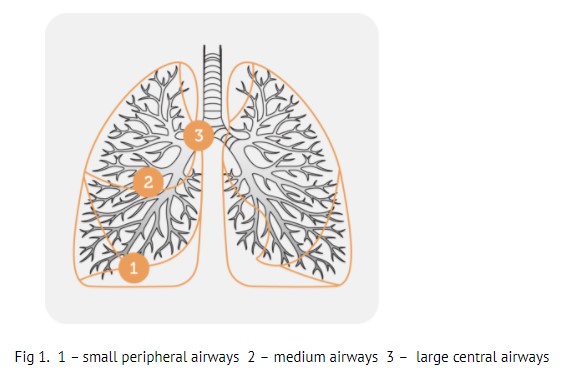

It uses breathing at different lung volumes to loosen, mobilize, and move secretions in three stages towards the larger central airways. (fig.1)

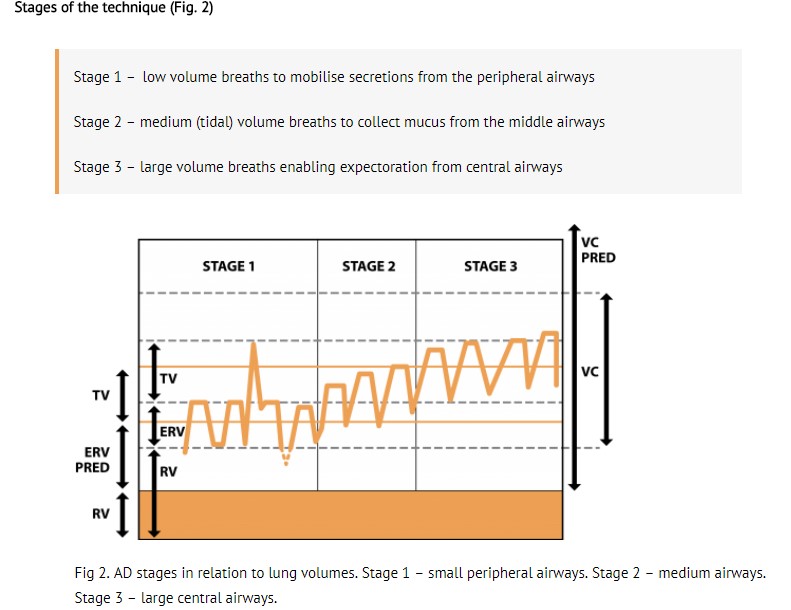

It consists of three stages:(fig.2)

Stage 1[edit | edit source]

Unstick secretions - breathe as much air out of your chest as you can then take a small breath in, using your tummy, feeling your breath at the bottom of your chest. You may hear secretions start to crackle. Resist any desire to cough.

Loosening peripheral secretions by breathing at low lung volumes (slow, deep air movement)

Repeat for at least 3 breaths.

Stage 2[edit | edit source]

Collect secretions - as the crackle of secretions starts to get louder, change to medium-sized breaths in, continue small breaths out. Feel the breaths more in the middle of your chest.

Repeat for at least 3 breaths.

Collecting secretions from central airways by breathing at low to middle lung volumes (slow, mid-range air movement)

Stage 3[edit | edit source]

Evacuate secretions - when the crackles are louder still, take long, slow, full breaths into your absolute maximum inspiration, continuing to take small breaths out.

Repeat for at least 3 breaths.

Expelling secretions from the central airways by breathing at mid to high lung volumes (shallow air movements)[6]

The velocity or force of the expiratory airflow must be adjusted at each level of inspiration so that the highest possible airflow is reached in that generation of bronchi, without being high enough to cause the airways to collapse during coughing. Autogenic drainage is performed whilst sitting upright and does not utilize Postural Drainage positions.

The Rationale behind the Autogenic Drainage Technique[edit | edit source]

The rationale for the technique is the generation of shearing forces induced by airflow. The speed of the expiratory flow may mobilize secretions by shearing them from the bronchial walls and transporting them from the peripheral to the central airways.

Procedure[edit | edit source]

Posture (Fig.3)

Choose a breath-stimulating position like sitting or reclining[7]. Relax, with the neck slightly extended.

- Clear your nose and throat by blowing your nose and huffing.

Breathing in - Slowly breathe in through the nose to keep the upper airways open. Use the diaphragm and/or the abdomen if possible.

- First, take a large breath in, hold it for a moment. Breathe all the way out for as long as you can. Now you are at low lung volume. See picture below. The size of breath and level at which you breathe depends on where the mucus is located.

- Take a small to normal breath in, and pause. Hold your breath for about 3 seconds. All the upper airways should be kept open. This improves the even filling of all lung parts. The pause allows time for the air to get behind the mucus.

Breathing out - Breathe out through the mouth. Keep the upper airways open. This is your glottis, throat, and mouth. Breathing out is done in a sighing manner. When you force your breath out the airways can collapse. You will hear a wheeze.

- At low lung level, breath using your abdominal muscles. Squeeze all the air out until you can breathe out no more.

- You hear the mucus rattling in the airways when breathing the right way. Put a hand on your upper chest, and feel the mucus vibrating. High frequencies mean that the mucus is in the small airways. Low frequencies mean that the mucus is in the large airways. Using this feedback lets you easily adjust the technique.

- Repeat the cycle. Inhale slowly to avoid sending the mucus back down. Keep breathing at a low level until the mucus collects and moves upward. Signs of this are:

- The crackling of the mucus can be heard as you exhale.

- You feel the mucus moving up.

