Ankle Osteochondral Lesions

Original Editors - Lore Aerts as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-Based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Allan D'Hose, Lore Aerts, Admin, Scott Cornish, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Wanda van Niekerk, Ward Willaert, WikiSysop, Pinar Kisacik, Ewa Jaraczewska, Maarten Cnudde and Cameron Mostinckx

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Symptomatic osteochondral ankle defects often require surgical treatment. An osteochondral ankle defect is a lesion of the talar cartilage and subchondral bone mostly caused by a single or multiple traumatic events, leading to partial or complete detachment of the fragment. The defects cause deep ankle pain associated with weightbearing. Impaired function, limited range of motion, stiffness, catching, locking and swelling may be present. These symptoms place the ability to walk, work and perform sports at risk.

Osteochondral lesions may also involve the talar dome, most frequently the medial aspect. It is relatively prevalent and are an important cause of ankle morbidity.[1] Osteochondral lesion of the talus (OLT) is a broad term used to describe an injury or abnormality of the talar articular cartilage and adjacent bone. Historically, a variety of terms have been used to refer to this clinical entity including osteochondritis dissecans, osteochondral fracture, and osteochondral defect. Currently, six characteristics are used to categorise a particular lesion. An OLT can be described as chondral (cartilage only), chondral-subchondral (cartilage and bone), subchondral (intact overlying cartilage), or cystic. Lesions can then be subdivided as stable or unstable and non-displaced or displaced. The stability of a lesion can be assessed directly with arthroscopy or indirectly with MRI using DeSmet’s criteria.[1]

A lesion can also be categorised by its location on the articular surface of the talus as medial, lateral, or central with added subdivisions into anterior, central, or posterior as advocated by some authors. An additional description of identifying whether the lesion is contained or not contained (shoulder) may also be included. Finally, although no accepted definition of lesion size exists, OLTs can generally be considered as either small or large based on their cross-sectional area or greatest diameter (area greater than or less than 1.5 cm² or diameter greater than or less than 15 mm).[2][3]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

As the foot is inverted on the leg, the lateral border of the talar dome is compressed against the face of the fibula (stage I), while the collateral ligament remains intact. Further inversion ruptures the lateral ligament and may cause avulsion at its attachment (stage II), which may become completely detached, but remain in place (stage III) or be displaced by further inversion (stage IV). With this excessive invertion force, the talus is rotated laterally within the mortis joint in the frontal plane, impacting and compressing the lateral talar margin against the articular surface of the fibula. A portion of the talar margin can be sheared off from the main body of the talus, causing lateral OLT.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

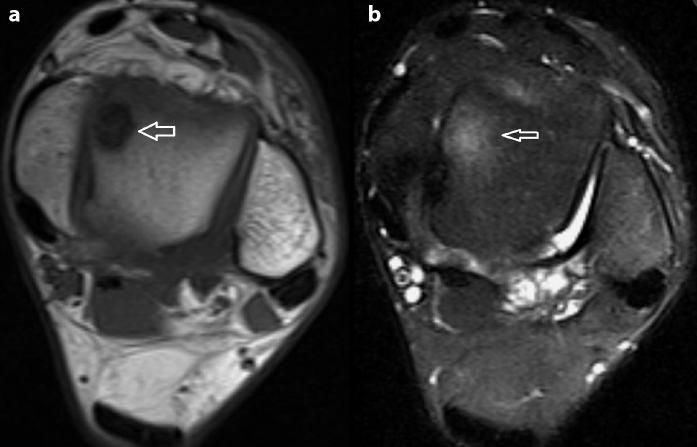

As the injury is intra-articular an MRI is required to diagnose the extent of the injury. On images it is easy to see the extent of damage to the surface of the cartilage. In the image, the ankle on the right indicates bone oedema. If only the cartilage is damaged it is termed chondral and if the cartilage and bone is involved then the diagnosis is a osteochondral lesion.[4][1] Younger people have a higher incidence of trauma history and the lesion size is usually larger as they are exposed to more diverse sporting activities.[5]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

An osteochondral lesion is rarely diagnosed via a physical exam without further testing. Other diagnoses sharing similar symptoms: [2][3]

- Loose bodies

- Synovitis

- Ligament injury

- Fracture or crack of the talus

- Cyst formation

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The location of the lesion, lesion size, containment, number of lesions, and combined intra-articular lesions can be identified through a preoperative MRI and are finally determined by arthroscopic surgery. Lesion size is a prognostic factor in osteochondral lesions of the talus and so may serve as a basis for preoperative surgical decisions. Size is measured by MRI and the cut off size for increased risk of clinical failure is approximately 150 mm².[4][6]

Outcome Measures[7][2][8][edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The results of a physical examination can vary as there is no specific test to diagnose an osteochondral lesion. The ankle may demonstrate acute injury with swelling and ecchymosis or it may appear completely normal, as is often the case with delayed presentations. Attempts to elicit tenderness with palpation should be made by focusing on the common sites of osteochondral lesions.

