Acromegaly

Original Editors - Alex Kent from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Alex Kent, Admin, Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, Chelsea Mclene, 127.0.0.1 and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

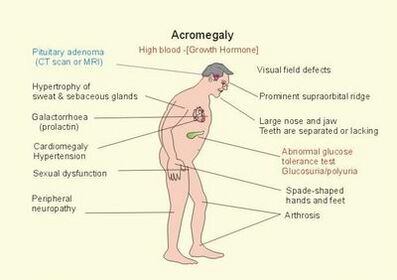

Acromegaly is the result of excessive human growth hormone production in skeletally mature patients, most commonly from a pituitary adenoma. This excess of growth hormone in individuals whose epiphyses have not fused results in gigantism (excessively tall stature).

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Acromegaly is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged adults and can result in extreme disfigurement, grave complicating conditions, and early death. It has an insidious onset, slow progression and may be difficult to diagnose in the early stages, only being diagnosed when the external features, especially those of the face, become noticeable.[1]

- The prevalence of acromegaly is approximately 40-70 cases per million persons. However, new research suggests that the prevalence may be as high as 77 cases per million persons.[2][3]

- The annual incidence of acromegaly is approximately is 3-4 new cases per million persons.[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Acromegaly affects many of the body's systems, and various signs and symptoms develop over a period of several years.[4] They range from subtle changes to notable disfigurement.[3] Common features are:[3][5][4][6]:

- Hyperhydrosis (increased perspiration) and acne.

- Increased skin thickness and darkening and thickening of body hair

- Frontal skull bossing- an abnormally heavy brow and prominent forehead, widening of the maxilla accompanied by separation of the teeth, jaw malocclusion and overbite.

- Soft tissue enlargement, joint pain

- Skeletal overgrowth and thickening causing many areas to appear swollen, hand and foot enlargement

- Deep and husky voice due to thickening of cartilage in the larynx

- Ventilatory dysfunction

- Weight gain

- Sleep apnea

- Vision problems

Markers[edit | edit source]

Typically cases show elevated levels of growth hormone and IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1)

Pathology[edit | edit source]

- Approximately 95% of cases are the result of a pituitary adenoma. The remaining

- 5% of cases are the result of other tumors of the pancreas, lungs, or adrenal glands that release growth hormone.

- A few number of cases result from the excessive use of exogenous growth hormone in athletes.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

The treatment of choice is resection of the secreting adenoma.

- Radiation therapy is also used in medical circumstances where other therapies have not been able to control tumor size, growth and production of excess growth hormone.

- The severity of symptoms and comorbidities for acromegaly patients is relates directly to the level of elevated hormone as well as how long the patient was exposed to a high level of HGH.

- Mortality rates are returned to those of the general population if appropriate diagnosis and treatment are achieved to normalize serum growth hormone and IGF-1 levels.[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Acromegaly is a disease which affects several systems in the body.[7][3][6] Therapists may be called on to provide a program addressing the musculoskeletal and neurological manifestations of the disease. [8]

Preferred Practice Patterns:[8]

- 4D: Impaired joint mobility, motor function, muscle performance, and range of motion associated with connective tissue dysfunction.[8]

- 4E: Impaired joint mobility, motor function, muscle performance, and range of motion associated with localized inflammation.[8]

- 4F: Impaired joint mobility, motor function, muscle performance, range of motion, and reflex integrity associated with spinal disorders.[8]

- 5F: Impaired peripheral nerve integrity and muscle performance associated with peripheral nerve injury.[8]

Screening[edit | edit source]

- Individuals with acromegaly should be screened for changes in joint mobility, decreased exercise tolerance, and weakness.[8]

- If an acromegalic client presents to physical therapy with unusual muscle weakness, they should be referred to a physician for a complete workup to look for neuropathies and inflammatory myopathies. This will help identify underlying causes which can be treated.[8]

Orthopedic Intervention[edit | edit source]

- Arthritis of several joints is often present in patients with acromegaly.[8] In addition, carpal tunnel syndrome is seen in approximately 50% of patients with acromegaly, and there is a similar incidence of thoracic and lumbar pain in acromegalic patients.[8]

- X-ray studies have demonstrated large osteophytes in the anterior longitudinal ligament and increased intervertebral space.[8]

- A physical therapy program would work to promote muscle strength, mobility of the joints, and independence with functional activities.[8] Adaptive equipment for assistance with activities of daily living may be considered depending on the severity of the disease.[8]

Postoperative Intervention[edit | edit source]

- Exercise and ambulation are encouraged within the first 24 hours after removal of the pituitary tumor.[8]

- Breathing exercises are indicated. However, coughing, sneezing, and blowing the nose are contraindicated.[8]

- Monitor vital signs closely. Any change in vision, dropping pulse rate, or rising blood pressure could indicate an increase in intracranial pressure and should be reported immediately.[8]

- The physical therapist should consult with the nursing staff to determine if blood glucose monitoring is needed during exercise. GH levels may drop rapidly after removal of the tumor and result in hypoglycemia.[8]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Several of the comorbidities of acromegaly overlap common disorders; as a result, the acromegaly may be misdiagnosed.[4] The comorbidities which may lead to improper diagnosis include:

- Arthritis[4]

- Hypertension[4]

- Diabetes mellitus[4][6]

- Carpal tunnel syndrome[4]

- Respiratory dysfunction[9]

- Cardiac involvement[9]

- Failure to suppress growth hormone can also be seen in patients with diabetes, renal failure, hepatic failure, and patients with obesity or those on estrogen replacement.[6] This could potentially lead to misdiagnosis.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radiopedia Acromegaly Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/acromegaly (accessed 18.8.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fleseriu M, Delashaw JB, Cook DM. Acromegaly: a review of current medical therapy and new drugs on the horizon. Neurosurg Focus 2010;29(4):E15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cordero RA, Barkan AL. Current diagnosis of acromegaly. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2008;9:13-19.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Reid TJ, Post KD, Bruce JN, Kanibir MN, Reyes-Vidal CM, Freda PU. Features at diagnosis of 324 patients with acromegaly did not change from 1981 to 2006: acromegaly remains under-recognized and under-diagnosed. Clinical Endocrinology 2010;72:203-208.

- ↑ Merck Manual Home Edition. Acromegaly and gigantism: pituitary gland disorders. (last accessed 10/2/2022).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Melmed S. Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J. Clin. Invest 2009;119:3189-3202.

- ↑ Vance M. Acromegaly: a fascinating pituitary disorder. Neurosurg Focus 2010;29(4):1.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 3rd ed. St.Louis: Saunders-Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Colao A, Ferone D, Marzullo P, Lombardi G. Systemic complications of acromegaly: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management. Endocrine Reviews. 2004; 25(1):102-152