- You feel a strong urge to cough.

- The level of breathing is raised when any of the above occurs. Refer to the picture below. Moving the breathing from lower to higher lung area takes the mucus with it.

- Finally, the collected mucus reaches the large airways where it can be cleared by a high lung volume huff. Don't cough until the mucus is in the larger airways. Cough only if a huff did not move the mucus to the mouth.

- You have now finished one cycle. Take a break of one to two minutes. Relax and perform breathing control before you start on the next cycle. The cycles are repeated during the session. A session lasts between twenty to forty-five minutes or until you feel all the mucus has been cleared. Do sessions of AD more often if you still have mucus present at the end of a session.

Length and Frequency of AD treatment sessions[edit | edit source]

The length of an AD session is dependent on the disease severity, knowledge of the technique, quantity of secretions etc.[7] The aim is to clear the most secretions possible by the end of the treatment so that previously obstructed areas of lung re-expand. The frequency of AD also depends upon the same factors as previously mentioned. The more secretions, the more times and/or sessions per day. [5]

Benefits of AD[edit | edit source]

- No equipment is required

- Patients can perform their airway clearance independently

- Less effort is be required to expectorate which reduces stress on the pelvic floor

Disadvantages of AD[edit | edit source]

- Patients generally need to be over 8 years old

- The technique can be difficult to teach

- Patients need the cognitive ability to understand the basic physiology behind the technique

- To benefit from the auditory feedback, patients need to have a moderate or large amount of sputum

Combining AD with other techniques[edit | edit source]

AD can also be performed in conjunction with other airway clearance devices and also positive pressure.

PEP: Traditionally AD has been combined with PEP via pursed lip breathing to assist the patient in balancing expiratory forces during AD, or flow modulation[2]. If increased levels of PEP are required to modulate flow, an oscillatory PEP device might be used e.g. PEP mask, Acapella, Flutter, or Cornet.[8]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Published studies of autogenic drainage are limited with the majority of trials being in the cystic fibrosis (CF) cohort. The physiological rationale lends support for the use of AD in non-CF bronchiectasis.

Most of the studies of AD compare its efficacy with other airway clearance[9][10]. However, all these studies have methodological problems, for example, small sample size or are of short treatment duration. The ACPCF standards of care outlined strong recommendations to consider autogenic drainage when choosing an airway clearance technique. There is some evidence to suggest that autogenic drainage is as effective as other airway clearance techniques.

Evidence suggests that flutter device should be more preferred than autogenic drainage in treatment of individuals with chronic bronchitis.[11]

In a long term study of patients with CF comparing AD with postural drainage and percussion, the patients expressed a marked preference for AD (Davidson et al 1992).

In a comparison with ACBT, postural drainage and manual techniques, AD was found to be equally effective in improving lung function in patients with COPD with copious secretions (Savci 2000).

Greater expectoration was achieved with AD compared to PEP therapy (Lindemann 1990).

The long term effects of AD on quality of life and lung function, compared to other airway clearance techniques, was similar[9].

There are no studies evaluating assisted AD (AAD) in the bronchiectasis population group. In the Cystic fibrosis population, studies have found no provocation of GOR has been associated with AAD, bouncing or the combination of both (Van Ginderdeuren 2001, 2003).

Resources[edit | edit source]

Paula Agostini and Nicola Knowles, Autogenic drainage: the technique, physiological basis and evidence, Physiotherapy, Volume 93, Issue 2, June 2007, Pages 157-163

Autogenic Drainage by Dr. Vinod Ravaliya, MPT

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ David A. Autogenic Drainage - the German approach. In: J. Pryor, editor. Respiratory Care, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chevaillier J. Autogenic Drainage. In: IPG/CF. Physiotherapy in the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. 2nd ed. IPG/CF; 1995

- ↑ Bronchiectasis Toolbox. Autogenic Drainage. Available from:http://bronchiectasis.com.au/physiotherapy/techniques/autogenic-drainage (Accessed 14 September 2020)

- ↑ Autogenic drainage. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_n0nuy8VWmI [Last accessed 19 Sept 2019]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chevaillier J. Autogenic Drainage. In: D. Lawson, editor . Cystic Fibrosis Horizons, Chichester: John Wiley; 1984: p235

- ↑ Boyd S, Brooks D, Agnew-Coughlin J, Ashwell J. Evaluation of the Literature on the Effectiveness of Physical Therapy Modalities in the Management of Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Paediatric Physical Therapy. 1994; 6(2):70-74.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Cheavaillier J. Autogenic Drainage. Unpublished course notes: De Haan; 1992.

- ↑ Davidson AGF, McIlwaine PM, Wong LTK, Nakielna EM, Pirie GE. Physiotherapy in Cystic Fibrosis, A Comparative Trial of Positive Expiratory Pressure, Autogenic Drainage and Conventional Percussion and Drainage Techniques. Pediatric Pulmonology, suppl. 132, 1988.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pryor JA, Tannenbaum E, Scott SF, Burgess J, Cramer D, Gyi K, Hodson ME. Beyond postural drainage and percussion: Airway clearance in people with cystic brosis. J Cystic Fibrosis 2010; 9:187-192.

- ↑ Lindemann H, Boldt A, Kieselmann R. Autogenic Drainage: ef cacy of a simpli ed method. Acta Univ Carol Med (Praha). 1990; 36(1-4):210-2.

- ↑ Patil DC, Sagar DJ. Comparison of Flutter and Autogenic Drainage on Airway Clearance In Patients with Moderate Chronic Bronchitis.(2020). Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res.;10(4):L60-63.