Posteromedial lesions: Tenderness may occur on palpating the ankle in dorsiflexion and the region posterior to the medial malleolus is palpated.[9]

Anterolateral lesions: Tenderness may occur when the ankle is palpated laterally with a plantar flexion.

These findings are nonspecific because the tenderness could likely be related to joint synovitis instead of an osteochondral lesion. Other tests should be performed to measure the range of motion for stiffness and to feel for the crepitus and signs of clicking or locking. Lateral ligamentous stability should also be examined.[8] Reduced ROM usually persists for 4-6 weeks after the acute event and walking on uneven ground may aggravate symptoms.

MRI is the gold standard for OCL diagnosis, providing information about bone bruise, cartilage status and soft tissues. X-ray and CT’s are also valuable, but rather to rule out fractures and for the detection of subchondral bone injuries.[4]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Non-surgical: Osteochondral lesions of the ankle can be treated with injections of Platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid, which results in a decrease in pain scores and an increase in function for at least 6 months. Platelet-rich plasma is significantly better than hyaluronic acid.[10] Stage 1,2 and 3 lesions are less likely to progress to arthritis and do well with non-operative management. A non-weight bearing cast is attached for 6 weeks and is then followed by a gradual return to weight bearing and athletic activity.[11]

Surgical: The preferred surgical treatment of talar osteochondral lesions is using a local osteochondral talar autograft. In this procedure an arthrotomy is performed through a 7 cm anteromedial or anterolateral incision.[12]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy treatment is vital for all patients with an osteochondral lesion of the talar dome to maximise the healing process, ensuring an optimal outcome and to reduce the likelihood of recurrence.

- soft tissue massage

- Electrotherapy (e.g. ultrasound)

- anti-inflammatory advice

- joint mobilisation

- ankle taping

- ankle bracing

- ice or heat treatment

- exercises to improve flexibility, strength and balance

- education

- activity modification advice

- crutches prescription

- the use of a protective boot

- biomechanical correction

- a gradual return to activity program

Several factors may also slow the healing process and increase the likelihood of a poor outcome in patients with this condition. These factors should be assessed and corrected by the treating physiotherapist and may include:

- poor foot mechanics

- joint stiffness

- poor flexibility

- inadequate strength

- poor balance

If there is no sign of improvements, further investigation is required. X-ray, CT scan, MRI or a review by a specialist who can advise on any procedures that may be appropriate to improve the condition. A review with a podiatrist may also be indicated for the prescription of orthotics and appropriate footwear advice.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Ankle osteochondral lesions are usually as a result of traumatic events and present as deep ankle pain, affecting gait and range of movement especially on weight wearing. Diagnosis and extent of the damage is confirmed by MRI, with younger people usually more at risk due to intensity of their sporting activities. MRI is also necessary to rule out differential diagnosis'. Management may be non surgical or surgical with follow up physiotherapy treatment essential for a return to normal activities and/or to sport.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Durur-Subasi I, Durur-Karakaya A, Yildirim OS. Osteochondral Lesions of Major Joints. Eurasian J Med. 2015 Jun;47(2):138-44.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 McGahan PJ, Pinney SJ. Current concept review: osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2010 Jan;31(1):90-101.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Assenmacher JA, Kelikian AS, Gottlob C, Kodros S. Arthroscopically assisted autologous osteochondral transplantation for osteochondral lesions of the talar dome: an MRI and clinical follow-up study. Foot Ankle Int. 2001 Jul;22(7):544-51.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Choi GW, Choi WJ, Youn HK, Park YJ, Lee JW. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: are there any differences between osteochondral and chondral types? Am J Sports Med. 2013 Mar;41(3):504-10.

- ↑ Park HW, Lee KB. Comparison of chondral versus osteochondral lesions of the talus after arthroscopic microfracture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015 Mar;23(3):860-7.

- ↑ Choi WJ, Park KK, Kim BS, Lee JW. Osteochondral lesion of the talus: is there a critical defect size for poor outcome? Am J Sports Med. 2009 Oct;37(10):1974-80.

- ↑ Shultz S, Olszewski A, Ramsey O, Schmitz M, Wyatt V, Cook C. A systematic review of outcome tools used to measure lower leg conditions. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Dec;8(6):838-48.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hale SA, Hertel J. Reliability and Sensitivity of the Foot and Ankle Disability Index in Subjects With Chronic Ankle Instability. J Athl Train. 2005 Mar;40(1):35-40.

- ↑ AANA Advanced Arthroscopy: the Foot and Ankle; 1st ed, Amendola N, Stone J; Saunders, July 2010, p.99

- ↑ Mei-Dan O, Carmont MR, Laver L, Mann G, Maffulli N, Nyska M. Platelet-rich plasma or hyaluronate in the management of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Mar;40(3):534-41.

- ↑ Clinical Sports Medicine: Medical management and Rehabilitation; Walter R. Frontera; p467 level of evidence : 2A

- ↑ Jung, HG, Foot and Ankle Disorders: An Illustrated Reference; 2016, Springer Berlin Heidelberg; p.129